Behavioral economics

Behavioral economics studies the effects of psychological, cognitive, emotional, cultural and social factors on the economic decisions of individuals and institutions and how those decisions vary from those implied by classical theory.[1][2]

| Part of a series on |

| Economics |

|---|

|

|

|

|

By application |

|

Notable economists |

|

Lists |

|

Glossary |

|

| Part of a series on |

| Nudge theory |

|---|

|

Social scientists |

|

Government programs |

|

Government agencies |

|

Related concepts |

|

Nudge theory in business |

Behavioral economics is primarily concerned with the bounds of rationality of economic agents. Behavioral models typically integrate insights from psychology, neuroscience and microeconomic theory.[3][4] The study of behavioral economics includes how market decisions are made and the mechanisms that drive public choice. The three prevalent themes in behavioral economics are:[5]

- Heuristics: Humans make 95% of their decisions using mental shortcuts or rules of thumb.

- Framing: The collection of anecdotes and stereotypes that make up the mental filters individuals rely on to understand and respond to events.

- Market inefficiencies: These include mis-pricing and non-rational decision making.

In 2002, psychologist Daniel Kahneman was awarded the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences "for having integrated insights from psychological research into economic science, especially concerning human judgment and decision-making under uncertainty."[6] In 2013, economist Robert J. Shiller received the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences "for his empirical analysis of asset prices" (within the field of behavioral finance).[7] In 2017, economist Richard Thaler was awarded the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences for "his contributions to behavioral economics and his pioneering work in establishing that people are predictably irrational in ways that defy economic theory."[8][9]

History

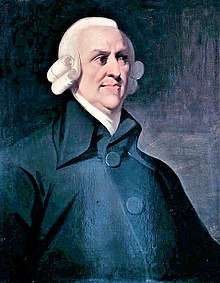

During the classical period of economics, microeconomics was closely linked to psychology. For example, Adam Smith wrote The Theory of Moral Sentiments, which proposed psychological explanations of individual behavior, including concerns about fairness and justice.[10] Jeremy Bentham wrote extensively on the psychological underpinnings of utility. Then, during the development of neo-classical economics, economists sought to reshape the discipline as a natural science, deducing behavior from assumptions about the nature of economic agents. They developed the concept of homo economicus, whose behavior was fundamentally rational.

Neo-classical economists did incorporate psychological explanations: this was true of Francis Edgeworth, Vilfredo Pareto and Irving Fisher. Economic psychology emerged in the 20th century in the works of Gabriel Tarde,[11] George Katona,[12] and Laszlo Garai.[13] Expected utility and discounted utility models began to gain acceptance, generating testable hypotheses about decision-making given uncertainty and intertemporal consumption, respectively. Observed and repeatable anomalies eventually challenged those hypotheses, and further steps were taken by Maurice Allais, for example, in setting out the Allais paradox, a decision problem he first presented in 1953 that contradicts the expected utility hypothesis.

In the 1960s cognitive psychology began to shed more light on the brain as an information processing device (in contrast to behaviorist models). Psychologists in this field, such as Ward Edwards,[14] Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman began to compare their cognitive models of decision-making under risk and uncertainty to economic models of rational behavior. Mathematical psychology reflects a longstanding interest in preference transitivity and the measurement of utility.[15]

Bounded rationality

Bounded rationality is the idea that when individuals make decisions, their rationality is limited by the tractability of the decision problem, their cognitive limitations and the time available. Decision-makers in this view act as satisficers, seeking a satisfactory solution rather than an optimal one. Herbert A. Simon proposed bounded rationality as an alternative basis for the mathematical modeling of decision-making. It complements "rationality as optimization", which views decision-making as a fully rational process of finding an optimal choice given the information available.[16] Simon used the analogy of a pair of scissors, where one blade represents human cognitive limitations and the other the "structures of the environment", illustrating how minds compensate for limited resources by exploiting known structural regularity in the environment.[16]

