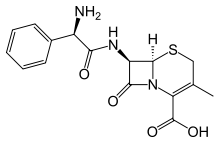

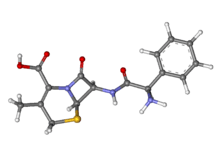

Cefalexin

Cefalexin, also spelled cephalexin, is an antibiotic that can treat a number of bacterial infections.[4] It kills gram-positive and some gram-negative bacteria by disrupting the growth of the bacterial cell wall.[4] Cefalexin is a beta-lactam antibiotic within the class of first-generation cephalosporins.[4] It works similarly to other agents within this class, including intravenous cefazolin, but can be taken by mouth.[5]

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /ˌsɛfəˈlɛksɪn/ |

| Trade names | Keflex, Ceporex, others[1] |

| Other names | cephalexin (BAN UK), cephalexin (USAN US) |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a682733 |

| License data |

|

| Pregnancy category | |

| Routes of administration | by mouth |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | Well absorbed |

| Protein binding | 15% |

| Metabolism | 80% excreted unchanged in urine within 6 hours of administration |

| Elimination half-life | For an adult with normal renal function, the serum half-life is 0.6–1.2 hours[3] |

| Excretion | Renal |

| Identifiers | |

IUPAC name

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.036.142 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C16H17N3O4S |

| Molar mass | 347.39 g/mol g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Melting point | 326.8 °C (620.2 °F) |

| |

InChI

| |

| (verify) | |

Cefalexin can treat certain bacterial infections, including those of the middle ear, bone and joint, skin, and urinary tract.[4] It may also be used for certain types of pneumonia, strep throat, and to prevent bacterial endocarditis.[4] Cefalexin is not effective against infections caused by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), Enterococcus, or Pseudomonas.[4] Like other antibiotics, cefalexin cannot treat viral infections, such as the flu, common cold or acute bronchitis.[4] Cefalexin can be used in those who have mild or moderate allergies to penicillin.[4] However, it is not recommended in those with severe penicillin allergies.[4]

Common side effects include stomach upset and diarrhea.[4] Allergic reactions or infections with Clostridium difficile, a cause of diarrhea, are also possible.[4] Use during pregnancy or breast feeding does not appear to be harmful to the baby.[4][6][7] It can be used in children and those over 65 years of age.[4] Those with kidney problems may require a decrease in dose.[4]

Cefalexin was developed in 1967.[8][9][10] It was first marketed in 1969 and 1970 under the names Keflex and Ceporex, among others.[1][11] Generic drug versions are available under other trade names and are inexpensive.[4][12] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines, the safest and most effective medicines needed in a health system.[13] In 2017, it was the 102nd most commonly prescribed medication in the United States, with more than seven million prescriptions.[14][15] In Canada, it was the fifth most common antibiotic used in 2013.[16] In Australia, it is one of the top 15 most prescribed medications.[17]

Medical uses

Cefalexin can treat a number of bacterial infections including otitis media, streptococcal pharyngitis, bone and joint infections, pneumonia, cellulitis, and urinary tract infections.[4] It may be used to prevent bacterial endocarditis.[4] It can also be used for the prevention of recurrent urinary-tract infections.[4]

Cefalexin does not treat methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections.[4]

Cefalexin is a useful alternative to penicillins in patients with penicillin intolerance. For example, penicillin is the treatment of choice for respiratory tract infections caused by Streptococcus, but cefalexin may be used as an alternative in penicillin-intolerant patients.[4] Caution must be exercised when administering cephalosporin antibiotics to penicillin-sensitive patients, because cross-sensitivity with beta-lactam antibiotics has been documented in up to 10% of patients with a documented penicillin allergy.[18]

Pregnancy and breastfeeding

It is pregnancy category B in the United States and category A in Australia, meaning that no evidence of harm has been found after being taken by many pregnant women.[4][6] Use during breast feeding is generally safe.[7]

Adverse effects

The most common adverse effects of cefalexin, like other oral cephalosporins, are gastrointestinal (stomach area) disturbances and hypersensitivity reactions. Gastrointestinal disturbances include nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea, diarrhea being most common.[19] Hypersensitivity reactions include skin rashes, urticaria, fever, and anaphylaxis.[4] Pseudomembranous colitis and Clostridium difficile have been reported with use of cefalexin.[4]

