Crystallography

Crystallography is the experimental science of determining the arrangement of atoms in crystalline solids (see crystal structure). The word "crystallography" is derived from the Greek words crystallon "cold drop, frozen drop", with its meaning extending to all solids with some degree of transparency, and graphein "to write". In July 2012, the United Nations recognised the importance of the science of crystallography by proclaiming that 2014 would be the International Year of Crystallography.[1]

Before the development of X-ray diffraction crystallography (see below), the study of crystals was based on physical measurements of their geometry using a goniometer.[2] This involved measuring the angles of crystal faces relative to each other and to theoretical reference axes (crystallographic axes), and establishing the symmetry of the crystal in question. The position in 3D space of each crystal face is plotted on a stereographic net such as a Wulff net or Lambert net. The pole to each face is plotted on the net. Each point is labelled with its Miller index. The final plot allows the symmetry of the crystal to be established.

Crystallographic methods now depend on analysis of the diffraction patterns of a sample targeted by a beam of some type. X-rays are most commonly used; other beams used include electrons or neutrons. Crystallographers often explicitly state the type of beam used, as in the terms X-ray crystallography, neutron diffraction and electron diffraction. These three types of radiation interact with the specimen in different ways.

- X-rays interact with the spatial distribution of electrons in the sample.

- Electrons are charged particles and therefore interact with the total charge distribution of both the atomic nuclei and the electrons of the sample.

- Neutrons are scattered by the atomic nuclei through the strong nuclear forces, but in addition, the magnetic moment of neutrons is non-zero. They are therefore also scattered by magnetic fields. When neutrons are scattered from hydrogen-containing materials, they produce diffraction patterns with high noise levels. However, the material can sometimes be treated to substitute deuterium for hydrogen.

Because of these different forms of interaction, the three types of radiation are suitable for different crystallographic studies.

Theory

| Condensed matter physics |

|---|

|

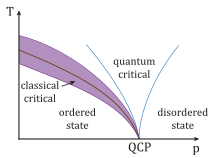

| Phases · Phase transition · QCP |

|

Solid · Liquid · Gas · Bose–Einstein condensate · Bose gas · Fermionic condensate · Fermi gas · Fermi liquid · Supersolid · Superfluidity · Luttinger liquid · Time crystal |

|

Phase phenomena |

|

Electronic phases Electronic band structure · Plasma · Insulator · Mott insulator · Semiconductor · Semimetal · Conductor · Superconductor · Thermoelectric · Piezoelectric · Ferroelectric · Topological insulator · Spin gapless semiconductor |

|

Electronic phenomena |

|

Magnetic phases Diamagnet · Superdiamagnet Paramagnet · Superparamagnet Ferromagnet · Antiferromagnet Metamagnet · Spin glass |

|

|

|

Soft matter |

|

Scientists Van der Waals · Onnes · von Laue · Bragg · Debye · Bloch · Onsager · Mott · Peierls · Landau · Luttinger · Anderson · Van Vleck · Mott · Hubbard · Shockley · Bardeen · Cooper · Schrieffer · Josephson · Louis Néel · Esaki · Giaever · Kohn · Kadanoff · Fisher · Wilson · von Klitzing · Binnig · Rohrer · Bednorz · Müller · Laughlin · Störmer · Yang · Tsui · Abrikosov · Ginzburg · Leggett |

With conventional imaging technique such as optical microscopy, obtaining an image of a small object requires collecting light with a magnifying lens. However, the resolution of any optical system is limited by the diffraction-limit of light, which depends on its wavelength. For example, visible light has a wavelength of about 4000 to 7000 ångström, which is three orders of magnitude longer than the length of typical atomic bonds and atoms themselves (about 1 to 2 Å). Therefore, a conventional optical microscope cannot resolve the spatial arrangement of atoms in a crystal. To do so, we would need radiation with much shorter wavelengths, such as X-ray or neutron beams.

Unfortunately, focusing X-rays with conventional optical lens can be a challenge. Scientists have had some success focusing X-rays with microscopic Fresnel zone plates made from gold, and by critical-angle reflection inside long tapered capillaries.[3] Diffracted X-ray or neutron beams cannot be focused to produce images, so the sample structure must be reconstructed from the diffraction pattern.

Diffraction pattern arises from the constructive interference of photons, scattered by the periodic, repeating feature of the sample under studies. Because of their highly ordered and repetitive atomic structure (Bravais lattice), crystals diffracts x-rays in a coherent manner, also referred as Bragg's reflection.

Notation

- Coordinates in square brackets such as [100] denote a direction vector (in real space).

- Coordinates in angle brackets or chevrons such as <100> denote a family of directions which are related by symmetry operations. In the cubic crystal system for example, <100> would mean [100], [010], [001] or the negative of any of those directions.

- Miller indices in parentheses such as (100) denote a plane of the crystal structure, and regular repetitions of that plane with a particular spacing. In the cubic system, the normal to the (hkl) plane is the direction [hkl], but in lower-symmetry cases, the normal to (hkl) is not parallel to [hkl].

