Coronation of Elizabeth II

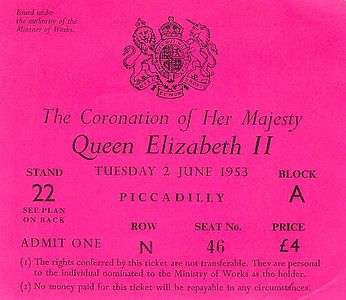

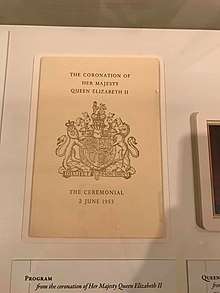

The coronation of Elizabeth II took place on 2 June 1953 at Westminster Abbey, London.[1] She acceded to the throne at the age of 25 upon the death of her father, George VI, on 6 February 1952, being proclaimed queen by her privy and executive councils shortly afterwards. The coronation was held more than one year later because of the tradition of allowing an appropriate length of time to pass after a monarch dies before holding such festivals. It also gave the planning committees adequate time to make preparations for the ceremony. During the service, Elizabeth took an oath, was anointed with holy oil, invested with robes and regalia, and crowned Queen of the United Kingdom, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, Pakistan, and Ceylon (now Sri Lanka).[2]

Coronation portrait of Elizabeth with her husband, Philip | |

| Date | 2 June 1953 |

|---|---|

| Location | London, United Kingdom |

| Participants |

|

Celebrations took place across the Commonwealth realms and a commemorative medal was issued. It was the first British coronation to be fully televised; television cameras had not been allowed inside the abbey during her father's coronation in 1937. Elizabeth's was the fourth and last British coronation of the 20th century. It was estimated to have cost £1.57 million (c. £43,427,400 in 2019).

Preparations

The one-day ceremony took 14 months of preparation: the first meeting of the Coronation Commission was in April 1952,[3] under the chairmanship of the Queen's husband, Philip, Duke of Edinburgh.[4][5] Other committees were also formed, such as the Coronation Joint Committee and the Coronation Executive Committee,[6] both chaired by the Duke of Norfolk who,[7] by convention as Earl Marshal, had overall responsibility for the event. Many physical preparations and decorations along the route were the responsibility of David Eccles, Minister of Works. Eccles described his role and that of the Earl Marshal: "The Earl Marshal is the producer – I am the stage manager..."[8]

The committees involved high commissioners from other Commonwealth realms, reflecting the international nature of the coronation; however, officials from other Commonwealth realms declined invitations to participate in the event because the governments of those countries considered the ceremony to be a religious rite unique to Britain. As Canadian Prime Minister Louis St. Laurent said at the time: "In my view the Coronation is the official enthronement of the Sovereign as Sovereign of the UK. We are happy to attend and witness the Coronation of the Sovereign of the UK but we are not direct participants in that function."[9] The Coronation Commission announced in June 1952 that the coronation would take place on 2 June 1953.[10]

Norman Hartnell was commissioned by the Queen to design the outfits for all members of the royal family, including Elizabeth's coronation gown. His design for the gown evolved through nine proposals, and the final version resulted from his own research and numerous meetings with the Queen: a white silk dress embroidered with floral emblems of the countries of the Commonwealth at the time: the Tudor rose of England, Scottish thistle, Welsh leek, shamrock for Northern Ireland, wattle of Australia, maple leaf of Canada, the New Zealand silver fern, South Africa's protea, two lotus flowers for India and Ceylon, and Pakistan's wheat, cotton and jute.[11][12]

Elizabeth rehearsed for the occasion with her maids of honour. A sheet was used in place of the velvet train, and a formation of chairs stood in for the carriage. She also wore the Imperial State Crown while going about her daily business – at her desk, during tea, and while reading a newspaper – so that she could become accustomed to its feel and weight.[11] Elizabeth took part in two full rehearsals at Westminster Abbey, on 22 and 29 May,[13] though some sources claim that she attended one or "several" rehearsals.[14][15] The Duchess of Norfolk usually stood in for the Queen at rehearsals.

