Cladistics

Cladistics (/kləˈdɪstɪks/, from Greek κλάδος, kládos, "branch")[1] is an approach to biological classification in which organisms are categorized in groups ("clades") based on the most recent common ancestor. Hypothesized relationships are typically based on shared derived characteristics (synapomorphies) that can be traced to the most recent common ancestor and are not present in more distant groups and ancestors. A key feature of a clade is that a common ancestor and all its descendants are part of the clade. Importantly, all descendants stay in their overarching ancestral clade. For example, if within a strict cladistic framework the terms animals, bilateria/worms, fishes/vertebrata, or monkeys/anthropoidea were used, these terms would include humans. Many of these terms are normally used paraphyletically, outside of cladistics, e.g. as a 'grade'. Radiation results in the generation of new subclades by bifurcation, but in practice sexual hybridization may blur very closely related groupings.[2][3][4][5]

| Part of a series on |

| Evolutionary biology |

|---|

Darwin's finches by John Gould |

|

Processes and outcomes

|

|

Natural history

|

|

History of evolutionary theory

|

|

Fields and applications

|

|

Social implications

|

|

The techniques and nomenclature of cladistics have been applied to disciplines other than biology. (See phylogenetic nomenclature.)

Cladistics is now the most commonly used method to classify organisms.[6]

History

The original methods used in cladistic analysis and the school of taxonomy derived from the work of the German entomologist Willi Hennig, who referred to it as phylogenetic systematics (also the title of his 1966 book); the terms "cladistics" and "clade" were popularized by other researchers. Cladistics in the original sense refers to a particular set of methods used in phylogenetic analysis, although it is now sometimes used to refer to the whole field.[7]

What is now called the cladistic method appeared as early as 1901 with a work by Peter Chalmers Mitchell for birds[8][9] and subsequently by Robert John Tillyard (for insects) in 1921,[10] and W. Zimmermann (for plants) in 1943.[11] The term "clade" was introduced in 1958 by Julian Huxley after having been coined by Lucien Cuénot in 1940,[12] "cladogenesis" in 1958,[13] "cladistic" by Arthur Cain and Harrison in 1960,[14] "cladist" (for an adherent of Hennig's school) by Ernst Mayr in 1965,[15] and "cladistics" in 1966.[13] Hennig referred to his own approach as "phylogenetic systematics". From the time of his original formulation until the end of the 1970s, cladistics competed as an analytical and philosophical approach to systematics with phenetics and so-called evolutionary taxonomy. Phenetics was championed at this time by the numerical taxonomists Peter Sneath and Robert Sokal, and evolutionary taxonomy by Ernst Mayr.

Originally conceived, if only in essence, by Willi Hennig in a book published in 1950, cladistics did not flourish until its translation into English in 1966 (Lewin 1997). Today, cladistics is the most popular method for constructing phylogenies from morphological data.

In the 1990s, the development of effective polymerase chain reaction techniques allowed the application of cladistic methods to biochemical and molecular genetic traits of organisms, vastly expanding the amount of data available for phylogenetics. At the same time, cladistics rapidly became popular in evolutionary biology, because computers made it possible to process large quantities of data about organisms and their characteristics.

Methodology

The cladistic method interprets each character state transformation implied by the distribution of shared character states among taxa (or other terminals) as a potential piece of evidence for grouping. The outcome of a cladistic analysis is a cladogram – a tree-shaped diagram (dendrogram)[16] that is interpreted to represent the best hypothesis of phylogenetic relationships. Although traditionally such cladograms were generated largely on the basis of morphological characters and originally calculated by hand, genetic sequencing data and computational phylogenetics are now commonly used in phylogenetic analyses, and the parsimony criterion has been abandoned by many phylogeneticists in favor of more "sophisticated" but less parsimonious evolutionary models of character state transformation. Cladists contend that these models are unjustified.