- Indices in curly brackets or braces such as {100} denote a family of planes and their normals. In cubic materials the symmetry makes them equivalent, just as the way angle brackets denote a family of directions. In non-cubic materials, <hkl> is not necessarily perpendicular to {hkl}.

Techniques

Some materials that have been analyzed crystallographically, such as proteins, do not occur naturally as crystals. Typically, such molecules are placed in solution and allowed to slowly crystallize through vapor diffusion. A drop of solution containing the molecule, buffer, and precipitants is sealed in a container with a reservoir containing a hygroscopic solution. Water in the drop diffuses to the reservoir, slowly increasing the concentration and allowing a crystal to form. If the concentration were to rise more quickly, the molecule would simply precipitate out of solution, resulting in disorderly granules rather than an orderly and hence usable crystal.

Once a crystal is obtained, data can be collected using a beam of radiation. Although many universities that engage in crystallographic research have their own X-ray producing equipment, synchrotrons are often used as X-ray sources, because of the purer and more complete patterns such sources can generate. Synchrotron sources also have a much higher intensity of X-ray beams, so data collection takes a fraction of the time normally necessary at weaker sources. Complementary neutron crystallography techniques are used to identify the positions of hydrogen atoms, since X-rays only interact very weakly with light elements such as hydrogen.

Producing an image from a diffraction pattern requires sophisticated mathematics and often an iterative process of modelling and refinement. In this process, the mathematically predicted diffraction patterns of an hypothesized or "model" structure are compared to the actual pattern generated by the crystalline sample. Ideally, researchers make several initial guesses, which through refinement all converge on the same answer. Models are refined until their predicted patterns match to as great a degree as can be achieved without radical revision of the model. This is a painstaking process, made much easier today by computers.

The mathematical methods for the analysis of diffraction data only apply to patterns, which in turn result only when waves diffract from orderly arrays. Hence crystallography applies for the most part only to crystals, or to molecules which can be coaxed to crystallize for the sake of measurement. In spite of this, a certain amount of molecular information can be deduced from patterns that are generated by fibers and powders, which while not as perfect as a solid crystal, may exhibit a degree of order. This level of order can be sufficient to deduce the structure of simple molecules, or to determine the coarse features of more complicated molecules. For example, the double-helical structure of DNA was deduced from an X-ray diffraction pattern that had been generated by a fibrous sample.

Materials science

Crystallography is used by materials scientists to characterize different materials. In single crystals, the effects of the crystalline arrangement of atoms is often easy to see macroscopically, because the natural shapes of crystals reflect the atomic structure. In addition, physical properties are often controlled by crystalline defects. The understanding of crystal structures is an important prerequisite for understanding crystallographic defects. Mostly, materials do not occur as a single crystal, but in poly-crystalline form (i.e., as an aggregate of small crystals with different orientations). Because of this, the powder diffraction method, which takes diffraction patterns of polycrystalline samples with a large number of crystals, plays an important role in structural determination.

Other physical properties are also linked to crystallography. For example, the minerals in clay form small, flat, platelike structures. Clay can be easily deformed because the platelike particles can slip along each other in the plane of the plates, yet remain strongly connected in the direction perpendicular to the plates. Such mechanisms can be studied by crystallographic texture measurements.

In another example, iron transforms from a body-centered cubic (bcc) structure to a face-centered cubic (fcc) structure called austenite when it is heated. The fcc structure is a close-packed structure unlike the bcc structure; thus the volume of the iron decreases when this transformation occurs.

Crystallography is useful in phase identification. When manufacturing or using a material, it is generally desirable to know what compounds and what phases are present in the material, as their composition, structure and proportions will influence the material's properties. Each phase has a characteristic arrangement of atoms. X-ray or neutron diffraction can be used to identify which patterns are present in the material, and thus which compounds are present. Crystallography covers the enumeration of the symmetry patterns which can be formed by atoms in a crystal and for this reason is related to group theory and geometry.

Biology

X-ray crystallography is the primary method for determining the molecular conformations of biological macromolecules, particularly protein and nucleic acids such as DNA and RNA. In fact, the double-helical structure of DNA was deduced from crystallographic data. The first crystal structure of a macromolecule was solved in 1958, a three-dimensional model of the myoglobin molecule obtained by X-ray analysis.[4] The Protein Data Bank (PDB) is a freely accessible repository for the structures of proteins and other biological macromolecules. Computer programs such as RasMol, Pymol or VMD can be used to visualize biological molecular structures. Neutron crystallography is often used to help refine structures obtained by X-ray methods or to solve a specific bond; the methods are often viewed as complementary, as X-rays are sensitive to electron positions and scatter most strongly off heavy atoms, while neutrons are sensitive to nucleus positions and scatter strongly even off many light isotopes, including hydrogen and deuterium. Electron crystallography has been used to determine some protein structures, most notably membrane proteins and viral capsids.