Bounded rationality implicates the idea that humans take shortcuts that may lead to suboptimal decision-making. Behavioral economists engage in mapping the decision shortcuts that agents use in order to help increase the effectiveness of human decision-making. One treatment of this idea comes from Cass Sunstein and Richard Thaler's Nudge.[17][18] Sunstein and Thaler recommend that choice architectures are modified in light of human agents' bounded rationality. A widely cited proposal from Sunstein and Thaler urges that healthier food be placed at sight level in order to increase the likelihood that a person will opt for that choice instead of less healthy option. Some critics of Nudge have lodged attacks that modifying choice architectures will lead to people becoming worse decision-makers.[19][20]

Prospect theory

In 1979, Kahneman and Tversky published Prospect Theory: An Analysis of Decision Under Risk, that used cognitive psychology to explain various divergences of economic decision making from neo-classical theory.[21] Prospect theory has two stages: an editing stage and an evaluation stage.

In the editing stage, risky situations are simplified using various heuristics. In the evaluation phase, risky alternatives are evaluated using various psychological principles that include:

- Reference dependence: When evaluating outcomes, the decision maker considers a "reference level." Outcomes are then compared to the reference point and classified as "gains" if greater than the reference point and "losses" if less than the reference point.

- Loss aversion: Losses are avoided more than equivalent gains are sought. In their 1992 paper, Kahneman and Tversky found the median coefficient of loss aversion to be about 2.25, i.e., losses hurt about 2.25 times more than equivalent gains reward.[22]

- Non-linear probability weighting: Decision makers overweigh small probabilities and underweigh large probabilities—this gives rise to the inverse-S shaped "probability weighting function."

- Diminishing sensitivity to gains and losses: As the size of the gains and losses relative to the reference point increase in absolute value, the marginal effect on the decision maker's utility or satisfaction falls.

Prospect theory is able to explain everything that the two main existing decision theories—expected utility theory and rank dependent utility theory—can explain. Further, prospect theory has been used to explain phenomena that existing decision theories have great difficulty in explaining. These include backward bending labor supply curves, asymmetric price elasticities, tax evasion and co-movement of stock prices and consumption.

In 1992, in the Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, Kahneman and Tversky gave a revised account of prospect theory that they called cumulative prospect theory.[22] The new theory eliminated the editing phase in prospect theory and focused just on the evaluation phase. Its main feature was that it allowed for non-linear probability weighting in a cumulative manner, which was originally suggested in John Quiggin's rank-dependent utility theory.

Psychological traits such as overconfidence, projection bias, and the effects of limited attention are now part of the theory. Other developments include a conference at the University of Chicago,[23] a special behavioral economics edition of the Quarterly Journal of Economics ("In Memory of Amos Tversky"), and Kahneman's 2002 Nobel Prize for having "integrated insights from psychological research into economic science, especially concerning human judgment and decision-making under uncertainty."[24]

Intertemporal choice

Behavioral economics has been applied to intertemporal choice, which is defined as making a decision and having the effects of such decision happening in a different time. Intertemporal choice behavior is largely inconsistent, as exemplified by George Ainslie's hyperbolic discounting—one of the prominently studied observations—and further developed by David Laibson, Ted O'Donoghue and Matthew Rabin. Hyperbolic discounting describes the tendency to discount outcomes in the near future more than outcomes in the far future. This pattern of discounting is dynamically inconsistent (or time-inconsistent), and therefore inconsistent with basic models of rational choice, since the rate of discount between time t and t+1 will be low at time t-1 when t is the near future, but high at time t when t is the present and time t+1 is the near future.

This pattern can also be explained through models of sub-additive discounting that distinguish the delay and interval of discounting: people are less patient (per-time-unit) over shorter intervals regardless of when they occur.