Every cladogram is based on a particular dataset analyzed with a particular method. Datasets are tables consisting of molecular, morphological, ethological[17] and/or other characters and a list of operational taxonomic units (OTUs), which may be genes, individuals, populations, species, or larger taxa that are presumed to be monophyletic and therefore to form, all together, one large clade; phylogenetic analysis infers the branching pattern within that clade. Different datasets and different methods, not to mention violations of the mentioned assumptions, often result in different cladograms. Only scientific investigation can show which is more likely to be correct.

Until recently, for example, cladograms like the following have generally been accepted as accurate representations of the ancestral relations among turtles, lizards, crocodilians, and birds:[18]

▼ |

| ||||||||||||||||||

If this phylogenetic hypothesis is correct, then the last common ancestor of turtles and birds, at the branch near the ▼ lived earlier than the last common ancestor of lizards and birds, near the ♦. Most molecular evidence, however, produces cladograms more like this:[19]

| |||||||||||||||||||

If this is accurate, then the last common ancestor of turtles and birds lived later than the last common ancestor of lizards and birds. Since the cladograms provide competing accounts of real events, at most one of them is correct.

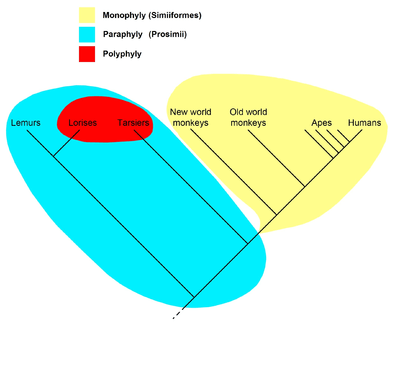

The cladogram to the right represents the current universally accepted hypothesis that all primates, including strepsirrhines like the lemurs and lorises, had a common ancestor all of whose descendants were primates, and so form a clade; the name Primates is therefore recognized for this clade. Within the primates, all anthropoids (monkeys, apes and humans) are hypothesized to have had a common ancestor all of whose descendants were anthropoids, so they form the clade called Anthropoidea. The "prosimians", on the other hand, form a paraphyletic taxon. The name Prosimii is not used in phylogenetic nomenclature, which names only clades; the "prosimians" are instead divided between the clades Strepsirhini and Haplorhini, where the latter contains Tarsiiformes and Anthropoidea.

Terminology for character states

The following terms, coined by Hennig, are used to identify shared or distinct character states among groups:[20][21][22]

- A plesiomorphy ("close form") or ancestral state is a character state that a taxon has retained from its ancestors. When two or more taxa that are not nested within each other share a plesiomorphy, it is a symplesiomorphy (from syn-, "together"). Symplesiomorphies do not mean that the taxa that exhibit that character state are necessarily closely related. For example, Reptilia is traditionally characterized by (among other things) being cold-blooded (i.e., not maintaining a constant high body temperature), whereas birds are warm-blooded. Since cold-bloodedness is a plesiomorphy, inherited from the common ancestor of traditional reptiles and birds, and thus a symplesiomorphy of turtles, snakes and crocodiles (among others), it does not mean that turtles, snakes and crocodiles form a clade that excludes the birds.

- An apomorphy ("separate form") or derived state is an innovation. It can thus be used to diagnose a clade – or even to help define a clade name in phylogenetic nomenclature. Features that are derived in individual taxa (a single species or a group that is represented by a single terminal in a given phylogenetic analysis) are called autapomorphies (from auto-, "self"). Autapomorphies express nothing about relationships among groups; clades are identified (or defined) by synapomorphies (from syn-, "together"). For example, the possession of digits that are homologous with those of Homo sapiens is a synapomorphy within the vertebrates. The tetrapods can be singled out as consisting of the first vertebrate with such digits homologous to those of Homo sapiens together with all descendants of this vertebrate (an apomorphy-based phylogenetic definition).[23] Importantly, snakes and other tetrapods that do not have digits are nonetheless tetrapods: other characters, such as amniotic eggs and diapsid skulls, indicate that they descended from ancestors that possessed digits which are homologous with ours.

