Canine distemper

Canine distemper (sometimes termed hardpad disease) is a viral disease that affects a wide variety of animal families, including domestic and wild species of dogs, coyotes, foxes, pandas, wolves, ferrets, skunks, raccoons, and large cats, as well as pinnipeds, some primates, and a variety of other species. Animals in the family Felidae, including many species of large cat as well as domestic cats, were long believed to be resistant to canine distemper, until some researchers reported the prevalence of CDV infection in large felids.[2] Both large Felidae and domestic cats are now known to be capable of infection, usually through close housing with dogs[2][3] or possibly blood transfusion from infected cats,[2] but such infections appear to be self-limiting and largely without symptoms.[3]

| Canine morbillivirus | |

|---|---|

.jpg) | |

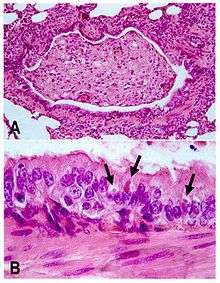

| Canine distemper virus cytoplasmic inclusion body (blood smear, Wright's stain) | |

| Virus classification | |

| (unranked): | Virus |

| Realm: | Riboviria |

| Phylum: | Negarnaviricota |

| Class: | Monjiviricetes |

| Order: | Mononegavirales |

| Family: | Paramyxoviridae |

| Genus: | Morbillivirus |

| Species: | Canine morbillivirus |

| Synonyms[1] | |

|

Canine distemper virus | |

In canines, distemper affects several body systems, including the gastrointestinal and respiratory tracts and the spinal cord and brain, with common symptoms that include high fever, eye inflammation and eye/nose discharge, labored breathing and coughing, vomiting and diarrhea, loss of appetite and lethargy, and hardening of nose and footpads. The viral infection can be accompanied by secondary bacterial infections and can present eventual serious neurological symptoms.

Canine distemper is caused by a single-stranded RNA virus of the family Paramyxoviridae (the same family of the viruses that causes measles, mumps, and bronchiolitis in humans). The disease is highly contagious via inhalation.[4] Morbidity and mortality may vary greatly among animal species, with up to 100% mortality in unvaccinated populations of ferrets. In domestic dogs, while the acute generalized form of distemper has a high mortality rate, disease duration and severity depends mainly on the animal's age and immune status and virulence of the infecting strain of the virus.[4][5] Despite extensive vaccination in many regions, it remains a major disease of dogs, and was the leading cause of infectious disease death in dogs, prior to a vaccine becoming available.[6]

The origin of the word "distemper" is from the Middle English distemperen, meaning to upset the balance of the humors, which is from the Old French destemprer, meaning to disturb, which is from the Vulgar Latin distemperare: Latin dis- and Latin temperare, meaning to not mix properly.[7][8]

Clinical signs

In dogs, signs of distemper vary widely from no signs, to mild respiratory signs indistinguishable from kennel cough, to severe pneumonia with vomiting, bloody diarrhea, and death.[9]

Commonly observed signs are a runny nose, vomiting and diarrhea, dehydration, excessive salivation, coughing and/or labored breathing, loss of appetite, and weight loss. If neurological signs develop, incontinence may ensue.[10][11] Central nervous system signs include a localized involuntary twitching of muscles or groups of muscles, seizures with salivation and jaw movements commonly described as "chewing-gum fits", or more appropriately as "distemper myoclonus". As the condition progresses, the seizures worsen and advance to grand mal convulsions followed by death of the animal. The animal may also show signs of sensitivity to light, incoordination, circling, increased sensitivity to sensory stimuli such as pain or touch, and deterioration of motor capabilities. Less commonly, they may lead to blindness and paralysis. The length of the systemic disease may be as short as 10 days, or the start of neurological signs may not occur until several weeks or months later. Those few that survive usually have a small tic or twitch of varying levels of severity. With time, this tic usually diminishes somewhat in its severity.[12][10]

Lasting signs

A dog that survives distemper continues to have both nonlife-threatening and life-threatening signs throughout its lifespan. The most prevalent nonlife-threatening symptom is hard pad disease. This occurs when a dog experiences the thickening of the skin on the pads of its paws, as well as on the end of its nose. Another lasting symptom that is common is enamel hypoplasia. Puppies, especially, have damage to the enamel of teeth that are not completely formed or those that have not yet grown through the gums. This is a result of the virus killing the cells responsible for manufacturing the tooth enamel. These affected teeth tend to erode quickly.[13]