Other areas of research

Other branches of behavioral economics enrich the model of the utility function without implying inconsistency in preferences. Ernst Fehr, Armin Falk, and Rabin studied fairness, inequity aversion and reciprocal altruism, weakening the neoclassical assumption of perfect selfishness. This work is particularly applicable to wage setting. The work on "intrinsic motivation by Gneezy and Rustichini and "identity" by Akerlof and Kranton assumes that agents derive utility from adopting personal and social norms in addition to conditional expected utility. According to Aggarwal, in addition to behavioral deviations from rational equilibrium, markets are also likely to suffer from lagged responses, search costs, externalities of the commons, and other frictions making it difficult to disentangle behavioral effects in market behavior.[25]

"Conditional expected utility" is a form of reasoning where the individual has an illusion of control, and calculates the probabilities of external events and hence their utility as a function of their own action, even when they have no causal ability to affect those external events.[26][27]

Behavioral economics caught on among the general public with the success of books such as Dan Ariely's Predictably Irrational. Practitioners of the discipline have studied quasi-public policy topics such as broadband mapping.[28][29]

Applications for behavioral economics include the modeling of the consumer decision-making process for applications in artificial intelligence and machine learning. The Silicon Valley-based start-up Singularities is using the AGM postulates proposed by Alchourrón, Gärdenfors, and Makinson—the formalization of the concepts of beliefs and change for rational entities—in a symbolic logic to create a "machine learning and deduction engine that uses the latest data science and big data algorithms in order to generate the content and conditional rules (counterfactuals) that capture customer's behaviors and beliefs."[30]

Applications of behavioral economics also exist in other disciplines, for example in the area of supply chain management.[31]

Natural experiments

From a biological point of view, human behaviors are essentially the same during crises accompanied by stock market crashes and during bubble growth when share prices exceed historic highs. During those periods, most market participants see something new for themselves, and this inevitably induces a stress response in them with accompanying changes in their endocrine profiles and motivations. The result is quantitative and qualitative changes in behavior. This is one example where behavior affecting economics and finance can be observed and variably-contrasted using behavioral economics.

Behavioral economics' usefulness applies beyond environments similar to stock exchanges. Selfish-reasoning, 'adult behaviors', and similar, can be identified within criminal-concealment(s), and legal-deficiencies and neglect of different types can be observed and discovered. Awareness of indirect consequence (or lack of), at least in potential with different experimental models and methods, can be used as well—behavioral economics' potential uses are broad, but its reliability needs scrutiny. Underestimation of the role of novelty as a stressor is the primary shortcoming of current approaches for market research. It is necessary to account for the biologically determined diphasisms of human behavior in everyday low-stress conditions and in response to stressors.[32] Limitations of experimental methods (e.g. randomized control trials) and their use in economics were famously analyzed by Angus Deaton.[33]

Criticism

Critics of behavioral economics typically stress the rationality of economic agents.[34] A fundamental critique is provided by Maialeh (2019) who argues that no behavioral research can establish an economic theory. Examples provided on this account include pillars of behavioral economics such as satisficing behavior or prospect theory, which are confronted from the neoclassical perspective of utility maximization and expected utility theory respectively. The author shows that behavioral findings are hardly generalizable and that they do not disprove typical mainstream axioms related to rational behavior.[35]

Others note that cognitive theories, such as prospect theory, are models of decision-making, not generalized economic behavior, and are only applicable to the sort of once-off decision problems presented to experiment participants or survey respondents. Others argue that decision-making models, such as the endowment effect theory, that have been widely accepted behavioral economists may be erroneously established as a consequence of poor experimental design practices that do not adequately control subject misconceptions.[2][36][37][38]

A notable concern is that despite a great deal of rhetoric, no unified behavioral theory has yet been espoused: behavioral economists have proposed no unified theory.

David Gal has argued that many of these issues stem from behavioral economics being too concerned with understanding how behavior deviates from standard economic models rather than with understanding why people behave the way they do. Understanding why behavior occurs is necessary for the creation of generalizable knowledge, the goal of science. He has referred to behavioral economics as a "triumph of marketing" and particularly cited the example of loss aversion.[39]

Traditional economists are skeptical of the experimental and survey-based techniques that behavioral economics uses extensively. Economists typically stress revealed preferences over stated preferences (from surveys) in the determination of economic value. Experiments and surveys are at risk of systemic biases, strategic behavior and lack of incentive compatibility. Some researchers point out that participants of experiments conducted by behavioural economists are not representative enough and drawing broad conclusions on the basis of such experiments is not possible. An acronym WEIRD has been coined in order to describe the studies participants - as those, who come from Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, and Democratic societies.[40]

Responses

Matthew Rabin[41] dismisses these criticisms, countering that consistent results typically are obtained in multiple situations and geographies and can produce good theoretical insight. Behavioral economists, however, responded to these criticisms by focusing on field studies rather than lab experiments. Some economists see a fundamental schism between experimental economics and behavioral economics, but prominent behavioral and experimental economists tend to share techniques and approaches in answering common questions. For example, behavioral economists are investigating neuroeconomics, which is entirely experimental and has not been verified in the field.

