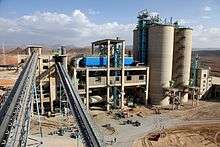

Construction

Construction is the process of constructing a building or infrastructure.[1] Construction differs from manufacturing in that manufacturing typically involves mass production of similar items without a designated purchaser, while construction typically takes place on location for a known client.[2] Construction as an industry comprises six to nine percent of the gross domestic product of developed countries.[3] Construction starts with planning, design, and financing; it continues until the project is built and ready for use.

.jpg)

Large-scale construction requires collaboration across multiple disciplines. A project manager normally manages the budget on the job, and a construction manager, design engineer, construction engineer or architect supervises it. Those involved with the design and execution must consider zoning requirements, environmental impact of the job, scheduling, budgeting, construction-site safety, availability and transportation of building materials, logistics, inconvenience to the public caused by construction delays and bidding. Large construction projects are sometimes referred to as megaprojects.

Etymology

Construction is a general term meaning the art and science to form objects, systems, or organizations,[4] and comes from Latin constructio (from com- "together" and struere "to pile up") and Old French construction.[5] To construct is the verb: the act of building, and the noun construction: how a building was built, the nature of its structure.

Types

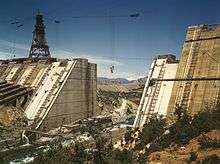

In general, there are three sectors of construction: buildings, infrastructure and industrial.[6] Building construction is usually further divided into residential and non-residential (commercial/institutional). Infrastructure is often called heavy civil or heavy engineering that includes large public works, dams, bridges, highways, railways, water or wastewater and utility distribution. Industrial construction includes refineries, process chemical, power generation, mills and manufacturing plants. There are also other ways to break the industry into sectors or markets.[7]

Industry sectors

_3_Det._4%2C_place_trimming_on_birthing_spaces_being_built_for_Afg.jpg)

Engineering News-Record (ENR), a trade magazine for the construction industry, each year compiles and reports data about the size of design and construction companies. In 2014, ENR compiled the data in nine market segments divided as transportation, petroleum, buildings, power, industrial, water, manufacturing, sewer/waste, telecom, hazardous waste and a tenth category for other projects.[8] In their reporting, they used data on transportation, sewer, hazardous waste and water to rank firms as heavy contractors.[9]

The Standard Industrial Classification and the newer North American Industry Classification System have a classification system for companies that perform or engage in construction. To recognize the differences of companies in this sector, it is divided into three subsectors: building construction, heavy and civil engineering construction, and specialty trade contractors. There are also categories for construction service firms (e.g., engineering, architecture) and construction managers (firms engaged in managing construction projects without assuming direct financial responsibility for completion of the construction project).[10][11]

Building construction

Building construction is the process of adding structure to real property or construction of buildings. The majority of building construction jobs are small renovations, such as addition of a room, or renovation of a bathroom. Often, the owner of the property acts as laborer, paymaster, and design team for the entire project.[12] Although building construction projects consist of common elements such as design, financial, estimating and legal considerations, projects of varying sizes may reach undesirable end results, such as structural collapse, cost overruns, and/or litigation. For this reason, those with experience in the field make detailed plans and maintain careful oversight during the project to ensure a positive outcome.

Commercial building construction is procured privately or publicly utilizing various delivery methodologies, including cost estimating, hard bid, negotiated price, traditional, management contracting, construction management-at-risk, design & build and design-build bridging.

Residential construction practices, technologies, and resources must conform to local building authority regulations and codes of practice. Materials readily available in the area generally dictate the construction materials used (e.g. brick versus stone, versus timber). Cost of construction on a per square meter (or per square foot) basis for houses can vary dramatically based on site conditions, local regulations, economies of scale (custom designed homes are often more expensive to build) and the availability of skilled tradesmen. Residential construction as well as other types of construction can generate waste such that planning is required.

According to McKinsey research, productivity growth per worker in construction has lagged behind many other industries across different countries including in the United States and in European countries. In the United States, construction productivity per worker has declined by half since the 1960s.[13]

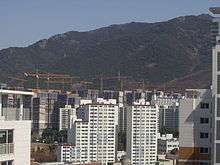

Residential construction

.jpg)

The most popular method of residential construction in North America is wood-framed construction. Typical construction steps for a single-family or small multi-family house are:

- Obtain an engineered soil test of lot where construction is planned. From an engineer or company specializing in soil testing.