- A character state is homoplastic or "an instance of homoplasy" if it is shared by two or more organisms but is absent from their common ancestor or from a later ancestor in the lineage leading to one of the organisms. It is therefore inferred to have evolved by convergence or reversal. Both mammals and birds are able to maintain a high constant body temperature (i.e., they are warm-blooded). However, the accepted cladogram explaining their significant features indicates that their common ancestor is in a group lacking this character state, so the state must have evolved independently in the two clades. Warm-bloodedness is separately a synapomorphy of mammals (or a larger clade) and of birds (or a larger clade), but it is not a synapomorphy of any group including both these clades. Hennig's Auxiliary Principle [24] states that shared character states should be considered evidence of grouping unless they are contradicted by the weight of other evidence; thus, homoplasy of some feature among members of a group may only be inferred after a phylogenetic hypothesis for that group has been established.

The terms plesiomorphy and apomorphy are relative; their application depends on the position of a group within a tree. For example, when trying to decide whether the tetrapods form a clade, an important question is whether having four limbs is a synapomorphy of the earliest taxa to be included within Tetrapoda: did all the earliest members of the Tetrapoda inherit four limbs from a common ancestor, whereas all other vertebrates did not, or at least not homologously? By contrast, for a group within the tetrapods, such as birds, having four limbs is a plesiomorphy. Using these two terms allows a greater precision in the discussion of homology, in particular allowing clear expression of the hierarchical relationships among different homologous features.

It can be difficult to decide whether a character state is in fact the same and thus can be classified as a synapomorphy, which may identify a monophyletic group, or whether it only appears to be the same and is thus a homoplasy, which cannot identify such a group. There is a danger of circular reasoning: assumptions about the shape of a phylogenetic tree are used to justify decisions about character states, which are then used as evidence for the shape of the tree.[25] Phylogenetics uses various forms of parsimony to decide such questions; the conclusions reached often depend on the dataset and the methods. Such is the nature of empirical science, and for this reason, most cladists refer to their cladograms as hypotheses of relationship. Cladograms that are supported by a large number and variety of different kinds of characters are viewed as more robust than those based on more limited evidence.

Terminology for taxa

Mono-, para- and polyphyletic taxa can be understood based on the shape of the tree (as done above), as well as based on their character states.[21][22][26] These are compared in the table below.

| Term | Node-based definition | Character-based definition |

|---|---|---|

| Monophyly | A clade, a monophyletic taxon, is a taxon that includes all descendants of an inferred ancestor. | A clade is characterized by one or more apomorphies: derived character states present in the first member of the taxon, inherited by its descendants (unless secondarily lost), and not inherited by any other taxa. |

| Paraphyly | A paraphyletic assemblage is one that is constructed by taking a clade and removing one or more smaller clades.[27] (Removing one clade produces a singly paraphyletic assemblage, removing two produces a doubly paraphylectic assemblage, and so on.)[28] | A paraphyletic assemblage is characterized by one or more plesiomorphies: character states inherited from ancestors but not present in all of their descendants. As a consequence, a paraphyletic assemblage is truncated, in that it excludes one or more clades from an otherwise monophyletic taxon. An alternative name is evolutionary grade, referring to an ancestral character state within the group. While paraphyletic assemblages are popular among paleontologists and evolutionary taxonomists, cladists do not recognize paraphyletic assemblages as having any formal information content – they are merely parts of clades. |

| Polyphyly | A polyphyletic assemblage is one which is neither monophyletic nor paraphyletic. | A polyphyletic assemblage is characterized by one or more homoplasies: character states which have converged or reverted so as to be the same but which have not been inherited from a common ancestor. No systematist recognizes polyphyletic assemblages as taxonomically meaningful entities, although ecologists sometimes consider them meaningful labels for functional participants in ecological communities (e. g., primary producers, detritivores, etc.). |

Criticism

Cladistics, either generally or in specific applications, has been criticized from its beginnings. Decisions as to whether particular character states are homologous, a precondition of their being synapomorphies, have been challenged as involving circular reasoning and subjective judgements.[29] Transformed cladistics arose in the late 1970s in an attempt to resolve some of these problems by removing phylogeny from cladistic analysis, but it has remained unpopular.