Reference literature

The International Tables for Crystallography[5] is an eight-book series that outlines the standard notations for formatting, describing and testing crystals. The series contains books that covers analysis methods and the mathematical procedures for determining organic structure though x-ray crystallography, electron diffraction, and neutron diffraction. The International tables are focused on procedures, techniques and descriptions and do not list the physical properties of individual crystals themselves. Each book is about 1000 pages and the titles of the books are:

- Vol A - Space Group Symmetry,

- Vol A1 - Symmetry Relations Between Space Groups,

- Vol B - Reciprocal Space,

- Vol C - Mathematical, Physical, and Chemical Tables,

- Vol D - Physical Properties of Crystals,

- Vol E - Subperiodic Groups,

- Vol F - Crystallography of Biological Macromolecues, and

- Vol G - Definition and Exchange of Crystallographic Data.

Scientists of note

- William Astbury

- William Barlow

- C. Arnold Beevers

- John Desmond Bernal

- William Henry Bragg

- William Lawrence Bragg

- Auguste Bravais

- Glenn H. Brown

- Martin Julian Buerger

- Francis Crick

- Pierre Curie

- Peter Debye

- Johann Deisenhofer

- Boris Delone

- Gautam R. Desiraju

- Jack Dunitz

- David Eisenberg

- Paul Peter Ewald

- Evgraf Stepanovich Fedorov

- Rosalind Franklin

- Georges Friedel

- Paul Heinrich von Groth

- René Just Haüy

- Wayne Hendrickson

- Carl Hermann

- Johann Friedrich Christian Hessel

- Dorothy Crowfoot Hodgkin

- Judith Howard

- Robert Huber

- Isabella Karle

- Jerome Karle

- Aaron Klug

- Max von Laue

- Otto Lehmann

- Michael Levitt

- Henry Lipson

- Kathleen Lonsdale

- Ernest-François Mallard

- Charles-Victor Mauguin

- William Hallowes Miller

- Friedrich Mohs

- Paul Niggli

- Louis Pasteur

- Arthur Lindo Patterson

- Max Perutz

- Friedrich Reinitzer

- Hugo Rietveld

- Jean-Baptiste L. Romé de l'Isle

- Michael Rossmann

- Paul Scherrer

- Arthur Moritz Schönflies

- Dan Shechtman

- George M. Sheldrick

- Tej P. Singh

- Nicolas Steno

- Constance Tipper

- Daniel Vorländer

- Christian Samuel Weiss

- Don Craig Wiley

- Ralph Walter Graystone Wyckoff

- Ada Yonath

See also

- Abnormal grain growth

- Atomic packing factor

- Beevers–Lipson strip

- Condensed matter physics

- Crystal engineering

- Crystal growth

- Crystal optics

- Crystal structure

- Crystallite

- Crystallization processes

- Crystallographic database

- Crystallographic point group

- Crystallographic group

- Dynamical theory of diffraction

- Electron crystallography

- Euclidean plane isometry

- Fixed points of isometry groups in Euclidean space

- Fractional coordinates

- Group action

- International Year of Crystallography

- Laser-heated pedestal growth

- Materials science

- Metallurgy

- Mineralogy

- Modeling of polymer crystals

- Neutron crystallography

- Neutron diffraction at OPAL

- Neutron diffraction at the ILL

- NMR crystallography

- Permutation group

- Point group

- Precession electron diffraction

- Quantum mineralogy

- Quasicrystal

- Solid state chemistry

- Space group

- Symmetric group

- X-ray crystallography

- Lattice constant

References

- UN announcement "International Year of Crystallography". iycr2014.org. 12 July 2012

- "The Evolution of the Goniometer". Nature. 95 (2386): 564–565. 1915-07-01. doi:10.1038/095564a0. ISSN 1476-4687.

- Snigirev, A. (2007). "Two-step hard X-ray focusing combining Fresnel zone plate and single-bounce ellipsoidal capillary". Journal of Synchrotron Radiation. 14 (Pt 4): 326–330. doi:10.1107/S0909049507025174. PMID 17587657.

- Kendrew, J. C.; Bodo, G.; Dintzis, H. M.; Parrish, R. G.; Wyckoff, H.; Phillips, D. C. (1958). "A Three-Dimensional Model of the Myoglobin Molecule Obtained by X-Ray Analysis". Nature. 181 (4610): 662–6. Bibcode:1958Natur.181..662K. doi:10.1038/181662a0. PMID 13517261.

- Prince, E. (2006). International Tables for Crystallography Vol. C: Mathematical, Physical and Chemical Tables. Wiley. ISBN 978-1-4020-4969-9.

External links

- American Crystallographic Association

- Learning Crystallography

- Crystal Lattice Structures

- 100 Years of Crystallography Royal Institution animation

- Vega Science Trust Interviews on Crystallography Freeview video interviews with Max Perutz, Rober Huber and Aaron Klug.

- Commission on Crystallographic Teaching, Pamphlets

- Ames Laboratory, US DOE Crystallography Research Resources

- International Union of Crystallography

- Web Portal of Open Access Crystallography Resources

- Interactive Crystallography Timeline from the Royal Institution

- Nature Milestones in Crystallography

- Crystallography in the 21st century (editorial in Acta Crystallographica Section A)

- Crystallography on In Our Time at the BBC