Coronavirus disease 2019

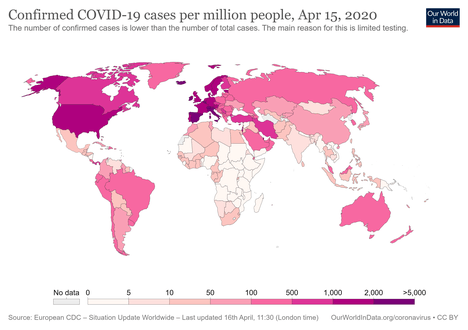

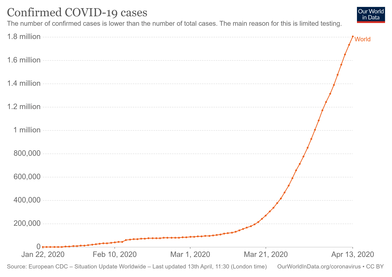

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is an infectious disease caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2).[8] The disease was first identified in December 2019 in Wuhan, the capital of China's Hubei province, and has since spread globally, resulting in the ongoing 2019–20 coronavirus pandemic.[9][10] As of 25 April 2020, more than 2.89 million cases have been reported across 185 countries and territories, resulting in more than 202,000 deaths. More than 815,000 people have recovered.[7]

| Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) | |

|---|---|

| Other names | |

| |

| Symptoms of COVID-19 | |

| Pronunciation |

|

| Specialty | Infectious disease |

| Symptoms | Fever, cough, shortness of breath, loss of smell, none[4][5][6] |

| Complications | Pneumonia, viral sepsis, acute respiratory distress syndrome, kidney failure. |

| Usual onset | 2–14 days (typically 5) from infection |

| Causes | Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) |

| Risk factors | Travel, viral exposure |

| Diagnostic method | rRT-PCR testing, CT scan |

| Prevention | Hand washing, face coverings, quarantine, social distancing |

| Treatment | Symptomatic and supportive |

| Frequency | 2,892,508[7] confirmed cases |

| Deaths | 202,455 (7.0% of confirmed cases)[7] |

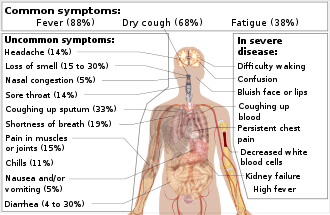

Common symptoms include fever, cough, fatigue, shortness of breath and loss of smell.[5][11][12] While the majority of cases result in mild symptoms, some progress to viral pneumonia, multi-organ failure, or cytokine storm.[13][9][14] More concerning symptoms include difficulty breathing, persistent chest pain, confusion, difficulty waking, and bluish skin.[5] The time from exposure to onset of symptoms is typically around five days but may range from two to fourteen days.[5][15]

The virus is primarily spread between people during close contact,[lower-alpha 1] often via small droplets produced by coughing,[lower-alpha 2] sneezing, or talking.[6][16][18] The droplets usually fall to the ground or onto surfaces rather than remaining in the air over long distances.[6][19][20] People may also become infected by touching a contaminated surface and then touching their face.[6][16] In experimental settings, the virus may survive on surfaces for up to 72 hours.[21][22][23] It is most contagious during the first three days after the onset of symptoms, although spread may be possible before symptoms appear and in later stages of the disease.[24] The standard method of diagnosis is by real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (rRT-PCR) from a nasopharyngeal swab.[25] Chest CT imaging may also be helpful for diagnosis in individuals where there is a high suspicion of infection based on symptoms and risk factors; however, guidelines do not recommend using it for routine screening.[26][27]

Recommended measures to prevent infection include frequent hand washing, maintaining physical distance from others (especially from those with symptoms), covering coughs, and keeping unwashed hands away from the face.[28][29] In addition, the use of a face covering is recommended for those who suspect they have the virus and their caregivers.[30][31] Recommendations for face covering use by the general public vary, with some authorities recommending against their use, some recommending their use, and others requiring their use.[32][31][33] Currently, there is not enough evidence for or against the use of masks (medical or other) in healthy individuals in the wider community.[6] Also masks purchased by the public may impact availability for health care providers.

Currently, there is no vaccine or specific antiviral treatment for COVID-19.[6] Management involves the treatment of symptoms, supportive care, isolation, and experimental measures.[34] The World Health Organization (WHO) declared the 2019–20 coronavirus outbreak a Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC)[35][36] on 30 January 2020 and a pandemic on 11 March 2020.[10] Local transmission of the disease has occurred in most countries across all six WHO regions.[37]

Signs and symptoms

| Symptom[4] | Range |

|---|---|

| Fever | 83–99% |

| Cough | 59–82% |

| Loss of Appetite | 40–84% |

| Fatigue | 44–70% |

| Shortness of breath | 31–40% |

| Coughing up sputum | 28–33% |

| Loss of smell | 15[38] to 30%[12][39] |

| Muscle aches and pains | 11–35% |

Fever is the most common symptom, although some older people and those with other health problems experience fever later in the disease.[4][40] In one study, 44% of people had fever when they presented to the hospital, while 89% went on to develop fever at some point during their hospitalization.[4][41]

Other common symptoms include cough, loss of appetite, fatigue, shortness of breath, sputum production, and muscle and joint pains.[4][5][42][43] Symptoms such as nausea, vomiting and diarrhoea have been observed in varying percentages.[44][45][46] Less common symptoms include sneezing, runny nose, or sore throat.[47]

More serious symptoms include difficulty breathing, persistent chest pain or pressure, confusion, difficulty waking, and bluish face or lips. Immediate medical attention is advised if these symptoms are present.[5][48]

In some, the disease may progress to pneumonia, multi-organ failure, and death.[9][14] In those who develop severe symptoms, time from symptom onset to needing mechanical ventilation is typically eight days.[4] Some cases in China initially presented with only chest tightness and palpitations.[49]

Loss of smell was identified as a common symptom of COVID‑19 in March 2020,[12][39] although perhaps not as common as initially reported.[38] A decreased sense of smell and/or disturbances in taste have also been reported.[50] Estimates for loss of smell range from 15%[38] to 30%.[12][39]

As is common with infections, there is a delay between the moment a person is first infected and the time he or she develops symptoms. This is called the incubation period. The incubation period for COVID‑19 is typically five to six days but may range from two to 14 days,[51][52] although 97.5% of people who develop symptoms will do so within 11.5 days of infection.[53]

A minority of cases do not develop noticeable symptoms at any point in time.[54][55] These asymptomatic carriers tend not to get tested, and their role in transmission is not yet fully known.[56][57] However, preliminary evidence suggests they may contribute to the spread of the disease.[58][59] In March 2020, the Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (KCDC) reported that 20% of confirmed cases remained asymptomatic during their hospital stay.[59][60]

Cause

Transmission

Some details about how the disease is spread are still being determined.[16][18] The WHO and the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) say it is primarily spread during close contact and by small droplets produced when people cough, sneeze or talk;[6][16] with close contact being within approximately 1–2 m (3–7 ft).[6][61] Both sputum and saliva can carry large viral loads.[62] Loud talking releases more droplets than normal talking.[63] A study in Singapore found that an uncovered cough can lead to droplets travelling up to 4.5 metres (15 feet).[64] An article published in March 2020 argued that advice on droplet distance might be based on 1930s research which ignored the effects of warm moist exhaled air surrounding the droplets and that an uncovered cough or sneeze can travel up to 8.2 metres (27 feet).[17]

Respiratory droplets may also be transmitted while exhaling, and speaking. Though the virus is not generally airborne,[6][65] the National Academy of Sciences has suggested that bioaerosol transmission may be possible.[66] In one study cited, air collectors positioned in the hallway outside of people's rooms yielded samples positive for viral RNA but finding infectious virus has proven elusive.[66] The droplets can land in the mouths or noses of people who are nearby or possibly be inhaled into the lungs.[16] Some medical procedures such as intubation and cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) may cause respiratory secretions to be aerosolised and thus result in an airborne spread.[65] Initial studies suggested a doubling time of the number of infected persons of 6–7 days and a basic reproduction number (R0 ) of 2.2–2.7, but a study published on April 7, 2020, calculated a much higher median R0 value of 5.7 for the epidemic in Wuhan.[67]

It may also spread when one touches a contaminated surface, known as fomite transmission, and then touches one's eyes, nose or mouth.[6] While there are concerns it may spread via faeces, this risk is believed to be low.[6][16]

Studies indicate that a significant portion of individuals with coronavirus lack symptoms (are asymptomatic) and that even those who eventually develop symptoms (are pre-symptomatic) can transmit the virus to others before showing symptoms. This means that the virus can spread between people even if those people are not exhibiting symptoms.[68][69][70] The European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC) says while it is not entirely clear how easily the disease spreads, one person generally infects two or three others.[18]

The virus survives for hours to days on surfaces.[6][18] Specifically, the virus was found to be detectable for one day on cardboard, for up to three days on plastic (polypropylene) and stainless steel (AISI 304), and for up to four hours on 99% copper.[21][23] This, however, varies depending on the humidity and temperature.[71][72] Surfaces may be decontaminated with many solutions (with one minute of exposure to the product achieving a 4 or more log reduction (99.99% reduction)), including 78–95% ethanol (alcohol used in spirits), 70–100% 2-propanol (isopropyl alcohol), the combination of 45% 2-propanol with 30% 1-propanol, 0.21% sodium hypochlorite (bleach), 0.5% hydrogen peroxide, or 0.23–7.5% povidone-iodine. Soap and detergent are also effective if correctly used; soap products degrade the virus' fatty protective layer, deactivating it, as well as freeing them from the skin and other surfaces.[73] Other solutions, such as benzalkonium chloride and chlorhexidine gluconate (a surgical disinfectant), are less effective.[74]