Life-threatening signs usually include those due to the degeneration of the nervous system. Dogs that have been infected with distemper tend to suffer a progressive deterioration of mental abilities and motor skills. With time, the dog can develop more severe seizures, paralysis, reduction in sight, and incoordination. These dogs are usually humanely euthanized because of the immense pain and suffering they face.[13]

Virology

Distemper is caused by a single-stranded RNA virus of the family Paramyxoviridae, which is a close relative of the viruses that cause measles in humans and rinderpest in animals.[12][14]

Genetic diversity

Geographically distinct lineages of the canine distemper virus are genetically diverse. This diversity arises from mutation, and when two genetically distinct viruses infect the same cell, from homologous recombination[15]

Host range

Distemper, or hardpad disease in canines,[16] affects animals in the families Canidae (dog, fox, wolf, raccoon dog), Mustelidae (ferret, mink, skunk, wolverine, marten, badger, otter),[12][16] Procyonidae (raccoon, coati), Ailuridae (red panda), Ursidae (bear), Elephantidae (Asian elephant), and some primates (e.g., Japanese monkey),[12] as well as Viverridae (raccoon-like South Asian binturong, palm civet),[12] Hyaenidae (hyena), Pinnipedia (seals, walrus, sea lion, etc.),[17][10] and large Felidae (cats,[12] though not domestic cats.)

In a captive population of giant pandas in China (Shanxi Rare Wild Animal Rescue and Research Center), six of 22 captive pandas were infected by CDV. All but one infected panda died; the survivor had previously been vaccinated.[18]

Mechanism

Canine distemper virus affects nearly all body systems.[19] Puppies from 3-6 months old are particularly susceptible.[20] CDV spreads through aerosol droplets and through contact with infected bodily fluids, including nasal and ocular secretions, feces, and urine, 6 to 22 days after exposure. It can also be spread by food and water contaminated with these fluids.[21][22] The time between infection and disease is 14 to 18 days, although a fever can appear from 3 to 6 days after infection.[23]

Canine distemper virus tends to orient its infection towards the lymphoid, epithelial, and nervous tissues. The virus initially replicates in the lymphatic tissue of the respiratory tract. The virus then enters the blood stream and infects the respiratory, gastrointestinal, urogenital, epithelial, and central nervous systems, and optic nerves.[12] Therefore, the typical pathologic features of canine distemper include lymphoid depletion (causing immunosuppression and leading to secondary infections), interstitial pneumonia, encephalitis with demyelination, and hyperkeratosis of the nose and foot pads.

The virus first appears in bronchial lymph nodes and tonsils 2 days after exposure. The virus then enters the bloodstream on the second or third day.[22] A first round of acute fever tends to begin around 3-8 days after infection, which is often accompanied by a low white blood cell count, especially of lymphocytes, as well as low platelet count. These signs may or may not be accompanied by anorexia, a runny nose, and discharge from the eye. This first round of fever typically recedes rapidly within 96 hours, and then a second round of fever begins around the 11th or 12th day and lasts at least a week. Gastrointestinal and respiratory problems tend to follow, which may become complicated with secondary bacterial infections. Inflammation of the brain and spinal cord, otherwise known as encephalomyelitis, either is associated with this, subsequently follows, or comes completely independent of these problems. A thickening of the footpads sometimes develops, and vesicular pustular lesions on the abdomen usually develop. Neurological signs typically are found in the animals with thickened footpads from the virus.[12][10] About half of sufferers experience meningoencephalitis.[10] Less than 50% of the adult dogs that contract the disease die from it. Among puppies, the death rate often reaches 80%.[24]

Diagnosis

The above signs, especially fever, respiratory signs, neurological signs, and thickened footpads, occurring in unvaccinated dogs strongly indicate canine distemper. However, several febrile diseases match many of the signs of the disease and only recently has distinguishing between canine hepatitis, herpes virus, parainfluenza, and leptospirosis been possible.[10] Thus, finding the virus by various methods in the dog's conjunctival cells or foot pads gives a definitive diagnosis. In older dogs that develop distemper encephalomyelitis, diagnosis may be more difficult, since many of these dogs have an adequate vaccination history.[25]

