Common cuckoo

The common cuckoo (Cuculus canorus) is a member of the cuckoo order of birds, Cuculiformes, which includes the roadrunners, the anis and the coucals.

| Common cuckoo | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Cuculiformes |

| Family: | Cuculidae |

| Genus: | Cuculus |

| Species: | C. canorus |

| Binomial name | |

| Cuculus canorus | |

| |

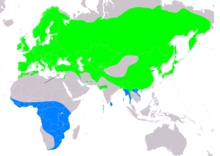

| Range of Cuculus canorus Breeding Passage Non-breeding Possibly Extant (breeding) | |

This species is a widespread summer migrant to Europe and Asia, and winters in Africa. It is a brood parasite, which means it lays eggs in the nests of other bird species, particularly of dunnocks, meadow pipits, and reed warblers. Although its eggs are larger than those of its hosts, the eggs in each type of host nest resemble the host's eggs. The adult too is a mimic, in its case of the sparrowhawk; since that species is a predator, the mimicry gives the female time to lay her eggs without being seen to do so.

Taxonomy

The species' binomial name is derived from the Latin cuculus (the cuckoo) and canorus (melodious; from canere, meaning to sing).[2][3] The cuckoo family gets its common name and genus name by onomatopoeia for the call of the male common cuckoo.[4] The English word "cuckoo" comes from the Old French cucu, and its earliest recorded usage in English is from around 1240, in the song Sumer Is Icumen In. The song is written in Middle English, and the first two lines are: "Svmer is icumen in / Lhude sing cuccu." In modern English, this translates to "Summer has come in / Loudly sing, Cuckoo!".[5]

There are four subspecies worldwide:[6]

- C. c. canorus, the nominate subspecies, was first described by Linnaeus in 1758. It occurs from Ireland through Scandinavia, northern Russia and Siberia to Japan in the east, and from the Pyrenees through Turkey, Kazakhstan, Mongolia, northern China and Korea. It winters in Africa and South Asia.

- C. c. bakeri, first described by Hartert in 1912, breeds in western China to the Himalayan foothills in northern India, Nepal, Myanmar, northwestern Thailand and southern China. During the winter it is found in Assam, East Bengal and southeastern Asia.

- C. c. bangsi was first described by Oberholser in 1919 and breeds in Iberia, the Balearic Islands and North Africa, spending the winter in Africa.

- C. c. subtelephonus, first described by Zarudny in 1914, breeds in Central Asia from Turkestan to southern Mongolia. It migrates to southern Asia and Africa for the winter.

Lifespan and demography

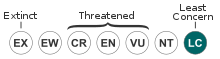

Although the common cuckoo's global population appears to be declining, it is classified of being of Least Concern by the International Union for Conservation of Nature. It is estimated that the species numbers between 25 million and 100 million individuals worldwide, with around 12.6 million to 25.8 million of those birds breeding in Europe.[1] The maximum recorded lifespan of a common cuckoo in the United Kingdom is 6 years, 11 months and 2 days.[2]

Description

The common cuckoo is 32–34 centimetres (13–13 in) long from bill to tail (with a tail of 13–15 centimetres (5.1–5.9 in) and a wingspan of 55–60 centimetres (22–24 in).[4] The legs are short.[7] It has a greyish, slender body and long tail, similar to a sparrowhawk in flight, where the wingbeats are regular. During the breeding season, common cuckoos often settle on an open perch with drooped wings and raised tail.[7] There is a rufous colour morph, which occurs occasionally in adult females but more often in juveniles.[4]

All adult males are slate-grey; the grey throat extends well down the bird's breast with a sharp demarcation to the barred underparts.[8] The iris, orbital ring, the base of the bill and feet are yellow.[7] Grey adult females have a pinkish-buff or buff background to the barring and neck sides, and sometimes small rufous spots on the median and greater coverts and the outer webs of the secondary feathers.[8]

Rufous morph adult females have reddish-brown upperparts with dark grey or black bars. The black upperpart bars are narrower than the rufous bars, as opposed to rufous juvenile birds, where the black bars are broader.[8]

Common cuckoos in their first autumn have variable plumage. Some have strongly-barred chestnut-brown upperparts, while others are plain grey. Rufous-brown birds have heavily barred upperparts with some feathers edged with creamy-white. All have whitish edges to the upper wing-coverts and primaries. The secondaries and greater coverts have chestnut bars or spots. In spring, birds hatched in the previous year may retain some barred secondaries and wing-coverts.[8] The most obvious identification features of juvenile common cuckoos are the white nape patch and white feather fringes.[7]

Common cuckoos moult twice a year: a partial moult in summer and a complete moult in winter.[8] Males weigh around 130 grams (4.6 oz) and females 110 grams (3.9 oz).[2] The common cuckoo looks very similar to the Oriental cuckoo, which is slightly shorter-winged on average.[8]

Mimicry in adult

A study using stuffed bird models found that small birds are less likely to approach common cuckoos that have barred underparts similar to the Eurasian sparrowhawk, a predatory bird. Eurasian reed warblers were found more aggressive to cuckoos that looked less hawk-like, meaning that the resemblance to the hawk helps the cuckoo to access the nests of potential hosts.[9] Other small birds, great tits and blue tits, showed alarm and avoided attending feeders on seeing either (mounted) sparrowhawks or cuckoos; this implies that the cuckoo's hawklike appearance functions as protective mimicry, whether to reduce attacks by hawks or to make brood parasitism easier.[10]

Hosts attack cuckoos more when they see neighbors mobbing cuckoos.[11] The existence of the two plumage morphs in females may be due to frequency-dependent selection if this learning applies only to the morph that hosts see neighbors mob. In an experiment with dummy cuckoos of each morph and a sparrowhawk, reed warblers were more likely to attack both cuckoo morphs than the sparrowhawk, and even more likely to mob a certain cuckoo morph when they saw neighbors mobbing that morph, decreasing the reproductive success of that morph and selecting for the less common morph.[11]