Elizabeth's grandmother Queen Mary had died on 24 March 1953, having stated in her will that her death should not affect the planning of the coronation, and the event went ahead as scheduled.[10] It was estimated to cost £1.57 million (c. £38,680,000 in 2016[16]), which included stands along the procession route to accommodate 96,000 people, lavatories, street decorations, outfits, car hire, repairs to the state coach, and alterations to the Queen's regalia.[17]

Event

The Coronation ceremony of Elizabeth II followed a similar pattern to the coronations of the kings and queens before her, being held in Westminster Abbey, and involving the peerage and clergy. However, for the new Queen, several parts of the ceremony were markedly different.

Television

Millions across Britain watched the coronation live on the BBC Television Service, and many purchased or rented television sets for the event. The coronation of the Queen was the first to be televised in full; the BBC's cameras had not been allowed inside Westminster Abbey for her father's coronation in 1937, and had covered only the procession outside.[18] There had been considerable debate within the British Cabinet on the subject, with Prime Minister Winston Churchill against the idea; but, Elizabeth refused his advice on this matter and insisted the event take place before television cameras,[19] as well as those filming with experimental 3D technology.[n 1][20] The event was also filmed in colour, separately from the BBC's black and white television broadcast.[21]

Elizabeth's coronation was also the first major world event to be broadcast internationally on television. To make sure Canadians could see it on the same day, RAF Canberras flew BBC film recordings of the ceremony across the Atlantic Ocean to be broadcast by the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation,[22] the first non-stop flights between the United Kingdom and the Canadian mainland. At Goose Bay, Labrador, the first batch of film was transferred to a Royal Canadian Air Force CF-100 jet fighter for the further trip to Montreal. In all, three such flights were made as the coronation proceeded, with the first and second Canberras taking the second and third batches of film, respectively, to Montreal.[23] The following day, a film was flown west to Vancouver, whose CBC Television affiliate had yet to sign on. The film was escorted by the RCMP to the Peace Arch Border Crossing, where it was then escorted by the Washington State Patrol to Bellingham, where it was shown as the inaugural broadcast of KVOS-TV, a new station whose signal reached into the Lower Mainland of British Columbia, allowing viewers there to see the coronation as well, though on a one-day delay.

US networks NBC and CBS made similar arrangements to have films flown in relays back to the United States for same-day broadcast, but used slower propeller-driven aircraft. The struggling ABC network arranged to re-transmit the CBC broadcast, taking the on-the-air signal from the CBC's Toronto station and feeding the network from ABC's affiliate in Buffalo, New York and, as a result, beat the other two networks to air by more than 90 minutes — and at considerably lower cost.

Although it did not as yet have full-time television service, film was also dispatched to Australia aboard a Qantas airliner, which arrived in Sydney in a record time of 53 hours 28 minutes.[24] The worldwide television audience for the coronation was estimated to be 277 million.[25]

Procession

Along a route lined with sailors, soldiers, and airmen and women from across the British Empire and Commonwealth,[n 2][26] guests and officials passed in a procession before about three million spectators gathered in the streets of London, some having camped overnight in their spot to ensure a view of the monarch, and others having access to specially built stands and scaffolding along the route.[27] For those not present to witness the event, more than 200 microphones were stationed along the path and in Westminster Abbey, with 750 commentators broadcasting descriptions in 39 languages;[23] more than twenty million viewers around the world watched the coverage.[27]

The procession included foreign royalty and heads of state riding to Westminster Abbey in various carriages, so many that volunteers ranging from wealthy businessmen to rural landowners were required to supplement the insufficient ranks of regular footmen.[27] The first royal coach left Buckingham Palace and moved down the Mall, which was filled with flag-waving and cheering crowds. It was followed by the Irish State Coach carrying Queen Elizabeth the Queen Mother, who wore the circlet of her crown bearing the Koh-i-Noor diamond. Queen Elizabeth II proceeded through London from Buckingham Palace, through Trafalgar Square, and towards the abbey in the Gold State Coach. Attached to the shoulders of her dress, the Queen wore the Robe of State, a 6-yard (5.5 metre) long, hand woven silk velvet cloak lined with Canadian ermine that required the assistance of the Queen's maids of honour—Lady Jane Vane-Tempest-Stewart, Lady Anne Coke, Lady Moyra Hamilton, Lady Mary Baillie-Hamilton, Lady Jane Heathcote-Drummond-Willoughby, Lady Rosemary Spencer-Churchill and the Duchess of Devonshire[28][29]—to carry.[11][30]