The epistemological, ontological, and methodological components of behavioral economics are increasingly debated, in particular by historians of economics and economic methodologists.[42]

According to some researchers,[32] when studying the mechanisms that form the basis of decision-making, especially financial decision-making, it is necessary to recognize that most decisions are made under stress[43] because, "Stress is the nonspecific body response to any demands presented to it."[44]

Applied issues

Nudge theory

Nudge is a concept in behavioral science, political theory and economics which proposes positive reinforcement and indirect suggestions as ways to influence the behavior and decision making of groups or individuals. Nudging contrasts with other ways to achieve compliance, such as education, legislation or enforcement. The concept has influenced British and American politicians. Several nudge units exist around the world at the national level (UK, Germany, Japan and others) as well as at the international level (OECD, World Bank, UN).

The first formulation of the term and associated principles was developed in cybernetics by James Wilk before 1995 and described by Brunel University academic D. J. Stewart as "the art of the nudge" (sometimes referred to as micronudges[45]). It also drew on methodological influences from clinical psychotherapy tracing back to Gregory Bateson, including contributions from Milton Erickson, Watzlawick, Weakland and Fisch, and Bill O'Hanlon.[46] In this variant, the nudge is a microtargetted design geared towards a specific group of people, irrespective of the scale of intended intervention.

In 2008, Richard Thaler and Cass Sunstein's book Nudge: Improving Decisions About Health, Wealth, and Happiness brought nudge theory to prominence. It also gained a following among US and UK politicians, in the private sector and in public health.[47] The authors refer to influencing behaviour without coercion as libertarian paternalism and the influencers as choice architects.[48] Thaler and Sunstein defined their concept as:

A nudge, as we will use the term, is any aspect of the choice architecture that alters people's behavior in a predictable way without forbidding any options or significantly changing their economic incentives. To count as a mere nudge, the intervention must be easy and cheap to avoid. Nudges are not mandates. Putting fruit at eye level counts as a nudge. Banning junk food does not.

In this form, drawing on behavioral economics, the nudge is more generally applied to influence behaviour.

One of the most frequently cited examples of a nudge is the etching of the image of a housefly into the men's room urinals at Amsterdam's Schiphol Airport, which is intended to "improve the aim."[17]

Nudging techniques aim to use judgmental heuristics to our advantage. In other words, a nudge alters the environment so that when heuristic, or System 1, decision-making is used, the resulting choice will be the most positive or desired outcome.[49] An example of such a nudge is switching the placement of junk food in a store, so that fruit and other healthy options are located next to the cash register, while junk food is relocated to another part of the store.[50]

In 2008, the United States appointed Sunstein, who helped develop the theory, as administrator of the Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs.[48][51][52]

Notable applications of nudge theory include the formation of the British Behavioural Insights Team in 2010. It is often called the "Nudge Unit", at the British Cabinet Office, headed by David Halpern.[53]

Both Prime Minister David Cameron and President Barack Obama sought to employ nudge theory to advance domestic policy goals during their terms.[54]

In Australia, the government of New South Wales established a Behavioural Insights community of practice.[55]

Nudge theory has also been applied to business management and corporate culture, such as in relation to health, safety and environment (HSE) and human resources. Regarding its application to HSE, one of the primary goals of nudge is to achieve a "zero accident culture."[56]

Leading Silicon Valley companies are forerunners in applying nudge theory in a corporate setting. These companies are using nudges in various forms to increase the productivity and happiness of employees. Recently, further companies are gaining interest in using what is called "nudge management" to improve the productivity of their white-collar workers.[57]

Behavioral insights and nudges are currently used in many countries around the world.[58]