- Develop floor plans and obtain a materials list for estimations (more recently performed with estimating software)

- Obtain structural engineered plans for foundation and structure. To be completed by either a licensed engineer or architect. To include both a foundation and framing plan.

- Obtain lot survey

- Obtain government building approval if necessary

- If required obtain approval from HOA (homeowners association) or ARC (architectural review committee)

- Clear the building site (demolition of existing home if necessary)

- Survey to stake out for the foundation

- Excavate the foundation and dig footers (Scope of work is dependent of foundation designed by engineer)

- Install plumbing grounds

- Pour a foundation and footers with concrete

- Build the main load-bearing structure out of thick pieces of wood and possibly metal I-beams for large spans with few supports. See framing (construction)

- Add floor and ceiling joists and install subfloor panels

- Cover outer walls and roof in OSB or plywood and a water-resistive barrier.

- Install roof shingles or other covering for flat roof

- Cover the walls with siding, typically vinyl, wood, or brick veneer but possibly stone or other materials

- Install windows

- Frame interior walls with wooden 2×4s

- Add internal plumbing, HVAC, electrical, and natural gas utilities

- Building inspector visits if necessary to approve utilities and framing

- Install insulation and interior drywall panels (cementboard for wet areas) and to complete walls and ceilings

- Install bathroom fixtures

- Spackle, prime, and paint interior walls and ceilings

- Additional tiling on top of cementboard for wet areas, such as the bathroom and kitchen backsplash

- Installation of final floor covering, such as floor tile, carpet, or wood flooring

- Installation of major appliances

- Unless the original owners are building the house, at this point it is typically sold or rented.

Processes

Design team

In the industrialized world, construction usually involves the translation of designs into reality. A formal design team may be assembled to plan the physical proceedings, and to integrate those proceedings with the other parts. The design usually consists of drawings and specifications, usually prepared by a design team including architect, civil engineers, mechanical engineers, electrical engineers, structural engineers, fire protection engineers, planning consultants, architectural consultants, and archaeological consultants. The design team is most commonly employed by (i.e. in contract with) the property owner. Under this system, once the design is completed by the design team, a number of construction companies or construction management companies may then be asked to make a bid for the work, either based directly on the design, or on the basis of drawings and a bill of quantities provided by a quantity surveyor. Following evaluation of bids, the owner typically awards a contract to the most cost efficient bidder.

The best modern trend in design is toward integration of previously separated specialties, especially among large firms. In the past, architects, interior designers, engineers, developers, construction managers, and general contractors were more likely to be entirely separate companies, even in the larger firms. Presently, a firm that is nominally an "architecture" or "construction management" firm may have experts from all related fields as employees, or to have an associated company that provides each necessary skill. Thus, each such firm may offer itself as "one-stop shopping" for a construction project, from beginning to end. This is designated as a "design build" contract where the contractor is given a performance specification and must undertake the project from design to construction, while adhering to the performance specifications.[14]

Several project structures can assist the owner in this integration, including design-build, partnering and construction management. In general, each of these project structures allows the owner to integrate the services of architects, interior designers, engineers and constructors throughout design and construction. In response, many companies are growing beyond traditional offerings of design or construction services alone and are placing more emphasis on establishing relationships with other necessary participants through the design-build process.

The increasing complexity of construction projects creates the need for design professionals trained in all phases of the project's life-cycle and develop an appreciation of the building as an advanced technological system requiring close integration of many sub-systems and their individual components, including sustainability. Building engineering is an emerging discipline that attempts to meet this new challenge.

Financial advisors

Construction projects can suffer from preventable financial problems. Underbids happen when builders ask for too little money to complete the project. Cash flow problems exist when the present amount of funding cannot cover the current costs for labour and materials, and because they are a matter of having sufficient funds at a specific time, can arise even when the overall total is enough. Fraud is a problem in many fields, but is notoriously prevalent in the construction field.[15] Financial planning for the project is intended to ensure that a solid plan with adequate safeguards and contingency plans are in place before the project is started and is required to ensure that the plan is properly executed over the life of the project.