However, homology is usually determined from analysis of the results that are evaluated with homology measures, mainly the consistency index (CI) and retention index (RI), which, it has been claimed, makes the process objective. Also, homology can be equated to synapomorphy, which is what Patterson has done.[30]

Issues

In organisms with sexual reproduction, incomplete lineage sorting may result in inconsistent phylogenetic trees, depending on which genes are assessed.[31] It is also possible that multiple surviving lineages are generated while interbreeding is still significantly occurring (polytomy). Interbreeding is possible over periods of about 10 million years.[32][33] Typically speciation occurs over only about 1 million years,[34] which makes it less likely multiple long surviving lineages developed "simultaneously". Even so, interbreeding can result in a lineage being overwhelmed and absorbed by a related more numerous lineage. Simulation studies[35] suggest that phylogenetic trees are most accurately recovered from data that is morphologically coherent (i.e. where closely related organisms share the highest proportion of characters). This relationships is weaker in data generated under selection, potentially due to convergent evolution.

The cladistic method does not typically identify fossil species as actual ancestors of a clade.[36] Instead, they are identified as belonging to separate extinct branches. While a fossil species could be the actual ancestor of a clade, the default assumption is that they are more likely to be a related species.

In disciplines other than biology

The comparisons used to acquire data on which cladograms can be based are not limited to the field of biology.[37] Any group of individuals or classes that are hypothesized to have a common ancestor, and to which a set of common characteristics may or may not apply, can be compared pairwise. Cladograms can be used to depict the hypothetical descent relationships within groups of items in many different academic realms. The only requirement is that the items have characteristics that can be identified and measured.

Anthropology and archaeology:[38] Cladistic methods have been used to reconstruct the development of cultures or artifacts using groups of cultural traits or artifact features.

Comparative mythology and folktale use cladistic methods to reconstruct the protoversion of many myths. Mythological phylogenies constructed with mythemes clearly support low horizontal transmissions (borrowings), historical (sometimes Palaeolithic) diffusions and punctuated evolution.[39] They also are a powerful way to test hypotheses about cross-cultural relationships among folktales.[40][41]

Literature: Cladistic methods have been used in the classification of the surviving manuscripts of the Canterbury Tales,[42] and the manuscripts of the Sanskrit Charaka Samhita.[43]

Historical linguistics:[44] Cladistic methods have been used to reconstruct the phylogeny of languages using linguistic features. This is similar to the traditional comparative method of historical linguistics, but is more explicit in its use of parsimony and allows much faster analysis of large datasets (computational phylogenetics).

Textual criticism or stemmatics:[43][45] Cladistic methods have been used to reconstruct the phylogeny of manuscripts of the same work (and reconstruct the lost original) using distinctive copying errors as apomorphies. This differs from traditional historical-comparative linguistics in enabling the editor to evaluate and place in genetic relationship large groups of manuscripts with large numbers of variants that would be impossible to handle manually. It also enables parsimony analysis of contaminated traditions of transmission that would be impossible to evaluate manually in a reasonable period of time.

Astrophysics[46] infers the history of relationships between galaxies to create branching diagram hypotheses of galaxy diversification.

See also

- Bioinformatics

- Biomathematics

- Coalescent theory

- Common descent

- Glossary of scientific naming

- Language family

- Maximum parsimony

- Patrocladogram

- Phylogenetic network

- Scientific classification

- Stratocladistics

- Subclade

- Systematics

- Three-taxon analysis

- Tree model

- Tree structure

Notes and references

- Harper, Douglas. "clade". Online Etymology Dictionary.

- Columbia Encyclopedia

- "Introduction to Cladistics". Ucmp.berkeley.edu. Retrieved 6 January 2014.

- Oxford Dictionary of English

- Oxford English Dictionary

- "The Need for Cladistics". www.ucmp.berkeley.edu. Retrieved 12 August 2018.

