Cesar Chavez

Cesar Chavez (born César Estrada Chávez, locally [ˈsesaɾ esˈtɾaða ˈtʃaβes]; March 31, 1927 – April 23, 1993) was an American labor leader, community organizer, and Latino American civil rights activist. Along with Dolores Huerta, he co-founded the National Farm Workers Association (NFWA), which later merged to become the United Farm Workers (UFW) union. Ideologically, his world-view combined leftist politics with Roman Catholic social teachings.

Cesar Chavez | |

|---|---|

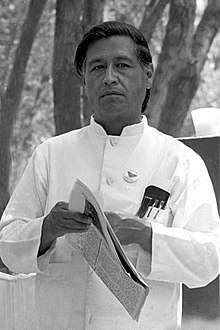

Chavez in 1974 | |

| Born | César Estrada Chávez March 31, 1927 Yuma, Arizona, U.S. |

| Died | April 23, 1993 (aged 66) San Luis, Arizona, U.S. |

| Occupation |

|

| Spouse(s) | Helen Fabela Chávez |

| Children | 8 |

| Awards | Presidential Medal of Freedom (1994) |

Born in Yuma, Arizona, to a Mexican American family, Chavez began his working life as a manual laborer before spending two years in the United States Navy. Relocating to California, where he married, he got involved in the Community Service Organization (CSO), through which he helped laborers register to vote. In 1959, he became the CSO's national director, a position based in Los Angeles. In 1962, he left the CSO to co-found the NFWA, based in Delano, California. Through this, he launched an insurance scheme, credit union, and newspaper for farmworkers. Later that decade he began organizing strikes among farmworkers, most notably the Delano grape strike of 1965–70. Influenced by the ideals of Indian independence leader Mahatma Gandhi, he emphasized the use of direct but nonviolent tactics to pressure farm owners into granting strikers' demands. He imbued his campaign with Catholic symbolism, including public processions, masses, and fasts. He called for a national boycott of California grapes, bringing him to nationwide attention. Critics within the union raised concerns about his strong personal control of the movement, the growing personality cult among supporters, and the purges of those deemed disloyal.

By the late 1970s, his tactics had forced growers to recognize the UFW as the bargaining agent for 50,000 field workers in California and Florida. Chavez's activities were strongly promoted by the American labor movement, which was eager to enroll Hispanic members, as well as leftist groups such as the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee. He also campaigned for the Democratic Party politician Robert F. Kennedy. In later life, he also became an advocate for veganism. Membership of the UFW dwindled in the 1980s and Chavez moved into real-estate development. Although the UFW faltered a few years after Chavez died in 1993, his work led to numerous improvements for union laborers.

Chavez was a controversial figure. During his life, many farm-owners considered him a communist subversive and the Federal Bureau of Investigation monitored him. He nevertheless became an icon for organized labor and leftist politics, as well as for the Hispanic American community; he posthumously became a "folk saint" among Mexican Americans.[1] His birthday, March 31, is a federal commemorative holiday (Cesar Chavez Day) in several U.S. states, while many schools, streets, and parks are named after him, and in 1994, he posthumously received the Presidential Medal of Freedom.

Early life

Childhood: 1927–1945

Cesar Estrada Chavez was born in Yuma, Arizona on March 31, 1927.[2] He was named for his paternal grandfather, Cesario Chavez, a Mexican who had crossed into Texas in 1898.[3] Cesario had established a successful wood haulage business near Yuma and in 1906 bought a farm in the Sonora Desert's North Gila Valley.[4] Cesario had brought his wife Dorotea and eight children with him from Mexico; the youngest, Librado, was Cesar's father.[3] Librado married Juana Estrada Chavez in the early 1920s.[5] Born in Ascensión, Chihuahua, she had crossed into the U.S. with her mother as a baby. They lived in Picacho, California before moving to Yuma, where Juana worked as a farm laborer and then an assistant to the chancellor of the University of Arizona.[6] Librado and Juana's first child, Rita, was born in August 1925, with their first son, Cesar, following nearly two years later.[7] In November 1925, Librado and Juana bought a series of buildings near to the family home which included a pool hall, store, and living quarters. They soon fell into debt and were forced to sell these assets, in April 1929 moving into the galera storeroom of Librado's parental home, then owned by the widowed Dorotea.[8]

Chavez was raised in what his biographer Miriam Pawel called "a typical extended Mexican family";[3] she noted that they were "not well-off, but they were comfortable, well clothed, and never hungry".[9] The family spoke in Spanish,[10] and he was raised as a Roman Catholic, with his paternal grandmother Dorotea largely overseeing his religious instruction;[11] his mother Juana engaged in forms of folk Catholicism, being a devotee of Santa Eduviges.[12] As a child, Chavez was nicknamed "Manzi" in reference to his fondness for manzanilla tea.[7] To entertain himself, he played handball and listened to boxing matches on the radio.[13] One of six children, he had two sisters, Rita and Vicki, and two brothers, Richard and Librado.[14][15]

He began attending Laguna Dam School in 1933; there, the speaking of Spanish was forbidden and Cesario was expected to change his name to Cesar.[16] After Dorotea died in July 1937, the Yuma County local government auctioned off her farmstead to cover back taxes, and despite Librado's delaying tactics, the house and land were sold in 1939.[17] This was a seminal experience for Cesar, who regarded it as an injustice against his family, with the banks, lawyers, and Anglo-American power structure as the villains of the incident.[18] Influenced by his Roman Catholic beliefs, he increasingly came to see the poor as a source of moral goodness in society.[19]

The Chavez family joined the growing number of American migrants who were moving to California amid the Great Depression.[20] First working as avocado pickers in Oxnard and then as pea pickers in Pescadero, the family made it to San Jose, where they first lived in a garage in the city's impoverished Mexican district.[21] They moved regularly, and at weekends and holidays, Cesar joined his family in working as an agricultural laborer.[22] In California, he moved schools many times, spending the longest time at Miguel Hidalgo Junior School; here, his grades were generally average, although he excelled at mathematics.[23] At school, he faced ridicule for his poverty,[21] while more broadly, he experienced anti-Latino prejudice from many European-Americans, with many establishments refusing to serve non-white customers.[24] He graduated from junior high in June 1942, after which he left formal education and became a full-time farm laborer.[23][25]

Early adulthood: 1946–1953

In March 1946, Chavez enlisted in the United States Navy, and was sent to the Naval Training Center San Diego.[26] In July he was stationed at the U.S. base in Saipan, and six months later moved to Guam, where he was promoted to the rank of seaman first class.[27] He was then stationed to San Francisco, where he decided to leave the Navy, receiving an honorable discharge in January 1948.[28] Relocating to Delano, California, where his family had settled, he returned to working as an agricultural laborer.[29]

Chavez entered a relationship with Helen Fabela, who soon became pregnant.[30] They married in Reno, Nevada in October 1948; it was a double wedding, with Chavez's sister Rita marrying her fiancé at the same ceremony.[31] By early 1949, Chavez and his new wife had settled in the Sal Si Puedes neighborhood of San Jose, where many of his other family members were now living.[32] Their first child, Fernando, was born there in February 1949; a second, Sylvia, followed in February 1950; and then a third, Linda, in January 1951.[31] The latter had been born shortly after they had relocated to Crescent City, where Chavez was employed in the lumber industry.[31] They then returned to San Jose, where Chavez worked as an apricot picker and then as a lumber handler for the General Box Company.[33]

Here, he befriended two social justice activists, Fred Ross and Father Donald McDonnell, both European-Americans whose activism was primarily within the Mexican-American community.[34] Chavez helped Ross establish a chapter of his Community Service Organization (CSO) in San Jose, and joined him in voter registration drives.[35] He was soon voted vice president of the CSO chapter.[36] He also helped McDonnell construct the first purpose-built church in Sal Si Puedes, the Our Lady of Guadalupe church, which was opened in December 1953.[37] In turn, McDonnell lent Chavez books, encouraging the latter to develop a love of reading. Among the books were biographies of the saint Francis of Assisi, the U.S. labour organizers John L. Lewis and Eugene V. Debs, and the Indian independence activist Mahatma Gandhi, introducing Chavez to the ideas of non-violent protest.[38]

Early activism

Working for the Community Service Organization: 1953–1962

In late 1953, Chavez was laid off by the General Box Company.[39] Ross then secured funds so that the CSO could employ Chavez as an organizer, travelling around California setting up other chapters.[40] In this job, he travelled across Decoto, Salinas, Fresno, Brawley, San Bernardino, Madera, and Bakersfield.[41] Many of the CSO chapters fell apart after Ross or Chavez ceased running them, and to prevent this Saul Alinsky advised them to unite the chapters, of which there were over twenty, into a self-sustaining national organisation.[42] In late 1955, Chavez returned to San Jose to rebuild the CSO chapter there so that it could sustain an employed full-time organizer. To raise funds, he opened a rummage store, organized a three-day carnival and sold Christmas trees, although often made a loss.[43]