Mortgage bankers, accountants, and cost engineers are likely participants in creating an overall plan for the financial management of the building construction project. The presence of the mortgage banker is highly likely, even in relatively small projects since the owner's equity in the property is the most obvious source of funding for a building project. Accountants act to study the expected monetary flow over the life of the project and to monitor the payouts throughout the process. Cost engineers and estimators apply expertise to relate the work and materials involved to a proper valuation. Cost overruns with government projects have occurred when the contractor identified change orders or project changes that increased costs, which are not subject to competition from other firms as they have already been eliminated from consideration after the initial bid.[16]

Large projects can involve highly complex financial plans and often start with a conceptual estimate performed by a building estimator. As portions of a project are completed, they may be sold, supplanting one lender or owner for another, while the logistical requirements of having the right trades and materials available for each stage of the building construction project carries forward. In many English-speaking countries, but not the United States, projects typically use quantity surveyors.

Legal aspects

A construction project must fit into the legal framework governing the property. These include governmental regulations on the use of property, and obligations that are created in the process of construction.

When applicable, the project must adhere to zoning and building code requirements. Constructing a project that fails to adhere to codes does not benefit the owner. Some legal requirements come from malum in se considerations, or the desire to prevent indisputably bad phenomena, e.g. explosions or bridge collapses. Other legal requirements come from malum prohibitum considerations, or factors that are a matter of custom or expectation, such as isolating businesses from a business district or residences from a residential district. An attorney may seek changes or exemptions in the law that governs the land where the building will be built, either by arguing that a rule is inapplicable (the bridge design will not cause a collapse), or that the custom is no longer needed (acceptance of live-work spaces has grown in the community).[17]

A construction project is a complex net of contracts and other legal obligations, each of which all parties must carefully consider. A contract is the exchange of a set of obligations between two or more parties, but it is not so simple a matter as trying to get the other side to agree to as much as possible in exchange for as little as possible. The time element in construction means that a delay costs money, and in cases of bottlenecks, the delay can be extremely expensive. Thus, the contracts must be designed to ensure that each side is capable of performing the obligations set out. Contracts that set out clear expectations and clear paths to accomplishing those expectations are far more likely to result in the project flowing smoothly, whereas poorly drafted contracts lead to confusion and collapse.

Legal advisors in the beginning of a construction project seek to identify ambiguities and other potential sources of trouble in the contract structure, and to present options for preventing problems. Throughout the process of the project, they work to avoid and resolve conflicts that arise. In each case, the lawyer facilitates an exchange of obligations that matches the reality of the project.

Interaction of expertise

Design, finance, and legal aspects overlap and interrelate. The design must be not only structurally sound and appropriate for the use and location, but must also be financially possible to build, and legal to use. The financial structure must accommodate the need for building the design provided, and must pay amounts that are legally owed. The legal structure must integrate the design into the surrounding legal framework, and enforce the financial consequences of the construction process.

Procurement

Procurement describes the merging of activities undertaken by the client to obtain a building. There are many different methods of construction procurement; however, the three most common types of procurement are traditional (design–bid–build), design-build and management contracting.[18]

There is also a growing number of new forms of procurement that involve relationship contracting where the emphasis is on a co-operative relationship among the principal, the contractor, and other stakeholders within a construction project. New forms include partnering such as Public-Private Partnering (PPPs) aka private finance initiatives (PFIs) and alliances such as "pure" or "project" alliances and "impure" or "strategic" alliances. The focus on co-operation is to ameliorate the many problems that arise from the often highly competitive and adversarial practices within the construction industry.

Traditional

This is the most common method of construction procurement, and it is well-established and recognized. In this arrangement, the architect or engineer acts as the project coordinator. His or her role is to design the works, prepare the specifications and produce construction drawings, administer the contract, tender the works, and manage the works from inception to completion. There are direct contractual links between the architect's client and the main contractor. Any subcontractor has a direct contractual relationship with the main contractor. The procedure continues until the building is ready to occupy.

Design-build

Havelock City Project, Sri Lanka

This approach has become more common in recent years, and also involves the client contracting a single entity that both provides a design and builds it. In some cases, the design-build package can also include finding the site, arranging funding and applying for all necessary statutory consents.

The owner produces a list of requirements for a project, giving an overall view of the project's goals. Several D&B contractors present different ideas about how to accomplish these goals. The owner selects the ideas they like best and hires the appropriate contractor. Often, it is not just one contractor, but a consortium of several contractors working together. Once these have been hired, they begin building the first phase of the project. As they build phase 1, they design phase 2. This is in contrast to a design-bid-build contract, where the project is completely designed by the owner, then bid on, then completed.