Signs and symptoms of an allergic reaction include rash, itching, swelling, trouble breathing, or red, blistered, swollen, or peeling skin. Overall, cefalexin allergy occurs in less than 0.1% of patients, but it is seen in 1% to 10% of patients with a penicillin allergy.[20]

Interactions

Like other β-lactam antibiotics, renal excretion of cefalexin is delayed by probenecid.[4] Alcohol consumption reduces the rate at which it is absorbed.[21] Cefalexin also interacts with metformin, an antidiabetic drug,[4] and this can lead to higher concentrations of metformin in the body.[4][22] Histamine H2 receptor antagonists like cimetidine and ranitidine may reduce the efficacy of cefalexin by delaying its absorption and altering its antimicrobial pharmacodynamics.[23]

Pharmacology

Mechanism of action

Cefalexin is a beta-lactam antibiotic of the cephalosporin family.[24] It is bactericidal and acts by inhibiting synthesis of the peptidoglycan layer of the bacterial cell wall.[25] As cefalexin closely resembles d-alanyl-d-alanine, an amino acid ending on the peptidoglycan layer of the cell wall, it is able to irreversibly bind to the active site of PBP, which is essential for the synthesis of the cell wall.[25] It is most active against gram-positive cocci, and has moderate activity against some gram-negative bacilli.[4] However, some bacterial cells have the enzyme β-lactamase, which hydrolyzes the beta-lactam ring, rendering the drug inactive. This contributes to antibacterial resistance towards cefalexin.[26]

Pharmacokinetics

Like most other cephalosporins, cefalexin is not metabolized or otherwise inactivated in the body.[23][27] The biological half-life of cefalexin is approximately 30 to 60 minutes.[27]

Society and culture

It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines, the safest and most effective medicines needed in a health system.[13] The World Health Organization classifies cefalexin as highly important for human medicine.[28]

Names

Cefalexin is the International Nonproprietary Name (INN) and Australian Approved Name (AAN), while cephalexin is the British Approved Name (BAN) and United States Adopted Name (USAN). Brand names for cefalexin include Keflex, Acfex, Cephalex, Ceporex, L-Xahl, Medoxine, Ospexin, and Torlasporin.[29]

Cost

Cefalexin is relatively inexpensive.[30] A seven-day course of cefalexin costs a consumer about CA$25 in Canada in 2014.[31] The wholesale cost of this amount is about CA$4.76 as of 2019.[32] In the United States this amount costs a consumer about US$20.96 as of 2019.[33] In Australia a course of treatment costs from A$12 to A$26.77 as of 2019.[34] In the United Kingdom the costs to the consumer is generally £9.[35] The wholesale price in the developing world is about US$2.18 as of 2015.[36]

References

- McPherson, Edwin M. (2007). Pharmaceutical Manufacturing Encyclopedia (3rd ed.). Burlington: Elsevier. p. 915. ISBN 9780815518563. Archived from the original on 2017-09-08.

- "Cephalexin Use During Pregnancy". Drugs.com. 28 December 2018. Retrieved 7 February 2020.

- McEvoy, G.K. (ed.). American Hospital Formulary Service — Drug Information 95. Bethesda, MD: American Society of Hospital Pharmacists, Inc., 1995 (Plus Supplements 1995)., p. 166

- "Cephalexin". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 2014-05-01. Retrieved Apr 21, 2014.

- Brunton, Laurence L. (2011). "53, Penicillins, Cephalosporins, and Other β-Lactam Antibiotics". Goodman & Gilman's pharmacological basis of therapeutics (12th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0071624428.

- "Prescribing medicines in pregnancy database". Australian Government. 3 March 2014. Archived from the original on 8 April 2014. Retrieved 22 April 2014.

- Wendy Jones (2013). Breastfeeding and Medication. Routledge. p. 227. ISBN 9781136178153. Archived from the original on 2017-09-08.

- Hey, Edmund, ed. (2007). Neonatal formulary 5 drug use in pregnancy and the first year of life (5th ed.). Blackwell. p. 67. ISBN 9780470750353. Archived from the original on 2017-09-08.>

- US patent 3275626, Robert B Morin & Billy G Jackson, "Penicillin conversion via sulfoxide", published 1966-09-27, issued 1966-09-27, assigned to Eli Lilly and Co

- US patent 3507861, Robert B Morin & Billy G Jackson, "Certain 3-methyl-cephalosporin compounds", published 1970-04-21, issued 1970-04-21, assigned to Eli Lilly and Co

- Ravina, Enrique (2011). The evolution of drug discovery : from traditional medicines to modern drugs (1. Aufl. ed.). Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. p. 267. ISBN 9783527326693. Archived from the original on 2017-09-08.