In early 1957 he moved to Brawley to rebuild the chapter there.[44] His repeated moving meant that his family were regularly uprooted;[45] he saw little of his wife and children, and was absent for the birth of his sixth child.[46] Chavez grew increasingly disillusioned with the CSO, believing that middle-class members were becoming increasingly dominant and were pushing its priorities and allocation of funds in directions he disapproved of; he for instance opposed the decision to hold the organization's 1957 convention in Fresco's Hacienda Hotel, arguing that its prices were prohibitive for poorer members.[47] Amid the wider context of the Cold War and McCarthyite suspicions that leftist activism was a front for Marxist-Leninist groups, the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) began monitoring Chavez and opened a file on him.[48]

At Alinsky's instigation, the United Packinghouse Workers of America (UPWA) paid $20,000 to the CSO for the latter to open a branch in Oxnard; Chavez became its organizer, working with the largely Mexican farm laborers.[49] In Oxnard, Chavez worked to encourage voter registration.[50] He repeatedly heard concerns from local Mexican-American laborers that they were being routinely passed over or fired so that employers could hire cheaper Mexican guest workers, or braceros, in violation of federal law.[51] To combat this practice, he established the CSO Employment Committee that launched a "registration campaign" through which unemployed farm-workers could sign their name to highlight their desire for work.[52]

— Cesar Chavez, on avoiding the pitfalls of the CSO[53]

The Committee targeted its criticism at Hector Zamora, the director of the Ventura County Farm Labourers Association, who controlled the most jobs in the area.[54] It also used sit ins of workers to raise the profile of their cause, a tactic also being used by proponents of the civil rights movement in the South at that time.[55] It had some success in getting companies to replace braceros with unemployed Americans.[56] Its campaign also ensured that federal officials began properly investigating complaints about the use of braceros and received assurances from the state farm placement service that they would seek out unemployed Americans rather than automatically hiring bracero labor.[57] In May, the Employment Committee was formerly transferred from the CSO to the UPWA.[58]

In 1959, Chavez moved to Los Angeles to become the CSO's national director.[59] He, his wife, and (now) eight children settled into the largely Mexican neighborhood of Boyle Heights.[60] He found the CSO's financial situation was bad, with even his own salary in jeopardy.[60] He laid off several organizers to keep the organization afloat.[61] He tried to organise a life insurance scheme among CSO members to raise funds, but this project failed to materialise.[62] Under Chavez, the CSO secured financing from wealthier donors and organisations, usually to finance specific projects for a set period of time. The California American Federation of Labor and Congress of Industrial Organizations (AFL-CIO) for instance paid it $12,000 to conduct voter registration schemes in six counties with high Mexican populations.[63] The wealthy benefactor Katy Peake then offered it $50,000 over three years to organise California's farm workers.[64] Under Chavez's leadership, the CSO assisted the successful campaign to get the government to extend the state pension to non-citizens who were permanent residents.[65] At the ninth annual CSO convention in March 1962, Chavez resigned.[66]

Founding the National Farm Workers Association: 1962–65

.jpg)

In April 1962, Chavez and his family moved to Delano, where they rented a house on Kensington Street.[67] He was intent on forming a labor union for farm workers but, to conceal this aim, told people that he was simply conducting a census of farm workers to determine their needs.[68] He began devising the National Farm Workers Association (NFWA), referring to it as a "movement" rather than a trade union.[69] He was aided in this project both by his wife and by Dolores Huerta;[70] according to Pawel, Huerta became his "indispensable, lifelong ally".[71] Other key supporters of his project were the Reverend Jim Drake and other members of the California Migrant Ministry; although as a Roman Catholic Chavez was initially suspicious of these Protestant preachers, he came to view them as key allies.[72]

Chavez spent his days traveling around the San Joaquin Valley, meeting with workers and encouraging them to join his association.[73] At the time, he lived off a combination of unemployment benefit, his wife's wage as a farmworker, and donations from friends and sympathizers.[74] On 30 September 1962 he formalized the Association at a convention in Fresno.[75] There, delegates elected Chavez as the group's general-director.[76] They also agreed that, once the association had a life insurance policy up and running, members would start paying monthly dues of $3.50.[77] The group adopted the motto "viva la causa" ("long live the cause") and a flag featuring a black eagle on a red and white background.[78] At the organization's constitutional convention held in Fresno in January 1963, Chavez was elected president, with Huerta, Julio Hernandez, and Gilbert Padilla its vice presidents.[79]

Chavez wanted to control the NFWA's direction and to that end ensured that the role of the group's officers was largely ceremonial, with control of the group being primarily in the hands of the staff, headed by himself.[80] At the NFWA's second convention, held in Delano in 1963, Chavez was retained as its general director while the role of the presidency was scrapped.[80] That year, he began collecting membership dues, before establishing an insurance policy for FWA members.[81] Later in the year he launched a credit union for NFWA members, having gained a state charter after the federal government refused him one.[82] The NFWA attracted volunteers from other parts of the country. One of these, Bill Esher, became editor of the group's newspaper, El Malcriado, which soon after launching increased its print run from 1000 to 3000 to meet demand.[83]

The NFWA was initially based out of Chavez's house although in September 1964 it moved its headquarters to an abandoned Pentecostal church in Albany Street, West Delano.[84] During its second full year in operation the association more than doubled both its income and its expenditures.[85] As it became more secure, it began to plan for its first strike.[85] In April 1965, rose grafters approached the organization and requested help in organizing their strike for better working conditions. The strike targeted two companies, Mount Arbor and Conklin. Aided by the NFWA, the workers struck on May 3, and after four days the growers agreed to raise wages, and which the strikers returned to work.[86] Following this success, Chavez's reputation began to filter through leftist activist circles across California.[87]

The Delano Grape Strike

Start of the Delano Grape Strike: 1965–1966

In September 1965, Filipino American farm workers, organized by the Agricultural Workers Organizing Committee (AWOC), initiated the Delano grape strike to protest for higher wages. Chavez and his largely Mexican American supporters voted to support them.[88] The strike covered an area of over 400 square miles;[89] Chavez divided the picketers among four quadrants, each with a mobile crew led by a captain.[90] As the picketers urged those who continued to work to join them on strike, the growers sought to provoke and threaten the strikers. Chavez insisted that the strikers must never respond with violence.[91] The picketers also protested outside strike-breakers' homes,[92] with the strike dividing many families and breaking friendships.[93] Police monitored the protests, photographing many of those involved;[94] they also arrested various strikers.[95] To raise support for those arrested, Chavez called for donations at a speech in Berkeley's Sproul Plaza in October; he received over $1000.[96] Many growers considered Chavez a communist,[97] and the FBI launched an investigation into both him and the NFWA.[98]

In December, the United Automobile Workers (UAW) president Walter Reuther joined Chavez in a pro-strike protest march through Delano.[99] This was the first time that the strike attracted national media attention.[100] Reuther then pledged that the UAW would donate $5000 a month to be shared between the AWOC and NFWA.[100] Chavez also met with representatives of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), which became an important ally of the strikers.[93] Influenced by the African American civil rights movement's successful use of boycott campaigns, Chavez decided to launch his own, targeting companies which owned Delano vineyards or sold grapes grown there. The first target selected, in December 1965, was the Schenley liquor company, which owned one of the area's smaller vineyards.[101] Chavez organized pickets to take place in other cities where Schenley's grapes were being delivered for sale.[102]

By 1965, Chavez was aware that the numbers joining the picket lines had declined; although hundreds of pickers had initially struck, some had returned to their jobs, found employment elsewhere, or moved away from Delano. To keep the pickets going, Chavez invited left-wing activists from elsewhere to join them; many, particularly university students, came from the San Francisco Bay Area.[103] Recruitment was fuelled by coverage of the strike in the SNCC's newspaper, The Movement, and the Marxist People's World newspaper.[104] By late fall 1966, a protest camp had formed in Delano, opening its own medical clinic and children's nursery.[105] Protesters were entertained by Luis Valdez's El Teatro Campesino, which put on skits with a political message.[106] Within the protest movement there were some tensions between the striking farm-workers and the influx of student radicals.[105]

Growing success: 1966–1967

— Luis Valdez's "Plan de Delano", read aloud at each stop along Chavez's march to Sacramento[107]

In March 1966, the U.S. Senate Committee on Labor and Public Welfare's Subcommittee on Migratory Labor held three hearings in California. The third, which took place in Delano, was attended by Senator Robert F. Kennedy, who toured a labor camp with Chavez and addressed a mass meeting.[108] As the strike began to flag in winter, Chavez decided on a march of 300 miles to the state capitol at Sacramento. This would pass through dozens of farmworker communities and attract attention for their cause.[109] In March,[110] the procession started out with about fifty marchers who left Delano.[111]

Chavez imbued the march with Roman Catholic significance. Marchers carried crucifixes and a banner of the Virgin of Guadalupe and used the slogan "Peregrinación, Penitencia, Revolución."[112] Portraying the march as an act of penance, he argued that the image of his personal suffering—his feet became painful and for part of the journey he had to walk with a cane—would be useful for the movement.[113] At each stop, they read aloud a "Plan de Delano" written by Valdez, deliberately echoing the "Plan de Alaya" of Mexican revolutionary Emiliano Zapata.[114] At Easter, the marchers arrived in Sacramento, where over 8000 people amassed in front of the state capitol. Chavez briefly addressed the crowd.[115]