In a Hong Kong study, saliva samples were taken a median of two days after the start of hospitalization. In five of six patients, the first sample showed the highest viral load, and the sixth patient showed the highest viral load on the second day tested.[62]

Virology

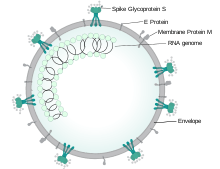

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) is a novel severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus, first isolated from three people with pneumonia connected to the cluster of acute respiratory illness cases in Wuhan.[75] All features of the novel SARS-CoV-2 virus occur in related coronaviruses in nature.[76] Outside the human body, the virus is killed by household soap, which bursts its protective bubble.[26]

SARS-CoV-2 is closely related to the original SARS-CoV.[77] It is thought to have a zoonotic origin. Genetic analysis has revealed that the coronavirus genetically clusters with the genus Betacoronavirus, in subgenus Sarbecovirus (lineage B) together with two bat-derived strains. It is 96% identical at the whole genome level to other bat coronavirus samples (BatCov RaTG13).[47] In February 2020, Chinese researchers found that there is only one amino acid difference in the binding domain of the S protein between the coronaviruses from pangolins and those from humans; however, whole-genome comparison to date found that at most 92% of genetic material was shared between pangolin coronavirus and SARS-CoV-2, which is insufficient to prove pangolins to be the intermediate host.[78]

Pathophysiology

The lungs are the organs most affected by COVID‑19 because the virus accesses host cells via the enzyme angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2), which is most abundant in type II alveolar cells of the lungs. The virus uses a special surface glycoprotein called a "spike" (peplomer) to connect to ACE2 and enter the host cell.[79] The density of ACE2 in each tissue correlates with the severity of the disease in that tissue and some have suggested that decreasing ACE2 activity might be protective,[80][81] though another view is that increasing ACE2 using angiotensin II receptor blocker medications could be protective and these hypotheses need to be tested.[82] As the alveolar disease progresses, respiratory failure might develop and death may follow.[81]

The virus also affects gastrointestinal organs as ACE2 is abundantly expressed in the glandular cells of gastric, duodenal and rectal epithelium[83] as well as endothelial cells and enterocytes of the small intestine.[84]

ACE2 is present in the brain, and there is growing evidence of neurological manifestations in people with COVID‑19. It is not certain if the virus can directly infect the brain by crossing the barriers that separate the circulation of the brain and the general circulation. Other coronaviruses are able to infect the brain via a synaptic route to the respiratory centre in the medulla, through mechanoreceptors like pulmonary stretch receptors and chemoreceptors (primarily central chemoreceptors) within the lungs. It is possible that dysfunction within the respiratory centre further worsens the ARDS seen in COVID‑19 patients. Common neurological presentations include a loss of smell, headaches, nausea, and vomiting. Encephalopathy has been noted to occur in some patients (and confirmed with imaging), with some reports of detection of the virus after cerebrospinal fluid assays although the presence of oligoclonal bands seems to be a common denominator in these patients.[85]

The virus can cause acute myocardial injury and chronic damage to the cardiovascular system.[86] An acute cardiac injury was found in 12% of infected people admitted to the hospital in Wuhan, China,[87] and is more frequent in severe disease.[88] Rates of cardiovascular symptoms are high, owing to the systemic inflammatory response and immune system disorders during disease progression, but acute myocardial injuries may also be related to ACE2 receptors in the heart.[86] ACE2 receptors are highly expressed in the heart and are involved in heart function.[86][89] A high incidence of thrombosis (31%) and venous thromboembolism (25%) have been found in ICU patients with COVID‑19 infections and may be related to poor prognosis.[90][91] Blood vessel dysfunction and clot formation (as suggested by high D-dimer levels) are thought to play a significant role in mortality, incidences of clots leading to pulmonary embolisms, and ischaemic events within the brain have been noted as complications leading to death in patients infected with SARS-CoV-2. Infection appears to set off a chain of vasoconstrictive responses within the body, constriction of blood vessels within the pulmonary circulation has also been posited as a mechanism in which oxygenation decreases alongside with the presentation of viral pneumonia.[92]

Another common cause of death is complications related to the kidneys[92]—SARS-CoV-2 directly infects kidney cells, as confirmed in post-mortem studies. Acute kidney injury is a common complication and cause of death; this is more significant in patients with already compromised kidney function, especially in people with pre-existing chronic conditions such as hypertension and diabetes which specifically cause nephropathy in the long run.[93]

Autopsies of people who died of COVID‑19 have found diffuse alveolar damage (DAD), and lymphocyte-containing inflammatory infiltrates within the lung.[94]

Immunopathology

Although SARS-COV-2 has a tropism for ACE2-expressing epithelial cells of the respiratory tract, patients with severe COVID‑19 have symptoms of systemic hyperinflammation. Clinical laboratory findings of elevated IL-2, IL-7, IL-6, granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), interferon-γ inducible protein 10 (IP-10), monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 (MCP-1), macrophage inflammatory protein 1-α (MIP-1α), and tumour necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) indicative of cytokine release syndrome (CRS) suggest an underlying immunopathology.[95]

Additionally, people with COVID‑19 and acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) have classical serum biomarkers of CRS, including elevated C-reactive protein (CRP), lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), D-dimer, and ferritin.[96]

Systemic inflammation results in vasodilation, allowing inflammatory lymphocytic and monocytic infiltration of the lung and the heart. In particular, pathogenic GM-CSF-secreting T-cells were shown to correlate with the recruitment of inflammatory IL-6-secreting monocytes and severe lung pathology in COVID‑19 patients.[97] Lymphocytic infiltrates have also been reported at autopsy.[94]

Diagnosis

.jpg)

The WHO has published several testing protocols for the disease.[99] The standard method of testing is real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (rRT-PCR).[100] The test is typically done on respiratory samples obtained by a nasopharyngeal swab; however, a nasal swab or sputum sample may also be used.[25][101] Results are generally available within a few hours to two days.[102][103] Blood tests can be used, but these require two blood samples taken two weeks apart, and the results have little immediate value.[104] Chinese scientists were able to isolate a strain of the coronavirus and publish the genetic sequence so laboratories across the world could independently develop polymerase chain reaction (PCR) tests to detect infection by the virus.[9][105][106] As of 4 April 2020, antibody tests (which may detect active infections and whether a person had been infected in the past) were in development, but not yet widely used.[107][108][109] The Chinese experience with testing has shown the accuracy is only 60 to 70%.[110] The FDA in the United States approved the first point-of-care test on 21 March 2020 for use at the end of that month.[111]

Diagnostic guidelines released by Zhongnan Hospital of Wuhan University suggested methods for detecting infections based upon clinical features and epidemiological risk. These involved identifying people who had at least two of the following symptoms in addition to a history of travel to Wuhan or contact with other infected people: fever, imaging features of pneumonia, normal or reduced white blood cell count, or reduced lymphocyte count.[112]

A study asked hospitalised COVID‑19 patients to cough into a sterile container, thus producing a saliva sample, and detected the virus in eleven of twelve patients using RT-PCR. This technique has the potential of being quicker than a swab and involving less risk to health care workers (collection at home or in the car).[62]

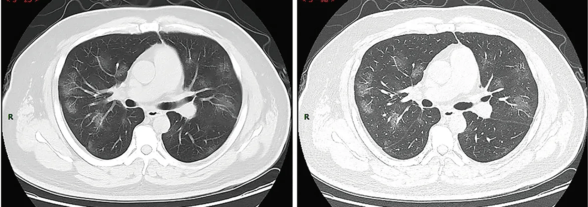

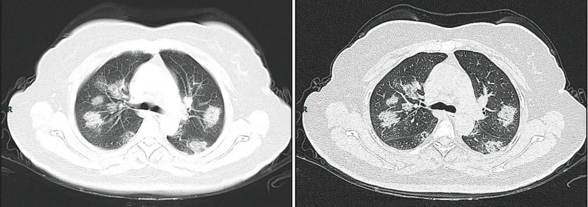

Along with laboratory testing, chest CT scans may be helpful to diagnose COVID-19 in individuals with a high clinical suspicion of infection but are not recommended for routine screening.[26][27] Bilateral multilobar ground-glass opacities with a peripheral, asymmetric, and posterior distribution are common in early infection.[26] Subpleural dominance, crazy paving (lobular septal thickening with variable alveolar filling), and consolidation may appear as the disease progresses.[26][113]

In late 2019, WHO assigned the emergency ICD-10 disease codes U07.1 for deaths from lab-confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection and U07.2 for deaths from clinically or epidemiologically diagnosed COVID‑19 without lab-confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection.[114]

Pathology

Few data are available about microscopic lesions and the pathophysiology of COVID‑19.[115][116] The main pathological findings at autopsy are:

- Macroscopy: pleurisy, pericarditis, lung consolidation and pulmonary oedema

- Four types of severity of viral pneumonia can be observed:

- minor pneumonia: minor serous exudation, minor fibrin exudation

- mild pneumonia: pulmonary oedema, pneumocyte hyperplasia, large atypical pneumocytes, interstitial inflammation with lymphocytic infiltration and multinucleated giant cell formation

- severe pneumonia: diffuse alveolar damage (DAD) with diffuse alveolar exudates. DAD is the cause of acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) and severe hypoxemia.