The return procession followed a route that was 5 miles (8 kilometres) in length, passing through Whitehall, Trafalgar Square, Pall Mall, Hyde Park Corner, Marble Arch, Oxford Circus, and finally down the Mall to Buckingham Palace. 29,000 service personnel from Britain and across the Commonwealth marched in a procession that was two miles (3.2 kilometres) long and took 45 minutes to pass any given point. A further 15,800 lined the route.[31] The parade was led by Colonel Burrows of the War Office staff and four regimental bands. Then came the colonial contingents, then troops from the Commonwealth realms, followed by the Royal Air Force, the British Army, the Royal Navy, and finally the Household Brigade.[32] Behind the marching troops was a carriage procession led by the rulers of the British protectorates, including the Queen of Tonga, the Commonwealth prime ministers, the princes and princesses of the blood royal, and the Queen Mother. Preceded by the heads of the British Armed Forces on horseback, the Gold State Coach was escorted by the Yeomen of the Guard and the Household Cavalry and was followed by the Queen's aides-de-camp.[33]

Guests

After being closed since the Queen's accession for coronation preparations, Westminster Abbey was opened at 6 am on Coronation Day to the approximately 8,000 guests invited from across the Commonwealth of Nations;[n 3][27][36] more prominent individuals, such as members of the Queen's family and foreign royalty, the peers of the United Kingdom, heads of state, Members of Parliament from the Queen's various legislatures,[37] and the like, arrived after 8:30 a.m. Tonga's Queen Sālote was a guest, and was noted for her cheery demeanour while riding in an open carriage through London in the rain.[38] General George Marshall, the United States Secretary of State who implemented the Marshall Plan, was appointed chairman of the US delegation to the coronation and attended the ceremony along with his wife, Katherine.[39]

Guests seated on stools were able to purchase their stools following the ceremony, with the profits going towards the cost of the Coronation.[40]

Ceremony

Preceding the Queen into Westminster Abbey was St Edward's Crown, carried into the abbey by the Lord High Steward of England, then the Viscount Cunningham of Hyndhope, who was flanked by two other peers, while the Archbishops and Bishops Assistant (Durham and Bath and Wells) of the Church of England, in their copes and mitres, waited outside the Great West Door for the arrival of the Queen. When the Queen arrived at about 11:00 am,[11][19] she found that the friction between her robes and the carpet caused her difficulty moving forward, and she said to the Archbishop of Canterbury, Geoffrey Fisher, "Get me started!"[19] Once going, the procession, which included the various High Commissioners of the Commonwealth carrying banners bearing the shields of the coats of arms of their respective nations,[41] moved inside the abbey, up the central aisle and through the choir to the stage, as the choirs sang "I was glad", an imperial setting of Psalm 122, vv. 1–3, 6, and 7 by Sir Hubert Parry.[42] As Elizabeth prayed at and then seated herself on the Chair of Estate to the south of the altar, the Bishops carried in the religious paraphernalia—the bible, paten and chalice—and the peers holding the coronation regalia handed them over to the Archbishop of Canterbury, who, in turn, passed them to the Dean of Westminster, Alan Campbell Don, to be placed on the altar.[43]

After the Queen moved to stand before King Edward's Chair (Coronation Chair), she turned, following as Fisher, along with the Lord High Chancellor of Great Britain (the Viscount Simonds), Lord Great Chamberlain of England (the Marquess of Cholmondeley), Lord High Constable of England (the Viscount Alanbrooke) and Earl Marshal of the United Kingdom (the Duke of Norfolk), all led by the Garter Principal King of Arms (George Bellew), asked the audience in each direction of the compass separately: "Sirs, I here present unto you Queen Elizabeth, your undoubted Queen: wherefore all you who are come this day to do your homage and service, are you willing to do the same?" The crowd would reply "God save Queen Elizabeth" every time,[44] to each of which the Queen would curtsey in return.[41]