During the march, Chavez had been approached by Schenley's lawyer, Sidney Korshak. They agreed to contract negotiations within 60 days. Chavez then declared an end to the Schenley boycott; instead, the movement would switch the boycott to the DiGiorgio Corporation, a major Delano land owner.[116] DiGiorgio then called an election among their vineyard workers, hoping to challenge the NFWA's influence.[117] A more conservative union, the International Brotherhood of Teamsters, were competing against the NFWA in the DiGiorgio workers' election.[118] After DiGiorgio altered the terms of the election to benefit a Teamster victory, Chavez removed the NFWA from the ballot and urged his supporters to abstain. When the vote took place in June 1966, nearly half of eligible workers abstained, allowing a Teamster victory.[119] Chavez then appealed to Jerry Brown, the Governor of California, to intervene. Brown agreed, wanting the endorsement of the Mexican American Political Association. He declared the DiGiorgio election invalid and called for an August rerun to be supervised by the American Arbitration Association.[120] On 1 September, Chavez's union was declared the victor in the second election.[121] DiGiorgio subsequently largely halted grape production in Delano.[122] The focus then shifted to Giumarra, the largest grape grower in the San Joaquin Valley.[123] In August 1967, Chavez announced a strike against them followed by a boycott of their grapes.[124]

An agreement was reached that Chavez's NFWA would merge with the AWOC, resulting in a new United Farm Workers Organizing Committee (UFWOC).[125] AWOC's Larry Itliong became the new group's assistant director,[126] although soon felt marginalised by Chavez.[127] UFWOC was also made an organizing committee of the AFL-CIO; this ensured that it would become a formal part of the U.S. labor movement and would receive a monthly subsidy.[125] Not all of Chavez's staff agreed with the merger; many of its more left-wing members mistrusted the growing links with organized labor, particularly due to the AFL-CLIO's anti-communist views.[128] UFWOC was plagued by ethnic divisions between its Filipino and Mexican members,[129] although continued to attract new volunteers, the majority Anglos brought into the movement via left-wing and religious groups or as part of social service internships.[130] Chavez brought new people, such as LeRoy Chatfield, Marshall Ganz, and the lawyer Jerry Cohen, into his inner circle.[131] His old friend, Fred Ross, had also joined.[132] Soon, the secretary-treasurer Antonio Orendain was left as the only Mexican migrant in the union's senior ranks.[127]

In June 1967, Chavez launched his first purge of the union to remove those he deemed disruptive or disloyal to his leadership. His cover story was that he wanted to eject members of the Communist Party and related far-left groups, although the FBI's report at the time found no evidence of communist infiltration of the union.[133] Some longstanding members, such as Esher, left because they disapproved of these purges.[134] Tensions between Chavez and the Teatro had been building for some time; the Teatro's members were among those highly critical of the union's new links with the AFL-CLIO.[135] Chavez was concerned that the Teatro had become a rival to his prominent standing in the movement and was questioning his actions.[136] Chavez asked the Teatro to disband, at which it split from the union and went on a tour of the U.S.[137]

Forty Acres and public fasts: 1967–68

The union purchased land known as The Forty Acres for their new headquarters.[134] Chavez hoped for it to be a "spiritual" center where union members would relax; he designed it to have a swimming pool, a chapel, a market, and a gas station, as well as gardens with outdoor sculptures.[138] He wanted the main building to be decorated inside with Gandhi quotations in English and Spanish.[138] Meanwhile, Chavez was increasingly concerned that his supporters might turn to violence.[139] Members had engaged in the destruction of property, something they regarded as not breaching the movement's ethos on non-violence.[140] Chavez's cousin Manuel had tampered with refrigerator units on trains, so that grapes being shipped out of Delano spoiled before reaching their destination;[140] Chavez noted that "He's done all the dirty work for the union. There's a lot of fucking dirty work, and he did it all."[140] In February 1968, the Giumarra company obtained a contempt citation against the union, claiming that its members had used threatening and intimidating behavior against its employees and had placed roofing nails at the entrances to its ranches.[141]

In February 1968, Chavez began a fast; he publicly stated that in doing so he was reaffirming his commitment to peaceful protest and presented it as a form of penance.[142] He stated that he would remain at Forty Acres for the duration of his fast, which at this point had only a gas station there.[143] Many members of the union were critical of what they saw as a stunt; Itliong was annoyed that Chavez had not consulted the union's board before making his declaration. The union introduced a motion urging Chavez to cancel his plan, although this failed.[143] Father Mark Day announced that a mass would he held every night at Forty Acres. These attracted many of Chavez's supporters, with the gas station decorated as an impromptu shrine.[144] Sympathetic Protestant clergy and Jewish rabbis also spoke at these masses.[145] After three weeks, Chavez's doctors urged him to end the fast. He agreed to do so at a public event on 10 March.[146] He invited Kennedy to be the guest of honor at this event. Kennedy arrived at the event, which was attended by thousands of observers as well as the national press, and there they shared bread.[147]

— Martin Luther King's telegram to Chavez after the latter announced his fast in February 1968[148]

Not long after, Kennedy announced his candidacy to be the Democratic Party's next presidential candidate. He asked Chavez to run as a delegate in the California primary.[149] Throughout May, Chavez travelled across California, urging farmworkers and registered Democrats to back Kennedy.[150] His activism was a contributing factor to Kennedy's victory in that state.[151] It was at the victory celebration in Los Angeles that Kennedy was assassinated on June 5.[151] Chavez then attended Kennedy's New York funeral as a pallbearer.[152] Kennedy's assassination came two months after that of Martin Luther King, generating growing concerns among the union that Chavez would also be targeted by those who opposed him.[153]

In May, Chavez appeared on the Today television show and announced a boycott of all grapes produced in California.[154] The boycotters' message was that consumers should avoid buying California grapes so that farmworkers would get better wages and working conditions.[154] Supporters across the country picketed stores selling California grapes and disrupted annual meetings of several supermarket chains.[154] Chavez hoped that by putting pressure on the supermarkets, they in turn would pressure the grape growers to give in to strikers' demands.[154] The growers hired a public relations firm to counteract the boycott, warning stores that if they gave in to the boycott they would soon be faced with similar boycotts for many other products.[155] The growers also turned to the newly elected Governor of California, Ronald Reagan, who in turn sought the support of the Teamsters.[156]

Chavez's back pain worsened and in September 1968 he was hospitalised at O'Connor Hospital in San Jose.[157] He followed this with a recuperation stay at St Anthony's Seminary in Santa Barbara.[158] He returned home, but finding it too crowded moved in to Forty Acres.[158] Due to a donation from the United Auto Workers, the union had erected an office and meeting hall here, with a trailer being used as a medical clinic; it was still far from Chavez's original vision.[159] He used his image of physical suffering as a tactic in his cause, although some of his inner circle thought his pain to be at least partially psychosomatic.[160] By 1968, Chavez was a national celebrity.[152] Journalists increasingly approached him for interviews; he granted particularly close access to Peter Matthiessen and Jacques E. Levy, both of whom wrote favorable books about him.[161] In July 1969, Chavez's portrait appeared on the front of Time magazine.[162] Within the union, personal loyalty to Chavez became increasingly important;[163] tensions between him and Itliong grew.[164]

Travels: 1969–

In March 1969, the doctor Janet Travell visited Chavez and determined that fused vertebra were the source of his back pain. She prescribed various exercises and other treatments which he found eased his pain.[165]

Between September and December, Chavez travelled the country in a Winnebago speaking at dozens of fundraisers and rallies for the grape boycott.[166] At a speech in Washington D.C., he came out publicly against U.S. involvement in the Vietnam War, a topic he had previously avoided speaking on, because his son Fernando had been arrested as a conscientious objector.[167]

In the late 1970s, Chavez also sought to advance his control over the California Rural Legal Assistance (CRLA), a group which advocated for farmworkers. Chavez demaded that the CRLA make its staff available for union work and that it would allow the union's attorneys to decide which cases the CRLA would pursue. Under the leadership of Cruz Reynoso, a former Chavez ally, the CRLA refused.[168] Pawel believed that these attempts reflected Chavez's desire to be seen as the only voice for farmworkers.[169]

Chavez negotiated with Lionel Steinberg, a grape grower in the Coachella area. They signed contracts allowing Steinberg's products to be sold with a union logo on them, indicating that they would be exempt from the boycott.[170] Other Coachella growers regarded Steinberg as a traitor for negotiating with Chavez but ultimately followed suit, resulting in contracts being signed with the union.[170] In July 1979, the Delano growers agreed to negotiate.[171] Chavez insisted that their negotiations also cover issues at the Delano High School, where several pupils, including is own daughter Eloise, had been suspended or otherwise disciplined for protesting in support of the boycott.[172] On July 29, 1970, the Delano growers signed contracts with the union at the Forty Acres Hall, in front of press.[173]

Activism, 1952–1976

These activities led to similar movements in Southern Texas in 1966, where the UFW supported fruit workers in Starr County, Texas, and led a march to Austin, in support of UFW farm workers' rights. In the Midwest, Chavez's movement inspired the founding of two midwestern independent unions: Obreros Unidos in Wisconsin in 1966, and the Farm Labor Organizing Committee (FLOC) in Ohio in 1967. Former UFW organizers would also found the Texas Farm Workers Union in 1975.