Criticisms

Nudging has also been criticised. Tammy Boyce, from public health foundation The King's Fund, has said: "We need to move away from short-term, politically motivated initiatives such as the 'nudging people' idea, which is not based on any good evidence and doesn't help people make long-term behaviour changes."[59]

Cass Sunstein has responded to critiques at length in his The Ethics of Influence[60] making the case in favor of nudging against charges that nudges diminish autonomy,[61] threaten dignity, violate liberties, or reduce welfare. Ethicists have debated this rigorously.[62] These charges have been made by various participants in the debate from Bovens[63] to Goodwin.[64] Wilkinson for example charges nudges for being manipulative, while others such as Yeung question their scientific credibility.[65]

Some, such as Hausman & Welch[66] have inquired whether nudging should be permissible on grounds of (distributive) justice; Lepenies & Malecka[67] have questioned whether nudges are compatible with the rule of law. Similarly, legal scholars have discussed the role of nudges and the law.[68][69]

Behavioral economists such as Bob Sugden have pointed out that the underlying normative benchmark of nudging is still homo economicus, despite the proponents' claim to the contrary.[70]

It has been remarked that nudging is also a euphemism for psychological manipulation as practiced in social engineering.[71][72]

There exists an anticipation and, simultaneously, implicit criticism of the nudge theory in works of Hungarian social psychologists who emphasize the active participation in the nudge of its target (Ferenc Merei[73] and Laszlo Garai[13]).

Behavioral finance

The central issue in behavioral finance is explaining why market participants make irrational systematic errors contrary to assumption of rational market participants.[1] Such errors affect prices and returns, creating market inefficiencies. The study of behavioral finance also investigates how other participants take advantage (arbitrage) of such errors and market inefficiencies.

Behavioral finance highlights inefficiencies, such as under- or over-reactions to information, as causes of market trends and, in extreme cases, of bubbles and crashes. Such reactions have been attributed to limited investor attention, overconfidence, overoptimism, mimicry (herding instinct) and noise trading. Technical analysts consider behavioral finance to be behavioral economics' "academic cousin" and the theoretical basis for technical analysis.[74]

Other key observations include the asymmetry between decisions to acquire or keep resources, known as the "bird in the bush" paradox, and loss aversion, the unwillingness to let go of a valued possession. Loss aversion appears to manifest itself in investor behavior as a reluctance to sell shares or other equity if doing so would result in a nominal loss. It may also help explain why housing prices rarely/slowly decline to market clearing levels during periods of low demand.

Benartzi and Thaler, applying a version of prospect theory, claim to have solved the equity premium puzzle, something conventional finance models so far have been unable to do.[75] Experimental finance applies the experimental method, e.g., creating an artificial market through some kind of simulation software to study people's decision-making process and behavior in financial markets.

Quantitative behavioral finance

Quantitative behavioral finance uses mathematical and statistical methodology to understand behavioral biases. In marketing research, a study shows little evidence that escalating biases impact marketing decisions.[76] Leading contributors include Gunduz Caginalp (Editor of the Journal of Behavioral Finance from 2001–04), and collaborators include 2002 Nobel Laureate Vernon Smith, David Porter, Don Balenovich,[77] Vladimira Ilieva and Ahmet Duran,[78] and Ray Sturm.[79]

Financial models

Some financial models used in money management and asset valuation incorporate behavioral finance parameters. Examples:

- Thaler's model of price reactions to information, with three phases (underreaction, adjustment, and overreaction), creating a price trend.

- One characteristic of overreaction is that average returns following announcements of good news is lower than following bad news. In other words, overreaction occurs if the market reacts too strongly or for too long to news, thus requiring an adjustment in the opposite direction. As a result, outperforming assets in one period is likely to underperform in the following period. This also applies to customers' irrational purchasing habits.[80]

- The stock image coefficient.