Seated again on the Chair of Estate, Elizabeth then took the Coronation Oath as administered by the Archbishop of Canterbury. In the lengthy oath, the Queen swore to govern each of her countries according to their respective laws and customs, to mete out law and justice with mercy, to uphold Protestantism in the United Kingdom and protect the Church of England and preserve its bishops and clergy. She proceeded to the altar where she stated, "The things which I have here promised, I will perform, and keep. So help me God", before kissing the Bible and putting the royal sign-manual to the oath as the Bible was returned to the Dean of Westminster.[45] From him the Moderator of the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland, James Pitt-Watson, took the Bible and presented it to the Queen again, saying,

Our gracious Queen: to keep your Majesty ever mindful of the law and the Gospel of God as the Rule for the whole life and government of Christian Princes, we present you with this Book, the most valuable thing that this world affords. Here is Wisdom; This is the royal Law; These are the lively Oracles of God.

Elizabeth returned the book to Pitt-Watson, who placed it back with the Dean of Westminster.[46]

The communion service was then conducted, involving prayers by both the clergy and Elizabeth, Fisher asking, "O God... Grant unto this thy servant Elizabeth, our Queen, the spirit of wisdom and government, that being devoted unto thee with her whole heart, she may so wisely govern, that in her time thy Church may be in safety, and Christian devotion may continue in peace", before reading various excerpts from the First Epistle of Peter, Psalms, and the Gospel of Matthew.[47] Elizabeth was then anointed as the choir sang "Zadok the Priest"; the Queen's jewellery and crimson cape were removed by the Earl of Ancaster and the Mistress of the Robes,[11] the Duchess of Devonshire and, wearing only a simple, white linen dress also designed by Hartnell to completely cover the coronation gown, she moved to be seated in the Coronation Chair. There, Fisher, assisted by the Dean of Westminster, made a cross on the Queen's forehead with holy oil made from the same base as had been used in the coronation of her father.[19] At the Queen's request, the actual anointing ceremony was not televised.[48]

From the altar, the Dean passed to the Lord Great Chamberlain the spurs, which were presented to the Queen and then placed back on the altar. The Sword of State was then handed to Elizabeth, who, after a prayer was uttered by Fisher, placed it herself on the altar, and the peer who had been previously holding it took it back again after paying a sum of 100 shillings.[49] The Queen was then invested with the Armills (bracelets), Stole Royal, Robe Royal and the Sovereign's Orb, followed by the Queen's Ring, the Sovereign's Sceptre with Cross and the Sovereign's Sceptre with Dove. With the first two items on and in her right hand and the latter in her left, Queen Elizabeth was crowned by the Archbishop of Canterbury, with the crowd chanting "God save the queen!" three times at the exact moment St Edward's Crown touched the monarch's head. The princes and peers gathered then put on their coronets and a 21-gun salute was fired from the Tower of London.[50]

With the benediction read, Elizabeth moved to the throne and the Archbishop of Canterbury and all the Bishops offered to her their fealty, after which, while the choir sang, the peers of the United Kingdom—led by the royal peers: the Queen's husband; Prince Henry, Duke of Gloucester; and Prince Edward, Duke of Kent—each proceeded, in order of precedence, to pay their personal homage and allegiance to Elizabeth.

When the last baron had completed this task, the assembly shouted "God save Queen Elizabeth. Long live Queen Elizabeth. May the Queen live for ever!"[51] Having removed all her royal regalia, Elizabeth knelt and took the communion, including a general confession and absolution, and, along with the congregation, recited the Lord's Prayer.[52]

Now wearing the Imperial State Crown and holding the Sceptre with the Cross and the Orb, and as the gathered guests sang "God Save the Queen", Elizabeth left Westminster Abbey through the nave and apse, out the Great West Door.