Kent Hansen pointed out that state departments of transportation usually use design build contracts as a way of progressing projects when states lack the skills-resources. In such departments, design build contracts are usually employed for very large projects.[19]

Management procurement systems

In this arrangement the client plays an active role in the procurement system by entering into separate contracts with the designer (architect or engineer), the construction manager, and individual trade contractors. The client takes on the contractual role, while the construction or project manager provides the active role of managing the separate trade contracts, and ensuring that they complete all work smoothly and effectively together.

Management procurement systems are often used to speed up the procurement processes, allow the client greater flexibility in design variation throughout the contract, give the ability to appoint individual work contractors, separate contractual responsibility on each individual throughout the contract, and to provide greater client control.

In recent time, construction software starts to get traction—as it digitizes construction industry. Among solutions, there are for example: Procore, GenieBelt, PlanGrid, bouw7, etc.

Sustainability in construction

Sustainability during the construction phase is one of the aspects of “green building," defined by the United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) as "the practice of creating structures and using processes that are environmentally responsible and resource-efficient throughout a building's life-cycle from siting to design, construction, operation, maintenance, renovation and deconstruction."[20]

Authority having jurisdiction

In construction, the authority having jurisdiction (AHJ) is the governmental agency or sub-agency that regulates the construction process. In most cases, this is the municipality where the building is located. However, construction performed for supra-municipal authorities are usually regulated directly by the owning authority, which becomes the AHJ.

Before the foundation can be dug, contractors are typically required to verify and have existing utility lines marked, either by the utilities themselves or through a company specializing in such services. This lessens the likelihood of damage to the existing electrical, water, sewage, phone, and cable facilities, which could cause outages and potentially hazardous situations. During the construction of a building, the municipal building inspector inspects the building periodically to ensure that the construction adheres to the approved plans and the local building code. Once construction is complete and a final inspection has been passed, an occupancy permit may be issued.

An operating building must remain in compliance with the fire code. The fire code is enforced by the local fire department or a municipal code enforcement office.

Changes made to a building that affect safety, including its use, expansion, structural integrity, and fire protection items, usually require approval of the AHJ for review concerning the building code.

Industry characteristics

In the United States, the industry in 2014 has around $960 billion in annual revenue according to statistics tracked by the Census Bureau, of which $680 billion is private (split evenly between residential and nonresidential) and the remainder is government.[21] In 2005, there were about 667,000 firms employing 1 million contractors (200,000 general contractors, 38,000 heavy, and 432,000 specialty); the average contractor employed fewer than 10 employees.[22] As a whole, the industry employed an estimated 5.8 million in April 2013, with a 13.2% unemployment rate.[23] In the United States, approximately 828,000 women were employed in the construction industry as of 2011.[24]

Careers

There are many routes to the different careers within the construction industry. These three main tiers are based on educational background and training, which vary by country:

- Unskilled and semi-skilled – General site labor with little or no construction qualifications.

- Skilled – Tradesmen who've served apprenticeships, typically in labor unions, and on-site managers who possess extensive knowledge and experience in their craft or profession.

- Technical and management – Personnel with the greatest educational qualifications, usually graduate degrees, trained to design, manage and instruct the construction process.

Skilled occupations include carpenters, electricians, plumbers, ironworkers, masons, and many other manual crafts, as well as those involved in project management. In the UK these require further education qualifications, often in vocational subject areas. These qualifications are either obtained directly after the completion of compulsory education or through "on the job" apprenticeship training.[25] In the UK, 8500 construction-related apprenticeships were commenced in 2007.[26]

Technical and specialized occupations require more training as a greater technical knowledge is required. These professions also hold more legal responsibility. A short list of the main careers with an outline of the educational requirements are given below:

- Architect – Typically holds 1, undergraduate 3-year degree in architecture + 1, post-graduate 2-year degree (DipArch or BArch) in architecture plus 24 months' experience within the industry. To use the title "architect" the individual must be registered on the Architects Registration Board register of Architects.

- Civil engineer – Typically holds a degree in a related subject. The Chartered Engineer qualification is controlled by the Engineering Council, and is often achieved through membership of the Institution of Civil Engineers. A new university graduate must hold a master's degree to become chartered; persons with bachelor's degrees may become an Incorporated Engineer.