- healing pneumonia: organisation of exudates in alveolar cavities and pulmonary interstitial fibrosis

- plasmocytosis in BAL[117]

- Blood: disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC);[118] leukoerythroblastic reaction[119]

- Liver: microvesicular steatosis

Prevention

.gif)

Preventive measures to reduce the chances of infection include staying at home, avoiding crowded places, keeping distance from others, washing hands with soap and water often and for at least 20 seconds, practising good respiratory hygiene, and avoiding touching the eyes, nose, or mouth with unwashed hands.[125][126][127] The CDC recommends covering the mouth and nose with a tissue when coughing or sneezing and recommends using the inside of the elbow if no tissue is available.[125] Proper hand hygiene after any cough or sneeze is encouraged.[125] The CDC has recommended the use of cloth face coverings in public settings where other social distancing measures are difficult to maintain, in part to limit transmission by asymptomatic individuals.[128] The U.S. National Institutes of Health guidelines do not recommend any medication for prevention of COVID‑19, before or after exposure to the SARS-CoV-2 virus, outside of the setting of a clinical trial.[129]

Social distancing strategies aim to reduce contact of infected persons with large groups by closing schools and workplaces, restricting travel, and cancelling large public gatherings.[130] Distancing guidelines also include that people stay at least 6 feet (1.8 m) apart.[131] There is no medication known to be effective at preventing COVID‑19.[132] After the implementation of social distancing and stay-at-home orders, many regions have been able to sustain an effective transmission rate ("Rt") of less than one, meaning the disease is in remission in those areas.[133]

As a vaccine is not expected until 2021 at the earliest,[134] a key part of managing COVID‑19 is trying to decrease the epidemic peak, known as "flattening the curve".[121] This is done by slowing the infection rate to decrease the risk of health services being overwhelmed, allowing for better treatment of current cases, and delaying additional cases until effective treatments or a vaccine become available.[121][124]

According to the WHO, the use of masks is recommended only if a person is coughing or sneezing or when one is taking care of someone with a suspected infection.[135] For the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC) face masks "... could be considered especially when visiting busy closed spaces ..." but "... only as a complementary measure ..."[136] Several countries have recommended that healthy individuals wear face masks or cloth face coverings (like scarves or bandanas) at least in certain public settings, including China,[137] Hong Kong,[138] Spain,[139] Italy (Lombardy region),[140] and the United States.[128]

Those diagnosed with COVID‑19 or who believe they may be infected are advised by the CDC to stay home except to get medical care, call ahead before visiting a healthcare provider, wear a face mask before entering the healthcare provider's office and when in any room or vehicle with another person, cover coughs and sneezes with a tissue, regularly wash hands with soap and water and avoid sharing personal household items.[30][141] The CDC also recommends that individuals wash hands often with soap and water for at least 20 seconds, especially after going to the toilet or when hands are visibly dirty, before eating and after blowing one's nose, coughing or sneezing. It further recommends using an alcohol-based hand sanitiser with at least 60% alcohol, but only when soap and water are not readily available.[125]

For areas where commercial hand sanitisers are not readily available, the WHO provides two formulations for local production. In these formulations, the antimicrobial activity arises from ethanol or isopropanol. Hydrogen peroxide is used to help eliminate bacterial spores in the alcohol; it is "not an active substance for hand antisepsis". Glycerol is added as a humectant.[142]

Prevention efforts are multiplicative, with effects far beyond that of a single spread. Each avoided case leads to more avoided cases down the line, which in turn can stop the outbreak in its tracks.

Prevention efforts are multiplicative, with effects far beyond that of a single spread. Each avoided case leads to more avoided cases down the line, which in turn can stop the outbreak in its tracks.

Management

People are managed with supportive care, which may include fluid therapy, oxygen support, and supporting other affected vital organs.[143][144][145] The CDC recommends that those who suspect they carry the virus wear a simple face mask.[30] Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) has been used to address the issue of respiratory failure, but its benefits are still under consideration.[41][146] Personal hygiene and a healthy lifestyle and diet have been recommended to improve immunity.[147] Supportive treatments may be useful in those with mild symptoms at the early stage of infection.[148]

The WHO, the Chinese National Health Commission, and the United States' National Institutes of Health have published recommendations for taking care of people who are hospitalised with COVID‑19.[129][149][150] Intensivists and pulmonologists in the U.S. have compiled treatment recommendations from various agencies into a free resource, the IBCC.[151][152]

Medications

As of April 2020, there is no specific treatment for COVID‑19.[6][132] Research is, however, ongoing. For symptoms, some medical professionals recommend paracetamol (acetaminophen) over ibuprofen for first-line use.[153][154][155] The WHO and NIH do not oppose the use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) such as ibuprofen for symptoms,[129][156] and the FDA says currently there is no evidence that NSAIDs worsen COVID‑19 symptoms.[157]

While theoretical concerns have been raised about ACE inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers, as of 19 March 2020, these are not sufficient to justify stopping these medications.[129][158][159][160] Steroids, such as methylprednisolone, are not recommended unless the disease is complicated by acute respiratory distress syndrome.[161][162]

Medications to prevent blood clotting have been suggested for treatment,[90] and anticoagulant therapy with low molecular weight heparin appears to be associated with better outcomes in severe COVID‐19 showing signs of coagulopathy (elevated D-dimer).[163]

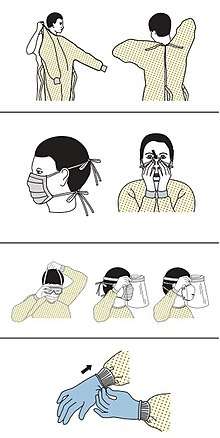

Protective equipment

Precautions must be taken to minimise the risk of virus transmission, especially in healthcare settings when performing procedures that can generate aerosols, such as intubation or hand ventilation.[165] For healthcare professionals caring for people with COVID‑19, the CDC recommends placing the person in an Airborne Infection Isolation Room (AIIR) in addition to using standard precautions, contact precautions, and airborne precautions.[166]

The CDC outlines the guidelines for the use of personal protective equipment (PPE) during the pandemic. The recommended gear is a PPE gown, respirator or facemask, eye protection, and medical gloves.[167][168]

When available, respirators (instead of facemasks) are preferred.[169] N95 respirators are approved for industrial settings but the FDA has authorised the masks for use under an Emergency Use Authorisation (EUA). They are designed to protect from airborne particles like dust but effectiveness against a specific biological agent is not guaranteed for off-label uses.[170] When masks are not available, the CDC recommends using face shields or, as a last resort, homemade masks.[171]

Mechanical ventilation

Most cases of COVID‑19 are not severe enough to require mechanical ventilation or alternatives, but a percentage of cases are.[172][173] The type of respiratory support for individuals with COVID‑19 related respiratory failure is being actively studied for people in the hospital, with some evidence that intubation can be avoided with a high flow nasal cannula or bi-level positive airway pressure.[174] Whether either of these two leads to the same benefit for people who are critically ill is not known.[175] Some doctors prefer staying with invasive mechanical ventilation when available because this technique limits the spread of aerosol particles compared to a high flow nasal cannula.[172]

Severe cases are most common in older adults (those older than 60 years,[172] and especially those older than 80 years).[176] Many developed countries do not have enough hospital beds per capita, which limits a health system's capacity to handle a sudden spike in the number of COVID‑19 cases severe enough to require hospitalisation.[177] This limited capacity is a significant driver behind calls to flatten the curve.[177] One study in China found 5% were admitted to intensive care units, 2.3% needed mechanical support of ventilation, and 1.4% died.[41] In China, approximately 30% of people in hospital with COVID‑19 are eventually admitted to ICU.[4]

Acute respiratory distress syndrome

Mechanical ventilation becomes more complex as acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) develops in COVID‑19 and oxygenation becomes increasingly difficult.[178] Ventilators capable of pressure control modes and high PEEP[179] are needed to maximise oxygen delivery while minimising the risk of ventilator-associated lung injury and pneumothorax.[180] High PEEP may not be available on older ventilators.

| Therapy | Recommendations |

|---|---|

| High-flow nasal oxygen | For SpO2 <93%. May prevent the need for intubation and ventilation |

| Tidal volume | 6mL per kg and can be reduced to 4mL/kg |

| Plateau airway pressure | Keep below 30 cmH2O if possible (high respiratory rate (35 per minute) may be required) |

| Positive end-expiratory pressure | Moderate to high levels |

| Prone positioning | For worsening oxygenation |

| Fluid management | Goal is a negative balance of 0.5–1.0L per day |

| Antibiotics | For secondary bacterial infections |

| Glucocorticoids | Not recommended |

Experimental treatment

Research into potential treatments started in January 2020,[181] and several antiviral drugs are in clinical trials.[182][183] Remdesivir appears to be the most promising.[132] Although new medications may take until 2021 to develop,[184] several of the medications being tested are already approved for other uses or are already in advanced testing.[185] Antiviral medication may be tried in people with severe disease.[143] The WHO recommended volunteers take part in trials of the effectiveness and safety of potential treatments.[186]

The FDA has granted temporary authorisation to convalescent plasma as an experimental treatment in cases where the person's life is seriously or immediately threatened. It has not undergone the clinical studies needed to show it is safe and effective for the disease.[187][188][189]