Music

.jpg)

Although many had assumed that the Master of the Queen's Musick, Arnold Bax, would be the director of music for the coronation, it was decided instead to appoint the organist and master of the choristers at the abbey, William McKie, who had been in charge of music at the royal wedding in 1947. McKie convened an advisory committee with Arnold Bax and Sir Ernest Bullock, who had directed the music for the previous coronation.[53]

When it came to choosing the music, tradition required that Handel's "Zadok the Priest" and Parry's "I was glad" were included amongst the anthems. Other choral works included were the 16th century "Rejoice in the Lord alway" and Samuel Sebastian Wesley's "Thou wilt keep him in perfect peace". Another tradition was that new work be commissioned from the leading composers of the day: Ralph Vaughan Williams composed a new motet "O Taste and See", William Walton composed a setting for the "Te Deum", and the Canadian composer Healey Willan wrote an anthem "O Lord our Governor".[26][54] Four new orchestral pieces were planned; Arthur Bliss composed "Processional"; William Walton, "Orb and Sceptre"; and Arnold Bax, "Coronation March". Benjamin Britten had agreed to compose a piece, but he caught influenza and then had to deal with flooding at Aldeburgh, so nothing was forthcoming. Edward Elgar's "Pomp and Circumstance March No. 1 in D" was played immediately before Bax's march at the end of the ceremony.[55] An innovation, at the suggestion of Vaughan Williams, was the inclusion of a hymn in which the congregation could participate. This proved controversial and was not included in the programme until the Queen had been consulted and found to be in favour; Vaughan Williams wrote an elaborate arrangement of the traditional Scottish metrical psalm, "Old 100th", which included military trumpet fanfares[56] and was sung before the communion.[42] Gordon Jacob wrote a choral arrangement of God Save the Queen, also with trumpet fanfares.[57]

The choir for the coronation was a combination of the choirs of Westminster Abbey, St Paul's Cathedral, the Chapel Royal, and Saint George's Chapel, Windsor. In addition to those established choirs, the Royal School of Church Music conducted auditions to find twenty boy trebles from parish church choirs representing the various regions of the United Kingdom. Along with twelve trebles chosen from various British cathedral choirs, the selected boys spent the month beforehand training at Addington Palace.[58] The final complement of choristers comprised 182 boy trebles, 37 male altos, 62 tenors and 67 basses. Together with a full orchestra, conducted by Sir Adrian Boult, the total number of musicians was 480.[55]

Celebrations, monuments and media

All across the Queen's realms, the rest of the Commonwealth, and in other parts of the world, coronation celebrations were held. The Queen Elizabeth II Coronation Medal was also presented to thousands of recipients throughout the Queen's realms and in Canada, New Zealand, South Africa and the UK, commemorative coins were issued.[59] Three million bronze coronation medallions were ordered by the Canadian government, struck by the Royal Canadian Mint and distributed to schoolchildren across the country; the obverse showed Elizabeth's effigy and the reverse the royal cypher above the word CANADA, all circumscribed by ELIZABETH II REGINA CORONATA MCMLIII.[60]

As at the coronation of George VI, acorns shed from oaks in Windsor Great Park, near Windsor Castle, were shipped around the Commonwealth and planted in parks, school grounds, cemeteries and private gardens to grow into what are known as Royal Oaks or Coronation Oaks.[61]

In London, the Queen hosted a coronation luncheon, for which the recipe coronation chicken was devised,[62] and a fireworks show was mounted on Victoria Embankment.[27] Further, street parties were mounted around the United Kingdom. The Coronation Cup football tournament was held at Hampden Park, Glasgow in May, and[19] two weeks before the coronation, the children's literary magazine Collins Magazine rebranded itself as The Young Elizabethan.[63] News that Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay had reached the summit of Mount Everest arrived in Britain on Elizabeth's coronation day; the New Zealand, American, and British media dubbed it "a coronation gift for the new Queen".[64]