- Hanlon, Geoffrey; Hodges, Norman (2012). Essential Microbiology for Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Science. Hoboken: Wiley. p. 140. ISBN 9781118432433. Archived from the original on 2017-09-08.

- World Health Organization (2019). World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 21st list 2019. Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/325771. WHO/MVP/EMP/IAU/2019.06. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- "The Top 300 of 2020". ClinCalc. Retrieved 11 April 2020.

- "Cephalexin - Drug Usage Statistics". ClinCalc. Retrieved 11 April 2020.

- "Human Antimicrobial Drug Use Report 2012/2013" (PDF). Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC). November 2014. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 21, 2015. Retrieved February 24, 2015.

- Australia's Health 2012: The Thirteenth Biennial Health Report of the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. 2012. p. 408. ISBN 9781742493053. Archived from the original on 2017-09-08.

- "FDA Cephalexin drug label" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 18 April 2014. Retrieved 18 April 2014.

- "Cephalexin Side Effects". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 8 February 2015. Retrieved 9 February 2015.

- Haberfeld, H, ed. (2009). Austria-Codex (in German) (2009/2010 ed.). Vienna: Österreichischer Apothekerverlag. ISBN 3-85200-196-X.

- Barrio Lera JP, Alvarez AI, Prieto JG (Jun 1991). "Effects of ethanol on the pharmacokinetics of cephalexin and cefadroxil in the rat". Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences. 80 (6): 511–6. doi:10.1002/jps.2600800602. PMID 1941538.

- Jayasagar G, Krishna Kumar M, Chandrasekhar K, Madhusudan Rao C, Madhusudan Rao Y (2002). "Effect of cephalexin on the pharmacokinetics of metformin in healthy human volunteers". Drug Metabolism and Drug Interactions. 19 (1): 41–8. doi:10.1515/dmdi.2002.19.1.41. PMID 12222753.

- M. Lindsay Grayson (Editor in Chief) (2 October 2017). Kucers' The Use of Antibiotics: A Clinical Review of Antibacterial, Antifungal, Antiparasitic, and Antiviral Drugs, Seventh Edition - Three Volume Set. CRC Press. pp. 364–. ISBN 978-1-4987-4796-7.

- Bothara SS, Kadam KR, Mahadik KG (2006). "Antibiotics". Principles of Medicinal Chemistry. 1 (14th ed.). Pune: Nirali Prakashan. p. 81. ISBN 8185790043.

- Fisher JF, Meroueh SO, Mobashery S (Feb 2005). "Bacterial resistance to beta-lactam antibiotics: compelling opportunism, compelling opportunity". Chemical Reviews. 105 (2): 395–424. doi:10.1021/cr030102i. PMID 15700950.

- Drawz SM, Bonomo RA (Jan 2010). "Three decades of beta-lactamase inhibitors". Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 23 (1): 160–201. doi:10.1128/CMR.00037-09. PMC 2806661. PMID 20065329.

- Linda Skidmore-Roth (16 July 2015). Mosby's Drug Guide for Nursing Students, with 2016 Update. Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 181–. ISBN 978-0-323-17297-4.

- World Health Organization (2019). Critically important antimicrobials for human medicine (6th revision ed.). Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/312266. ISBN 9789241515528. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- "Cefalexin International". Drugs.com. 3 February 2020. Retrieved 8 February 2020.

- "Cephalexin Generic Keftab, Keflex, Keflet". GoodRx. Retrieved 30 March 2020.

- "Price Comparison of Commonly Prescribed Pharmaceuticals in Alberta 2014" (PDF). Retrieved 25 November 2019.

- "Online Formulary 2019". formulary.drugplan.health.gov.sk.ca. Retrieved 25 November 2019.

- "Cephalexin Prices, Coupons & Patient Assistance Programs". Drugs.com. Retrieved 25 November 2019.

- Health, Australian Government Department of. "Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS) |". Australian Government Department of Health. Retrieved 25 November 2019.

- "How much is the NHS prescription charge?". Retrieved 6 February 2020.

- "Search Results By Name". The International Medical Products Price Guide. Retrieved 25 November 2019.

External links

- "Cephalexin". Drug Information Portal. U.S. National Library of Medicine.