Bushranger

Bushrangers were originally escaped convicts in the early years of the British settlement of Australia who used the Australian bush as a refuge to hide from the authorities. By the 1820s, the term "bushranger" had evolved to refer to those who took up "robbery under arms" as a way of life, using the bush as their base.

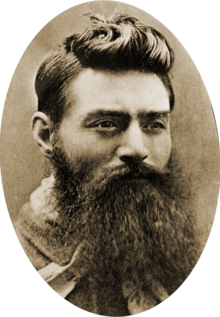

Bushranging thrived during the gold rush years of the 1850s and 1860s when the likes of Ben Hall, Frank Gardiner and John Gilbert led notorious gangs in the country districts of New South Wales. These "Wild Colonial Boys", mostly Australian-born sons of convicts, were roughly analogous to British "highwaymen" and outlaws of the American Old West, and their crimes typically included robbing small-town banks and coach services. In other infamous cases, such as that of Dan Morgan, the Clarke brothers, and Australia's best-known bushranger, Ned Kelly, numerous policemen were murdered. The number of bushrangers declined due to better policing and improvements in rail transport and communication technology, such as telegraphy. Although bushrangers appeared sporadically into the early 20th century, most historians regard Kelly's capture and execution in 1880 as effectively representing the end of the bushranging era.

Bushranging exerted a powerful influence in Australia, lasting for almost a century and predominating in the eastern colonies, with several notable bushrangers operating elsewhere on the continent. Its origins in a convict system bred a unique kind of desperado, most frequently with an Irish political background. Native-born bushrangers also expressed nascent Australian nationalist views and are recognised as "the first distinctively Australian characters to gain general recognition."[2] As such, a number of bushrangers became folk heroes and symbols of rebellion against the authorities, admired for their bravery, rough chivalry and colourful personalities. However, in stark contrast to romantic portrayals in the arts and popular culture, bushrangers tended to lead lives that were "nasty, brutish and short", while some were notorious for their cruelty and bloodthirst. Australian attitudes toward bushrangers remain complex and ambivalent.

Etymology

The earliest documented use of the term appears in a February 1805 issue of The Sydney Gazette, which reports that a cart had been stopped between Sydney and Hawkesbury by three men "whose appearance sanctioned the suspicion of their being bush-rangers".[3] John Bigge described bushranging in 1821 as "absconding in the woods and living upon plunder and the robbery of orchards." Charles Darwin likewise recorded in 1835 that a bushranger was "an open villain who subsists by highway robbery, and will sooner be killed than taken alive".[4]

History

Over 2,000 bushrangers are estimated to have roamed the Australian countryside, beginning with the convict bolters and drawing to a close after Ned Kelly's last stand at Glenrowan.[5]

Convict era (1780s–1840s)

Bushranging began soon after British settlement with the establishment of New South Wales as a penal colony in 1788. The majority of early bushrangers were convicts who had escaped prison, or from the properties of landowners to whom they had been assigned as servants. These bushrangers, also known as "bolters", preferred the hazards of wild, unexplored bushland surrounding Sydney to the deprivation and brutality of convict life. The first notable bushranger, African convict John Caesar, robbed settlers for food, and had a brief, tempestuous alliance with Aboriginal resistance fighters during Pemulwuy's War. While other bushrangers would go on to fight alongside Indigenous Australians in frontier conflicts with the colonial authorities, the Government tried to bring an end to any such collaboration by rewarding Aborigines for returning convicts to custody. Aboriginal trackers would play a significant role in the hunt for bushrangers.

Colonel Godfrey Mundy described convict bushrangers as "desperate, hopeless, fearless; rendered so, perhaps, by the tyranny of a gaoler, of an overseer, or of a master to whom he has been assigned." Edward Smith Hall, editor of early Sydney newspaper The Monitor, agreed that the convict system was a breeding-ground for bushrangers due to its savagery, with starvation and acts of torture being rampant. "Liberty or Death!" was the cry of convict bushrangers, and in large numbers they roamed beyond Sydney, some hoping to reach China, which was commonly believed to be connected by an overland route. Some bolters seized boats and set sail for foreign lands, but most were hunted down and brought back to Australia. Others attempted to inspire an overhaul of the convict system, or simply sought revenge on their captors. This latter desire found expression in the convict ballad "Jim Jones at Botany Bay", in which Jones, the narrator, plans to join bushranger Jack Donahue and "gun the floggers down".

