Cardiac tamponade

Cardiac tamponade, also known as pericardial tamponade, is when fluid in the pericardium (the sac around the heart) builds up, resulting in compression of the heart.[2] Onset may be rapid or gradual.[2] Symptoms typically include those of cardiogenic shock including shortness of breath, weakness, lightheadedness, and cough.[1] Other symptoms may relate to the underlying cause.[1]

| Cardiac tamponade | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Pericardial tamponade |

| |

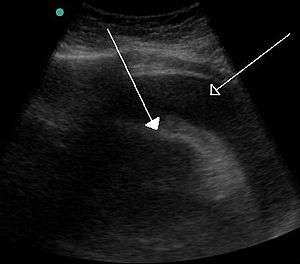

| A very large pericardial effusion resulting in tamponade as a result of bleeding from cancer as seen on ultrasound. Closed arrow - the heart; open arrow - the effusion | |

| Specialty | Cardiac surgery |

| Symptoms | Shortness of breath, weakness, lightheadedness, cough[1] |

| Usual onset | Rapid or more gradual[2] |

| Causes | Cancer, kidney failure, chest trauma, pericarditis, tuberculosis[2][1] |

| Diagnostic method | Symptoms and ultrasound of the heart[2] |

| Treatment | Drainage (pericardiocentesis, pericardial window, pericardiectomy)[2] |

| Frequency | 2 per 10,000 per year (US)[3] |

Common causes of cardiac tamponade include cancer, kidney failure, chest trauma, and pericarditis.[2] Other causes include connective tissues diseases, hypothyroidism, aortic rupture, and complications of cardiac surgery.[4] In Africa, tuberculosis is a relatively common cause.[1]

Diagnosis may be suspected based on low blood pressure, jugular venous distension, pericardial rub, or quiet heart sounds.[2][1] The diagnosis may be further supported by specific electrocardiogram (ECG) changes, chest X-ray, or an ultrasound of the heart.[2] If fluid increases slowly the pericardial sac can expand to contain more than 2 liters; however, if the increase is rapid as little as 200 mL can result in tamponade.[2]

When tamponade results in symptoms, drainage is necessary.[5] This can be done by pericardiocentesis, surgery to create a pericardial window, or a pericardiectomy.[2] Drainage may also be necessary to rule out infection or cancer.[5] Other treatments may include the use of dobutamine or in those with low blood volume, intravenous fluids.[1] Those with few symptoms and no worrisome features can often be closely followed.[2] The frequency of tamponade is unclear.[6] One estimate from the United States places it at 2 per 10,000 per year.[3]

Signs and symptoms

Onset may be rapid (acute) or more gradual (subacute).[7][2] Signs of cardiac tamponade typically include those of cardiogenic shock including shortness of breath, weakness, lightheadedness, and cough.[1] Other symptoms may relate to the underlying cause.[1]

Other general signs of shock (such as fast heart rate, shortness of breath and decreasing level of consciousness) may also occur. However, some of these signs may not be present in certain cases. A fast heart rate, although expected, may be absent in people with uremia and hypothyroidism.[1]

Causes

Cardiac tamponade is caused by a large or uncontrolled pericardial effusion, i.e. the buildup of fluid inside the pericardium.[8] This commonly occurs as a result of chest trauma (both blunt and penetrating),[9] but can also be caused by myocardial rupture, cancer, uremia, pericarditis, or cardiac surgery,[8] and rarely occurs during retrograde aortic dissection,[10] or while the person is taking anticoagulant therapy.[11] The effusion can occur rapidly (as in the case of trauma or myocardial rupture), or over a more gradual period of time (as in cancer). The fluid involved is often blood, but pus is also found in some circumstances.[8]

Causes of increased pericardial effusion include hypothyroidism, physical trauma (either penetrating trauma involving the pericardium or blunt chest trauma), pericarditis (inflammation of the pericardium), iatrogenic trauma (during an invasive procedure), and myocardial rupture.

Surgery

One of the most common settings for cardiac tamponade is in the first 24 to 48 hours after heart surgery. After heart surgery, chest tubes are placed to drain blood. These chest tubes, however, are prone to clot formation. When a chest tube becomes occluded or clogged, the blood that should be drained can accumulate around the heart, leading to tamponade.