- Brinkman & Leipe 2001, p. 323

- Schuh, Randall. 2000. Biological Systematics: Principles and Applications, p.7 (citing Nelson and Platnick, 1981). Cornell University Press (books.google)

- Folinsbee, Kaila et al. 2007. 5 Quantitative Approaches to Phylogenetics, p. 172. Rev. Mex. Div. 225-52 (kfolinsb.public.iastate.edu)

- Craw, RC (1992). "Margins of cladistics: Identity, differences and place in the emergence of phylogenetic systematics". In Griffiths, PE (ed.). Trees of life: Essays in the philosophy of biology. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic. pp. 65–107. ISBN 978-94-015-8038-0.

- Schuh, Randall. 2000. Biological Systematics: Principles and Applications, p.7. Cornell U. Press

- Cuénot 1940

- Webster's 9th New Collegiate Dictionary

- Cain & Harrison 1960

- Dupuis 1984

- Weygoldt 1998

- Jerison 2003, p. 254

- Benton, Michael J. (2005), Vertebrate Palaeontology, Blackwell, pp. 214, 233, ISBN 978-0-632-05637-8

- Lyson, Tyler; Gilbert, Scott F. (March–April 2009), "Turtles all the way down: loggerheads at the root of the chelonian tree" (PDF), Evolution & Development, 11 (2): 133–135, CiteSeerX 10.1.1.695.4249, doi:10.1111/j.1525-142X.2009.00325.x, PMID 19245543

- Patterson 1982, pp. 21–74

- Patterson 1988

- de Pinna 1991

- Laurin & Anderson 2004

- Hennig 1966

- James & Pourtless IV 2009, p. 25: "Synapomorphies are invoked to defend the hypothesis; the hypothesis is invoked to defend the synapomorphies."

- Patterson 1982

- Many sources give a verbal definition of 'paraphyletic' that does not require the missing groups to be monophyletic. However, when diagrams are presented representing paraphyletic groups, these invariably show the missing groups as monophyletic. See e.g.Wiley et al. 1991, p. 4

- Taylor 2003

- Adrain, Edgecombe & Lieberman 2002, pp. 56–57

- Forey, Peter et al. 1992. Cladistics,1st ed., p. 9, Oxford U. Press.

- Rogers, Jeffrey; Gibbs, Richard A. (1 May 2014). "Comparative primate genomics: emerging patterns of genome content and dynamics". Nature Reviews Genetics. 15 (5): 347–359. doi:10.1038/nrg3707. PMC 4113315. PMID 24709753.

- "Distant Species Produce Hybrid 60 Million Years After Their Split". IFLScience. Retrieved 24 March 2019.

- Mallet, James (1 May 2005). "Hybridization as an invasion of the genome". Trends in Ecology & Evolution. 20 (5): 229–237. doi:10.1016/j.tree.2005.02.010. ISSN 0169-5347. PMID 16701374.

- "How (and how fast) do new species form?". Why Evolution Is True. 4 January 2017. Retrieved 24 March 2019.

- Garwood, Russell J; Knight, Christopher G; Sutton, Mark D; Sansom, Robert S; Keating, Joseph N (2020). "Morphological Phylogenetics Evaluated Using Novel Evolutionary Simulations". Systematic Biology. doi:10.1093/sysbio/syaa012. ISSN 1063-5157.

- Krell, Frank-T; Cranston, Peter S. (2004). "Which side of the tree is more basal?: Editorial". Systematic Entomology. 29 (3): 279–281. doi:10.1111/j.0307-6970.2004.00262.x.

- Mace, Clare & Shennan 2005, p. 1

- Lipo et al. 2006

- d'Huy 2012a, b; d'Huy 2013a, b, c, d

- Ross and al. 2013

- Tehrani 2013

- "Canterbury Tales Project". Archived from the original on 7 July 2009. Retrieved 4 July 2009.