Donahue was the most notorious of the early New South Wales bushrangers, terrorising settlements outside Sydney from 1827 until he was fatally shot by a trooper in 1830.[3] That same year, west of the Blue Mountains, convict Ralph Entwistle sparked a bushranging insurgency known as the Bathurst Rebellion. He and his gang raided farms, liberating assigned convicts by force in the process, and within a month, his personal army numbered 130 bushrangers. Following gun battles with vigilante posses, mounted policemen and soldiers of the 39th and 57th Regiment of Foot, he and nine of his men were captured and executed.

Convict bushrangers were particularly prevalent in the penal colony of Van Diemen's Land (now the state of Tasmania), established in 1803.[3] The island's most powerful bushranger, the self-styled "Lieutenant Governor of the Woods", Michael Howe, led a gang of up to one hundred members "in what amounted to a civil war" with the colonial government.[6] His control over large swathes of the island prompted elite squatters from Hobart and Launceston to collude with him, and for six months in 1815, Lieutenant-Governor Thomas Davey, fearing a convict uprising, declared martial law in an effort to suppress Howe's influence. Most of the gang had either been captured or killed by 1818, the year soldiers shot Howe dead.[6] Vandemonian bushranging peaked in the 1820s with hundreds of bolters at large, among the most notorious being Matthew Brady's gang, and cannibal serial killers Alexander Pearce and Thomas Jeffries. Originally a New South Wales bushranger, Jackey Jackey (alias of William Westwood) was sent to Van Diemen's Land in 1842 after attempting to escape Cockatoo Island. In 1843, he escaped Port Arthur, and took up bushranging in Tasmania's mountains, but was recaptured and sent to Norfolk Island, where, as leader of the 1846 Cooking Pot Uprising, he murdered three constables, and was hanged along with sixteen of his men.

The era of convict bushrangers gradually faded with the decline in penal transportations to Australia in the 1840s. It had ceased by the 1850s to all colonies except Western Australia, which accepted convicts between 1850 and 1868. The best-known convict bushranger of the colony was the prolific escapee Moondyne Joe.

Gold rush era (1850s–1860s)

The bushrangers' heyday was the Gold Rush years of the 1850s and 1860s as the discovery of gold gave bushrangers access to great wealth that was portable and easily converted to cash. Their task was assisted by the isolated location of the goldfields and a police force decimated by troopers abandoning their duties to join the gold rush.[5]

George Melville was hanged in front of a large crowd for robbing the McIvor gold escort near Castlemaine in 1853.[5]

Bushranging numbers flourished in New South Wales with the rise of the colonial-born sons of poor, often ex-convict squatters who were drawn to a more glamorous life than mining or farming.[5]

Much of the activity in this era was in the Lachlan Valley, around Forbes, Yass and Cowra.[5]

Frank Gardiner, John Gilbert and Ben Hall led the most notorious gangs of the period. Other active bushrangers included Dan Morgan, based in the Murray River.[5]

Captain Thunderbolt (alias of Frederick Ward) robbed inns and mail-coaches across northern New South Wales for six and a half years, one of the longest careers of any bushranger.[3] He sometimes operated alone; at other times, he led gangs, and was accompanied by his Aboriginal 'wife', Mary Ann Bugg, who is credited with helping extend his career.[3] Ward was fatally shot by a policeman in 1870, and with his death, the New South Wales bushranging epidemic that began in the 1860s came to an end.[7]

Decline and the Kelly gang (1870s–1880s)

The increasing push of settlement, increased police efficiency, improvements in rail transport and communications technology, such as telegraphy, made it more difficult for bushrangers to evade capture.

The scholarly, but eccentric Captain Moonlite (alias of Andrew George Scott) worked as an Anglican lay reader before turning to bushranging. Imprisoned in Ballarat for an armed bank robbery on the Victorian goldfields, he escaped, but was soon recaptured and received a ten-year sentence in HM Prison Pentridge. Within a year of his release in 1879, he and his gang held up the town of Wantabadgery in the Riverina. Two of the gang (including Moonlite's "soulmate" and alleged lover, James Nesbitt) and one trooper were killed when the police attacked. Scott was found guilty of murder and hanged along with one of his accomplices on 20 January 1880.

Among the last bushrangers was the Kelly Gang led by Ned Kelly, who were captured at Glenrowan in 1880, two years after they were outlawed.