Criticisms

Critics such as Eugene Fama typically support the efficient-market hypothesis. They contend that behavioral finance is more a collection of anomalies than a true branch of finance and that these anomalies are either quickly priced out of the market or explained by appealing to market microstructure arguments. However, individual cognitive biases are distinct from social biases; the former can be averaged out by the market, while the other can create positive feedback loops that drive the market further and further from a "fair price" equilibrium. Similarly, for an anomaly to violate market efficiency, an investor must be able to trade against it and earn abnormal profits; this is not the case for many anomalies.[81]

A specific example of this criticism appears in some explanations of the equity premium puzzle. It is argued that the cause is entry barriers (both practical and psychological) and that returns between stocks and bonds should equalize as electronic resources open up the stock market to more traders.[82] In response, others contend that most personal investment funds are managed through superannuation funds, minimizing the effect of these putative entry barriers. In addition, professional investors and fund managers seem to hold more bonds than one would expect given return differentials.

Behavioral game theory

Behavioral game theory, invented by Colin Camerer, analyzes interactive strategic decisions and behavior using the methods of game theory,[83] experimental economics, and experimental psychology. Experiments include testing deviations from typical simplifications of economic theory such as the independence axiom[84] and neglect of altruism,[85] fairness,[86] and framing effects.[87] On the positive side, the method has been applied to interactive learning[88] and social preferences.[89][90][91] As a research program, the subject is a development of the last three decades.[92][93][94][95][96][97][98]

Economic reasoning in animals

A handful of comparative psychologists have attempted to demonstrate quasi-economic reasoning in non-human animals. Early attempts along these lines focus on the behavior of rats and pigeons. These studies draw on the tenets of comparative psychology, where the main goal is to discover analogs to human behavior in experimentally-tractable non-human animals. They are also methodologically similar to the work of Ferster and Skinner.[99] Methodological similarities aside, early researchers in non-human economics deviate from behaviorism in their terminology. Although such studies are set up primarily in an operant conditioning chamber using food rewards for pecking/bar-pressing behavior, the researchers describe pecking and bar-pressing not in terms of reinforcement and stimulus-response relationships but instead in terms of work, demand, budget, and labor. Recent studies have adopted a slightly different approach, taking a more evolutionary perspective, comparing economic behavior of humans to a species of non-human primate, the capuchin monkey.[100]

Animal studies

Many early studies of non-human economic reasoning were performed on rats and pigeons in an operant conditioning chamber. These studies looked at things like peck rate (in the case of the pigeon) and bar-pressing rate (in the case of the rat) given certain conditions of reward. Early researchers claim, for example, that response pattern (pecking/bar-pressing rate) is an appropriate analogy to human labor supply.[101] Researchers in this field advocate for the appropriateness of using animal economic behavior to understand the elementary components of human economic behavior.[102] In a paper by Battalio, Green, and Kagel,[101] they write,

Space considerations do not permit a detailed discussion of the reasons why economists should take seriously the investigation of economic theories using nonhuman subjects....[Studies of economic behavior in non-human animals] provide a laboratory for identifying, testing, and better understanding general laws of economic behavior. Use of this laboratory is predicated on the fact that behavior, as well as structure, vary continuously across species, and that principles of economic behavior would be unique among behavioral principles if they did not apply, with some variation, of course, to the behavior of nonhumans.

Labor supply

The typical laboratory environment to study labor supply in pigeons is set up as follows. Pigeons are first deprived of food. Since the animals become hungry, food becomes highly desired. The pigeons are then placed in an operant conditioning chamber and through orienting and exploring the environment of the chamber they discover that by pecking a small disk located on one side of the chamber, food is delivered to them. In effect, pecking behavior becomes reinforced, as it is associated with food. Before long, the pigeon pecks at the disk (or stimulus) regularly.

In this circumstance, the pigeon is said to "work" for the food by pecking. The food, then, is thought of as the currency. The value of the currency can be adjusted in several ways, including the amount of food delivered, the rate of food delivery and the type of food delivered (some foods are more desirable than others).

Economic behavior similar to that observed in humans is discovered when the hungry pigeons stop working/work less when the reward is reduced. Researchers argue that this is similar to labor supply behavior in humans. That is, like humans (who, even in need, will only work so much for a given wage), the pigeons demonstrate decreases in pecking (work) when the reward (value) is reduced.[101]

Demand

In human economics, a typical demand curve has negative slope. This means that as the price of a certain good increase, the amount that consumers are willing and able to purchase decreases. Researchers studying the demand curves of non-human animals, such as rats, also find downward slopes.