- Maas 2010–2011

- Oppenheimer 2006, pp. 290–300, 340–56

- Robinson & O’Hara 1996

- Fraix-Burnet et al. 2006

Bibliography

- Adrain, Jonathan M.; Edgecombe, Gregory D. & Lieberman, Bruce S. (2002), Fossils, Phylogeny, and Form: An Analytical Approach, New York: Kluwer Academic, ISBN 978-0-306-46721-9, retrieved 15 August 2012

- Baron, C. & Høeg, J.T. (2005), "Gould, Scharm and the paleontologocal perspective in evolutionary biology", in Koenemann, S. & Jenner, R.A. (eds.), Crustacea and Arthropod Relationships, CRC Press, pp. 3–14, ISBN 978-0-8493-3498-6, retrieved 15 October 2008

- Benton, M. J. (2000), "Stems, nodes, crown clades, and rank-free lists: is Linnaeus dead?" (PDF), Biological Reviews, 75 (4): 633–648, CiteSeerX 10.1.1.573.4518, doi:10.1111/j.1469-185X.2000.tb00055.x, PMID 11117201, archived from the original (PDF) on 9 August 2017, retrieved 2 October 2011

- Benton, M. J. (2004), Vertebrate Palaeontology (3rd ed.), Oxford: Blackwell Science, ISBN 978-0-632-05637-8

- Brinkman, Fiona S.L. & Leipe, Detlef D. (2001), "Phylogenetic analysis" (PDF), in Baxevanis, Andreas D. & Ouellette, B.F. Francis (eds.), Bioinformatics: a practical guide to the analysis of genes and proteins (2nd ed.), pp. 323–358, archived from the original (PDF) on 20 October 2013, retrieved 19 October 2013

- Cain, A. J.; Harrison, G. A. (1960), "Phyletic weighting", Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London, 35: 1–31

- Cuénot, Lucien (1940), "Remarques sur un essai d'arbre généalogique du règne animal", Comptes Rendus de l'Académie des Sciences de Paris, 210: 23–27.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) Available free online at Gallica (No direct URL). This is the paper credited by Hennig 1979 for the first use of the term 'clade'.

- Dupuis, Claude (1984), "Willi Hennig's impact on taxonomic thought", Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics, 15: 1–24, doi:10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.15.1.1, ISSN 0066-4162.

- Farris, James S. (1977), "On the phenetic approach to vertebrate classification", in Hecht, M. K.; Goody, P. C.; Hecht, B. M. (eds.), Major Patterns in Vertebrate Evolution, Plenum, New York, pp. 823–850

- Farris, James S. (1979a), "On the naturalness of phylogenetic classification", Systematic Zoology, 28 (2): 200–214, doi:10.2307/2412523, JSTOR 2412523

- Farris, James S. (1979b), "The information content of the phylogenetic system", Systematic Zoology, 28 (4): 483–519, doi:10.2307/2412562, JSTOR 2412562

- Farris, James S. (1980), "The efficient diagnoses of the phylogenetic system", Systematic Zoology, 29 (4): 386–401, doi:10.2307/2992344, JSTOR 2992344

- Farris, James S. (1983), "The logical basis of phylogenetic analysis", in Platnick, Norman I.; Funk, Vicki A. (eds.), Advances in Cladistics, vol. 2, Columbia University Press, New York, pp. 7–36

- Fraix-Burnet, D.; Choler, P.; Douzery, E.J.P.; Verhamme, A. (2006), "Astrocladistics: A Phylogenetic Analysis of Galaxy Evolution II. Formation and Diversification of Galaxies", Journal of Classification, 23 (1): 57–78, arXiv:astro-ph/0602580, Bibcode:2006JClas..23...57F, doi:10.1007/s00357-006-0004-4

- Hennig, Willi (1966), Phylogenetic systematics (tr. D. Dwight Davis and Rainer Zangerl), Urbana, IL: Univ. of Illinois Press (reprinted 1979 and 1999), ISBN 978-0-252-06814-0

- Hennig, Willi (1975), "'Cladistic analysis or cladistic classification?': a reply to Ernst Mayr" (PDF), Systematic Zoology, 24 (2): 244–256, doi:10.2307/2412765, JSTOR 2412765, responding to Mayr 1974.