Voice

The male's song, goo-ko, is usually given from an open perch. During the breeding season the male typically gives this vocalisation with intervals of 1–1.5 seconds, in groups of 10–20 with a rest of a few seconds between groups. The female has a loud bubbling call.[4] The song starts as a descending minor third early in the year in April, and the interval gets wider, through a major third to a fourth as the season progresses, and in June the cuckoo "forgets its tune" and may make other calls such as ascending intervals. The wings are drooped when calling intensely and when in the vicinity of a potential female, the male often wags its tail from side to side or the body may pivot from side to side.[12]

Distribution and habitat

Essentially a bird of open land, the common cuckoo is a widespread summer migrant to Europe and Asia, and winters in Africa. Birds arrive in Europe in April and leave in September.[7] The common cuckoo has also occurred as a vagrant in countries including Barbados, the United States, Greenland, the Faroe Islands, Iceland, Indonesia, Palau, Seychelles, Taiwan and China.[1] Between 1995 and 2015, the distribution of cuckoos within the UK has shifted towards the north, with a decline by 69% in England but an increase by 33% in Scotland.[13]

Behaviour

Food and feeding

The common cuckoo's diet consists of insects, with hairy caterpillars, which are distasteful to many birds, being a specialty of preference.[14] It also occasionally eats eggs and chicks.[15]

Breeding

The common cuckoo is an obligate brood parasite; it lays its eggs in the nests of other birds. At the appropriate moment, the hen cuckoo flies down to the host's nest, pushes one egg out of the nest, lays an egg and flies off. The whole process takes about 10 seconds. A female may visit up to 50 nests during a breeding season. Common cuckoos first breed at the age of two years.[2]

Egg mimicry

More than 100 host species have been recorded: meadow pipit, dunnock and Eurasian reed warbler are the most common hosts in northern Europe; garden warbler, meadow pipit, pied wagtail and European robin in central Europe; brambling and common redstart in Finland; and great reed warbler in Hungary.[4]

Female common cuckoos are divided into gentes – groups of females favouring a particular host species' nest and laying eggs that match those of that species in color and pattern. Evidence from mitochondrial DNA analyses suggest that each gene may have multiple independent origins due to parasitism of specific hosts by different ancestors.[16] One hypothesis for the inheritance of egg appearance mimicry is that this trait is inherited from the female only, suggesting that it is carried on the sex-determining W chromosome (females are WZ, males ZZ). A genetic analysis of gentes supports this proposal by finding significant differentiation in mitochondrial DNA, but not in microsatellite DNA.[16] A second proposal for the inheritance of this trait is that the genes controlling egg characteristics are carried on autosomes rather than just the W chromosome. Another genetic analysis of sympatric gentes supports this second proposal by finding significant genetic differentiation in both microsatellite DNA and mitochondrial DNA.[17] Considering the tendency for common cuckoo males to mate with multiple females and produce offspring raised by more than one host species, it appears as though males do not contribute to the maintenance of common cuckoo gentes. However, it was found that only nine percent of offspring were raised outside of their father's presumed host species.[17] Therefore, both males and females may contribute to the maintenance of common cuckoo egg mimicry polymorphism.[16][17] It is notable that most non-parasitic cuckoo species lay white eggs, like most non-passerines other than ground-nesters.

As the common cuckoo evolves to lay eggs that better imitate the host's eggs, the host species adapts and is more able to distinguish the cuckoo egg. A study of 248 common cuckoo and host eggs demonstrated that female cuckoos that parasitised common redstart nests laid eggs that matched better than those that targeted dunnocks. Spectroscopy was used to model how the host species saw the cuckoo eggs. Cuckoos that target dunnock nests lay white, brown-speckled eggs, in contrast to the dunnock's own blue eggs. The theory suggests that common redstarts have been parasitised by common cuckoos for longer, and so have evolved to be better than the dunnocks at noticing the cuckoo eggs. The cuckoo, over time, has needed to evolve more accurate mimicking eggs to successfully parasitise the redstart. In contrast, cuckoos do not seem to have experienced evolutionary pressure to develop eggs which closely mimic the dunnock's, as dunnocks do not seem to be able to distinguish between the two species' eggs, despite the significant colour differences. The dunnock's inability to distinguish the eggs suggests that they have not been parasitised for very long, and have not yet evolved defences against it, unlike the redstart.[18]

Studies performed on great reed warbler nests in central Hungary, showed an "unusually high" frequency of common cuckoo parasitism, with 64% of the nests parasitised. Of the nests targeted by cuckoos, 64% contained one cuckoo egg, 23% had two, 10% had three and 3% had four common cuckoo eggs. In total, 58% of the common cuckoo eggs were laid in nests that were multiply parasitised. When laying eggs in nests already parasitised, the female cuckoos removed one egg at random, showing no discrimination between the great reed warbler eggs and those of other cuckoos.[19]

It was found that nests close to cuckoo perches were most vulnerable: multiple parasitised nests were closest to the vantage points, and unparasitised nests were farthest away. Nearly all the nests "in close vicinity" to the vantage points were parasitised. More visible nests were more likely to be selected by the common cuckoos. Female cuckoos use their vantage points to watch for potential hosts and find it easier to locate the more visible nests while they are egg-laying,[20] however, novel studies highlight that host alarm calls might also play an important role during nest searching.[21]