In 1970, Chavez began a fast of "thanksgiving and hope" to prepare for pre-arranged civil disobedience by farm workers.[174] Also in 1972, he fasted in response to Arizona's passage of legislation that prohibited boycotts and strikes by farm workers during the harvest seasons.[174] These fasts were influenced by the Catholic tradition of penance and by Mohandas Gandhi's fasts and emphasis of nonviolence.[175]

Immigration

The UFW during Chavez's tenure was committed to restricting import of immigrant labor. On a few occasions, concerns that illegal immigrant labor would undermine UFW strike campaigns led to a number of controversial events, which the UFW describes as anti-strikebreaking events, but which have also been interpreted as being anti-immigrant. In 1969, Chavez and members of the UFW marched through the Imperial and Coachella Valleys to the border of Mexico to protest growers' use of illegal immigrants as strikebreakers. Joining him on the march were Reverend Ralph Abernathy and U.S. Senator Walter Mondale.[176] In its early years, the UFW and Chavez went so far as to report illegal immigrants who served as strikebreaking replacement workers (as well as those who refused to unionize) to the Immigration and Naturalization Service.[177][178][179][180][181] In 1973, the United Farm Workers set up a "wet line" along the United States-Mexico border to prevent Mexican immigrants from entering the United States illegally and potentially undermining the UFW's unionization efforts.[182] During one such event, in which Chavez was not involved, some UFW members, under the guidance of Chavez's cousin Manuel, physically attacked the strikebreakers after peaceful attempts to persuade them not to cross the border failed.[183][184][185]

In 1973, the UFW was one of the first labor unions to oppose proposed employer sanctions that would have prohibited hiring illegal immigrants. Later during the 1980s, while Chavez was still working alongside Huerta, he was key in getting the amnesty provisions into the 1986 federal immigration act.[186]

Legislative campaigns

Chavez had long preferred grassroots action to legislative work, but in 1974, propelled by the recent election of the pro-union Jerry Brown as governor of California, as well as a costly battle with the Teamsters union over the organizing of farmworkers, Chavez decided to try to work toward legal victories.[187] Once in office, Brown's support for the UFW cooled.[187] The UFW decided to organize a 110-mile (180 km) march by a small group of UFW leaders from San Francisco to the E & J Gallo Winery in Modesto. Just a few hundred marchers left San Francisco on February 22, 1975. By the time they reached Modesto on March 1, however, more than 15,000 people had joined the march en route.[187] The success of the Modesto march garnered significant media attention, and helped convince Brown and others that the UFW still had significant popular support.[187]

On June 4, 1975, Governor Brown signed into law the California Agricultural Labor Relations Act (ALRA), which established collective bargaining for farmworkers. The act set up the California Agricultural Labor Relations Board (ALRB) to oversee the process.

In mid-1976, the ALRB ran out of its budgeted money for the year, as a result of a massive amount of work in setting up farmworker elections. The California legislature refused to allocate more money, so the ALRB closed shop for the year.[188] In response, Chavez gathered signatures in order to place Proposition 14 on the ballot, which would guarantee the right of union organizers to visit and recruit farmworkers, even if it meant trespassing on private property controlled by farm owners. The proposition went before California voters in November 1976, but was defeated by a 2–1 margin.[188]

Setbacks and a change of direction, 1976–1988

As a result of the failure of Proposition 14, Chavez decided that the UFW suffered from disloyalty, poor motivation, and lack of communication.[188] He felt that the union needed to turn into a "movement".[189] He took inspiration from the Synanon community of California (which he had visited previously), which had begun as a drug rehabilitation center before turning into a New Age religious organization.[190] Synanon had pioneered what they referred to as "the Game", in which each member would be singled out in turn to receive harsh, profanity-laced criticism from the rest of the community.[190] Chavez instituted "the Game" at UFW, having volunteers, including senior members of the organization, receive verbal abuse from their peers.[190] He also fired many members, whom he accused of disloyalty; in some cases he accused volunteers of being spies for either the Republican Party or the Communists.[189]

In 1977, Chavez attempted to reach out to Filipino-American farmworkers in a way that ended up backfiring. Acting on the advice of former UFW leader Andy Imutan, Chavez met with then-President of the Philippines Ferdinand Marcos in Manila and endorsed the regime, which was seen by human rights advocates and religious leaders as a vicious dictatorship. This caused a further rift within the UFW, which led to Philip Vera Cruz's resignation from the organization.[191][192][193][194]

During this time, Chavez also clashed with other UFW members about policy issues, including the possible creation of local unions for the UFW, which was typical for national unions but which Chavez was firmly against, on the grounds that it detracted from his vision for the UFW as a movement.[188] During this period, dissent within the union was removed, with some attacked by Chavez claiming they were communist infiltrators.[195]

By the end of the 1970s, only one member of the UFW's original board of directors remained in place.[188] Still, before the turn of the 1980s decade, Chavez's tactics had forced growers to recognize the UFW as the bargaining agent for 50,000 field workers in California and Florida. Meanwhile, membership in the UFW union had been in decline and by the mid-1980s it had dwindled to around 15,000.[196] In the 1980s, with the UFW declining, Chavez got into real-estate development; some of the development projects he was involved with used non-union construction workers, which The New Yorker later termed an "embarrassment".[189]

In 1988, Chavez attempted another grape boycott, to protest the exposure of farmworkers to pesticides. Bumper stickers reading "NO GRAPES" and "UVAS NO" (the translation in Spanish) were widespread.[197] However, the boycott failed. As a result, Chavez undertook what was to be his last fast. He fasted for 35 days before being convinced by others to start eating again. He lost 30 pounds during the fast, and it caused health problems that may have contributed to his death.[189]

Death

Chavez died on April 23, 1993, of unspecified natural causes in San Luis, Arizona, in the home of former farm worker and longtime friend Dofla Maria Hau.[25] Chavez was in Arizona helping UFW attorneys defend the union against a lawsuit. Shortly after his death, his widow, Helen Chavez, donated his black nylon union jacket to the National Museum of American History, a branch of the Smithsonian.[198]

Chavez is buried at the National Chavez Center, on the headquarters campus of the United Farm Workers of America (UFW), at 29700 Woodford-Tehachapi Road in the Keene community of unincorporated Kern County, California.[199]

He received belated full military honors from the US Navy at his graveside on April 23, 2015, the 22nd anniversary of his death.[200]

Personal life

— Cesar Chavez, 1984[201]

When Chavez returned home from his service in the military in 1948, he married his high school sweetheart, Helen Fabela. The couple moved to San Jose, California.[25] With his wife, he had eight children: Fernando (b.1949), Sylvia (b.1950), Linda (b.1951), Eloise (b.1952), Anna (b.1953), Paul (b.1957), Elizabeth (b.1958), and Anthony (b.1958).[202] Helen avoided the limelight, a trait which Chavez admired.[203] While he led the union, she focused on raising the children, cooking, and housekeeping.[204] Chavez's relationship with his eldest son, Fernando, was strained; he was frustrated at what he saw as his son's interest in becoming middle-class.[205]

Chavez expressed traditional views on gender roles and was little influenced by the second wave feminism that was contemporary with his activism.[203] In his movement, men took almost all the senior roles, with women largely being confined to background roles as secretaries, nurses, or in child-care; the main exception was Huerta.[203] Chavez had a close working relationship with Huerta. They became mutually dependent, and although she did not hesitate to raise complaints with him, she also usually deferred to him.[206] He never had close friendships outside of his family, believing that friendships distracted from his political activism.[207]

Physically, Chavez was short,[45] and had jet black hair.[208] He was quiet,[71] and Bruns described him as being "outwardly shy and unimposing".[208] Like many farm laborers, he experienced severe back pain throughout his life.[208] He could be self-conscious about his lack of formal education and was uncomfortable interacting with affluent people.[71] When speaking with reporters, he sometimes mythologised his own life story.[209] Chavez was not a great orator; according to Pawel, "his power lay not in words, but in actions".[210] She noted that he was "not an articulate speaker",[45] and similarly, Bruns observed that he "had no special talent as a public speaker".[211] He was softly-spoken,[212] and according to Pawel had an "informal, conversational style",[213] and was "good at reading people".[45]

Pawel stated that as a leader, Chavez was both "charming, attentive, and humble" as well as being "single-minded, demanding, and ruthless".[214] When he wanted to criticise one of his volunteers or staff members he usually did so in private but on occasion could berate them in a public confrontation.[80] He described his own life's work as a crusade against injustice,[210] and displayed a commitment to self-sacrifice.[215] Pawel thought that "Chavez thrived on the power to help people and the way that made him feel".[45] Ross, who was a friend and colleague of Chavez's for many years, noted that "He would do in thirty minutes what it would take me or somebody else thirty days".[119]