Military tattoos, horse races, parades, and fireworks displays were mounted in Canada. The country's governor general, Vincent Massey, proclaimed the day a national holiday and presided over celebrations on Parliament Hill in Ottawa, where the Queen's coronation speech was broadcast and her personal royal standard flown from the Peace Tower.[65][66] Later, a public concert was held on Parliament Hill and the Governor General hosted a ball at Rideau Hall.[65] In Newfoundland, 90,000 boxes of sweets were given to children, some having theirs delivered by Royal Canadian Air Force drops, and in Quebec, 400,000 people turned out in Montreal, some 100,000 at Jeanne-Mance Park alone. A multicultural show was put on at Exhibition Place in Toronto, square dances and exhibitions took place in the Prairie provinces and in Vancouver the Chinese community performed a public lion dance.[67] On the Korean Peninsula, Canadian soldiers serving in the Korean War acknowledged the day by firing red, white, and blue coloured smoke shells at the enemy and drank rum rations.

Coronation review of the fleet

On 15 June 1953, the Queen attended a fleet review at Spithead, off the coast at Portsmouth. There were more Commonwealth naval ships present than at the 1937 coronation review, though a third of them were frigates or smaller vessels. Major Royal Navy units included Britain's last battleship, HMS Vanguard, and four fleet and three light aircraft carriers. The Royal Australian Navy and the Royal Canadian Navy also each included a light carrier in their contingents (HMAS Sydney (R17) and HMCS Magnificent (CVL 21)).[68] Using the frigate HMS Surprise as a royal yacht, the Queen and royal family started to review the lines of anchored ships at 3:30 p.m., finally anchoring at 5:10 p.m. This was followed by a fly-past of some 300 naval aircraft. After the Queen transferred to Vanguard for dinner, the day concluded with the Illumination of the fleet and a fireworks display.[69]

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Coronation of Elizabeth II. |

- List of participants in the coronation procession of Elizabeth II

- 1953 Coronation Honours

- The Queen's Beasts, heraldic statues placed outside Westminster Abbey representing Elizabeth's genealogy

- Canadian Coronation Contingent

Notes

- This footage was in 2010 used in the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation's first 3D television broadcast, the first time the images had been shown on television.[20]

- Including 856 representing the Canadian Army, Royal Canadian Navy, and Royal Canadian Air Force.[26]

- From Canada came the Prime Minister, Louis St. Laurent, and five other members of the federal Cabinet, the Chief Justice, the Speakers of the House of Commons and Senate, the Leaders of Her Majesty's Loyal Opposition in the same two houses, and the Leader of the Government in the Senate,[34] Lieutenant Governor of Ontario Louis Breithaupt and his premier, Leslie Frost, as well as Premier of Saskatchewan Tommy Douglas, Quebec Cabinet ministers Onésime Gagnon and John Samuel Bourque,[35] Mayor of Toronto Allan A. Lamport, and Chief of the Squamish Nation Joe Mathias.[23][22]

References

- "1953: Queen Elizabeth takes coronation oath". BBC. Retrieved 29 May 2018.

- Museum of New Zealand. "The coronation and visit of Queen Elizabeth II". New Zealand Government. Retrieved 18 January 2018.

- Bousfield, Arthur; Toffoli, Gary (2002). Fifty Years the Queen. Toronto: Dundurn Press. p. 74. ISBN 978-1-55002-360-2.

- Bousfield 2002, p. 100

- "Coronation June 2 Next Year". The Glasgow Herald. 29 April 1952. Retrieved 19 March 2016.

- "Family's Ancient Right to Prepare for Coronation". The Age. 2 June 1953. Retrieved 21 March 2016.

- "Staging Coronation Complex Problem". Ottawa Citizen. 1 June 1953. Retrieved 19 March 2016.

- Herbert, A. P. (27 April 1953). "Here Comes the Queen". Life. p. 98. Retrieved 19 March 2016.

- Trepanier, Peter (2006), "A Not Unwilling Subject: Canada and Her Queen", in Coates, Colin M. (ed.), Majesty in Canada, Hamilton: Dundurn Press, pp. 144–145, ISBN 9781550025866, retrieved 16 October 2012

- Bousfield 2002, p. 77

- Thomas, Pauline Weston. "Coronation Gown of Queen Elizabeth II: The Queen's Robes, Part 2". Fashion-Era. Retrieved 18 December 2009.