The great reed warblers' responses to the common cuckoo eggs varied: 66% accepted the egg(s); 12% ejected them; 20% abandoned the nests entirely; 2% buried the eggs. 28% of the cuckoo eggs were described as "almost perfect" in their mimesis of the host eggs, and the warblers rejected "poorly mimetic" cuckoo eggs more often. The degree of mimicry made it difficult for both the great reed warblers and the observers to tell the eggs apart.[19]

The egg measures 22 by 16 millimetres (0.87 in × 0.63 in) and weighs 3.2 grams (0.11 oz), of which 7% is shell.[2] Research has shown that the female common cuckoo is able to keep its egg inside its body for an extra 24 hours before laying it in a host's nest. This means the cuckoo chick can hatch before the host's chicks do, and it can eject the unhatched eggs from the nest. Scientists incubated common cuckoo eggs for 24 hours at the bird's body temperature of 40 °C (104 °F), and examined the embryos, which were found "much more advanced" than those of other species studied. The idea of 'internal incubation' was first put forward in 1802 and 18th and 19th Century egg collectors had reported finding that cuckoo embryos were more advanced than those of the host species.[22]

- Yellow-bellied warbler (Abroscopus superciliaris)

- Common linnet (Acanthis cannabina)

- Common redpoll (Acanthis flammea)

- Paddyfield warbler (Acrocephalus agricola)

- Moustached warbler (Acrocephalus melanopogon)

- Great reed warbler (Acrocephalus arundinaceus)

- Black-browed reed warbler (Acrocephalus bistrigiceps)

- Blyth's reed warbler (Acrocephalus dumetorum)

- Aquatic warbler (Acrocephalus paludicola)

- Marsh warbler (Acrocephalus palustris)

- Sedge warbler (Acrocephalus schoenobaenus)

- Eurasian reed warbler (Acrocephalus scirpaceus)

- Clamorous reed warbler (Acrocephalus stentoreus)

- Rusty-fronted barwing (Actinodura egertoni)

- Long-tailed tit (Aegithalos caudatus)

- Eurasian skylark (Alauda arvensis)

- Dusky fulvetta (Alcippe brunnea)

- Rufous-winged fulvetta (Alcippe castaneceps)

- Yellow-throated fulvetta (Alcippe cinerea)

- Nepal fulvetta (Alcippe nipalensis)

- Brown-cheeked fulvetta (Alcippe poioicephala)

- Tawny pipit (Anthus campestris)

- Red-throated pipit (Anthus cervinus)

- Blyth's pipit (Anthus godlewskii)

- Olive-backed pipit (Anthus hodgsoni)

- Australasian pipit (Anthus novaeseelandiae)

- Meadow pipit (Anthus pratensis)

- Rosy pipit (Anthus roseatus)

- Buff-bellied pipit (Anthus rubescens)

- Water pipit (Anthus spinoletta)

- Upland pipit (Anthus sylvanus)

- Tree pipit (Anthus trivialis)

- Little spiderhunter (Arachnothera longirostris)

- Streaked spiderhunter (Arachnothera magna)

- Lesser shortwing (Brachypteryx leucophrys)

- White-browed shortwing (Brachypteryx montana)

- Red-capped lark (Calandrella cinerea)

- Lapland longspur (Calcarius lapponicus)

- Carduelis caniceps[24]

- European goldfinch (Carduelis carduelis)

- Twite (Carduelis flavirostris)

- Common rosefinch (Carpodacus erythrinus)

- Pallas's rosefinch (Carpodacus roseus)

- Short-toed treecreeper (Certhia brachydactyla)

- Eurasian treecreeper (Certhia familiaris)

- Cetti's warbler (Cettia cetti)

- Brown-flanked bush warbler (Cettia fortipes)

- Rufous-tailed scrub robin (Cercotrichas galactotes)

- European greenfinch (Chloris chloris)

- Grey-capped greenfinch (Chloris sinica)

- Golden-fronted leafbird (Chloropsis aurifrons)

- Orange-bellied leafbird (Chloropsis hardwickii)

- Brown dipper (Cinclus pallasii)

- Zitting cisticola (Cisticola juncidis)

- Golden-headed cisticola (Cisticola exilis)

- Hawfinch (Coccothraustes coccothraustes)

- Purple cochoa (Cochoa purpurea)

- Green cochoa (Cochoa viridis)

- White-rumped shama (Copsychus malabaricus)

- Oriental magpie-robin (Copsychus saularis)

- Black-winged cuckooshrike (Coracina melaschistos)

- Grey-headed canary-flycatcher (Culicicapa ceylonensis)

- Azure-winged magpie (Cyanopica cyanus)

- Blue-and-white flycatcher (Cyanoptila cyanomelana)

- Blue-throated blue flycatcher (Cyornis rubeculoides)

- Common house martin (Delichon urbica)

- Bronzed drongo (Dicrurus aeneus)

- Ashy drongo (Dicrurus leucophaeus)

- Yellow-breasted bunting (Emberiza aureola)

- Red-headed bunting (Emberiza bruniceps)

- Corn bunting (Emberiza calandra)

- Yellow-browed bunting (Emberiza chrysophrys)

- Rock bunting (Emberiza cia)

- Meadow bunting (Emberiza cioides)

- Cirl bunting (Emberiza cirlus)

- Yellowhammer (Emberiza citrinella)

- Yellow-throated bunting (Emberiza elegans)

- Chestnut-eared bunting (Emberiza fucata)

- Ortolan bunting (Emberiza hortulana)

- Emberiza icterica[25]

- Black-headed bunting (Emberiza melanocephala)

- Little bunting (Emberiza pusilla)

- Rustic bunting (Emberiza rustica)

- Chestnut bunting (Emberiza rutila)

- Common reed bunting (Emberiza schoeniclus)

- Black-faced bunting (Emberiza spodocephala)

- Tristram's bunting (Emberiza tristrami)