Information technology

In February 2020, China launched a mobile app to deal with the disease outbreak.[190] Users are asked to enter their name and ID number. The app can detect 'close contact' using surveillance data and therefore a potential risk of infection. Every user can also check the status of three other users. If a potential risk is detected, the app not only recommends self-quarantine, it also alerts local health officials.[191]

Big data analytics on cellphone data, facial recognition technology, mobile phone tracking, and artificial intelligence are used to track infected people and people whom they contacted in South Korea, Taiwan, and Singapore.[192][193] In March 2020, the Israeli government enabled security agencies to track mobile phone data of people supposed to have coronavirus. The measure was taken to enforce quarantine and protect those who may come into contact with infected citizens.[194] Also in March 2020, Deutsche Telekom shared aggregated phone location data with the German federal government agency, Robert Koch Institute, to research and prevent the spread of the virus.[195] Russia deployed facial recognition technology to detect quarantine breakers.[196] Italian regional health commissioner Giulio Gallera said he has been informed by mobile phone operators that "40% of people are continuing to move around anyway".[197] German government conducted a 48 hours weekend hackathon with more than 42.000 participants.[198][199] Two million people in the UK used an app developed in March 2020 by King's College London and Zoe to track people with COVID‑19 symptoms.[200] Also, the president of Estonia, Kersti Kaljulaid, made a global call for creative solutions against the spread of coronavirus.[201]

Psychological support

Individuals may experience distress from quarantine, travel restrictions, side effects of treatment, or fear of the infection itself. To address these concerns, the National Health Commission of China published a national guideline for psychological crisis intervention on 27 January 2020.[202][203]

The Lancet published a 14-page call for action focusing on the UK and stated conditions were such that a range of mental health issues was likely to become more common. BBC quoted Rory O'Connor in saying, "Increased social isolation, loneliness, health anxiety, stress and an economic downturn are a perfect storm to harm people's mental health and wellbeing."[204][205]

Prognosis

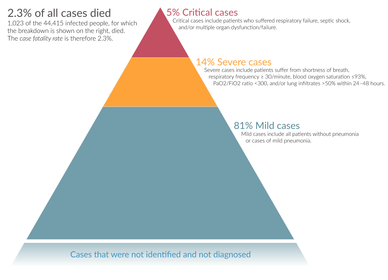

The severity of COVID‑19 varies. The disease may take a mild course with few or no symptoms, resembling other common upper respiratory diseases such as the common cold. Mild cases typically recover within two weeks, while those with severe or critical diseases may take three to six weeks to recover. Among those who have died, the time from symptom onset to death has ranged from two to eight weeks.[47]

Children make up a small proportion of reported cases, with about 1% of cases being under 10 years, and 4% aged 10-19 years.[22] They are likely to have milder symptoms and a lower chance of severe disease than adults; in those younger than 50 years, the risk of death is less than 0.5%, while in those older than 70 it is more than 8%.[212][213][214] Pregnant women may be at higher risk for severe infection with COVID-19 based on data from other similar viruses, like SARS and MERS, but data for COVID-19 is lacking.[215][216] In China, children acquired infections mainly through close contact with their parents or other family members who lived in Wuhan or had traveled there.[212]

In some people, COVID‑19 may affect the lungs causing pneumonia. In those most severely affected, COVID-19 may rapidly progress to acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) causing respiratory failure, septic shock, or multi-organ failure.[217][218] Complications associated with COVID‑19 include sepsis, abnormal clotting, and damage to the heart, kidneys, and liver. Clotting abnormalities, specifically an increase in prothrombin time, have been described in 6% of those admitted to hospital with COVID-19, while abnormal kidney function is seen in 4% of this group.[219] Approximately 20-30% of people who present with COVID‑19 demonstrate elevated liver enzymes (transaminases).[132] Liver injury as shown by blood markers of liver damage is frequently seen in severe cases.[220]

Some studies have found that the neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio (NLR) may be helpful in early screening for severe illness.[221]

Most of those who die of COVID‑19 have pre-existing (underlying) conditions, including hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and cardiovascular disease.[222] The Istituto Superiore di Sanità reported that out of 8.8% of deaths where medical charts were available for review, 97.2% of sampled patients had at least one comorbidity with the average patient having 2.7 diseases.[223] According to the same report, the median time between the onset of symptoms and death was ten days, with five being spent hospitalised. However, patients transferred to an ICU had a median time of seven days between hospitalisation and death.[223] In a study of early cases, the median time from exhibiting initial symptoms to death was 14 days, with a full range of six to 41 days.[224] In a study by the National Health Commission (NHC) of China, men had a death rate of 2.8% while women had a death rate of 1.7%.[225] Histopathological examinations of post-mortem lung samples show diffuse alveolar damage with cellular fibromyxoid exudates in both lungs. Viral cytopathic changes were observed in the pneumocytes. The lung picture resembled acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS).[47] In 11.8% of the deaths reported by the National Health Commission of China, heart damage was noted by elevated levels of troponin or cardiac arrest.[49] According to March data from the United States, 89% of those hospitalised had preexisting conditions.[226]

The availability of medical resources and the socioeconomics of a region may also affect mortality.[227] Estimates of the mortality from the condition vary because of those regional differences,[228] but also because of methodological difficulties. The under-counting of mild cases can cause the mortality rate to be overestimated.[229] However, the fact that deaths are the result of cases contracted in the past can mean the current mortality rate is underestimated.[230][231] Smokers were 1.4 times more likely to have severe symptoms of COVID‑19 and approximately 2.4 times more likely to require intensive care or die compared to non-smokers.[232]

Concerns have been raised about long-term sequelae of the disease. The Hong Kong Hospital Authority found a drop of 20% to 30% in lung capacity in some people who recovered from the disease, and lung scans suggested organ damage.[233] This may also lead to post-intensive care syndrome following recovery.[234]

| Age | 0–9 | 10–19 | 20–29 | 30–39 | 40–49 | 50–59 | 60–69 | 70–79 | 80-89 | 90+ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| China as of 11 February[207] | 0.0 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.4 | 1.3 | 3.6 | 8.0 | 14.8 | |

| Denmark as of 25 April[235] | 0.2 | 4.5 | 15.5 | 24.9 | 40.7 | |||||

| Italy as of 23 April[210] | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.4 | 0.9 | 2.6 | 10.0 | 24.9 | 30.8 | 26.1 |

| Netherlands as of 17 April[236] | 0.0 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.5 | 1.5 | 7.6 | 23.2 | 30.0 | 29.3 |

| Portugal as of 24 April[237] | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.3 | 0.6 | 2.8 | 8.5 | 16.5 | |

| S. Korea as of 15 April[208] | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.7 | 2.5 | 9.7 | 22.2 | |

| Spain as of 24 April[209] | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.6 | 1.3 | 4.4 | 13.2 | 20.3 | 20.1 |

| Switzerland as of 25 April[238] | 0.9 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.5 | 2.7 | 10.1 | 24.0 | |

| Age | 0–19 | 20–44 | 45–54 | 55–64 | 65–74 | 75–84 | 85+ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| United States as of 16 March[239] | 0.0 | 0.1–0.2 | 0.5–0.8 | 1.4–2.6 | 2.7–4.9 | 4.3–10.5 | 10.4–27.3 |

| Note: The lower bound includes all cases. The upper bound excludes cases that were missing data. | |||||||

| 0–9 | 10–19 | 20–29 | 30–39 | 40–49 | 50–59 | 60–69 | 70–79 | 80+ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Severe disease | 0.0 (0.0–0.0) |

0.04 (0.02–0.08) |

1.0 (0.62–2.1) |

3.4 (2.0–7.0) |

4.3 (2.5–8.7) |

8.2 (4.9–17) |

11 (7.0–24) |

17 (9.9–34) |

18 (11–38) |

| Death | 0.0016 (0.00016–0.025) |

0.0070 (0.0015–0.050) |

0.031 (0.014–0.092) |

0.084 (0.041–0.19) |

0.16 (0.076–0.32) |

0.60 (0.34–1.3) |

1.9 (1.1–3.9) |

4.3 (2.5–8.4) |

7.8 (3.8–13) |

| Total infection fatality rate is estimated to be 0.66% (0.39–1.3). Infection fatality rate is fatality per all infected individuals, regardless of whether they were diagnosed or had any symptoms. Numbers in parentheses are 95% credible intervals for the estimates. | |||||||||

Reinfection

As of March 2020, it was unknown if past infection provides effective and long-term immunity in people who recover from the disease.[241] Immunity is seen as likely, based on the behaviour of other coronaviruses,[242] but cases in which recovery from COVID‑19 have been followed by positive tests for coronavirus at a later date have been reported.[243][244][245][246] These cases are believed to be worsening of a lingering infection rather than re-infection.[246]

History

The virus is thought to be natural and has an animal origin,[76] through spillover infection.[247] The actual origin is unknown, but by December 2019 the spread of infection was almost entirely driven by human-to-human transmission.[207][248] A study of the first 41 cases of confirmed COVID‑19, published in January 2020 in The Lancet, revealed the earliest date of onset of symptoms as 1 December 2019.[249][250][251] Official publications from the WHO reported the earliest onset of symptoms as 8 December 2019.[252] Human-to-human transmission was confirmed by the WHO and Chinese authorities by 20 January 2020.[253][254]