Isolated outbreaks (1890s–1900s)

In 1900 the indigenous Governor Brothers terrorised much of northern New South Wales.[5]

"Boy bushrangers" (1910s–1920s)

The final phase of bushranging was sustained by the so-called "boy bushrangers"—youths who sought to commit crimes, mostly armed robberies, modelled on the exploits of their bushranging "heroes". The majority were captured alive without any fatalities.[8]

Public perception

In Australia, bushrangers often attract public sympathy (cf. the concept of social bandits). In Australian history and iconography bushrangers are held in some esteem in some quarters due to the harshness and anti-Catholicism of the colonial authorities whom they embarrassed, and the romanticism of the lawlessness they represented. Some bushrangers, most notably Ned Kelly in his Jerilderie letter, and in his final raid on Glenrowan, explicitly represented themselves as political rebels. Attitudes to Kelly, by far the most well-known bushranger, exemplify the ambivalent views of Australians regarding bushranging.

Legacy

The impact of bushrangers upon the areas in which they roamed is evidenced in the names of many geographical features in Australia, including Brady's Lookout, Moondyne Cave, Mount Tennent, Thunderbolts Way and Ward's Mistake. The districts of North East Victoria are unofficially known as Kelly Country.

Some bushrangers made a mark on Australian literature. While running from soldiers in 1818, Michael Howe dropped a knapsack containing a self-made book of kangaroo skin and written in kangaroo blood. In it was a dream diary and plans for a settlement he intended to found in the bush. Sometime bushranger Francis MacNamara, also known as Frank the Poet, wrote some of the best-known poems of the convict era. Several convict bushrangers also wrote autobiographies, including Jackey Jackey, Martin Cash and Owen Suffolk.

Cultural depictions

Jack Donahue was the first bushranger to have inspired bush ballads, including "Bold Jack Donahue" and "The Wild Colonial Boy".[9] Ben Hall and his gang were the subject of several bush ballads, including "Streets of Forbes".

Early plays about bushrangers include David Burn's The Bushrangers (1829), William Leman Rede's Faith and Falsehood; or, The Fate of the Bushranger (1830), William Thomas Moncrieff's Van Diemen's Land: An Operatic Drama (1831), The Bushrangers; or, Norwood Vale (1834) by Henry Melville, and The Bushrangers; or, The Tregedy of Donohoe (1835) by Charles Harpur.

In the late 19th century, E. W. Hornung and Hume Nisbet created popular bushranger novels within the conventions of the European "noble bandit" tradition. First serialised in The Sydney Mail in 1882–83, Rolf Boldrewood's bushranging novel Robbery Under Arms is considered a classic of Australian colonial literature. It also cited as an important influence on the American writer Owen Wister's 1902 novel The Virginian, widely regarded as the first Western.[10]

Bushrangers were a favoured subject of colonial artists such as S. T. Gill, Frank P. Mahony and William Strutt. Tom Roberts, one of the leading figures of the Heidelberg School (also known as Australian Impressionism), depicted bushrangers in some of his history paintings, including In a corner on the Macintyre (1894) and Bailed Up (1895), both set in Inverell, the area where Captain Thunderbolt was once active.

Although not the first Australian film with a bushranging theme, The Story of the Kelly Gang (1906)—the world's first feature-length narrative film—is regarded as having set the template for the genre. On the back of the film's success, its producers released one of two 1907 film adaptations of Boldrewood's Robbery Under Arms (the other being Charles MacMahon's version). Entering the first "golden age" of Australian cinema (1910–12), director John Gavin released two fictionalised accounts of real-life bushrangers: Moonlite (1910) and Thunderbolt (1910). The genre's popularity with audiences led to a spike of production unprecedented in world cinema.[11] Dan Morgan (1911) is notable for portraying its title character as an insane villain rather than a figure of romance. Ben Hall, Frank Gardiner, Captain Starlight, and numerous other bushrangers also received cinematic treatments at this time. Alarmed by what they saw as the glorification of outlawery, state governments imposed a ban on bushranger films in 1912, effectively removing "the entire folklore relating to bushrangers ... from the most popular form of cultural expression."[12] It is seen as a major reason for the collapse of a booming Australian film industry.[13] One of the few Australian films to escape the ban before it was lifted in the 1940s is the 1920 adaptation of Robbery Under Arms.[11] Also during this lull appeared American takes on the bushranger genre, including The Bushranger (1928), Stingaree (1934) and Captain Fury (1939).