- Cotton, Belinda; Ramsey, Ron. "By Appointment: Norman Hartnell's sample for the Coronation dress of Queen Elizabeth II". National Gallery of Australia. Archived from the original on 30 May 2012. Retrieved 12 February 2010.

- McDowell, Colin (1985). A Hundred Years of Royal Style. London: Muller, Blond & White. p. 70. ISBN 978-0-584-11071-5.

- Bradford, Sarah (1 May 1997). Elizabeth: A Biography of Britain's Queen. London: Riverhead Trade. p. 186. ISBN 978-1-57322-600-4.

- Brooke-Little, John (1980). Royal Ceremonies of State. London: Littlehampton Book Services Ltd. p. 52. ISBN 978-0-600-37628-6.

- United Kingdom Gross Domestic Product deflator figures follow the Measuring Worth "consistent series" supplied in Thomas, Ryland; Williamson, Samuel H. (2018). "What Was the U.K. GDP Then?". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved 2 February 2020.

- Morris, Bob (2018). Inaugurating a New Reign: Planning for Accession and Coronation. University College London. pp. 23–24. ISBN 978-1-903903-82-7.

- BBC Handbook 1938. London: British Broadcasting Corporation. 1938. pp. 38–39.

- "The Coronation of Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II". Historic UK. Retrieved 20 December 2009.

- Szklarski, Cassandra (10 June 2010). "Put on those specs, couch potatoes – 3D poised to reinvent TV: tech guru". News1130. Archived from the original on 17 July 2011. Retrieved 11 August 2010.

- "Early Color Television: British Experimental Field Sequential Color System". Early Television Museum. Retrieved 23 June 2012.

- Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. "Society > The Monarchy > Canada's New Queen > Coronation of Queen Elizabeth > The Story". CBC. Retrieved 17 December 2009.

- Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. "Society > The Monarchy > Canada's New Queen > Coronation of Queen Elizabeth > Did You Know?". CBC. Retrieved 17 December 2009.

- "Fifty Years Ago - 1953". airwaysmuseum.com. The Civil Aviation Historical Society & Airways Museum. 2003. Retrieved 12 August 2018.

- Davison, Janet (2 June 2013). "Queen's coronation made history for Canada – and for television". www.cbc.ca. CBC News. Retrieved 12 August 2018.

- McCreery, Christopher (2012). Commemorative Medals of The Queen's Reign in Canada, 1952–2012. Toronto: Dundurn Press. p. 49. ISBN 9781459707580.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "On This Day > 2nd June > 1953: Queen Elizabeth takes coronation oath". British Broadcasting Corporation. 2 June 1953. Retrieved 19 December 2009.

- Demoskoff, Yvonne. "Yvonne's Royalty Home Page > Queen Elizabeth II's ladies-in-waiting at her coronation, 1953". Yvonne Demoskoff. Archived from the original on 4 June 2011. Retrieved 16 December 2009.

- Sampson, Annabel (15 October 2019). "Lady Anne Glenconner's memoir reveals her as the ultimate in royal companions". Tatler. Archived from the original on 8 November 2019.

- Lady Anne Glenconner (2019). "4". Lady in waiting : my extraordinary life in the shadow of the crown. ISBN 9781529359084.

- Arlott, John and others (1953) Elizabeth Crowned Queen, Odhams Press Limited (pp. 15–25)

- "The Ceremonial of the Coronation of Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II" (PDF). Supplement to the London Gazette. pp. 6253–6263. 17 November 1952. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 December 2013. Retrieved 24 November 2013.CS1 maint: location (link)

- London Gazette pp. 6264–6270

- McCreery 2012, p. 48

- "Society > The Monarchy > Coronation of Queen Elizabeth". CBC. Archived from the original on 27 December 2010. Retrieved 4 July 2009.

- Brooke-Little 1980, p. 55

- Royal Household. "Her Majesty The Queen > Accession and Coronation". Queen's Printer. Retrieved 18 December 2009.