- Black-backed forktail (Enicurus immaculatus)

- Spotted forktail (Enicurus maculatus)

- Slaty-backed forktail (Enicurus schistaceus)

- European robin (Erithacus rubecula)

- Horned lark (Eremophila alpestris)

- Japanese grosbeak (Eophona personata)

- Slaty-backed flycatcher (Ficedula hodgsonii)

- European pied flycatcher (Ficedula hypoleuca)

- Narcissus flycatcher (Ficedula narcissina)

- Red-breasted flycatcher (Ficedula parva)

- Ultramarine flycatcher (Ficedula superciliaris)

- Slaty-blue flycatcher (Ficedula tricolor)

- Common chaffinch (Fringilla coelebs)

- Brambling (Fringilla montifringilla)

- Crested lark (Galerida cristata)

- Streaked laughingthrush (Garrulax lineatus)

- Ashy bulbul (Hemixos flavala)

- Rufous-backed sibia (Heterophasia annectans)

- Grey sibia (Heterophasia gracilis)

- Booted warbler (Iduna caligata)

- Icterine warbler (Hippolais icterina)

- Eastern olivaceous warbler (Hippolais pallida)

- Melodious warbler (Hippolais polyglotta)

- Sykes's warbler (Iduna rama)

- Barn swallow (Hirundo rustica)

- Black-naped monarch (Hypothymis azurea)

- Malagasy bulbul (Hypsipetes madagascariensis)

- Mountain bulbul (Ixos mcclellandi)

- White-bellied redstart (Luscinia phoenicuroides)

- Bull-headed shrike (Lanius bucephalus)

- Red-backed shrike (Lanius collurio)

- Brown shrike (Lanius cristatus)

- Great grey shrike (Lanius excubitor)

- Lesser grey shrike (Lanius minor)

- Long-tailed shrike (Lanius schach)

- Woodchat shrike (Lanius senator)

- Tiger shrike (Lanius tigrinus)

- Silver-eared mesia (Leiothrix argentauris)

- Red-billed leiothrix (Leiothrix lutea)

- White-browed tit-warbler (Leptopoecile sophiae)

- Red-faced liocichla (Liocichla phoenicea)

- River warbler (Locustella fluviatilis)

- Savi's warbler (Locustella luscinioides)

- Brown bush warbler (Locustella luteoventris)

- Common grasshopper warbler (Locustella naevia)

- Middendorff's grasshopper warbler (Locustella ochotensis)

- Woodlark (Lullula arborea)

- Indian blue robin (Luscinia brunnea)

- Siberian rubythroat (Calliope calliope)

- Siberian blue robin (Luscinia cyane)

- Thrush nightingale (Luscinia luscinia)

- Common nightingale (Luscinia megarhynchos)

- Himalayan rubythroat (Luscinia pectoralis)

- Bluethroat (Luscinia svecica)

- Pin-striped tit-babbler (Macronous gularis)

- Striated grassbird (Megalurus palustris)

- Blue-winged minla (Minla cyanouroptera)

- Blue-capped rock thrush (Monticola cinclorhyncha)

- Monticola erythrogastra[26]

- White-throated rock thrush (Monticola gularis)

- Chestnut-bellied rock thrush (Monticola rufiventris)

- Common rock thrush (Monticola saxatilis)

- Blue rock thrush (Monticola solitarius)

- White wagtail (Motacilla alba)

- Grey wagtail (Motacilla cinerea)

- Citrine wagtail (Motacilla citreola)

- Western yellow wagtail (Motacilla flava)

- Japanese wagtail (Motacilla grandis)

- White wagtail (Motacilla alba)

- Motacilla sordidus[27]

- Brown-breasted flycatcher (Muscicapa muttui)

- Spotted flycatcher (Muscicapa striata)

- Verditer flycatcher (Eumyias thalassinus)

- White-winged grosbeak (Mycerobas carnipes)

- Blue whistling thrush (Myophonus caeruleus)

- Streaked wren-babbler (Napothera brevicaudata)

- Eyebrowed wren-babbler (Napothera epilepidota)

- Large niltava (Niltava grandis)

- Small niltava (Niltava macgrigoriae)

- Rufous-bellied niltava (Niltava sundara)

- Black-eared wheatear (Oenanthe hispanica)

- Isabelline wheatear (Oenanthe isabellina)

- Northern wheatear (Oenanthe oenanthe)

- Pied wheatear (Oenanthe pleschanka)

- Eurasian golden oriole (Oriolus oriolus)

- Dark-necked tailorbird (Orthotomus atrogularis)

- Common tailorbird (Orthotomus sutorius)

- Bearded reedling (Panurus biarmicus)

- Black-breasted parrotbill (Paradoxornis flavirostris)

- Vinous-throated parrotbill (Sinosuthora webbiana)

- Eurasian blue tit (Cyanistes caeruleus)

- Great tit (Parus major)

- Yellow-cheeked tit (Parus spilonotus)

- House sparrow (Passer domesticus)

- Spanish sparrow (Passer hispaniolensis)

- Eurasian tree sparrow (Passer montanus)

- Russet sparrow (Passer rutilans)

- Spot-throated babbler (Pellorneum albiventre)

- Buff-breasted babbler (Pellorneum tickelli)

- Puff-throated babbler (Pellorneum ruficeps)

- Grey-chinned minivet (Pericrocotus solaris)

- Daurian redstart (Phoenicurus auroreus)

- Eversmann's redstart (Phoenicurus erythronotus)

- Blue-fronted redstart (Phoenicurus frontalis)

- Plumbeous water redstart (Phoenicurus fuliginosus)

- Moussier's redstart (Phoenicurus moussieri)

- Black redstart (Phoenicurus ochruros)