Ned Kelly (1970) starred Mick Jagger in the title role. Dennis Hopper portrayed Dan Morgan in Mad Dog Morgan (1976). More recent bushranger films include Ned Kelly (2003), starring Heath Ledger, The Proposition (2005), written by Nick Cave, The Outlaw Michael Howe (2013), and The Legend of Ben Hall (2016).

Notable bushrangers

| Name | Lived | Area of activity | Fate | Portrait |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bluecap | c. 1835–? | New South Wales | Imprisoned, cause of death unknown | |

| Matthew Brady | 1799–1826 | Van Diemen's Land | Hanged | |

| Mary Ann Bugg | 1834–1905 | Northern New South Wales | Died of old age | |

| Richard Burgess | 1829–1866 | New South Wales Victoria | Hanged | |

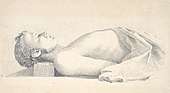

| Joe Byrne | 1857–1880 | North East Victoria | Shot by police |  |

| John Caesar | 1764–1796 | Sydney area | Shot | |

| Captain Melville | c. 1823–1857 | Goldfields region of Victoria | Suicide | |

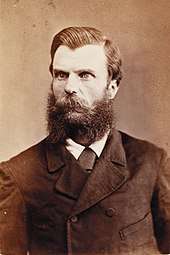

| Captain Moonlite | 1842–1880 | Victoria New South Wales | Hanged |  |

| Captain Thunderbolt | 1835–1870 | New South Wales | Shot by police |  |

| Martin Cash | c. 1808–1877 | Van Diemen's Land | Imprisoned, died a free man |  |

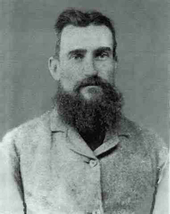

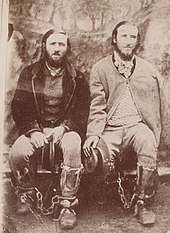

| Clarke brothers | 1840/1846-1867 | New South Wales | Hanged |  |

| Patrick Daley | 1844–? | New South Wales | Imprisoned, died a free man | |

| Edward Davis | ?–1841 | Northern New South Wales | Hanged | |

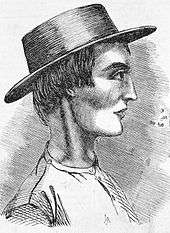

| Jack Donahue | c. 1806–1830 | Sydney area | Shot by police |  |

| Jack the Rammer | ?–1834 | South Eastern New South Wales | Shot | |

| John Dunn | 1846–1866 | Western New South Wales | Hanged |  |

| Ralph Entwistle | c. 1805–1830 | New South Wales | Hanged | |

| John Francis | c. 1825–? | Goldfields region of Victoria | Imprisoned, cause of death unknown | |

| Frank Gardiner | c. 1829–c. 1904 | Western New South Wales | Imprisoned, died a free man |  |