An additional test to confirm distemper is a brush border slide of the bladder transitional epithelium of the inside lining from the bladder, stained with Diff-Quik. These infected cells have inclusions which stain a carmine red color, found in the paranuclear cytoplasm readability. About 90% of the bladder cells will be positive for inclusions in the early stages of distemper.[26]

Prevention

A number of vaccines against canine distemper exist for dogs (ATCvet code: QI07AD05 (WHO) and combinations) and domestic ferrets (QI20DD01 (WHO)), which in many jurisdictions are mandatory for pets. Infected animals should be quarantined from other dogs for several months owing to the length of time the animal may shed the virus.[12] The virus is destroyed in the environment by routine cleaning with disinfectants, detergents, or drying. It does not survive in the environment for more than a few hours at room temperature (20–25 °C), but can survive for a few weeks in shady environments at temperatures slightly above freezing.[27] It, along with other labile viruses, can also persist longer in serum and tissue debris.[22]

Despite extensive vaccination in many regions, it remains a major disease of dogs.[28]

To prevent canine distemper, puppies should begin vaccination at 6-8 weeks of age and then continue getting the “booster shot” every 2-4 weeks until they are 16 weeks of age. Without the full series of shots, the vaccination does not provide protection against the virus. Since puppies are typically sold at the age of 8-10 weeks, they typically receive the first shot while still with their breeder, but the new owner often does not finish the series. These dogs are not protected against the virus, so are susceptible to canine distemper infection, continuing the downward spiral that leads to outbreaks throughout the world.[29]

Treatment

No specific treatment for the canine distemper is known. As with measles, the treatment is symptomatic and supportive.[12] Care is geared towards treating fluid/electrolyte imbalances, neurological symptoms, and preventing any secondary bacterial infections. Examples include administering fluids, electrolyte solutions, analgesics, anticonvulsants, broad-spectrum antibiotics, antipyretics, parenteral nutrition, and nursing care.[30]

Outcome

The mortality rate of the virus largely depends on the immune status of the infected dogs. Puppies experience the highest mortality rate, where complications such as pneumonia and encephalitis are more common.[22] In older dogs that develop distemper, encephalomyelitis and vestibular disease may be present.[25] Around 15% of canine inflammatory central nervous system diseases are a result of CDV.[31]

Epidemiology

The prevalence of canine distemper in the community has decreased dramatically due to the availability of vaccinations. However, the disease continues to spread among unvaccinated populations, such as those in animal shelters and pet stores. This provides a great threat to both the rural and urban communities throughout the United States, affecting both shelter and domestic canines. Despite the effectiveness of the vaccination, outbreaks of this disease continue to occur nationally. In April 2011, the Arizona Humane Society released a valley-wide pet health alert throughout Phoenix, Arizona.[32]

Outbreaks of canine distemper continue to occur throughout the United States and elsewhere and are caused by many factors, including proximity to wild animals and lack of vaccinated animals. This problem is even greater within areas such as Arizona, owing to the vast amount of rural land. An unaccountable number of strays that lack vaccinations reside in these areas, so they are more susceptible to diseases such as canine distemper. These strays act as a reservoir for the virus, spreading it throughout the surrounding area, including urban areas. Puppies and dogs that have not received their shots can then be infected in a place where many dogs interact, such as a dog park.

History

In Europe, the first report of canine distemper occurred in Spain in 1761.[33] Edward Jenner described the disease in 1809,[33] but French veterinarian Henri Carré determined that the disease was caused by a virus in 1905.[33] Carré's findings were disputed by researchers in England until 1926, when Patrick Laidlaw and G.W. Dunkin confirmed that the disease was, in fact, caused by a virus.[33]

The first vaccine against canine distemper was developed by an Italian named Puntoni.[34] In 1923 and 1924, Puntoni published two articles in which he added formalin to brain tissue from infected dogs to create a vaccine which successfully prevented the disease in healthy dogs.[34] A commercial vaccine was developed in 1950, yet owing to limited use, the virus remains prevalent in many populations.[35]

The domestic dog has largely been responsible for introducing canine distemper to previously unexposed wildlife, and now causes a serious conservation threat to many species of carnivores and some species of marsupials. The virus contributed to the near-extinction of the black-footed ferret. It also may have played a considerable role in the extinction of the thylacine (Tasmanian tiger) and recurrently causes mortality among African wild dogs.[14] In 1991, the lion population in Serengeti, Tanzania, experienced a 20% decline as a result of the disease.[36] The disease has also mutated to form phocid distemper virus, which affects seals.[10]

References

- "ICTV Taxonomy history: Canine morbillivirus". International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV). Retrieved 15 January 2019.