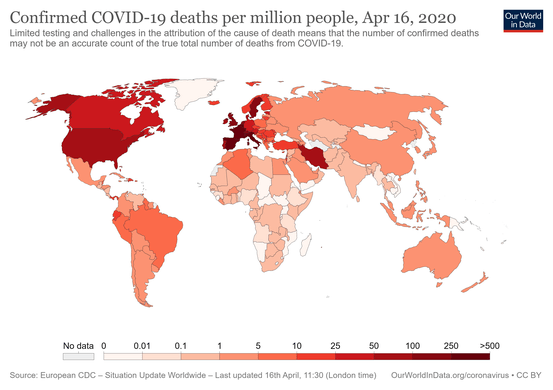

Epidemiology

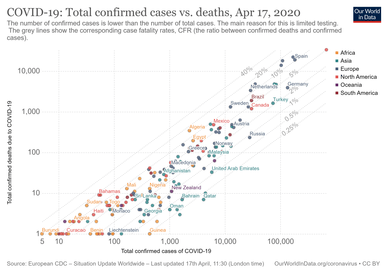

Several measures are commonly used to quantify mortality.[255] These numbers vary by region and over time and are influenced by the volume of testing, healthcare system quality, treatment options, time since the initial outbreak, and population characteristics such as age, sex, and overall health.[256]

The death-to-case ratio reflects the number of deaths divided by the number of diagnosed cases within a given time interval. Based on Johns Hopkins University statistics, the global death-to-case ratio is 7.0% (202,455/2,892,508) as of 25 April 2020.[7] The number varies by region.[257]

Other measures include the case fatality rate (CFR), which reflects the percent of diagnosed individuals who die from a disease, and the infection fatality rate (IFR), which reflects the percent of infected individuals (diagnosed and undiagnosed) who die from a disease. These statistics are not time-bound and follow a specific population from infection through case resolution. Many academics have attempted to calculate these numbers for specific populations.[258]

Infectious fatality rate

Our World in Data states that as of March 25, 2020, the infectious fatality rate (IFR) cannot be accurately calculated.[261] In February, the World Health Organization estimated the IFR at 0.94%, with a confidence interval between 0.37 percent to 2.9 percent.[262] The University of Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine (CEBM) estimated a global CFR of 0.72 percent and IFR of 0.1 percent to 0.36 percent.[263] According to CEBM, random antibody testing in Germany suggested an IFR of 0.37 percent there.[263] Firm lower limits to local infection fatality rates were established, such as in Bergamo province, where 0.57% of the population has died, leading to a minimum IFR of 0.57% in the province. This population fatality rate (PFR) minimum increases as more people get infected and run through their disease.[264][265] Similarly, as of April 22 in the New York City area, there were 15,411 deaths confirmed from COVID-19, and 19,200 excess deaths.[266]

Sex differences

The impact of the pandemic and its mortality rate are different for men and women.[267] Mortality is higher in men in studies conducted in China and Italy.[268][269][270] The highest risk for men is in their 50s, with the gap between men and women closing only at 90.[270] In China, the death rate was 2.8 percent for men and 1.7 percent for women.[270] The exact reasons for this sex-difference are not known, but genetic and behavioural factors could be a reason.[267] Sex-based immunological differences, a lower prevalence of smoking in women, and men developing co-morbid conditions such as hypertension at a younger age than women could have contributed to the higher mortality in men.[270] In Europe, of those infected with COVID‑19, 57% were men; of those infected with COVID‑19 who also died, 72% were men.[271] As of April 2020, the U.S. government is not tracking sex-related data of COVID‑19 infections.[272] Research has shown that viral illnesses like Ebola, HIV, influenza, and SARS affect men and women differently.[272] A higher percentage of health workers, particularly nurses, are women, and they have a higher chance of being exposed to the virus.[273] School closures, lockdowns, and reduced access to healthcare following the 2019–20 coronavirus pandemic may differentially affect the genders and possibly exaggerate existing gender disparity.[267][274]

Society and culture

Name

During the initial outbreak in Wuhan, China, the virus and disease were commonly referred to as "coronavirus" and "Wuhan coronavirus",[275][276][277] with the disease sometimes called "Wuhan pneumonia".[278][279] In the past, many diseases have been named after geographical locations, such as the Spanish flu,[280] Middle East Respiratory Syndrome, and Zika virus.[281]

In January 2020, the World Health Organisation recommended 2019-nCov[282] and 2019-nCoV acute respiratory disease[283] as interim names for the virus and disease per 2015 guidance and international guidelines against using geographical locations (e.g. Wuhan, China), animal species or groups of people in disease and virus names to prevent social stigma.[284][285][286]

The official names COVID‑19 and SARS-CoV-2 were issued by the WHO on 11 February 2020.[287] WHO chief Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus explained: CO for corona, VI for virus, D for disease and 19 for when the outbreak was first identified (31 December 2019).[288] The WHO additionally uses "the COVID‑19 virus" and "the virus responsible for COVID‑19" in public communications.[287] Both the disease and virus are commonly referred to as "coronavirus" in the media and public discourse.

Other animals

Humans appear to be capable of spreading the virus to some other animals. A domestic cat in Liège, Belgium, tested positive after it started showing symptoms (diarrhoea, vomiting, shortness of breath) a week later than its owner, who was also positive.[295] Tigers at the Bronx Zoo in New York, United States, tested positive for the virus and showed symptoms of COVID‑19, including a dry cough and loss of appetite.[296]

A study on domesticated animals inoculated with the virus found that cats and ferrets appear to be "highly susceptible" to the disease, while dogs appear to be less susceptible, with lower levels of viral replication. The study failed to find evidence of viral replication in pigs, ducks, and chickens.[297]

Research

No medication or vaccine is approved to treat the disease.[185] International research on vaccines and medicines in COVID‑19 is underway by government organisations, academic groups, and industry researchers.[298][299] In March, the World Health Organisation initiated the "SOLIDARITY Trial" to assess the treatment effects of four existing antiviral compounds with the most promise of efficacy.[300]

Vaccine

There is no available vaccine, but various agencies are actively developing vaccine candidates. Previous work on SARS-CoV is being used because both SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 use the ACE2 receptor to enter human cells.[301] Three vaccination strategies are being investigated. First, researchers aim to build a whole virus vaccine. The use of such a virus, be it inactive or dead, aims to elicit a prompt immune response of the human body to a new infection with COVID‑19. A second strategy, subunit vaccines, aims to create a vaccine that sensitises the immune system to certain subunits of the virus. In the case of SARS-CoV-2, such research focuses on the S-spike protein that helps the virus intrude the ACE2 enzyme receptor. A third strategy is that of the nucleic acid vaccines (DNA or RNA vaccines, a novel technique for creating a vaccination). Experimental vaccines from any of these strategies would have to be tested for safety and efficacy.[302]

On 16 March 2020, the first clinical trial of a vaccine started with four volunteers in Seattle, United States. The vaccine contains a harmless genetic code copied from the virus that causes the disease.[303]

Antibody-dependent enhancement has been suggested as a potential challenge for vaccine development for SARS-COV-2, but this is controversial.[304]

Medications

At least 29 phase II–IV efficacy trials in COVID‑19 were concluded in March 2020 or scheduled to provide results in April from hospitals in China.[305][306] There are more than 300 active clinical trials underway as of April 2020.[132] Seven trials were evaluating already approved treatments, including four studies on hydroxychloroquine or chloroquine.[306] Repurposed antiviral drugs make up most of the Chinese research, with nine phase III trials on remdesivir across several countries due to report by the end of April.[305][306] Other candidates in trials include vasodilators, corticosteroids, immune therapies, lipoic acid, bevacizumab, and recombinant angiotensin-converting enzyme 2.[306]

The COVID‑19 Clinical Research Coalition has goals to 1) facilitate rapid reviews of clinical trial proposals by ethics committees and national regulatory agencies, 2) fast-track approvals for the candidate therapeutic compounds, 3) ensure standardised and rapid analysis of emerging efficacy and safety data and 4) facilitate sharing of clinical trial outcomes before publication.[307][308]

Several existing medications are being evaluated for the treatment of COVID‑19,[185] including remdesivir, chloroquine, hydroxychloroquine, lopinavir/ritonavir, and lopinavir/ritonavir combined with interferon beta.[300][309] There is tentative evidence for efficacy by remdesivir, as of March 2020.[310][311] Clinical improvement was observed in patients treated with compassionate-use remdesivir.[312] Remdesivir inhibits SARS-CoV-2 in vitro.[313] Phase III clinical trials are underway in the U.S., China, and Italy.[185][305][314]

In 2020, a trial found that lopinavir/ritonavir was ineffective in the treatment of severe illness.[315] Nitazoxanide has been recommended for further in vivo study after demonstrating low concentration inhibition of SARS-CoV-2.[313]

There are mixed results as of 3 April 2020 as to the effectiveness of hydroxychloroquine as a treatment for COVID‑19, with some studies showing little or no improvement.[316][317] The studies of chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine with or without azithromycin have major limitations that have prevented the medical community from embracing these therapies without further study.[132]

Oseltamivir does not inhibit SARS-CoV-2 in vitro and has no known role in COVID‑19 treatment.[132]

Anti-cytokine storm

Cytokine release syndrome (CRS) can be a complication in the later stages of severe COVID‑19. There is preliminary evidence that hydroxychloroquine may have anti-cytokine storm properties.[318]