- "Our Constitution > Timeline > Post 1875 > 1953: Queen Salote attends Queen Elizabeth II coronation". Director and Secretariat to the Constitutional and Electoral Commission. Retrieved 20 December 2009.

- Thompson, Rachel Yarnell (2014). Marshall: A Statesman Shaped in the Crucible of War. Leesburg, Virginia: George C. Marshall International Center. ISBN 9780615929033.

- Government of Nova Scotia. "The Diamond Jubilee of Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II > Diamond Jubilee Photos". Queen's Printer for Nova Scotia. Retrieved 29 February 2012.

- Bousfield 2002, p. 78

- "The Form and Order of Service that is to be performed and the Ceremonies that are to be observed in the Coronation of Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II in the Abbey Church of St. Peter, Westminster, on Tuesday, the second day of June, 1953". An Anglican Liturgical Library. Retrieved 15 December 2009.

- An Anglican Liturgical Library, II

- An Anglican Liturgical Library, III

- An Anglican Liturgical Library, IV

- An Anglican Liturgical Library, V

- An Anglican Liturgical Library, VI

- https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-22764987

- An Anglican Liturgical Library, VIII

- An Anglican Liturgical Library, IX–XI

- An Anglican Liturgical Library, XII–XIV

- An Anglican Liturgical Library, XV

- Wilkinson, James (2011). The Queen's Coronation: The Inside Story. Scala Publishers Ltd. p. 24. ISBN 978-1-85759-735-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wilkinson 2011, p. 27

- Wilkinson 2011, p. 28

- Wilkinson 2011, p. 25

- Range, Matthias (2012). Music and Ceremonial at British Coronations: From James I to Elizabeth II. Cambridge University Press. pp. 256–257. ISBN 978-1-107-02344-4.

- "RSCM choristers at the Queen's Coronation in 1953". The Royal School of Church Music. Archived from the original on 10 January 2014. Retrieved 10 January 2014.

- "The Coronation Crown Collection". Coincraft. Archived from the original on 8 July 2011. Retrieved 14 January 2010.

- McCreery 2012, p. 51

- Whiting, Marguerite (2008). "Royal Acorns" (PDF). Trillium. Parkhill: Ontario Horticultural Association. Spring 2008: 13. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 November 2008. Retrieved 3 July 2009.

- "Coronation Chicken recipe". British Broadcasting Corporation. 2 June 2003. Retrieved 19 December 2009.

- Melman, Billie (2006). The Culture of History: English Uses of the Past 1800–1953. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 284. ISBN 978-0-19-929688-0.

- Reuters (2 June 1953), "2 of British Team Conquer Everest", The New York Times, p. 1, retrieved 18 December 2009

- McCreery 2012, p. 50

- Government of Nova Scotia. "The Diamond Jubilee of Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II > The Queen's Personal Canadian Flag". Queen's Printer for Nova Scotia. Retrieved 29 February 2012.

- Bousfield 2002, pp. 83–85

- Willmott, H P (2010). The Last Century of Sea Power: From Washington to Tokyo, 1922–1945. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. p. 25. ISBN 978-0-253-35214-9. Retrieved 29 July 2014.

- Day, A. (22 May 1953). "Coronation Review of the Fleet" (PDF). Cloud Observers Association. Retrieved 3 May 2015.

Further reading

- Clancy, Laura. "'Queen's Day – TV's Day': the British monarchy and the media industries", Contemporary British History, vol. 33, no. 3 (2019), pp. 427–450.

- Feingold, Ruth P. "Every little girl can grow up to be queen: the coronation and The Virgin in the Garden." Literature & History 22.2 (2013): 73–90.

- Örnebring, Henrik. "Revisiting the Coronation: a Critical Perspective on the Coronation of Queen Elizabeth II in 1953." Nordicom Review 25, no. 1-2 online(2004)

- Shils, Edward, and Michael Young. "The meaning of the coronation." The Sociological Review 1.2 (1953): 63–81.

- Weight, Richard. Patriots: National Identity in Britain 1940–2000 (Pan Macmillan, 2013) pp 211–56.