- Ikeda, Yasuhiro; Nakamura, Kazuya; Miyazawa, Takayuki; Chen, Ming-Chu; Kuo, Tzong-Fu; Lin, James A; Mikami, Takeshi; Kai, Chieko; Takahashi, Eiji (May 2001). "Seroprevalence of Canine Distemper Virus in Cats". Clin Vaccine Immunol. 8 (3): 641–644. doi:10.1128/CDLI.8.3.641-644.2001. PMC 96116. PMID 11329473.

- Greene, Craig E; Appel, Max J (2006). "3. Canine distemper". In Greene, Craig E (ed.). Infectious Diseases of the Dog and Cat (3rd ed.). St Louis, MO: Elsevier. ISBN 978-1-4160-3600-5.

- Deem, Sharon L.; Spelman, Lucy H.; Yates, Rebecca A.; Montali, Richard J. (December 2000). "Canine Distemper in Terrestrial Carnivores: A Review" (PDF). Journal of Zoo and Wildlife Medicine. 31 (4): 441–451. doi:10.1638/1042-7260(2000)031[0441:CDITCA]2.0.CO;2. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2017-05-17. Retrieved 2017-12-05.

- Andreas, Beineke; Baumgärtner, Wolfgang; Wohlsein, Peter (13 September 2015). "Cross-species transmission of canine distemper virus—an update". One Health. 1: 49–59. doi:10.1016/j.onehlt.2015.09.002. PMC 5462633. PMID 28616465.

- "Animal Health" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-11-07. Retrieved 2017-10-30.

- "distemper (definition)". Oxford Living Dictionaries - English. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on 2017-12-06. Retrieved 2017-12-06.

- "distemper (definition)". American Heritage Dictionary. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Archived from the original on 2018-05-09. Retrieved 2017-12-06.

- Greene, CE; Vandevelde, M (2012). "Chapter 3: Canine distemper". In Greene, Craig E. (ed.). Infectious diseases of the dog and cat (4th ed.). St. Louis, Mo.: Elsevier/Saunders. pp. 25–42. ISBN 978-1-4160-6130-4.

- Jones, T.C.; Hunt, R.D.; King, N.W. (1997). Veterinary Pathology. Blackwell Publishing.

- Hirsh DC, Zee YC (1999). Veterinary Microbiology. Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 978-0-86542-543-9.

- Kate E. Creevy, 2013, Overview of Canine Distemper, in The Merck Veterinary Manual (online): Veterinary Professionals: Generalized Conditions: Canine Distemper, see "Canine Distemper Overview - Generalized Conditions". Archived from the original on 2014-12-23. Retrieved 2014-12-15., accessed 15 December 2014.

- "Canine Distemper: What You Need To Know". Veterinary Insider. 2010-12-06. Archived from the original on 2012-05-02. Retrieved 2012-04-09.

- McCarthy AJ, Shaw MA, Goodman SJ (December 2007). "Pathogen evolution and disease emergence in carnivores". Proc. Biol. Sci. 274 (1629): 3165–74. doi:10.1098/rspb.2007.0884. PMC 2293938. PMID 17956850.

- Yuan C, Liu W, Wang Y, Hou J, Zhang L, Wang G. Homologous recombination is a force in the evolution of canine distemper virus. PLoS One. 2017 Apr 10;12(4):e0175416. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0175416. ECollection 2017. PMID: 28394936

- Otto M. Radostits, David A. Ashford, Craig E. Greene, Ian Tizard, et al., 2011, Canine Distemper (Hardpad Disease), in The Merck Manual for Pet Health (online): Pet Owners: Dog Disorders and Diseases: Disorders Affecting Multiple Body Systems of Dogs, see "Canine Distemper (Hardpad Disease) - Dog Owners". Archived from the original on 2014-12-16. Retrieved 2014-12-15., accessed 15 December 2014.

- Kennedy, Seamus, et al. "Mass die-off of Caspian seals caused by canine distemper virus." Emerging infectious diseases 6.6 (2000): 637.