- Common redstart (Phoenicurus phoenicurus)

- Thick-billed warbler (Phragmaticola aedon)

- Western Bonelli's warbler (Phylloscopus bonelli)

- Arctic warbler (Phylloscopus borealis)

- Yellow-vented warbler (Phylloscopus cantator)

- Common chiffchaff (Phylloscopus collybita)

- Sulphur-bellied warbler (Phylloscopus griseolus)

- Yellow-browed warbler (Phylloscopus inornatus)

- Pallas's leaf warbler (Phylloscopus proregulus)

- Blyth's leaf warbler (Phylloscopus reguloides)

- Wood warbler (Phylloscopus sibilatrix)

- Radde's warbler (Phylloscopus schwarzi)

- Willow warbler (Phylloscopus trochilus)

- Eurasian magpie (Pica pica)

- Scaly-breasted cupwing (Pnoepyga albiventer)

- Pygmy cupwing (Pnoepyga pusilla)

- Rusty-cheeked scimitar babbler (Pomatorhinus erythrogenys)

- Coral-billed scimitar babbler (Pomatorhinus ferruginosus)

- Streak-breasted scimitar babbler (Pomatorhinus ruficollis)

- White-browed scimitar babbler (Pomatorhinus schisticeps)

- Black-throated prinia (Prinia atrogularis)

- Striated prinia (Prinia criniger)

- Yellow-bellied prinia (Prinia flaviventris)

- Graceful prinia (Prinia gracilis)

- Rufescent prinia (Prinia rufescens)

- Tawny-flanked prinia (Prinia subflava)

- Black-throated accentor (Prunella atrogularis)

- Alpine accentor (Prunella collaris)

- Brown accentor (Prunella fulvescens)

- Dunnock (Prunella modularis)

- Robin accentor (Prunella rubeculoides)

- Rufous-breasted accentor (Prunella strophiata)

- Trilling shrike-babbler (Pteruthius aenobarbus)

- Red-vented bulbul (Pycnonotus cafer)

- Flavescent bulbul (Pycnonotus flavescens)

- Himalayan bulbul (Pycnonotus leucogenys)

- Black-capped bulbul (Pycnonotus melanicterus)

- Eurasian bullfinch (Pyrrhula pyrrhula)

- Goldcrest (Regulus regulus)

- White-throated fantail (Rhipidura albicollis)

- White-browed fantail (Rhipidura aureola)

- Desert finch (Rhodospiza obsoleta)

- Long-billed wren-babbler (Rimator malacoptilus)

- Pied bush chat (Saxicola caprata)

- Grey bush chat (Saxicola ferrea)

- White-tailed stonechat (Saxicola leucurus)

- Whinchat (Saxicola rubetra)

- Siberian stonechat (Saxicola maurus)[28]

- Streaked scrub warbler (Scotocerca inquieta)

- Green-crowned warbler (Seicercus burkii)

- Chestnut-crowned warbler (Seicercus castaniceps)[29]

- Grey-hooded warbler (Phylloscopus xanthoschistos)

- Atlantic canary (Serinus canaria)

- Red-fronted serin (Serinus pusillus)

- Indian nuthatch (Sitta castanea)

- Velvet-fronted nuthatch (Sitta frontalis)

- Tawny-breasted wren-babbler (Spelaeornis longicaudatus)

- Eurasian siskin (Spinus spinus)

- Crested finchbill (Spizixos canifrons)

- Grey-throated babbler (Stachyris nigriceps)

- Rufous-fronted babbler (Stachyris rufifrons)

- Common starling (Sturnus vulgaris)

- Eurasian blackcap (Sylvia atricapilla)

- Garden warbler (Sylvia borin)

- Subalpine warbler (Sylvia cantillans)

- Common whitethroat (Sylvia communis)

- Spectacled warbler (Sylvia conspicillata)

- Lesser whitethroat (Sylvia curruca)

- Tristram's warbler (Sylvia deserticola)

- Western Orphean warbler (Sylvia hortensis)

- Sardinian warbler (Sylvia melanocephala)

- Barred warbler (Sylvia nisoria)

- Dartford warbler (Sylvia undata)

- Indian paradise flycatcher (Terpsiphone paradisi)

- Grey-bellied tesia (Tesia cyaniventer)

- Chestnut-capped babbler (Timalia pileata)

- Brown-capped laughingthrush (Trochalopteron austeni)

- Striped laughingthrush (Trochalopteron virgatum)

- Eurasian wren (Troglodytes troglodytes)

- Japanese thrush (Turdus cardis)

- Black-breasted thrush (Turdus dissimilis)

- Redwing (Turdus iliacus)

- Common blackbird (Turdus merula)

- Eyebrowed thrush (Turdus obscurus)

- Song thrush (Turdus philomelos)

- Fieldfare (Turdus pilaris)

- Ring ouzel (Turdus torquatus)

- Tickell's thrush (Turdus unicolor)

- Mistle thrush (Turdus viscivorus)

- Long-tailed rosefinch (Uragus sibiricus)

- Pale-footed bush warbler (Urosphena pallidipes)

- Whiskered yuhina (Yuhina flavicollis)

- Rufous-vented yuhina (Yuhina occipitalis)

- Orange-headed thrush (Geokichla citrina)

- Dark-sided thrush (Zoothera marginata)

- Long-billed thrush (Zoothera monticola)

- Indian white-eye (Zosterops palpebrosa)

frame-style = border: 1px solid Plum;

Chicks

The naked, altricial chick hatches after 11–13 days.[2] It methodically evicts all host progeny from host nests. It is a much larger bird than its hosts, and needs to monopolize the food supplied by the parents. The chick will roll the other eggs out of the nest by pushing them with its back over the edge. If the host's eggs hatch before the cuckoo's, the cuckoo chick will push the other chicks out of the nest in a similar way. At 14 days old, the common cuckoo chick is about three times the size of an adult Eurasian reed warbler.