Tocilizumab has been included in treatment guidelines by China's National Health Commission after a small study was completed.[319][320] It is undergoing a phase 2 non-randomised trial at the national level in Italy after showing positive results in people with severe disease.[321][322] Combined with a serum ferritin blood test to identify cytokine storms, it is meant to counter such developments, which are thought to be the cause of death in some affected people.[323][324][325] The interleukin-6 receptor antagonist was approved by the FDA to undergo a phase III clinical trial assessing the medication's impact on COVID‑19 based on retrospective case studies for the treatment of steroid-refractory cytokine release syndrome induced by a different cause, CAR T cell therapy, in 2017.[326] To date, there is no randomised, controlled evidence that tocilizumab is an efficacious treatment for CRS. Prophylactic tocilizumab has been shown to increase serum IL-6 levels by saturating the IL-6R, driving IL-6 across the blood-brain barrier, and exacerbating neurotoxicity while having no impact on the incidence of CRS.[327]

Lenzilumab, an anti-GM-CSF monoclonal antibody, is protective in murine models for CAR T cell-induced CRS and neurotoxicity and is a viable therapeutic option due to the observed increase of pathogenic GM-CSF secreting T-cells in hospitalised patients with COVID‑19.[328]

The Feinstein Institute of Northwell Health announced in March a study on "a human antibody that may prevent the activity" of IL-6.[329]

Passive antibodies

Transferring purified and concentrated antibodies produced by the immune systems of those who have recovered from COVID‑19 to people who need them is being investigated as a non-vaccine method of passive immunisation.[330] This strategy was tried for SARS with inconclusive results.[330] Viral neutralisation is the anticipated mechanism of action by which passive antibody therapy can mediate defence against SARS-CoV-2. Other mechanisms, however, such as antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity and/or phagocytosis, may be possible.[330] Other forms of passive antibody therapy, for example, using manufactured monoclonal antibodies, are in development.[330] Production of convalescent serum, which consists of the liquid portion of the blood from recovered patients and contains antibodies specific to this virus, could be increased for quicker deployment.[331]

See also

- Coronavirus diseases, a group of closely related syndromes

- Coronavirus recession

- Disease X, a WHO term

- Li Wenliang, a doctor at Central Hospital of Wuhan who died of COVID-19 after raising awareness of its spread

- List of unproven methods against COVID-19

Notes

References

- Chen N, Zhou M, Dong X, Qu J, Gong F, Han Y, et al. (February 2020). "Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study". Lancet. 395 (10223): 507–513. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30211-7. PMC 7135076. PMID 32007143.

- Han X, Cao Y, Jiang N, Chen Y, Alwalid O, Zhang X, et al. (March 2020). "Novel Coronavirus Pneumonia (COVID-19) Progression Course in 17 Discharged Patients: Comparison of Clinical and Thin-Section CT Features During Recovery". Clinical Infectious Diseases. doi:10.1093/cid/ciaa271. PMID 32227091.

- "Covid-19, n." Oxford English Dictionary. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- "Interim Clinical Guidance for Management of Patients with Confirmed Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19)". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 6 April 2020. Archived from the original on 2 March 2020. Retrieved 19 April 2020.

- "Symptoms of Coronavirus". U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 20 March 2020. Archived from the original on 30 January 2020.

- "Q&A on coronaviruses". World Health Organization. 8 April 2020. Archived from the original on 20 January 2020. Retrieved 12 April 2020.

- "COVID-19 Dashboard by the Center for Systems Science and Engineering (CSSE) at Johns Hopkins University (JHU)". ArcGIS. Johns Hopkins University. Retrieved 25 April 2020.

- "Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19)—Symptoms and causes". Mayo Clinic. Retrieved 14 April 2020.

- Hui DS, I Azhar E, Madani TA, Ntoumi F, Kock R, Dar O, et al. (February 2020). "The continuing 2019-nCoV epidemic threat of novel coronaviruses to global health—The latest 2019 novel coronavirus outbreak in Wuhan, China". Int J Infect Dis. 91: 264–66. doi:10.1016/j.ijid.2020.01.009. PMID 31953166.

- "WHO Director-General's opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID-19". World Health Organization (WHO) (Press release). 11 March 2020. Archived from the original on 11 March 2020. Retrieved 12 March 2020.

- "Q&A on coronaviruses (COVID-19)". World Health Organization (WHO). Archived from the original on 20 January 2020. Retrieved 11 March 2020.

- Hopkins, Claire. "Loss of sense of smell as marker of COVID-19 infection". Ear, Nose and Throat surgery body of United Kingdom. Retrieved 28 March 2020.

- Mehta, Puja; McAuley, Daniel F.; Brown, Michael; Sanchez, Emilie; Tattersall, Rachel S.; Manson, Jessica J. (28 March 2020). "COVID-19: consider cytokine storm syndromes and immunosuppression". The Lancet. 395 (10229): 1033–1034. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30628-0. ISSN 0140-6736. PMID 32192578.

- "Q&A on coronaviruses". World Health Organization (WHO). Archived from the original on 20 January 2020. Retrieved 27 January 2020.

- Velavan, T. P.; Meyer, C. G. (March 2020). "The COVID-19 epidemic". Tropical Medicine & International Health. n/a (n/a): 278–80. doi:10.1111/tmi.13383. PMID 32052514.

- "How COVID-19 Spreads". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 2 April 2020. Archived from the original on 3 April 2020. Retrieved 3 April 2020.

- Bourouiba L (March 2020). "Turbulent Gas Clouds and Respiratory Pathogen Emissions: Potential Implications for Reducing Transmission of COVID-19". JAMA. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.4756. PMID 32215590.

- "Q & A on COVID-19". European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Archived from the original on 5 February 2020. Retrieved 23 March 2020.

- "Modes of transmission of virus causing COVID-19: implications for IPC precaution recommendations". World Health Organization. 29 March 2020. Retrieved 3 April 2020.

According to current evidence, COVID-19 virus is primarily transmitted between people through respiratory droplets and contact routes.

- Organization (WHO), World Health (28 March 2020). "FACT: #COVID19 is NOT airborne". @WHO. Retrieved 3 April 2020.

These droplets are too heavy to hang in the air. They quickly fall on floors or surfaces.

- "New coronavirus stable for hours on surfaces". National Institutes of Health. 17 March 2020. Archived from the original on 23 March 2020. Retrieved 23 March 2020.

- "Q & A on COVID-19". European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control.

- van Doremalen N, Bushmaker T, Morris DH, Holbrook MG, Gamble A, Williamson BN, et al. (March 2020). "Aerosol and Surface Stability of SARS-CoV-2 as Compared with SARS-CoV-1". New England Journal of Medicine: NEJMc2004973. doi:10.1056/NEJMc2004973. ISSN 0028-4793. PMC 7121658. PMID 32182409.

- "Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) Situation Report—73" (PDF). World Health Organization. 2 April 2020. Retrieved 3 April 2020.

- "Interim Guidelines for Collecting, Handling, and Testing Clinical Specimens from Persons for Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19)". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 11 February 2020. Archived from the original on 4 March 2020. Retrieved 26 March 2020.

- Salehi, Sana; Abedi, Aidin; Balakrishnan, Sudheer; Gholamrezanezhad, Ali (14 March 2020). "Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19): A Systematic Review of Imaging Findings in 919 Patients". American Journal of Roentgenology: 1–7. doi:10.2214/AJR.20.23034. ISSN 0361-803X. PMID 32174129.

- "ACR Recommendations for the use of Chest Radiography and Computed Tomography (CT) for Suspected COVID-19 Infection". American College of Radiology. 22 March 2020. Archived from the original on 28 March 2020.

- "Advice for public". World Health Organization (WHO). Archived from the original on 26 January 2020. Retrieved 25 February 2020.

- "Guidance on social distancing for everyone in the UK". GOV.UK. Archived from the original on 24 March 2020. Retrieved 25 March 2020.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (5 April 2020). "What to Do if You Are Sick". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Archived from the original on 14 February 2020. Retrieved 24 April 2020.

- "When and how to use masks". www.who.int. Archived from the original on 7 March 2020. Retrieved 24 April 2020.

- Feng, Shuo; Shen, Chen; Xia, Nan; Song, Wei; Fan, Mengzhen; Cowling, Benjamin J. (20 March 2020). "Rational use of face masks in the COVID-19 pandemic". The Lancet Respiratory Medicine. 0. doi:10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30134-X. ISSN 2213-2600. PMC 7118603. PMID 32203710.

- Tait, Robert (30 March 2020). "Czechs get to work making masks after government decree". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 30 March 2020. Retrieved 31 March 2020.

- "How to Protect Yourself & Others". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 8 April 2020. Archived from the original on 26 February 2020. Retrieved 9 April 2020.

- "Statement on the second meeting of the International Health Regulations (2005) Emergency Committee regarding the outbreak of novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV)". World Health Organization (WHO). Archived from the original on 31 January 2020. Retrieved 11 February 2020.

- Mahtani, S.; Berger, M.; O'Grady, S.; Iati, M. (6 February 2020). "Hundreds of evacuees to be held on bases in California; Hong Kong and Taiwan restrict travel from mainland China". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 7 February 2020. Retrieved 11 February 2020.

- "WHO Situation Report #87" (PDF). WHO. 16 April 2020.

- Palus, Shannon (27 March 2020). "The Key Stat in the NYTimes' Piece About Losing Your Sense of Smell Was Wrong". Slate Magazine. Archived from the original on 28 March 2020. Retrieved 28 March 2020.

- Iacobucci, Gareth (2020). "Sixty seconds on ... anosmia". BMJ. 368: m1202. doi:10.1136/bmj.m1202. ISSN 1756-1833. PMID 32209546.