Pathophysiology

The outer layer of the heart is made of fibrous tissue[12] which does not easily stretch, so once fluid begins to enter the pericardial space, pressure starts to increase.[8]

If fluid continues to accumulate, each successive diastolic period leads to less blood entering the ventricles. Eventually, increasing pressure on the heart forces the septum to bend in towards the left ventricle, leading to a decrease in stroke volume.[8] This causes the development of obstructive shock, which if left untreated may lead to cardiac arrest (often presenting as pulseless electrical activity).

Diagnosis

The three classic signs, known as Beck's triad, are low blood pressure, jugular-venous distension, and muffled heart sounds.[14] Other signs may include pulsus paradoxus (a drop of at least 10 mmHg in arterial blood pressure with inspiration),[8] and ST segment changes on the electrocardiogram,[14] which may also show low voltage QRS complexes,[11]

Medical imaging

Tamponade can often be diagnosed radiographically. Echocardiography, which is the diagnostic test of choice, often demonstrates an enlarged pericardium or collapsed ventricles. A large cardiac tamponade will show as an enlarged globular-shaped heart on chest x-ray. During inspiration, the negative pressure in the thoracic cavity will cause increased pressure into the right ventricle. This increased pressure in the right ventricle will cause the interventricular septum to bulge towards the left ventricle, leading to decreased filling of the left ventricle. At the same time, right ventricle volume is markedly diminished and sometimes it can collapse.[11]

Differential diagnosis

Initial diagnosis of cardiac tamponade can be challenging, as there is a broad differential diagnosis.[7] The differential includes possible diagnoses based on symptoms, time course, mechanism of injury, patient history. Rapid onset cardiac tamponade may also appear similary to pleural effusions, shock, pulmonary embolism, and tension pneumothorax.[9][7]

If symptoms appeared more gradually, the differential diagnosis includes acute heart failure.[15]

In a person with trauma presenting with pulseless electrical activity in the absence of hypovolemia and tension pneumothorax, the most likely diagnosis is cardiac tamponade.[16]

In addition to the diagnostic complications afforded by the wide-ranging differential diagnosis for chest pain, diagnosis can be additionally complicated by the fact that people will often be weak or faint at presentation. For instance, a fast rate of breathing and difficulty breathing on exertion that progresses to air hunger at rest can be a key diagnostic symptom, but it may not be possible to obtain such information from people who are unconscious or who have convulsions at presentation.[1]

Treatment

Pre-hospital care

Initial treatment given will usually be supportive in nature, for example administration of oxygen, and monitoring. There is little care that can be provided pre-hospital other than general treatment for shock. Some teams have performed an emergency thoracotomy to release clotting in the pericardium caused by a penetrating chest injury.

Prompt diagnosis and treatment is the key to survival with tamponade. Some pre-hospital providers will have facilities to provide pericardiocentesis, which can be life-saving. If the person has already suffered a cardiac arrest, pericardiocentesis alone cannot ensure survival, and so rapid evacuation to a hospital is usually the more appropriate course of action.

Hospital management

Initial management in hospital is by pericardiocentesis.[9] This involves the insertion of a needle through the skin and into the pericardium and aspirating fluid under ultrasound guidance preferably. This can be done laterally through the intercostal spaces, usually the fifth, or as a subxiphoid approach.[17][18] A left parasternal approach begins 3 to 5 cm left of the sternum to avoid the left internal mammary artery, in the 5th intercostal space.[19] Often, a cannula is left in place during resuscitation following initial drainage so that the procedure can be performed again if the need arises. If facilities are available, an emergency pericardial window may be performed instead,[9] during which the pericardium is cut open to allow fluid to drain. Following stabilization of the person, surgery is provided to seal the source of the bleed and mend the pericardium.

In people following heart surgery the nurses monitor the amount of chest tube drainage. If the drainage volume drops off, and the blood pressure goes down, this can suggest tamponade due to chest tube clogging. In that case, the person is taken back to the operating room for an emergency reoperation.

If aggressive treatment is offered immediately and no complications arise (shock, AMI or arrhythmia, heart failure, aneurysm, carditis, embolism, or rupture), or they are dealt with quickly and fully contained, then adequate survival is still a distinct possibility.