The necessity of eviction behavior is unclear. One hypothesis is that competing with host chicks leads to decreased cuckoo chick weight, which is selective pressure for eviction behavior. An analysis of the amount of food provided to common cuckoo chicks by host parents in the presence and absence of host siblings showed that when competing against host siblings, cuckoo chicks did not receive enough food, showing an inability to compete.[30] Selection pressure for eviction behavior may come from cuckoo chicks lacking the correct visual begging signals, hosts distributing food to all nestlings equally, or host recognition of the parasite.[30][31] Another hypothesis is that decreased cuckoo chick weight is not selective pressure for eviction behavior. An analysis of resources provided to cuckoo chick in the presence and absence of host siblings also showed that the weights of cuckoos raised with host chicks were much smaller upon fledging than cuckoos raised alone, but within 12 days cuckoos raised with siblings grew faster than cuckoos raised alone and made up for developmental differences, showing a flexibility that would not necessarily select for eviction behavior.[32]

Species whose broods are parasitised by the common cuckoo have evolved to discriminate against cuckoo eggs but not chicks.[33] Experiments have shown that common cuckoo chicks persuade their host parents to feed them by making a rapid begging call that sounds "remarkably like a whole brood of host chicks." The researchers suggested that "the cuckoo needs vocal trickery to stimulate adequate care to compensate for the fact that it presents a visual stimulus of just one gape."[31] However, a cuckoo chick needs the amount of food of a whole brood of host nestlings, and it struggles to elicit that much from the host parents with only the vocal stimulus. This may reflect a tradeoff—the cuckoo chick benefits from eviction by receiving all the food provided, but faces a cost in being the only one influencing feeding rate. For this reason, cuckoo chicks exploit host parental care by remaining with the host parent longer than host chicks do, both before and after fledging.[31]

Common cuckoo chicks fledge about 17–21 days after hatching,[2] compared to 12–13 days for Eurasian reed warblers.[34] If the hen cuckoo is out-of-phase with a clutch of Eurasian reed warbler eggs, she will eat them all so that the hosts are forced to start another brood.

The common cuckoo's behaviour was firstly observed and described by Aristotle and the combination of behaviour and anatomical adaptation by Edward Jenner, who was elected as Fellow of the Royal Society in 1788 for this work rather than for his development of the smallpox vaccine. It was first documented on film in 1922 by Edgar Chance and Oliver G Pike, in their film 'The Cuckoo's Secret'.[35]

A study in Japan found that young common cuckoos probably acquire species-specific feather lice from body-to-body contact with other cuckoos between the time of leaving the nest and returning to the breeding area in spring. A total of 21 nestlings were examined shortly before they left their hosts' nests and none carried feather lice. However, young birds returning to Japan for the first time were found just as likely as older individuals to be lousy.[36]

As a biodiversity indicator

The occurrence of common cuckoo in Europe is a good surrogate for biodiversity facets including taxonomic diversity and functional diversity in bird communities, and better than the traditional use of top predators as bioindicators. The reason for this is the strong correlation between the cuckoo's host species richness and overall bird species richness, due to co-evolutionary relationships.[37] This may be useful for citizen science.[38]

In culture

Aristotle was aware of the old tale that cuckoos turned into hawks in winter. The tale was an explanation for their absence outside the summer season, later accepted by Pliny the Elder in his Natural History. Aristotle rejected the claim, observing in his History of Animals that cuckoos do not have the predators' talons or hooked bills. These Classical era accounts were known to the Early Modern English naturalist, William Turner.[10]

The 13th century medieval English round, "Sumer Is Icumen In", celebrates the cuckoo as a sign of spring, the beginning of summer, in the first stanza, and in the chorus:[39]

Svmer is icumen in

|

Summer has arrived,

|

In England, William Shakespeare alludes to the common cuckoo's association with spring, and with cuckoldry,[40] in the courtly springtime song in his play Love's Labours Lost:[41][42]

- When daisies pied and violets blue

- And lady-smocks all silver-white

- And cuckoo-buds of yellow hue

- Do paint the meadows with delight,

- The cuckoo then, on every tree,

- Mocks married men; for thus sings he:

- "Cuckoo;

- Cuckoo, cuckoo!" O, word of fear,

- Unpleasing to a married ear!

In Europe, hearing the call of the common cuckoo is regarded as the first harbinger of spring. Many local legends and traditions are based on this. In Scotland, Gowk Stones (cuckoo stones) sometimes associated with the arrival of the first cuckoo of spring. "Gowk" is an old name for the common cuckoo in northern England,[43] derived from the harsh repeated "gowk" call the bird makes when excited.[4] The well-known cuckoo clock features a mechanical bird and is fitted with bellows and pipes that imitate the call of the common cuckoo.[44] Cuckoos feature in traditional rhymes, such as '"In April the cuckoo comes, In May she'll stay, In June she changes her tune, In July she prepares to fly, Come August, go she must,"' quoted Peggy. 'But you haven't said it all,' put in Bobby. '"And if the cuckoo stays till September, It's as much as the oldest man can remember."'[45]

On Hearing the First Cuckoo in Spring is a Symphonic poem from Norway composed for orchestra by Frederick Delius.[46]

Two English folk songs feature cuckoos. One usually called The Cuckoo starts:

The cuckoo is a fine bird and she sings as she flies,

She brings us good tidings, she tells us no lies.

She sucks little birds' eggs to make her voice clear,

And never sings cuckoo till the summer draws near[47]

The second, "The Cuckoo's Nest" is a song about a courtship, with the eponymous (and of course, non-existent) nest serving as a metaphor for the vulva and its tangled "nest" of pubic hair.