Chavez was a Roman Catholic whose faith strongly influenced both his social activism and his personal outlook.[19][216][217][218] Throughout his career as an activist, he received strong ecumenical support.[79] In 1970 he became a vegetarian.[219] He later became a vegan, both because he believed in animal rights and also for his health.[220][221][222] Chavez had a love of the music of Duke Ellington and Big Band music;[26] among his favourite foods were traditional Mexican and Chinese cuisines.[223] He was also a keen gardener, making his own compost and growing vegetables.[224] For much of his adult life he kept German shepherd dogs for personal protection.[225] Chavez preserved many of his notes, letters, the minutes of meetings, as well as tape recordings of many interviewers, and at the encouragement of Philip P. Mason donated these to the Walter P. Reuther Library, where they are kept.[226] He disliked telephone conversations, suspecting that his phone line was bugged.[227]

Political views

Chavez described his movement as promoting "a Christian radical philosophy".[138] According to Chavez biographer Roger Bruns, he "focused the movement on the ethnic identity of Mexican Americans" and on a "quest for justice rooted in Catholic social teaching".[228] Chavez saw his fight for farmworkers' rights as a symbol for the broader cultural and ethnic struggle for Mexican Americans in the United States.[223] Chavez saw parallels in the way that African Americans were treated in the United States to the way that he and his fellow Mexican Americans were treated.[229] He absorbed many of the tactics that African American civil rights activists had employed throughout the 1960s, applying them to his own movement.[229]

Chavez abhorred poverty and wanted to ensure a better standard of living for the poor.[230] He was concerned that, as he had seen with the CSO, individuals moving out of poverty adopted middle-class valued; he viewed the middle classes with contempt.[230] He recognised that union activity was not a long-term solution to poverty across society and suggested that forming co-operatives therefore might be the best solution.[230] In Chavez's view, workers' cooperatives offered a middle ground economic choice between capitalism and the state socialism of Marxist-Leninist countries.[231]

Chavez kept a large portrait of Gandhi in his office,[232] alongside another of Martin Luther King and busts of both John F. Kennedy and Abraham Lincoln.[159] Influenced by the ideas of Gandhi and King, Chavez emphasized non-violent confrontation as a tactic.[89] He was interested not only on Gandhi's ideas on non-violence but also in the Indian's voluntary embrace of poverty, his use of fasting, and his ideas about community.[122] Chavez was interested in Gandhi's ideas about sacrifice, noting that "I like the idea of sacrifice to do things. If they are done that way they are more lasting. If they cost more, then you will value them more."[122]

On organization and leadership

Chavez felt that he had to be both the leader and the organizer-in-chief of his movement because only he had the necessary commitment to the cause.[233] He was interested in power and how to use it; although his role model in this was Gandhi, he also studied the ideas about power by Niccolò Machiavelli, Adolf Hitler, and Mao Zedong, drawing ideas from each.[122] Chavez repeatedly referred to himself as a community organizer rather than as a labor leader and underscored that distinction.[100] He was ambivalent about the national labor movement.[100] He personally disliked many of the prominent figures within the American labor movement but, as a pragmatist, recognized the value of working with organized labor groups.[129]

Pawel described Chavez as "the ultimate pragmatist".[163] He dominated the movement he led. In 1968, Fred Hirsch noted that "one thing which characterizes Cesar's leadership is that he takes full responsibility for as much of the operation as he is physically capable of. All decisions are made by him."[234] Itlions noted that "Cesar is afraid that if he shares the authority with the people[…] they might run away from him."[234] He divided members of movements such as his into three groups: those that achieved what they set out to do, those that worked hard but failed what they set out to do, and those that were lazy. He thought that the latter needed to be expelled from the movement.[235] He highly valued individuals who were loyal, efficient, and took the initiative.[236] Explaining his attitudes toward activism, he told his volunteers that "nice guys throughout the ages have done very little for humanity. It isn't the nice guy who gets things done. It's the hardheaded guy."[235] He admitted that he could be "a real bastard" when dealing with movement members.[237]

Reception and legacy

— Roger Bruns, 2005[211]

.jpg)

During his lifetime, many of Chavez's supporters idolised him, engaging in a form of hero worship.[207] These supporters were known as "Chavistas."[163] Many growers were suspicious of him. John Giumarra Jr, of the Giumarra company, called Chavez a "New Left guerrilla", someone who wanted to topple "the established structure of American democracy."[226]

Pawel referred to Chavez as "an improbable idol in an era of telegenic leaders and charismatic speakers".[210] The historian Nelson Lichtenstein commented that Chavez's UFW oversaw "the largest and most effective boycott [in the United States] since the colonists threw tea into Boston Harbor."[238] Lichtenstein also stated that Chavez had become "an iconic, foundational figure in the political, cultural, and moral history" of the Latino American community.[239]

When the Democratic Party candidate Barack Obama was campaigning for the presidency in 2008, he used Sí se puede—translated into English as "Yes we can"—as one of his main campaign slogans.[240] When Obama was seeking re-election in 2012, he visited Chavez's grave and placed a rose upon it, also declaring his Union Headquarters to be a national monument.[240] Chavez's work has continued to exert influence on later activists. For instance, in his 2012 article in the Journal of the Society of Christian Ethics, Kevin J. O'Brien argued that Chavez could be "a vital resource for contemporary Christian ecological ethics".[241] O'Brien argued that it was both Chavez's focus on "the moral centrality of human dignity" as well as his emphasis on sacrifice that could be of use by Christians wanting to engage in environmentalist activism.[242]

There is a portrait of Chavez in the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, D.C.[243]

In 2003, the United States Postal Service honored Chavez with a postage stamp.[244]

The American Friends Service Committee (AFSC) nominated him three times for the Nobel Peace Prize.[245]

One of Chavez's grandchildren is the professional golfer Sam Chavez.

Awards and honors

- In 1973, Chavez received the Jefferson Award for Greatest Public Service Benefiting the Disadvantaged.[246]

- In 1992, Chavez was awarded the Pacem in Terris Award, a Catholic award meant to honor "achievements in peace and justice".[247]

- On September 8, 1994, Chavez was presented posthumously with the Presidential Medal of Freedom by President Bill Clinton. The award was received by his widow, Helen Chavez.

- On December 6, 2006, California governor Arnold Schwarzenegger and First Lady Maria Shriver inducted Chavez into the California Hall of Fame.[248]

- Asteroid 6982 Cesarchavez, discovered by Eleanor Helin at Palomar Observatory in 1993, was named in his memory.[249] The official naming citation was published by the Minor Planet Center on August 27, 2019 (M.P.C. 115893).[250]

- On March 31, 2013, Google celebrated his 86th birthday with a Google Doodle.[251]

Places and things named after Cesar Chavez

Across the United States, and especially in California, there have been many parks, streets, schools, libraries, university buildings and other establishments named after Chavez. In addition, the census-designated place of Cesar Chavez, Texas is named after him. Plaza de César Chávez in San Jose, California was named in 1993 after Chavez, who lived in the city for a period.

Colegio Cesar Chavez, named after Chavez while he was still alive, was a four-year "college without walls" in Mount Angel, Oregon, intended for the education of Mexican-Americans, that ran from 1973 to 1983.[252]

On May 18, 2011, Navy Secretary Ray Mabus announced that the Navy would be naming the last of 14 Lewis and Clark-class cargo ships after Cesar Chavez.[253] The USNS Cesar Chavez was launched on May 5, 2012.[254]

Monuments

In 2004, the National Chavez Center was opened on the UFW national headquarters campus in Keene by the César E. Chávez Foundation. It currently consists of a visitor center, memorial garden and his grave site. When it is fully completed, the 187-acre (0.76 km2) site will include a museum and conference center to explore and share Chavez's work.[199]

On September 14, 2011, the U.S. Department of the Interior added the 187 acres (76 ha) Nuestra Senora Reina de La Paz ranch to the National Register of Historic Places.[255]

On October 8, 2012, President Barack Obama designated the Cesar E. Chavez National Monument within the National Park system.[256]

California State University San Marcos's Chavez Plaza includes a statue to Chavez. In 2007, The University of Texas at Austin unveiled its own Cesar Chavez statue[257] on campus.