- Building services engineer – Often referred to as an "M&E Engineer" typically holds a degree in mechanical or electrical engineering. Chartered Engineer status is governed by the Engineering Council, mainly through the Chartered Institution of Building Services Engineers.

- Project manager – Typically holds a 4-year or greater higher education qualification, but are often also qualified in another field such as architecture, civil engineering or quantity surveying.

- Structural engineer – Typically holds a bachelor's or master's degree in structural engineering. A P.ENG is required from the Professional Engineers Ontario (Canada). New university graduates must hold a master's degree to gain chartered status from the Engineering Council, mainly through the Institution of Structural Engineers (UK).

- Quantity surveyor – Typically holds a bachelor's degree in quantity surveying. Chartered status is gained from the Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors.

- Civil estimators are professionals who typically have a background in civil engineering, construction project management, or construction supervision.

In 2010 a salary survey revealed the differences in remuneration between different roles, sectors and locations in the construction and built environment industry.[27] The results showed that areas of particularly strong growth in the construction industry, such as the Middle East, yield higher average salaries than in the UK, for example. The average earning for a professional in the construction industry in the Middle East, across all sectors, job types and levels of experience, is £42,090, compared to £26,719 in the UK.[28] This trend is not necessarily due to the fact that more affluent roles are available; however, as architects with 14 or more years' experience working in the Middle East earn on average £43,389 per annum, compared to £40,000 in the UK.[28] Some construction workers in the US/Canada have made more than $100,000 annually, depending on their trade.[29]

Safety

Construction is one of the most dangerous occupations in the world, incurring more occupational fatalities than any other sector in both the United States and in the European Union.[30][31] In 2009, the fatal occupational injury rate among construction workers in the United States was nearly three times that for all workers, with Falls being one of the most common causes of fatal and non-fatal injuries among construction workers.[30] Proper safety equipment such as harnesses, hard hats and guardrails and procedures such as securing ladders and inspecting scaffolding can curtail the risk of occupational injuries in the construction industry.[32] Other major causes of fatalities in the construction industry include electrocution, transportation accidents, and trench cave-ins.[33]

Other safety risks for workers in construction include hearing loss due to high noise exposure, musculoskeletal injury, chemical exposure, and high levels of stress.[24] Besides that, the high turnover of workers in construction industry imposes a huge challenge of accomplishing the restructuring of work practices in individual workplaces or with individual workers. Construction has been identified by the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) as a priority industry sector in the National Occupational Research Agenda (NORA) to identify and provide intervention strategies regarding occupational health and safety issues.[34][35]

History

The first huts and shelters were constructed by hand or with simple tools. As cities grew during the Bronze Age, a class of professional craftsmen, like bricklayers and carpenters, appeared. Occasionally, slaves were used for construction work. In the Middle Ages, the artisan craftsmen were organized into guilds. In the 19th century, steam-powered machinery appeared, and, later, diesel- and electric-powered vehicles such as cranes, excavators and bulldozers.

Fast-track construction has been increasingly popular in the 21st century. Some estimates suggest that 40% of construction projects are now fast-track construction.[36]

Construction output by country

| Economy | Construction output in 2015 (billions in USD) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (01) |

1,849 | ||||||||

| (02) |

599 | ||||||||

| (03) |

569 | ||||||||

| (04) |

333 | ||||||||

| (05) |

147 | ||||||||

| (06) |

143 | ||||||||

| (07) |

131 | ||||||||

| (08) |

131 | ||||||||

| (09) |

115 | ||||||||

| (10) |

111 | ||||||||

| (11) |

109 | ||||||||

| (12) |

107 | ||||||||

| (13) |

104 | ||||||||

| (14) |

93 | ||||||||

| (15) |

92 | ||||||||

| (16) |

58 | ||||||||

| (17) |

35 | ||||||||

| (18) |

34 | ||||||||

| (19) |

34 | ||||||||

| (20) |

34 | ||||||||

| (21) |

34 | ||||||||

| (22) |

33 | ||||||||

| (23) |

32 | ||||||||

| (24) |

29 | ||||||||

| (25) |

29 | ||||||||

|

The twenty-five largest countries in the world by construction output (2012)[37] | |||||||||

See also

| Look up construction in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- Agile construction

- Index of construction articles

- List of construction trades

- Outline of construction

- Real estate development

- Site analysis

- Site survey

- Structural robustness

- Umarell

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Construction. |

| Library resources about Construction |

- Compare: "Construction", Merriam-Webster.com, Merriam-Webster, retrieved 2016-02-16,

[...] the act or process of building something (such as a house or road) [...].