- Hennig, Willi (1999), Phylogenetic systematics (3rd edition of 1966 book), Urbana: University of Illinois Press, ISBN 978-0-252-06814-0 Translated from manuscript in German eventually published in 1982 (Phylogenetische Systematik, Verlag Paul Parey, Berlin).

- Hull, David (1988), Science as a Process, University of Chicago Press, ISBN 978-0-226-36051-5

- James, Frances C. & Pourtless IV, John A. (2009), Cladistics and the Origin of Birds: A Review and Two New Analyses (PDF), Ornithological Monographs, No. 66, American Ornithologists' Union, ISBN 978-0-943610-85-6, retrieved 14 December 2010

- d'Huy, Julien (2012a). "Un ours dans les étoiles: recherche phylogénétique sur un mythe préhistorique". Préhistoire du Sud-Ouest. 20 (1): 91–106.

- d'Huy, Julien (2012b), "Le motif de Pygmalion : origine afrasienne et diffusion en Afrique". Sahara, 23: 49-59 .

- d'Huy, Julien (2013a), "Polyphemus (Aa. Th. 1137). "A phylogenetic reconstruction of a prehistoric tale". Nouvelle Mythologie Comparée / New Comparative Mythology 1,

- d'Huy, Julien (2013b). "A phylogenetic approach of mythology and its archaeological consequences". Rock Art Research. 30 (1): 115–118.

- d'Huy, Julien (2013c) "Les mythes évolueraient par ponctuations". Mythologie française, 252, 2013c: 8-12.

- d'Huy, Julien (2013d) "A Cosmic Hunt in the Berber sky : a phylogenetic reconstruction of Palaeolithic mythology". Les Cahiers de l'AARS, 15, 2013d: 93-106.

- Jerison, Harry J. (2003), "On Theory in Comparative Psychology", in Sternberg, Robert J.; Kaufman, James C. (eds.), The Evolution of Intelligence, Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc., ISBN 978-0-12-385250-2

- Laurin, M. & Anderson, J. (2004), "Meaning of the Name Tetrapoda in the Scientific Literature: An Exchange" (PDF), Systematic Biology, 53 (1): 68–80, doi:10.1080/10635150490264716, PMID 14965901

- Lipo, Carl; O'Brien, Michael J.; Collard, Mark; et al., eds. (2006), Mapping Our Ancestors: Phylogenetic Approaches in Anthropology and Prehistory, Piscataway: Transaction Publishers, ISBN 978-0-202-30751-0

- Maas, Philipp (2010–2011), Jürgen, Hanneder; Maas, Philipp (eds.), "Computer Aided Stemmatics — The Case of Fifty-Two Text Versions of Carakasasaṃhitā Vimānasthāna 8.67-157", Wiener Zeitschrift für die Kunde Südasiens, 52–53: 63–120, doi:10.1553/wzks2009-2010s63

- Mace, Ruth; Clare, Clare J.; Shennan, Stephen, eds. (2005), The Evolution of Cultural Diversity: A Phylogenetic Approach, Portland: Cavendish Press, ISBN 978-1-84472-099-6

- Mayr, Ernst (1974), "Cladistic analysis or cladistic classification?" (PDF), Zeitschrift für Zoologische Systematik und Evolutionsforschung, 12: 94–128, doi:10.1111/j.1439-0469.1974.tb00160.x, retrieved 14 December 2010

- Mayr, Ernst (1976), Evolution and the diversity of life (Selected essays), Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, ISBN 978-0-674-27105-0 Reissued 1997 in paperback. Includes a reprint of Mayr's 1974 anti-cladistics paper at pp. 433–476, "Cladistic analysis or cladistic classification." This is the paper to which Hennig 1975 is a response.

- Mayr, Ernst (1978), "Origin and history of some terms in systematic and evolutionary biology", Systematic Zoology, 27 (1): 83–88, doi:10.2307/2412818, JSTOR 2412818.