The Consolidated Natural Resources Act of 2008 authorized the National Park Service to conduct a special resource study of sites that are significant to the life of Cesar Chavez and the farm labor movement in the western United States. The study evaluated the significance and suitability of sites significant to Cesar Chavez and the farm labor movement, and the feasibility and appropriateness of a National Park Service role in the management of any of these sites.[258]

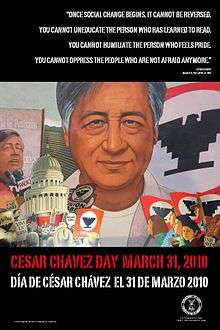

Cesar Chavez Day

Cesar Chavez's birthday, March 31, is a state holiday in California,[259] Colorado, and Texas. It is intended to promote community service in honor of Chavez's life and work. Many, but not all, state government offices, community colleges, and libraries are closed. Many public schools in the three states are also closed. Chavez Day is an optional holiday in Arizona. Although it is not a federal holiday, President Barack Obama proclaimed March 31 "Cesar Chavez Day" in the United States, with Americans being urged to "observe this day with appropriate service, community, and educational programs to honor César Chávez's enduring legacy".[260]

Other commemorations

The heavily Hispanic city of Laredo, Texas, observes "Cesar Chavez Month" during March. Organized by the local League of United Latin American Citizens, a citizens' march is held in downtown Laredo on the last Saturday morning of March to commemorate Chavez. Among those attending are local politicians and students.[261]

In the Mission District, San Francisco a "Cesar Chavez Holiday Parade" is held on the second weekend of April, in honor of Cesar Chavez. The parade includes traditional Native American dances, union visibility, local music groups, and stalls selling Latino products.[262]

In popular culture

Chavez was referenced by Stevie Wonder in the song "Black Man" from the 1976 album Songs in the Key of Life.[263]

He is referenced in the 1998 American crime drama, American History X.

The 2014 American film César Chávez, starring Michael Peña as Chavez, covered Chavez's life in the 1960s and early 1970s.[264] That same year, a documentary film, titled Cesar's Last Fast, was released.

See also

- List of civil rights leaders

- List of vegans

- Sí se puede

- Union organizer

References

Footnotes

- Elizabeth Jacobs (2006). Mexican American Literature: The Politics of Identity. Routledge. p. 13.

- Bruns 2005, p. 2; Pawel 2014, pp. 8, 10.

- Pawel 2014, p. 8.

- Bruns 2005, p. 2; Pawel 2014, p. 8.

- Bruns 2005, p. 2; Pawel 2014, p. 10.

- Pawel 2014, pp. 9–10.

- Pawel 2014, p. 10.

- Pawel 2014, pp. 8, 9.

- Pawel 2014, p. 11.

- Bruns 2005, p. 6; Pawel 2014, p. 7.

- Bruns 2005, pp. 2–3; Pawel 2014, p. 8.

- Pawel 2014, pp. 10–11.

- Pawel 2014, p. 19.

- Bruns 2005, p. 2.

- Quinones, Sam (July 28, 2011). "Richard Chavez dies at 81; brother of Cesar Chavez". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved July 30, 2011.

- Pawel 2014, p. 12.

- Bruns 2005, p. 4; Pawel 2014, pp. 13–14.

- Pawel 2014, pp. 13–14.

- Bruns 2005, p. 3.

- Bruns 2005, p. 4; Pawel 2014, p. 16.

- Pawel 2014, p. 16.

- Bruns 2005, pp. 4–5; Pawel 2014, p. 16.

- Pawel 2014, p. 17.

- Bruns 2005, p. 7.

- "The Story of Cesar Chavez". United Farm Workers. Archived from the original on March 5, 2010. Retrieved February 8, 2010.

- Pawel 2014, p. 20.

- Bruns 2005, p. 9; Pawel 2014, p. 20.

- Pawel 2014, p. 21.

- Bruns 2005, p. 10; Pawel 2014, p. 21.

- Pawel 2014, pp. 21–22.

- Bruns 2005, p. 13; Pawel 2014, p. 22.

- Bruns 2005, p. 14; Pawel 2014, p. 22.

- Pawel 2014, pp. 22–23.

- Bruns 2005, pp. 14–15, 21–23; Pawel 2014, pp. 27–28.

- Bruns 2005, p. 24; Pawel 2014, p. 28.

- Pawel 2014, p. 34.

- Pawel 2014, pp. 29–30.

- Bruns 2005, p. 16; Pawel 2014, p. 29.

- Pawel 2014, p. 35.

- Bruns 2005, p. 26; Pawel 2014, pp. 26–27.

- Pawel 2014, pp. 37–38.

- Pawel 2014, pp. 40–41.

- Pawel 2014, pp. 41–44.

- Pawel 2014, p. 45.

- Pawel 2014, p. 39.

- Pawel 2014, p. 47.

- Pawel 2014, pp. 49–50.

- Bruns 2005, p. 25.

- Pawel 2014, pp. 50–51.

- Pawel 2014, p. 52.

- Bruns 2005, p. 27; Pawel 2014, pp. 53–54.

- Pawel 2014, pp. 56–57.

- Pawel 2014, p. 104.

- Pawel 2014, pp. 57–58.

- Bruns 2005, p. 28.

- Pawel 2014, pp. 59–60.

- Pawel 2014, p. 61.

- Pawel 2014, p. 60.

- Bruns 2005, p. 29; Pawel 2014, p. 63.

- Pawel 2014, p. 63.

- Pawel 2014, p. 64.

- Pawel 2014, pp. 63, 66.

- Pawel 2014, pp. 64–65.

- Pawel 2014, p. 70.

- Pawel 2014, pp. 65–66.

- Pawel 2014, pp. 71–72.

- Bruns 2005, p. 31; Pawel 2014, pp. 77, 79.

- Pawel 2014, p. 77.

- Bruns 2005, pp. 31–32; Pawel 2014, pp. 81–82.

- Bruns 2005, p. 34; Pawel 2014, pp. 80–81.

- Pawel 2014, p. 91.

- Bruns 2005, p. 35.

- Bruns 2005, pp. 33–34; Pawel 2014, p. 81.

- Pawel 2014, pp. 82–83.

- Bruns 2005, p. 34; Pawel 2014, pp. 86–87.

- Pawel 2014, p. 88.

- Bruns 2005, p. 35; Pawel 2014, p. 88.

- Bruns 2005, p. 34; Pawel 2014, pp. 88–89.

- Bruns 2005, p. 36.

- Pawel 2014, p. 93.

- Pawel 2014, p. 94.

- Bruns 2005, p. 38; Pawel 2014, pp. 95–96.

- Pawel 2014, pp. 96–98.

- Pawel 2014, p. 99.

- Pawel 2014, p. 101.

- Bruns 2005, p. 39; Pawel 2014, p. 101.

- Pawel 2014, p. 102.

- Bruns 2005, pp. 41–43; Pawel 2014, pp. 104–107.

- Bruns 2005, p. 46.

- Pawel 2014, p. 107.

- Bruns 2005, p. 46; Pawel 2014, p. 107.

- Pawel 2014, p. 109.

- Pawel 2014, p. 118.

- Bruns 2005, p. 47.

- Bruns 2005, p. 47; Pawel 2014, p. 113.

- Pawel 2014, p. 113.

- Pawel 2014, p. 112.

- Pawel 2014, p. 114.

- Bruns 2005, p. 50; Pawel 2014, pp. 114–115.

- Pawel 2014, p. 115.

- Bruns 2005, p. 50; Pawel 2014, pp. 120–121.

- Bruns 2005, p. 50; Pawel 2014, pp. 121–122.

- Bruns 2005, p. 48; Pawel 2014, pp. 118–119.

- Pawel 2014, pp. 119–120.

- Pawel 2014, p. 120.

- Bruns 2005, p. 48.

- Bruns 2005, p. 53.

- Pawel 2014, pp. 122–123.

- Bruns 2005, p. 51; Pawel 2014, pp. 124–125.

- Bruns 2005, p. 52.

- Pawel 2014, p. 125.

- Bruns 2005, p. 51; Pawel 2014, pp. 125, 127.

- Bruns 2005, pp. 52–53; Pawel 2014, p. 127.

- Bruns 2005, p. 51.

- Bruns 2005, pp. 53–54; Pawel 2014, pp. 129–130.

- Bruns 2005, pp. 53, 55; Pawel 2014, pp. 129, 132.

- Pawel 2014, p. 133.

- Bruns 2005, p. 55; Pawel 2014, p. 134.

- Pawel 2014, p. 136.

- Pawel 2014, pp. 136–137.

- Bruns 2005, p. 56; Pawel 2014, p. 141.

- Pawel 2014, p. 157.

- Pawel 2014, p. 182.

- Pawel 2014, p. 183.

- Bruns 2005, p. 56; Pawel 2014, p. 139.

- Pawel 2014, p. 139.

- Pawel 2014, p. 145.

- Pawel 2014, pp. 139–140.

- Pawel 2014, p. 140.

- Pawel 2014, p. 149.

- Pawel 2014, pp. 144-145.

- Pawel 2014, pp. 133–134.

- Pawel 2014, p. 150.

- Pawel 2014, p. 154.

- Pawel 2014, p. 152.

- Pawel 2014, p. 153.

- Pawel 2014, pp. 152–153.

- Pawel 2014, p. 155.

- Bruns 2005, pp. 59–60.

- Pawel 2014, p. 158.

- Pawel 2014, p. 159.

- Bruns 2005, pp. 60–61; Pawel 2014, p. 159.

- Pawel 2014, p. 160.

- Bruns 2005, p. 61; Pawel 2014, p. 161.

- Pawel 2014, p. 162.

- Bruns 2005, p. 63; Pawel 2014, p. 167.

- Pawel 2014, pp. 167–168.