- Halpin, Daniel W.; Senior, Bolivar A. (2010), Construction Management (4 ed.), Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, p. 9, ISBN 9780470447239, retrieved May 16, 2015

- Chitkara, K. K. (1998), Construction Project Management, New Delhi: Tata McGraw-Hill Education, p. 4, ISBN 9780074620625, retrieved May 16, 2015

- "Construction" def. 1.a. 1.b. and 1.c. Oxford English Dictionary Second Edition on CD-ROM (v. 4.0) Oxford University Press 2009

- "Construction". Online Etymology Dictionary http://www.etymonline.com/index.php?term=construction accessed 3/6/2014

- Chitkara, pp. 9–10.

- Halpin, pp. 15–16.

- "The Top 250", Engineering News-Record, September 1, 2014

- "The Top 400" (PDF), Engineering News-Record, May 26, 2014

- US Census Bureau,NAICS Search 2012 NAICS Definition, Sector 23 – Construction

- US Department of Labor (OSHA), Division C: Construction

- "The Subaru Headquarters Construction Site", Engineering News-Record, October 20, 2016

- "The construction industry's productivity problem". The Economist. Retrieved 2017-08-21.

- Dynybyl, Vojtěch; Berka, Ondrej; Petr, Karel; Lopot, František; Dub, Martin (2015-12-09). The Latest Methods of Construction Design. Springer. ISBN 9783319227627.

- "Global construction industry faces growing threat of economic crime". pwc. pwc. Retrieved 16 September 2015.

- "North County News – San Diego Union Tribune". www.nctimes.com.

- Mason, Jim (2016-04-14). Construction Law: From Beginner to Practitioner. Routledge. ISBN 9781317391777.

- Mosey, David (2019-05-20). Collaborative Construction Procurement and Improved Value. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 9781119151913.

- Cronin, Jeff (2005). "S. Carolina Court to Decide Legality of Design-Build Bids". Construction Equipment Guide. Retrieved 2008-01-04.

- "Basic Information | Green Building |US EPA". archive.epa.gov. Retrieved 2018-12-11.

- Value of Construction Put in Place at a Glance. United States Census Bureau. Also see Manufacturing & Construction Statistics for more information.

- McIntyre M, Strischek D. (2005). Surety Bonding in Today's Construction Market: Changing Times for Contractors, Bankers, and Sureties. The RMA Journal.

- Industries at a Glance: Construction: NAICS 23. U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

- Swanson, Naomi; Tisdale-Pardi, Julie; MacDonald, Leslie; Tiesman, Hope M. (13 May 2013). "Women's Health at Work". National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. Retrieved 21 January 2015.

- Wood, Hannah (17 January 2012). "UK Construction Careers, Certifications/Degrees and occupations". TH Services. Archived from the original on 4 March 2012. Retrieved 4 March 2012.

- "CITB Apprenticeships - CITB". www.cskills.org.

- "UK website launches salary comparison tool". Retrieved 2011-07-04.

- "Salary Benchmarker". Retrieved 2011-07-04.

- Fottrell, Quentin. "5 blue-collar jobs that pay $100,000 a year". MarketWatch. Retrieved 2019-04-21.

- "Construction Safety and Health". Workplace Safety & Health Topics. National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health. Retrieved 3 August 2012.

- "Health and safety at work statistics". eurostat. European Commission. Retrieved 3 August 2012.

- "OSHA's Fall Prevention Campaign". Occupational Safety and Health Administration. Retrieved 6 August 2012.

- "The Construction Chart Book: The US Construction Industry and its Workers" (PDF). CPWR, 2013.

- "CDC - NIOSH Program Portfolio : Construction Program". www.cdc.gov. 2018-04-05. Retrieved 2018-04-07.

- "CDC - NIOSH - NORA Construction Sector Council". www.cdc.gov. 2017-12-01. Retrieved 2018-04-07.

- Knecht B. Fast-track construction becomes the norm. Architectural Record.

- Figures from the United Nations' UN National Accounts Database. for the countries of the world. Retrieved 1 February 2014.