Epidemiology

The frequency of tamponade is unclear.[6] One estimate from the United States places it at 2 per 10,000 per year.[3] It is estimated to occur in 2% of those with stab or gunshot wounds to the chest.[20]

References

- Spodick, DH (Aug 14, 2003). "Acute cardiac tamponade". The New England Journal of Medicine. 349 (7): 684–90. doi:10.1056/NEJMra022643. PMID 12917306.

- Richardson, L (November 2014). "Cardiac tamponade". Journal of the American Academy of Physician Assistants. 27 (11): 50–1. doi:10.1097/01.jaa.0000455653.42543.8a. PMID 25343435.

- Kahan, Scott (2008). In a Page: Medicine. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 20. ISBN 9780781770354. Archived from the original on 2016-10-02.

- Schiavone, WA (February 2013). "Cardiac tamponade: 12 pearls in diagnosis and management". Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine. 80 (2): 109–16. doi:10.3949/ccjm.80a.12052. PMID 23376916.

- Sagristà-Sauleda, J; Mercé, AS; Soler-Soler, J (26 May 2011). "Diagnosis and management of pericardial effusion". World Journal of Cardiology. 3 (5): 135–43. doi:10.4330/wjc.v3.i5.135. PMC 3110902. PMID 21666814.

- Bodson, L; Bouferrache, K; Vieillard-Baron, A (October 2011). "Cardiac tamponade". Current Opinion in Critical Care. 17 (5): 416–24. doi:10.1097/mcc.0b013e3283491f27. PMID 21716107.

- Stashko, Eric; Meer, Jehangir M. (2019), "Cardiac Tamponade", StatPearls, StatPearls Publishing, PMID 28613742, retrieved 2019-08-02

- Porth, Carol; Carol Mattson Porth (2005). Pathophysiology: concepts of altered health states (7th ed.). Hagerstwon, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 978-0-7817-4988-6.

- Gwinnutt CL, Driscoll PA (2003). Trauma Resuscitation: The Team Approach (2nd ed.). Oxford: BIOS. ISBN 978-1-85996-009-7.

- Isselbacher EM, Cigarroa JE, Eagle KA (Nov 1994). "Cardiac tamponade complicating proximal (retrograde) aortic dissection. Is pericardiocentesis harmful?". Circulation. 90 (5): 2375–8. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.90.5.2375. PMID 7955196.

- Longmore, J. M.; Murray Longmore; Wilkinson, Ian; Supraj R. Rajagopalan (2004). Oxford handbook of clinical medicine (6th ed.). Oxford [Oxfordshire]: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-852558-5.

- Patton KT, Thibodeau GA (2003). Anatomy & physiology (5th ed.). St. Louis: Mosby. ISBN 978-0-323-01628-5.

- Smith, Ben (27 February 2017). "UOTW #78 - Ultrasound of the Week". Ultrasound of the Week. Archived from the original on 13 March 2017. Retrieved 13 March 2017.

- Holt L, Dolan B (2000). Accident and emergency: theory into practice. London: Baillière Tindall. ISBN 978-0-7020-2239-5.

- Chahine, Johnny; Alvey, Heidi (2019), "Left Ventricular Failure", StatPearls, StatPearls Publishing, PMID 30725783, retrieved 2019-08-02

- American College of Surgeons Committee on Trauma (2007). Advanced Trauma Life Support for Doctors, 7th Edition. Chicago: American College of Surgeons

- Shlamovitz, Gil (4 August 2011). "Pericardiocentesis". Medscape. Archived from the original on 23 August 2011. Retrieved 16 August 2011.

- Yarlagadda, Chakri (11 August 2011). "Cardiac Tamponade Treatment & Management". Medscape. Archived from the original on 16 August 2011. Retrieved 16 August 2011.

- Synovitz C.K., Brown E.J. (2011). Chapter 37. Pericardiocentesis. In Tintinalli J.E., Stapczynski J, Ma O, Cline D.M., Cydulka R.K., Meckler G.D., T (Eds), Tintinalli's Emergency Medicine: A Comprehensive Study Guide, 7e. Retrieved September 19, 2014 from "Chapter 37. Pericardiocentesis". Archived copy. The McGraw-Hill Companies. 2011. Archived from the original on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2014-09-20.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link).

- Marx, John; Walls, Ron; Hockberger, Robert (2013). Rosen's Emergency Medicine - Concepts and Clinical Practice. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 448. ISBN 978-1455749874. Archived from the original on 2016-10-02.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |

|