- Bruns 2005, pp. 61–62; Pawel 2014, p. 166.

- Pawel 2014, p. 168.

- Pawel 2014, p. 170.

- Pawel 2014, p. 171.

- Pawel 2014, p. 172.

- Pawel 2014, pp. 171, 174.

- Pawel 2014, p. 186.

- Pawel 2014, p. 188.

- Pawel 2014, pp. 186–187.

- Pawel 2014, pp. 173–174.

- Pawel 2014, p. 175.

- Pawel 2014, p. 190.

- Pawel 2014, pp. 175–176.

- Pawel 2014, pp. 172–173.

- Pawel 2014, p. 181.

- Pawel 2014, p. 177.

- Pawel 2014, pp. 176–177.

- Pawel 2014, pp. 189–190.

- Pawel 2014, p. 193.

- Pawel 2014, pp. 191–193.

- Pawel 2014, pp. 202–203.

- Pawel 2014, p. 202.

- Pawel 2014, p. 200.

- Pawel 2014, pp. 204–205.

- Pawel 2014, p. 206.

- Pawel 2014, p. 208.

- Shaw, R. (2008) Beyond the Fields: Cesar Chavez, the UFW, and the struggle for justice in the 21st century University of California Press, p. 92.

- Garcia, M. (2007) The Gospel of Cesar Chavez: My Faith in Action Sheed & Ward Publishing p. 103

- Griswold del Castillo, Richard; Garcia, Richard A. (1997). Cesar Chavez: A Triumph of Spirit. University of Oklahoma Press. pp. 89–90. ISBN 0806129573.

- Gutiérrez, David Gregory (1995). Walls and Mirrors: Mexican Americans, Mexican Immigrants and the Politics of Ethnicity. San Diego: University of California Press. pp. 97–98. ISBN 9780520916869.

UFW report undocumented.

- Irvine, Reed; Kincaid, Cliff. "Why Journalists Support Illegal Immigration". Accuracy in the Media. Retrieved June 18, 2014.

- Wells, Miriam J. (1996). Strawberry Fields: Politics, Class, and Work in California Agriculture. New York: Cornell University Press. pp. 89–90. ISBN 9780801482793.

ufw undocumented.

- Baird, Peter; McCaughan, Ed. Beyond the Border: Mexico & the U.S. Today. North American Congress on Latin America. p. 169. ISBN 9780916024376.

- Farmworker Collective Bargaining, 1979: Hearings Before the Committee on Labor Human Resources Hearings held in Salinas, Calif., April 26, 27, and Washington, D.C., May 24, 1979

- "PBS Airs Chávez Documentary", University of California at Davis – Rural Migration News.

- Etulain, Richard W. (2002). Cesar Chavez: A Brief Biography with Documents. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 18. ISBN 9780312294274.

cesar chavez undocumented.

- Arellano, Gustavo. "The year in Mexican-bashing". OC Weekly. Archived from the original on June 9, 2014. Retrieved June 18, 2014.

- Navarrette, Jr., Ruben (March 30, 2005). "The Arizona Minutemen and César Chávez". San Diego Union Tribune.

- "Cesar Chavez and UFW: longtime champions of immigration reform". United Farm Workers. Archived from the original on April 7, 2014. Retrieved June 18, 2014.

- del Castillo, Richard Griswold and Garcia, Richard A. Cesar Chavez: A Triumph of Spirit. Stillwater, Okla.: University of Oklahoma Press, 1997. ISBN 0-8061-2957-3

- Chatfield, LeRoy (2005). "A Turning Point" (PDF). LeRoy Chatfield, "Thirteen Cesar Chavez Essays". UC San Diego Library Farmworker Movement Documentation Project.

- Heller, Nathan (April 14, 2014). "Hunger Artist". The New Yorker.

- Flanagan, Caitlin (July–August 2011). "The Madness of Cesar Chavez". The Atlantic.

- Rodel Rodis (January 30, 2007). "Philip Vera Cruz: Visionary Labor Leader". Inquirer. Archived from the original on September 15, 2011. Retrieved May 18, 2011.

In one chapter of this book, Philip provides an account of his conflict with César Chávez over Philippine strongman Ferdinand Marcos. This occurred in August 1977 when Marcos extended an invitation to Chávez to visit the Philippines. The invitation was coursed through a pro-Marcos former UFW leader, Andy Imutan, who carried it to César and lobbied him to visit to the Philippines.

- Shaw, Randy (2008). Beyond the Fields: Cesar Chavez, the UFW, and the Struggle for Justice in the 21st Century. Los Angeles: University of California Press. p. 253. ISBN 978-0-520-25107-6. Retrieved May 18, 2011.

Further divisions emerged in August 1977 when Chávez was invited to visit the Philippines by the country's dictator, Ferdinand Marcos. Filipino farmworkers had played a central role in launching the Delano grape strike in 1965 (see chapter 1), and Filipino activist Philip Vera Cruz had been a top union officer since 1966.

- Pawel, Miriam (2010). The Union of Their Dreams: Power, Hope, and Struggle in César Chávez's Farm Worker Movement. New York, NY: Bloomsbury Publishing USA. p. 233. ISBN 978-1-60819-099-7. Retrieved May 18, 2011.

In the fall 1977 Chris found himself embroiled in a much more public confrontation. Chavez traveled to the Philippines, a misguided effort to reach out to Filipino workers who distrusted the union. Ferdinand Marcos hosted the UFW delegation. Chavez was quoted in the Washington Post praising the dictator's regime. Human rights advocates and religious leaders protested.

- San Juan, Epifanio (2009). Toward Filipino self-determination: beyond transnational globalization. Albany: SUNY Press. p. 83. ISBN 978-1-4384-2723-2. Retrieved May 18, 2011.

This is also what Philip Vera Cruz found when, despite his public protest, he witnessed César Chávez endorsing the vicious Marcos dictatorship in the seventies.

- Pawal, Miriam (January 10, 2006). "Decisions of Long Ago Shape the Union Today". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved September 3, 2018.

- "United Farm Workers 50th Anniversary". Religion and Ethics Newsweekly, Public Broadcasting System. June 22, 2012. Retrieved June 18, 2014.

- "Bumper Sticker Uvas No". United Farm Workers. Archived from the original on February 26, 2015.

- "César Chávez's Union Jacket". National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved July 7, 2008.

- What is the National Chávez Center?, National Chávez Center, Accessed August 8, 2009.

- "22 years after death, Cesar Chavez gets Navy funeral honors". CBS and AP. April 23, 2015. Retrieved April 23, 2015.

- Pawel 2014, pp. 2–3.

- Bruns 2005, pp. 13, 26.

- Pawel 2014, p. 146.

- Pawel 2014, pp. 146–147.

- Pawel 2014, p. 192.

- Pawel 2014, p. 92.

- Pawel 2014, p. 180.

- Bruns 2005, p. 13.

- Pawel 2014, pp. 130–131.

- Pawel 2014, p. 2.

- Bruns 2005, p. x.

- Bruns 2005, p. 26.

- Pawel 2014, p. 48.

- Pawel 2014, pp. 143–144.

- Pawel 2014, p. 50.

- Hudock, Barry (August 27, 2012). "Cesar's Choice: How America's Farm Workers got Organized". America. Retrieved December 4, 2017.

- Marco G. Proudy, César Chávez, the Catholic Bishops, and the Farmworkers' Struggle for Social Justice (Tucson, AZ: University of Arizona, 2008).

- O'Brien, Matt (March 28, 2015). "St. Cesar? San Jose leaders propose Catholic sainthood for farm labor leader". Santa Cruz Sentinel News. Retrieved December 8, 2017.

- Pawel 2014, p. 204.

- Morris, Sophie (June 19, 2009). "Can you read this and not become a vegan?". The Ecologist. London. Archived from the original on July 23, 2011. Retrieved February 25, 2011.

he remembers Cesar Chavez, the Mexican farm workers activist and a vegan

CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link) - Ramirez, Gabriel (January 4, 2006). "Vegetarians Add Some Cultural Flare to Meals". Más Magazine. Bakersfield, California. Archived from the original on July 8, 2011. Retrieved February 25, 2011.

Cesar was a vegan. He didn't eat any animal products. He was a vegan because he believed in animal rights but also for his health

CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link) - Paul Brody, Si se Puede: A Biography of Cesar Chavez, 2013, chapter 5

- Bruns 2005, p. 57.

- Pawel 2014, p. 147.

- Pawel 2014, p. 173.

- Pawel 2014, p. 189.

- Pawel 2014, p. 191.

- Bruns 2005, p. 50.

- Bruns 2005, p. 44.

- Pawel 2014, p. 195.

- Pawel 2014, p. 196.

- Bruns 2005, p. 60; Pawel 2014, p. 190.

- Pawel 2014, p. 143.

- Pawel 2014, p. 179.

- Pawel 2014, p. 144.

- Pawel 2014, p. 148.

- Pawel 2014, p. 178.

- Lichtenstein 2013, p. 144.

- Lichtenstein 2013, p. 143.

- Pawel 2014, p. 3.

- O'Brien 2012, p. 151.