- Mayr, Ernst (1982), The growth of biological thought: diversity, evolution and inheritance, Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, ISBN 978-0-674-36446-2

- Oppenheimer, Stephen (2006), The Origins of the British, London: Robinson, ISBN 978-0-7867-1890-0

- Patterson, Colin (1982), "Morphological characters and homology", in Joysey, Kenneth A; Friday, A. E. (eds.), Problems in Phylogenetic Reconstruction, Systematics Association Special Volume 21, London: Academic Press, ISBN 978-0-12-391250-3.

- Patterson, Colin (1988), "Homology in classical and molecular biology", Molecular Biology and Evolution, 5 (6): 603–625, doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040523, PMID 3065587

- de Pinna, M.G.G (1991), "Concepts and tests of homology in the cladistic paradigm" (PDF), Cladistics, 7 (4): 367–394, CiteSeerX 10.1.1.487.2259, doi:10.1111/j.1096-0031.1991.tb00045.x

- de Queiroz, K. & Gauthier, J. (1992), "Phylogenetic taxonomy" (PDF), Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics, 23: 449–480, doi:10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.23.1.449

- Robinson, Peter M.W. & O’Hara, Robert J. (1996), "Cladistic analysis of an Old Norse manuscript tradition", Research in Humanities Computing, 4: 115–137, retrieved 13 December 2010

- Ross, Robert M.; Greenhill, Simon J.; Atkinson, Quentin D. (2013). "Population structure and cultural geography of a folktale in Europe". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 280 (1756): 20123065. doi:10.1098/rspb.2012.3065. PMC 3574383. PMID 23390109.

- Schuh, Randall T. & Brower, Andrew V.Z. (2009), Biological Systematics: Principles and Applications (2nd ed.), Cornell University Press, ISBN 978-0-8014-4799-0

- Taylor, Mike (2003), What do terms like monophyletic, paraphyletic and polyphyletic mean?, retrieved 13 December 2010

- Tehrani, Jamshid J., 2013, "The Phylogeny of Little Red Riding Hood", PLOS ONE, November 13.

- Tremblay, Frederic (2013), "Nicolai Hartmann and the Metaphysical Foundation of Phylogenetic Systematics", Biological Theory, 7 (1): 56–68, doi:10.1007/s13752-012-0077-8

- Weygoldt, P. (February 1998), "Evolution and systematics of the Chelicerata", Experimental and Applied Acarology, 22 (2): 63–79, doi:10.1023/A:1006037525704

- Wheeler, Quentin (2000), Species Concepts and Phylogenetic Theory: A Debate, Columbia University Press, ISBN 978-0-231-10143-1

- Wiley, E.O.; Siegel-Causey, D.; Brooks, D.R. & Funk, V.A. (1991), "Chapter 1 Introduction, terms and concepts", The Compleat Cladist: A Primer of Phylogenetic Procedures (PDF), The University of Kansas Museum of Natural History, ISBN 978-0-89338-035-9, retrieved 13 December 2010

- Williams, P.A. (1992), "Confusion in cladism", Synthese, 01 (1–2): 135–152, doi:10.1007/BF00484973

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Cladistics. |

- Willi Hennig Society

- Cladistics (scholarly journal of the Willi Hennig Society)

- Collins, Allen G.; Guralnick, Rob; Smith, Dave (1994–2005). "Journey into Phylogenetic Systematics". University of California Museum of Paleontology. Retrieved 21 January 2010.

- Felsenstein, Joe. "Phylogeny Programs". Seattle: University of Washington. Retrieved 21 January 2010.

- O'Neil, Dennis (1998–2008). "Classification of Living Things". San Marcos CA: Palomar College. Retrieved 21 January 2010.

- Robinson, Peter; O'Hara, Robert J. (1992). "Report on the Textual Criticism Challenge 1991". rjohara.net. Retrieved 21 January 2010.

- Theobald, Douglas (1999–2004). "Phylogenetics Primer". The TalkOrigins Archive. Retrieved 21 January 2010.