Some like a girl who is pretty in the face

and some like a girl who is slender in the waist

But give me a girl who will wriggle and will twist

At the bottom of the belly lies the cuckoo's nest......Me darling, says she, I can do no such thing

For me mother often told me it was committing sin

Me maidenhead to lose and me sex to be abused

So have no more to do with me cuckoo's nest[48]

One of the tales of the Wise Men of Gotham tells how they built a hedge round a tree in order to trap a cuckoo so that it would always be summer.[49]

References

- BirdLife International (2012). "Cuculus canorus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2012. Retrieved 26 November 2013.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Robinson, R. A. (2005). "Cuckoo Cuculus canorus". BirdFacts: Profiles of Birds Occurring in Britain & Ireland. British Trust for Ornithology. BTO Research Report 407. Retrieved 12 August 2011.

- Jobling, James A (2010). The Helm Dictionary of Scientific Bird Names. London: Christopher Helm. pp. 89, 124. ISBN 978-1-4081-2501-4.

- Snow, D. W.; Perrins, C. (1997). The Birds of the Western Palearctic (Abridged ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-854099-1.

- "Cuckoo". Oxford English Dictionary (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press. September 2005. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- "Common Cuckoo (Cuculus canorus)". Internet Bird Collection. Lynx Edicions. Retrieved 20 August 2011.

- Mullarney, K.; Svensson, L.; Zetterstrom, D.; Grant, P. (1999). Collins Bird Guide. HarperCollins. pp. 204–205. ISBN 978-0-00-219728-1.

- Baker, K. (1993). Identification Guide to European Non-Passerines. British Trust for Ornithology. pp. 273–275. ISBN 978-0-903793-18-6. BTO Guide 24.

- Welbergen, J.; Davies, N. B. (2011). "A parasite in wolf's clothing: hawk mimicry reduces mobbing of cuckoos by hosts". Behavioral Ecology. 22 (3): 574–579. doi:10.1093/beheco/arr008.

- Davies, N. B.; Welbergen, J. A. (2008). "Cuckoo–hawk mimicry? An experimental test". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 275 (1644): 1811–1816. doi:10.1098/rspb.2008.0331. PMC 2587796. PMID 18467298.

- Thorogood, R.; Davies, N. B. (2012). "Cuckoos combat socially transmitted defenses of reed warbler hosts with a plumage polymorphism". Science. 337 (6094): 578–580. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.1030.5702. doi:10.1126/science.1220759. PMID 22859487.

- Ali, Salim; Ripley, S. Dillon (1981). Handbook of the birds of India and Pakistan together with those of Bangladesh, Nepal, Bhutan and Ceylon. Volume 3. Stone Curlews to Owls (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 209.

- Denerley, Chloe; Redpath, Steve M.; Wal, Rene van der; Newson, Stuart E.; Chapman, Jason W.; Wilson, Jeremy D. (2019). "Breeding ground correlates of the distribution and decline of the Common Cuckoo Cuculus canorus at two spatial scales" (PDF). Ibis. 161 (2): 346–358. doi:10.1111/ibi.12612. hdl:10871/37563. ISSN 1474-919X.

- Barbaro, Luc; Battisti, Andrea (2011). "Birds as predators of the pine processionary moth (Lepidoptera: Notodontidae)". Biological Control. 56 (2): 107–114. doi:10.1016/j.biocontrol.2010.10.009.

- Moksnes, Arne; Røskaft, Eivin; Hagen, Lise Greger; Honza, Marcel; Mørk, Cecilie; Olsen, Per H. (2000). "Common Cuckoo Cuculus canorus and host behaviour at Reed Warbler Acrocephalus scirpaceus nests". Ibis. 142 (2): 247–258. doi:10.1111/j.1474-919X.2000.tb04864.x.

- Gibbs, H. L.; Sorenson, M. D.; Marchetti, K.; Brooke, M. D.; Davies, N. B.; Nakamura, H. (2000). "Genetic evidence for female host-specific races of the common cuckoo". Nature. 407 (6801): 183–186. doi:10.1038/35025058. PMID 11001055.

- Fossoy, F.; Antonov, A.; Moksnes, A.; Roskfaft, E.; Vikan, J. R.; Moller, A. P.; Shykoff, J. A.; Stokke, B. G. (2011). "Genetic differentiation among sympatric cuckoohost races: Males matter". Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 278 (1712): 1639–1645. doi:10.1098/rspb.2010.2090. PMC 3081775. PMID 21068043.

- Brennand, E. (24 March 2011). "Cuckoo in egg pattern 'arms race'". BBC News. Retrieved 22 August 2011.

- Moskát, C.; Honza, M. (2002). "European Cuckoo Cuculus canorus parasitism and host's rejection behaviour in a heavily parasitized Great Reed Warbler Acrocephalus arundinaceus population". Ibis. 144 (4): 614–622. doi:10.1046/j.1474-919X.2002.00085.x.

- Moskát, C.; Honza, M. (2000). "Effect of nest and nest site characteristics on the risk of cuckoo Cuculus canorus parasitism in the great reed warbler Acrocephalus arundinaceus". Ecography. 23 (3): 335–341. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0587.2000.tb00289.x.

- Marton, Attila; Fülöp, Attila; Ozogány, Katalin; Moskát, Csaba; Bán, Miklós (December 2019). "Host alarm calls attract the unwanted attention of the brood parasitic common cuckoo". Scientific Reports. 9 (1): 18563. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-54909-1. ISSN 2045-2322.

- Moskvitch, K. (24 September 2010). "Extra incubation time lets cuckoo chicks pop out early". BBC News. Retrieved 22 August 2011.