- O'Brien 2012, p. 152.

- database of portraits in the National Portrait gallery – Cesar Chavez. Accessed March 20, 2009.

- Cesar E. Chavez U.S. Stamp Gallery

- "Nobel Peace Prize Nominations". American Friends Service Committee. Retrieved March 5, 2013.

- "National Winners". Jefferson Awards. Archived from the original on November 24, 2010. Retrieved June 18, 2014.

- "Pacem In Terris (Peace On Earth) Award Recipients". Diocese of Davenport. Archived from the original on July 25, 2011. Retrieved June 1, 2011.

- "César Chávez Inductee Page". California Hall of Fame List of 2006 Inductees. The California Museum for History, Women, and the Arts. Archived from the original on December 5, 2009. Retrieved September 8, 2009.

- "JPL Small-Body Database Browser: 6982 Cesarchavez (1993 UA3)" (2019-09-17 last obs.). Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Retrieved September 25, 2019.

- "MPC/MPO/MPS Archive". Minor Planet Center. Retrieved September 25, 2019.

- "Cesar Chavez's 86th Birthday". Google. March 31, 2013.

- Baer, April (July 17, 2012). "What Is César Chávez's Connection To Oregon?". Oregon Public Broadcasting (OPB). Retrieved March 5, 2013.

- "Navy names new ship for Cesar Chavez". Navy Times. Associated Press. May 18, 2011. Retrieved May 18, 2011.

- "Navy To Christen And Launch USNS Cesar Chavez On May 5". KPBS. May 3, 2012. Retrieved October 17, 2012.

- Simon, Richard (September 15, 2011). "César Chávez's Home Is Designated National Historic Site". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved September 16, 2011.

- Madhani, Aamer (October 8, 2012). "Obama announces César Chávez monument". USA Today. Retrieved October 8, 2012.

- "Cesar Chavez Statue Unveiled on West Mall of University of Texas at Austin Campus". UT News. The University of Texas at Austin. October 9, 2007. Archived from the original on March 31, 2017. Retrieved March 31, 2017.

- Cesar Chavez Special Resource Study and Environmental Assessment. San Francisco, CA: National Park Service, Pacific West Region, U.S. Department of the Interior, 2012.

- http://www.cpuc.ca.gov/General.aspx?id=6442455761

- "Presidential Proclamation: César Chávez Day" (Press release). The White House. March 30, 2011. Retrieved March 5, 2013.

- Gabriela A. Trevino, "Chavez's March for Justice observed", Laredo Morning Times, March 30, 2014, p. 3A

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on June 19, 2017. Retrieved December 6, 2018.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Rodman, Andrew (July 6, 2016). "Power Grape: Cesar Chavez's Labor Legacy". In Good Tilth. Archived from the original on August 26, 2016. Retrieved August 24, 2016.

- Garcia, Matt (April 2, 2014). "What the New Cesar Chavez Film Gets Wrong About the Labor Activist". Smithsonian.

Bibliography

- Bruns, Roger (2005). Cesar Chavez: A Biography. Westport, CT: Greenwood. ISBN 9780313334528.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lichtenstein, Nelson (2013). "Introduction: Symposium on Cesar Chavez and the United Farm Workers". International Labor and Working-Class History (83): 143–145. doi:10.1017/S014754791300001X.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- O'Brien, Kevin J. (2012). ""La Causa" and Environmental Justice: César Chávez as a Resource for Christian Ecological Ethics". Journal of the Society of Christian Ethics. 32 (1): 151–168. JSTOR 23562893.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Pawel, Miriam (2014). The Crusades of Cesar Chavez: A Biography. New York: Bloomsbury Press. ISBN 978-1-60819-710-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading

- Bardacke, Frank. Trampling Out the Vintage: Cesar Chavez and the Two Souls of the United Farm Workers. New York and London: Verso 2011. ISBN 978-1-84467-718-4 (hbk.)

- Bardacke, Frank. "Cesar's Ghost: Decline and Fall of the U.F.W.", The Nation (July 26, 1993) online version

- Bruns, Roger. Cesar Chavez: A Biography (2005) excerpt and text search

- Burt, Kenneth C. The Search for a Civic Voice: California Latino Politics (2007).

- Dalton, Frederick John. The Moral Vision of Cesar Chavez (2003) excerpt and text search

- Daniel, Cletus E. "Cesar Chavez and the Unionization of California Farm Workers." ed. Dubofsky, Melvyn and Warren Van Tine. Labor Leaders in America. University of IL: 1987.

- Etulain, Richard W. Cesar Chavez: A Brief Biography with Documents (2002), 138pp; by a leading historian. excerpt and text search

- Ferriss, Susan, and Ricardo Sandoval, eds. The Fight in the Fields: Cesar Chavez and the Farmworkers Movement (1998) excerpt and text search

- Griswold del Castillo, Richard, and Richard A. Garcia. Cesar Chavez: A Triumph of Spirit (1995). (Highly favorable treatment.)

- Hammerback, John C., and Richard J. Jensen. The Rhetorical Career of Cesar Chavez. (1998).

- Jacob, Amanda Cesar Chavez Dominates Face Sayville: Mandy Publishers, 2005.

- Jensen, Richard J., Thomas R. Burkholder, and John C. Hammerback. "Martyrs for a Just Cause: The Eulogies of Cesar Chavez", Western Journal of Communication, Vol. 67, 2003. online edition

- Johnson, Andrea Shan. "Mixed Up in the Making: Martin Luther King, Jr., Cesar Chavez, and the Images of Their Movements". Ph.D dissertation U. of Missouri, Columbia 2006. 503 pp. DAI 2007 67(11): 4312-A. DA3242742. Fulltext: ProQuest Dissertations & Theses.

- LaBotz, Dan. Cesar Chavez and La Causa (2005), a short scholarly biography.

- León, Luis D. "Cesar Chavez in American Religious Politics: Mapping the New Global Spiritual Line." American Quarterly 2007 59(3): 857–881. ISSN 0003-0678. Fulltext: Project Muse.

- Levy, Jacques E. and Cesar Chavez. Cesar Chavez: Autobiography of La Causa. (1975). ISBN 0-393-07494-3.

- Matthiessen, Peter. Sal Si Puedes (Escape If You Can): Cesar Chavez and the New American Revolution, (2nd ed. 2000) excerpt and text search

- Meister, Dick and Anne Loftis. A Long Time Coming: The Struggle to Unionize America's Farm Workers, (1977).

- Orosco, Jose-Antonio. Cesar Chavez and the Common Sense of Nonviolence (2008).

- Prouty, Marco G. Cesar Chavez, the Catholic Bishops, and the Farmworkers' Struggle for Social Justice (University of Arizona Press; 185 pages; 2006). Analyzes the church's changing role from mediator to Chavez supporter in the farmworkers' strike that polarized central California's Catholic community from 1965 to 1970; draws on previously untapped archives of the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops.

- Ross, Fred. Conquering Goliath : Cesar Chavez at the Beginning. Keene, California: United Farm Workers: Distributed by El Taller Grafico, 1989. ISBN 0-9625298-0-X.

- Soto, Gary. Cesar Chavez: a Hero for Everyone. New York: Aladdin, 2003. ISBN 0-689-85923-6 and ISBN 0-689-85922-8 (pbk.)

- Taylor, Ronald B. Chavez and the Farm Workers (1975) online edition

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to César Chávez. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Cesar Chavez |

| Library resources about Cesar Chavez |

| By Cesar Chavez |

|---|

- UFW Office of the President: César Chávez Records contains over 100 linear feet of archival material documenting Chávez's beginnings with the CSO and the formative years of the NFWA, United Farm Workers Organizing Committee, and the UFW as well as some milestones in his personal life. The records range from 1947–1984 and include boycott materials, correspondence, reports, diaries, memos and other materials. The Walter P. Reuther Library serves as the official archival repository of the United Farm Workers, and holds various collections related to Chávez and the union including photographs, audio, and motion picture recordings.

- "The Story of Cesar Chavez", United Farmworker's official biography of Chavez.

- César E. Chávez Chronology, County of Los Angeles Public Library.

- Five Part Series on Cesar Chavez, Los Angeles Times, Kids' Reading Room Classic, October 2000.

- "The study of history demands nuanced thinking", Miriam Pawel from the Austin American-Statesman, 2009/7/17. A caution that histories of Chavez and the UFW should not be hagiography, nor be suppressed, but taught "wikt:warts and all"

- The Fight in the Fields: Cesar Chavez and the Farmworker's Struggle, PBS Documentary.

- Farmworker Movement Documentation Project

- New York Times obituary, April 24, 1993

- Walter P. Reuther Library – President Clinton presents Helen Chavez with the Presidential Medal of Freedom, 1994

- Jerry Cohen Papers in the Archives & Special Collections at Amherst College. Cohen was General Counsel of the United Farm Workers of America and personal attorney of Cesar Chavez from 1967–1979.

- Cesar Chavez's FBI files, hosted at the Internet Archive: Parts 1 and 2, Part 3, Parts 4 and 5, Parts 6 and 7