- Yang, Xiaobo; Yu, Yuan; Xu, Jiqian; et al. (24 February 2020). "Clinical course and outcomes of critically ill patients with SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a single-centered, retrospective, observational study". Lancet. doi:10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30079-5. PMC 7102538.

... 52 critically ill adult patients ... fever (98%) ... [of which] fever was not detected at the onset of illness in six (11·5%) ...

- Guan WJ, Ni ZY, Hu Y, Liang WH, Ou CQ, He JX, et al. (February 2020). "Clinical Characteristics of Coronavirus Disease 2019 in China". The New England Journal of Medicine. Massachusetts Medical Society. doi:10.1056/nejmoa2002032. PMC 7092819. PMID 32109013.

- Chen N, Zhou M, Dong X, Qu J, Gong F, Han Y, et al. (February 2020). "Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study". Lancet. 395 (10223): 507–513. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30211-7. PMID 32007143.

- Hessen MT (27 January 2020). "Novel Coronavirus Information Center: Expert guidance and commentary". Elsevier Connect. Archived from the original on 30 January 2020. Retrieved 31 January 2020.

- Wei, Xiao-Shan; Wang, Xuan; Niu, Yi-Ran; Ye, Lin-Lin; Peng, Wen-Bei; Wang, Zi-Hao; Yang, Wei-Bing; Yang, Bo-Han; Zhang, Jian-Chu; Ma, Wan-Li; Wang, Xiao-Rong; Zhou, Qiong (26 February 2020). "Clinical Characteristics of SARS-CoV-2 Infected Pneumonia with Diarrhea". doi:10.2139/ssrn.3546120.

- Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, Ren L, Zhao J, Hu Y, et al. (February 2020). "Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China". Lancet. 395 (10223): 497–506. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. PMID 31986264.

- Lai, Chih-Cheng; Shih, Tzu-Ping; Ko, Wen-Chien; Tang, Hung-Jen; Hsueh, Po-Ren (1 March 2020). "Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) and coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19): The epidemic and the challenges". International Journal of Antimicrobial Agents. 55 (3): 105924. doi:10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2020.105924. ISSN 0924-8579. PMC 7127800. PMID 32081636.

- Report of the WHO-China Joint Mission on Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) (PDF) (Report). World Health Organization (WHO). 16–24 February 2020. Archived (PDF) from the original on 29 February 2020. Retrieved 21 March 2020.

- Australia, Healthdirect (18 March 2020). "healthdirect Symptom Checker". www.healthdirect.gov.au. Retrieved 19 April 2020.

- Zheng YY, Ma YT, Zhang JY, Xie X (March 2020). "COVID-19 and the cardiovascular system". Nature Reviews. Cardiology. doi:10.1038/s41569-020-0360-5. PMID 32139904.

- Xydakis MS, Dehgani-Mobaraki P, Holbrook EH, Geisthoff UW, Bauer C, Hautefort C, et al. (15 April 2020). "Smell and taste dysfunction in patients with COVID-19". Lancet Infectious Diseases. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30293-0. PMC 7159875. Retrieved 21 April 2020.

- World Health Organization (19 February 2020). "Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): situation report, 29". World Health Organization (WHO). hdl:10665/331118.

- "Q&A on coronaviruses (COVID-19): How long is the incubation period for COVID-19?". World Health Organization (WHO). Archived from the original on 20 January 2020. Retrieved 26 February 2020.

- Lauer, Stephen A.; Grantz, Kyra H.; Bi, Qifang; Jones, Forrest K.; Zheng, Qulu; Meredith, Hannah R.; Azman, Andrew S.; Reich, Nicholas G.; Lessler, Justin (10 March 2020). "The Incubation Period of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) From Publicly Reported Confirmed Cases: Estimation and Application". Annals of Internal Medicine. doi:10.7326/M20-0504. ISSN 0003-4819. PMC 7081172. PMID 32150748. Archived from the original on 24 March 2020. Retrieved 24 March 2020.

- "Report 9: Impact of non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPIs) to reduce COVID-19 mortality and healthcare demand" (PDF). Imperial College COVID-19 Response Team. 16 March 2020. Retrieved 21 April 2020. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Mizumoto, Kenji; Kagaya, Katsushi; Zarebski, Alexander; Chowell, Gerardo (2020). "Estimating the asymptomatic proportion of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) cases on board the Diamond Princess cruise ship, Yokohama, Japan, 2020" (PDF). Euro Surveillance. doi:10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2020.25.10.2000180. Retrieved 21 April 2020.

- "Clinical Questions about COVID-19: Questions and Answers". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 11 February 2020. Archived from the original on 14 February 2020. Retrieved 31 March 2020.

- Lai, Chich-Cheng; Liu, Yen Hung; Wang, Cheng-Yi; Wang, Ya-Hui; Hsueh, Shun-Chung; Yen, Muh-Yen; Ko, Wen-Chien; Hsueh, Po-Ren (4 March 2020). "Asymptomatic carrier state, acute respiratory disease, and pneumonia due to severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2): Facts and myths". Journal of Microbiology, Immunology, and Infection. doi:10.1016/j.jmii.2020.02.012. PMC 7128959. PMID 32173241.

- Bai, Yan; Yao, Lingsheng; Wei, Tao; Tian, Fei; Jin, Dong-Yan; Chen, Lijuan; Wang, Meiyun (21 February 2020). "Presumed Asymptomatic Carrier Transmission of COVID-19". JAMA. 323 (14): 1406. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.2565. ISSN 0098-7484. PMC 7042844. PMID 32083643.

- "China Reveals 1,541 Symptom-Free Virus Cases Under Pressure". www.bloomberg.com. 31 March 2020. Retrieved 31 March 2020.

- "코로나19 국내 발생현황 브리핑 (20. 03. 16. 14시)". ktv.go.kr (in Korean). Retrieved 31 March 2020.

- "Staying at home and away from other people (social distancing)—Coronavirus (COVID-19)—NHS". NHS.uk. Retrieved 24 April 2020.

- To, Kelvin Kai-Wang; Tsang, Owen Tak-Yin; Yip, Cyril Chik-Yan; Chan, Kwok-Hung; et al. (12 February 2020). "Consistent Detection of 2019 Novel Coronavirus in Saliva". Clinical Infectious Diseases. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/cid/ciaa149. PMC 7108139. PMID 32047895.

- Asadi, Sima; Wexler, Anthony; Cappa, Christopher; et al. (20 February 2019). "Aerosol emission and superemission during human speech increase with voice loudness" (PDF). Nature. 9. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-38808-z. PMID 30787335.

... simply talking in a loud voice would increase the rate at which an infected individual releases pathogen-laden particles into the air ... For example, an airborne infectious disease might spread more efficiently in a school cafeteria than a library, or in a noisy hospital waiting room than a quiet ward.

- Loh NW, Tan Y, Taculod J, Gorospe B, Teope AS, Somani J, et al. (March 2020). "The impact of high-flow nasal cannula (HFNC) on coughing distance: implications on its use during the novel coronavirus disease outbreak". Canadian Journal of Anesthesia. doi:10.1007/s12630-020-01634-3. PMC 7090637. PMID 32189218.

- "Modes of transmission of virus causing COVID-19: implications for IPC precaution recommendations". www.who.int. Retrieved 29 March 2020.

- "Rapid Expert Consultation on the Possibility of Bioaerosol Spread of SARS-CoV-2 for the COVID-19 Pandemic". The National Academies Press. 1 April 2020. Retrieved 24 April 2020.

- Sanche, Steven; Lin, Yen Ting; Xu, Chonggang; Romero-Severson, Ethan; Hengartner, Nick; Ke, Ruian (July 2020). "Early Release—High Contagiousness and Rapid Spread of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2—Volume 26, Number 7". Emerging Infectious Diseases journal. doi:10.3201/eid2607.200282.

- CDC (11 February 2020). "Recommendation Regarding the Use of Cloth Face Coverings, Especially in Areas of Significant Community-Based Transmission". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved 25 April 2020.

- CDC (13 April 2020). "Transmission". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved 25 April 2020.

- "Q&A on coronaviruses (COVID-19)". WHO. 3 March 2020. Retrieved 25 April 2020.

- Moriyama M, Hugentobler WJ, Iwasaki A (20 March 2020). "Seasonality of Respiratory Viral Infections". Annual Review of Virology. 7. doi:10.1146/annurev-virology-012420-022445. PMID 32196426.

- Holden, Emily, Do you need to wash your groceries? And other advice for shopping safely, The Guardian, Thursday, April 2, 2020

- "COVID-19 prevention: Why soap, sanitizer and warm water work against coronavirus—CNN". Edition.cnn.com. 24 March 2020. Retrieved 7 April 2020.

- Kampf, G.; Todt, D.; Pfaender, S.; Steinmann, E. (March 2020). "Persistence of coronaviruses on inanimate surfaces and their inactivation with biocidal agents". The Journal of Hospital Infection. 104 (3): 246–251. doi:10.1016/j.jhin.2020.01.022. PMC 7132493. PMID 32035997.

- "Outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2): increased transmission beyond China—fourth update" (PDF). European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. 14 February 2020. Retrieved 8 March 2020.

- Andersen KG, Rambaut A, Lipkin WI, Holmes EC, Garry RF (17 March 2020). "The proximal origin of SARS-CoV-2". Nature Medicine. 26 (4): 450–452. doi:10.1038/s41591-020-0820-9. ISSN 1546-170X. PMC 7095063. PMID 32284615.