- Feng, Na; Yu, Yicong; Wang, Tiecheng; Wilker, Peter; Wang, Jianzhong; Li, Yuanguo; Sun, Zhe; Gao, Yuwei; Xia, Xianzhu (16 June 2016). "Fatal canine distemper virus infection of giant pandas in China". Scientific Reports. 6 (1): 27518. Bibcode:2016NatSR...627518F. doi:10.1038/srep27518. PMC 4910525. PMID 27310722.

- Beineke, A; Baumgärtner, W; Wohlsein, P (December 2015). "Cross-species transmission of canine distemper virus-an update". One Health. 1: 49–59. doi:10.1016/j.onehlt.2015.09.002. PMC 5462633. PMID 28616465.

- "Health Topics: Pet Health: Canine Distemper: Canine Distemper Overview". HealthCommunities.com. 4 Nov 2014 [28 Feb 2001]. Archived from the original on 2014-12-20. Retrieved 2014-12-15., accessed 15 December 2014.

- Carter, G.R.; Flores, E.F.; Wise, D.J. (2006). "Paramyxoviridae". A Concise Review of Veterinary Virology. Retrieved 2006-06-24.

- Hirsch, D.C.; Zee, C.; et al. (1999). Veterinary Microbiology. Blackwell Publishing.

- Appel, M.J.G.; Summers, B.A. (1999). "Canine Distemper: Current Status". Recent Advances in Canine Infectious Diseases. Archived from the original on 2005-09-01. Retrieved 2006-06-24.

- "Canine Distemper". American Canine Association, Inc. Archived from the original on 2015-02-02. Retrieved 2015-04-13.

- Dewey, C.W. (2003). A Practical Guide to Canine and Feline Neurology. Iowa State Pr.

- "NDV-Induced Serum". Kind Hearts in Action. November 5, 2009. Archived from the original on June 25, 2012. Retrieved October 31, 2012.

- "Canine Distemper (CDV)". UC Davis Koret Shelter Medicine Program. 2004. Archived from the original on 2015-10-10. Retrieved 2013-08-17.

- EST 2011, Sun Nov 27 19:17:12. "Canine Distemper". Vetstreet. Retrieved 2019-12-12.

- "Canine Distemper: Prevention of Infections". MarvistaVet. Archived from the original on 2012-04-21. Retrieved 2012-04-09.

- "Overview of Canine Distemper: Canine Distemper: Merck Veterinary Manual". www.merckvetmanual.com. Kenilworth, N.J., U.S.: Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp. 2009. Archived from the original on 2016-10-05. Retrieved 2016-02-13.

- Elia G, Belloli C, Cirone F, et al. (February 2008). "In vitro efficacy of ribavirin against canine distemper virus". Antiviral Res. 77 (2): 108–13. doi:10.1016/j.antiviral.2007.09.004. PMID 17949825.

- "AHS ISSUES VALLEYWIDE PET HEALTH ALERT". Arizona Humane Society. Archived from the original on 2012-04-15. Retrieved 2012-04-09.

- Appel, MJG; Gillespie, JH (1972). "Canine Distemper Virus". Volume 11 of the series Virology Monographs / Die Virusforschung in Einzeldarstellungen. Vienna: Springer Vienna. pp. 1–96. ISBN 978-3-7091-8302-1.

- Tizard, I (1999). "Grease, anthraxgate, and kennel cough: a revisionist history of early veterinary vaccines". Advances in Veterinary Medicine. 41: 7–24. doi:10.1016/S0065-3519(99)80005-6. ISBN 9780120392421. PMID 9890006.

- Pomeroy, Laura W.; Bjørnstad, Ottar N; Holmes, Edward C. (2008). "The Evolutionary and Epidemiological Dynamics of the Paramyxoviridae". Journal of Molecular Evolution. 66 (2): 98–106. Bibcode:2008JMolE..66...98P. doi:10.1007/s00239-007-9040-x. PMC 3334863. PMID 18217182.

- Assessment, M.E. (2005). Ecosystems and human well-being. World Resources Institute.

Further reading

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Canine distemper. |

- Di Sabatino, D; Lorusso, A; Di Francesco, CE; Gentile, L; Di Pirro, V; Bellacicco, AL; Giovannini, A; Di Francesco, G; Marruchella, G; Marsilio, F; Savini, G (Jan 2014). "Arctic lineage-canine distemper virus as a cause of death in Apennine wolves (Canis lupus) in Italy". PLOS ONE. 9 (1): e82356. Bibcode:2014PLoSO...982356D. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0082356. PMC 3896332. PMID 24465373.