- Numerov, A. D. Inter-species and Intra-species brood parasitism in Birds. Voronezh: Voronezh University. 2003. 516 p. [In Russian] Нумеров А. Д. Межвидовой и внутривидовой гнездовой паразитизм у птиц. Воронеж: ФГУП ИПФ Воронеж. 2003. C. 38-40.

- as group of subspecies Carduelis carduelis caniceps of European goldfinch here

- The species is included in Emberiza bruniceps "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2015-07-02. Retrieved 2015-07-03.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) now

- Turdus erythrogaster Vigors, Proc. Zool. Soc. London, 1831, p. 171.; Monticola erythrogastra Baker, Faun. Brit. Ind., 2, p. 170. This form is recognized as younger synonym of Monticola rufiventris (Jardine and Selby)

- This scientific name does not correspond to any known species.

- There is the name Saxicola torquata sensu lato in the list, but now this species was split for three. In Western Siberia 25% of cuckoo's eggs (n=126) was found in the nests of Saxicola maura. The names changed according to this information. (Numerov, A. D. Order Cuculiformes. // Birds of Russia and adjacent countries. Moscow: Nauka. 1993. P. 212 [In Russian]).

- In Numerov's original list, this species appeared twice.

- Martín-Gálvez, D.; Soler, M.; Soler, J. J.; Martín-Vivaldi, M.; Palomino, J. J. (2005). "Food acquisition by common cuckoo chicks in rufous bush robin nests and the advantage of eviction behaviour". Animal Behaviour. 70 (6): 1313–1321. doi:10.1016/j.anbehav.2005.03.031.

- Davies, N. B.; Kilner, R. M.; Noble, D. G. (1998). "Nestling cuckoos, Cuculus canorus, exploit hosts with begging calls that mimic a brood". Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 265 (1397): 673–678. doi:10.1098/rspb.1998.0346. PMC 1689031.

- Geltsch, N.; Hauber, M. E.; Anderson, M. G.; Ban, M.; Moskát, C. (2012). "Competition with a host nestling for parental provisioning imposes recoverable costs on parasitic cuckoo chick's growth". Behavioural Processes. 90 (3): 378–383. doi:10.1016/j.beproc.2012.04.002. PMID 22521709.

- Davies, N. B.; de L. Brooke, M. (1989). "An experimental study of co-evolution between the Cuckoo, Cuculus canorus, and its hosts. II. Host egg markings, chick discrimination and general discussion". Journal of Animal Ecology. 58 (1): 225–236. doi:10.2307/4996. JSTOR 4996.

- Robinson, R. A. (2005). "Reed Warbler Acrocephalus scirpaceus". BirdFacts: Profiles of Birds Occurring in Britain & Ireland. British Trust for Ornithology. BTO Research Report 407. Retrieved 12 August 2011.

- "Oliver Pike". WildFilmHistory. Retrieved 25 September 2010.

- de L. Brooke, M.; Nakamura, H. (1998). "The acquisition of host-specific feather lice by common cuckoos (Cuculus canorus)". Journal of Zoology. 244 (2): 167–173. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.1998.tb00022.x.

- Tryjanowski, P.; Morelli, F. (2015). "Presence of Cuckoo reliably indicates high bird diversity: A case study in a farmland area". Ecological Indicators. 55: 52–58. doi:10.1016/j.ecolind.2015.03.012.

- Morelli, F.; Jiguet, F.; Reif, J.; Plexida, S.; Suzzi Valli, A.; Indykiewicz, P.; Šímová, S.; Tichit, M.; Moretti, M.; Tryjanowski, P. (2015). "Cuckoo and biodiversity: testing the correlation between species occurrence and bird species richness in Europe". Biological Conservation. 190: 123–132. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2015.06.003.

- Wulstan, David (2000). "'Sumer Is Icumen In': A Perpetual Puzzle-Canon?". Plainsong and Medieval Music. 9 (1 (April)): 1–17. doi:10.1017/S0961137100000012.

- "Cuckold". Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 31 May 2015.

- Shakespeare, William. "Song: "When daisies pied and violets blue"". Poetry Foundation. Retrieved 22 July 2015.

- Rhodes, Neil; Gillespie, Stuart (13 May 2014). Shakespeare And Elizabethan Popular Culture: Arden Critical Companion. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 178. ISBN 978-1-4081-4362-9.

- Lockwood, W. B. (1993). The Oxford Dictionary of British Bird Names. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-866196-2.

- "Beginners Guide". Cuckoo Clock World. Retrieved 21 April 2016.

- Brazil, Angela (1915). A Terrible Tomboy. Project Gutenberg EBook #38619.

- "On Hearing the First Cuckoo in Spring". IMSLP Petrucci Library. Retrieved 4 October 2019.

- Palmer, Roy (ed); English Country Songbook; London; 1979

- Traditional Songs website, http://www.traditionalmusic.co.uk/song-midis/Cuckoos_Nest.htm Retrieved 2017/03/07

- BBC Legacy web-page http://www.bbc.co.uk/legacies/myths_legends/england/nottingham/article_1.shtml Retrieved 2017/03/08

Further reading

- Wyllie, Ian (1981). The Cuckoo. London: B.T. Batsford.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Cuculus canorus. |

| Wikispecies has information related to Cuculus canorus |

- The Rules of Life. BBC/Open University. 2005.

- Ageing and sexing (PDF; 2.4 MB) by Javier Blasco-Zumeta & Gerd-Michael Heinze

- ARKive Still photos and videos.

- Common Cuckoo (Cuculus canorus) videos and photos at the Internet Bird Collection

- (European Cuckoo = ) Common Cuckoo - Species text in The Atlas of Southern African Birds.

- "Tracking Cuckoos to Africa... and back again". British Trust for Ornithology.