- Zhu N, Zhang D, Wang W, Li X, Yang B, Song J, et al. (February 2020). "A Novel Coronavirus from Patients with Pneumonia in China, 2019". The New England Journal of Medicine. 382 (8): 727–733. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2001017. PMC 7092803. PMID 31978945.

- Cyranoski D (26 February 2020). "Mystery deepens over animal source of coronavirus". Nature. 579 (7797): 18–19. Bibcode:2020Natur.579...18C. doi:10.1038/d41586-020-00548-w. PMID 32127703.

- Letko M, Marzi A, Munster V (2020). "Functional assessment of cell entry and receptor usage for SARS-CoV-2 and other lineage B betacoronaviruses". Nature Microbiology. 5 (4): 562–569. doi:10.1038/s41564-020-0688-y. PMID 32094589.

- Zhang H, Penninger JM, Li Y, Zhong N, Slutsky AS (March 2020). "Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) as a SARS-CoV-2 receptor: molecular mechanisms and potential therapeutic target". Intensive Care Medicine. 46 (4): 586–590. doi:10.1007/s00134-020-05985-9. PMC 7079879. PMID 32125455.

- Xu H, Zhong L, Deng J, Peng J, Dan H, Zeng X, et al. (February 2020). "High expression of ACE2 receptor of 2019-nCoV on the epithelial cells of oral mucosa". International Journal of Oral Science. 12 (1): 8. doi:10.1038/s41368-020-0074-x. PMC 7039956. PMID 32094336.

- Gurwitz D (March 2020). "Angiotensin receptor blockers as tentative SARS‐CoV‐2 therapeutics". Drug Development Research. doi:10.1002/ddr.21656. PMID 32129518.

- Gu, Jinyang; Han, Bing; Wang, Jian (27 February 2020). "COVID-19: Gastrointestinal manifestations and potential fecal-oral transmission". Gastroenterology. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2020.02.054. ISSN 0016-5085. PMC 7130192. PMID 32142785.

- Hamming, I.; Timens, W.; Bulthuis, M. L. C.; Lely, A. T.; Navis, G. J.; Goor, H. van (2004). "Tissue distribution of ACE2 protein, the functional receptor for SARS coronavirus. A first step in understanding SARS pathogenesis". The Journal of Pathology. 203 (2): 631–637. doi:10.1002/path.1570. ISSN 1096-9896. PMC 7167720. PMID 15141377.

- Li, Yan-Chao; Bai, Wan-Zhu; Hashikawa, Tsutomu (21 April 2020). "The neuroinvasive potential of SARS-CoV2 may play a role in the respiratory failure of COVID-19 patients". Journal of Medical Virology. 92 (6): 552–555. doi:10.1002/jmv.25728 – via Wiley Online Library.

- Zheng, Ying-Ying; Ma, Yi-Tong; Zhang, Jin-Ying; Xie, Xiang (5 March 2020). "COVID-19 and the cardiovascular system". Nature Reviews Cardiology: 1–2. doi:10.1038/s41569-020-0360-5. ISSN 1759-5010. PMC 7095524.

- Huang, Chaolin; Wang, Yeming; Li, Xingwang; Ren, Lili; Zhao, Jianping; Hu, Yi; Zhang, Li; Fan, Guohui; Xu, Jiuyang; Gu, Xiaoying; Cheng, Zhenshun (February 2020). "Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China". The Lancet. 395 (10223): 497–506. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(20)30183-5. ISSN 0140-6736. PMC 7159299.

- Wang, Dawei; Hu, Bo; Hu, Chang; Zhu, Fangfang; Liu, Xing; Zhang, Jing; Wang, Binbin; Xiang, Hui; Cheng, Zhenshun; Xiong, Yong; Zhao, Yan (17 March 2020). "Clinical Characteristics of 138 Hospitalized Patients With 2019 Novel Coronavirus-Infected Pneumonia in Wuhan, China". JAMA. 323 (11): 1061–1069. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.1585. ISSN 0098-7484. PMC 7042881. PMID 32031570.

- Turner, Anthony J.; Hiscox, Julian A.; Hooper, Nigel M. (1 June 2004). "ACE2: from vasopeptidase to SARS virus receptor". Trends in Pharmacological Sciences. 25 (6): 291–294. doi:10.1016/j.tips.2004.04.001. ISSN 0165-6147. PMC 7119032. PMID 15165741.

- Klok, F.A.; Kruip, M.J.H.A.; van der Meer, N.J.M.; Arbous, M.S.; Gommers, D.A.M.P.J.; Kant, K.M.; Kaptein, F.H.J.; van Paassen, J.; Stals, M.A.M.; Huisman, M.V.; Endeman, H. (April 2020). "Incidence of thrombotic complications in critically ill ICU patients with COVID-19". Thrombosis Research. doi:10.1016/j.thromres.2020.04.013. ISSN 0049-3848. PMC 7146714.

- Cui, Songping; Chen, Shuo; Li, Xiunan; Liu, Shi; Wang, Feng (9 April 2020). "Prevalence of venous thromboembolism in patients with severe novel coronavirus pneumonia". Journal of Thrombosis and Haemostasis. doi:10.1111/jth.14830.

- Science, Magazine (18 March 2020). "How does coronavirus kill? Clinicians trace a ferocious rampage through the body, from brain to toes". www.science mag.com. Retrieved 17 April 2020.

- Diao, Bo; Wang, Chenhui; Wang, Rongshuai; Feng, Zeqing; Tan, Yingjun; Wang, Huiming; Wang, Changsong; Liu, Liang; Liu, Ying; Liu, Yueping; Wang, Gang; Yuan, Zilin; Ren, Liang; Wu, Yuzhang; Chen, Yongwen (10 April 2020). "Human Kidney is a Target for Novel Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) Infection". medRxiv: 2020.03.04.20031120. doi:10.1101/2020.03.04.20031120 – via www.medrxiv.org.

- Barton L, Duval E, Stroberg E, Ghosh S, Mukhopadhyay S (April 2020). "COVID-19 autopsies, Oklahoma, USA". American Journal of Clinical Pathology. doi:10.1093/ajcp/aqaa062. PMID 32275742.

- Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, Ren L, Zhao J, Hu Y, et al. (February 2020). "Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China". Lancet. 395 (10223): 497–506. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. PMC 7159299. PMID 31986264.

- Zhang C, Wu Z, Li JW, Zhao H, Wang GQ (March 2020). "The cytokine release syndrome (CRS) of severe COVID-19 and Interleukin-6 receptor (IL-6R) antagonist Tocilizumab may be the key to reduce the mortality". International Journal of Antimicrobial Agents: 105954. doi:10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2020.105954. PMC 7118634. PMID 32234467.

- Zhou Y, Fu B, Zheng X, Wang D, Zhao C, Qi Y, et al. (2020). "Aberrant pathogenic GM-CSF+ T cells and inflammatory CD14+CD16+ monocytes in severe pulmonary syndrome patients of a new coronavirus". bioRxiv Pre-print. doi:10.1101/2020.02.12.945576.

- "CDC Tests for 2019-nCoV". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 5 February 2020. Archived from the original on 14 February 2020. Retrieved 12 February 2020.

- "Laboratory testing for 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) in suspected human cases". World Health Organization (WHO). Archived from the original on 17 March 2020. Retrieved 13 March 2020.

- "2019 Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV) Situation Summary". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 30 January 2020. Archived from the original on 26 January 2020. Retrieved 30 January 2020.

- "Real-Time RT-PCR Panel for Detection 2019-nCoV". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 29 January 2020. Archived from the original on 30 January 2020. Retrieved 1 February 2020.

- "Curetis Group Company Ares Genetics and BGI Group Collaborate to Offer Next-Generation Sequencing and PCR-based Coronavirus (2019-nCoV) Testing in Europe". GlobeNewswire News Room. 30 January 2020. Archived from the original on 31 January 2020. Retrieved 1 February 2020.

- Brueck H (30 January 2020). "There's only one way to know if you have the coronavirus, and it involves machines full of spit and mucus". Business Insider. Archived from the original on 1 February 2020. Retrieved 1 February 2020.

- "Laboratory testing for 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) in suspected human cases". Archived from the original on 21 February 2020. Retrieved 26 February 2020.

- Cohen J, Normile D (January 2020). "New SARS-like virus in China triggers alarm" (PDF). Science. 367 (6475): 234–35. Bibcode:2020Sci...367..234C. doi:10.1126/science.367.6475.234. PMID 31949058. Archived (PDF) from the original on 11 February 2020. Retrieved 11 February 2020.

- "Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 data hub". NCBI. Archived from the original on 21 March 2020. Retrieved 4 March 2020.

- Petherick, Anna (4 April 2020). "Developing antibody tests for SARS-CoV-2". The Lancet. 395 (10230): 1101–1102. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(20)30788-1. ISSN 0140-6736. PMID 32247384.

- Vogel, Gretchen (19 March 2020). "New blood tests for antibodies could show true scale of coronavirus pandemic". Science. doi:10.1126/science.abb8028. ISSN 0036-8075.

- Pang J, Wang MX, Ang IY, Tan SH, Lewis RF, Chen JI, et al. (February 2020). "Potential Rapid Diagnostics, Vaccine and Therapeutics for 2019 Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV): A Systematic Review". Journal of Clinical Medicine. 9 (3): 623. doi:10.3390/jcm9030623. PMC 7141113. PMID 32110875.

- AFP News Agency (11 April 2020). "How false negatives are complicating COVID-19 testing". Al Jazeera website Retrieved 12 April 2020.