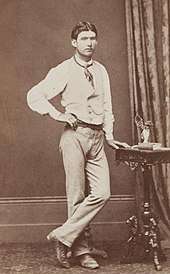

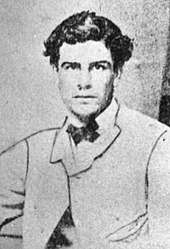

| John Gilbert | 1842–1865 | Western New South Wales | Shot by police | .jpg) |

| Jimmy Governor | 1875–1901 | New South Wales | Hanged | |

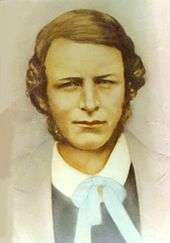

| Ben Hall | 1837–1865 | Western New South Wales | Shot by police |  |

| Steve Hart | 1859–1880 | North East Victoria | Possible suicide |  |

| Michael Howe | 1787–1818 | Van Diemen's Land | Shot by police | |

| Thomas Jeffries | ?–1826 | Van Diemen's Land | Hanged | |

| George Jones | c. 1815–1844 | Van Diemen's Land | Hanged | |

| Lawrence Kavenagh | c. 1805–1846 | Van Diemen's Land | Hanged |  |

| Dan Kelly | c. 1861–1880 | North East Victoria | Possible suicide |  |

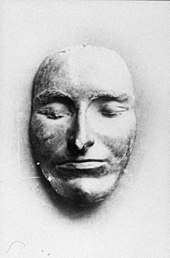

| Ned Kelly | c. 1854–1880 | North East Victoria | Hanged |  |

| Patrick Kenniff | 1865–1903 | Queensland | Hanged |  |

| John Kerney | c. 1844–1892 | South Australia | Imprisoned, died a free man | |

| Fred Lowry | 1836–1863 | New South Wales | Shot by police |  |

| John Lynch | 1813–1842 | New South Wales | Hanged | |

| James McPherson | 1842–1895 | Queensland | Imprisoned, died a free man |  |

| Moondyne Joe | c. 1828–1900 | Western Australia | Imprisoned, died a free man |  |

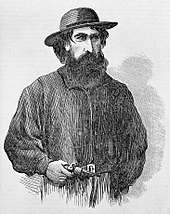

| Dan Morgan | c. 1830–1865 | New South Wales | Shot by police |  |

| Musquito | c. 1780–1825 | Van Diemen's Land | Hanged | |

| George Palmer | c. 1846–1869 | Queensland | Hanged |  |

| Alexander Pearce | 1790–1824 | Van Diemen's Land | Hanged | .jpg) |

| Sam Poo | ?–1865 | New South Wales | Hanged | |

| Harry Power | 1819–1891 | North East Victoria | Imprisoned, died a free man |  |

| Owen Suffolk | 1829–? | Victoria | Shot in prison | |

| John Tennant | 1794–1837 | New South Wales | Hanged | |

| John Vane | 1842–1906 | New South Wales | Imprisoned, died a free man | |

| William Westwood | 1820–1846 | New South Wales Van Diemen's Land | Hanged |  |

| John Whelan | c. 1805–1855 | Van Diemen's Land | Hanged |

References

- Ian Potter Museum collection: Bushrangers Archived 28 February 2011 at the Wayback Machine, u21museums.unimelb.edu.au. Retrieved on 9 January 2011.

- Hirst, John Bradley. Freedom on the Fatal Shore. Black Inc., 2008. ISBN 9781863952071, pp. 408–409.

- Wilson, Jane (14 April 2015). "Bushrangers in the Australian Dictionary of Biography", Australian Dictionary of Biography. Retrieved 14 June 2018.

- "Bushranging". The Australian Encyclopedia. 2 (5th edn. ed.). Australian Geographical Society. 1988. pp. 582–587. ISBN 1 862760004.

- "BUSHRANGERS OF AUSTRALIA" (PDF). National Museum of Australia. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 September 2007. Retrieved 16 April 2007.

- Boyce, James (2010). Van Diemen's Land. Black Inc.. ISBN 9781921825392. pp. 76–82.

- Baxter, Carol. Captain Thunderbolt and his Lady: the true story of bushrangers Frederick Ward and Mary Ann Bugg. Crows Nest, New South Wales: Allen & Unwin, 2011. ISBN 978-1-74237-287-7

- Johnson, Murray (2010). "Australian Bushrangers: Law, Retribution and the Public Imagination". In Robinson, Shirley; Lincoln, Robyn. Crime Over Time: Temporal Perspectives on Crime and Punishment in Australia. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. pp. 1–19. ISBN 9781443824569.

- "Old Windsor Road and Windsor Road Heritage Precincts". Heritage and conservation register. New South Wales Roads and Traffic Authority. Archived from the original on 3 September 2007. Retrieved 20 April 2007.

- Graulich, Melody; Tatum, Stephen. Reading the Virginian in the New West. Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press, 2003. ISBN 0-8032-7104-2

- Australian film and television chronology: The 1910s Archived 29 August 2016 at Wikiwix, Australian Screen. Retrieved 8 October 2015.

- Cooper, Ross; Pike, Andrew. Australian Film, 1900-1977: A Guide to Feature Film Production. Oxford University Press, 1998. ISBN 9780195507843.

- Reade, Eric (1970) Australian Silent Films: A Pictorial History of Silent Films from 1896 to 1926. Melbourne: Lansdowne Press, 59. See also Routt, William D. More Australian than Aristotelian:The Australian Bushranger Film,1904-1914. Senses of Cinema 18 (January-February), 2002 Archived 24 December 2010 at the Wayback Machine. The banning of bushranger films in NSW is fictionalised in Kathryn Heyman's 2006 novel, Captain Starlight's Apprentice.

External links

| Look up bushranger in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Bushrangers. |