Researchers have studied demand in rats in a manner distinct from studying labor supply in pigeons. Specifically, in an operant conditioning chamber containing rats as experimental subjects, we require them to press a bar, instead of pecking a small disk, to receive a reward. The reward can be food (reward pellets), water, or a commodity drink such as cherry cola. Unlike in previous pigeon studies, where the work analog was pecking and the monetary analog was a reward, the work analog in this experiment is bar-pressing. Under these circumstances, the researchers claim that changing the number of bar presses required to obtain a commodity item is analogous to changing the price of a commodity item in human economics.[103]

In effect, results of demand studies in non-human animals show that, as the bar-pressing requirement (cost) increase, the number of times an animal presses the bar equal to or greater than the bar-pressing requirement (payment) decreases.

Evolutionary psychology

An evolutionary psychology perspective states that many of the perceived limitations in rational choice can be explained as being rational in the context of maximizing biological fitness in the ancestral environment, but not necessarily in the current one. Thus, when living at subsistence level where a reduction of resources may result in death, it may have been rational to place a greater value on preventing losses than on obtaining gains. It may also explain behavioral differences between groups, such as males being less risk-averse than females since males have more variable reproductive success than females. While unsuccessful risk-seeking may limit reproductive success for both sexes, males may potentially increase their reproductive success from successful risk-seeking much more than females can.[104]

Artificial intelligence

Much of the decisions are more and more made either by human beings with the assistance of artificial intelligent machines or wholly made by these machines. Tshilidzi Marwala and Evan Hurwitz in their book,[105] studied the utility of behavioral economics in such situations and concluded that these intelligent machines reduce the impact of bounded rational decision making. In particular, they observed that these intelligent machines reduce the degree of information asymmetry in the market, improve decision making and thus making markets more rational.

The use of AI machines in the market in applications such as online trading and decision making has changed major economic theories.[105] Other theories where AI has had impact include in rational choice, rational expectations, game theory, Lewis turning point, portfolio optimization and counterfactual thinking.

Related fields

Experimental economics

Experimental economics is the application of experimental methods, including statistical, econometric, and computational,[106] to study economic questions. Data collected in experiments are used to estimate effect size, test the validity of economic theories, and illuminate market mechanisms. Economic experiments usually use cash to motivate subjects, in order to mimic real-world incentives. Experiments are used to help understand how and why markets and other exchange systems function as they do. Experimental economics have also expanded to understand institutions and the law (experimental law and economics).[107]

A fundamental aspect of the subject is design of experiments. Experiments may be conducted in the field or in laboratory settings, whether of individual or group behavior.[108]

Variants of the subject outside such formal confines include natural and quasi-natural experiments.[109]

Neuroeconomics

Neuroeconomics is an interdisciplinary field that seeks to explain human decision making, the ability to process multiple alternatives and to follow a course of action. It studies how economic behavior can shape our understanding of the brain, and how neuroscientific discoveries can constrain and guide models of economics.[110]

It combines research methods from neuroscience, experimental and behavioral economics, and cognitive and social psychology.[111] As research into decision-making behavior becomes increasingly computational, it has also incorporated new approaches from theoretical biology, computer science, and mathematics. Neuroeconomics studies decision making by using a combination of tools from these fields so as to avoid the shortcomings that arise from a single-perspective approach. In mainstream economics, expected utility (EU) and the concept of rational agents are still being used. Many economic behaviors are not fully explained by these models, such as heuristics and framing.[112]

Behavioral economics emerged to account for these anomalies by integrating social, cognitive, and emotional factors in understanding economic decisions. Neuroeconomics adds another layer by using neuroscientific methods in understanding the interplay between economic behavior and neural mechanisms. By using tools from various fields, some scholars claim that neuroeconomics offers a more integrative way of understanding decision making.[110]

Notable people

Economics

- George Akerlof

- Werner De Bondt

- Paul De Grauwe[113]

- Linda C. Babcock

- Douglas Bernheim[114]

- Colin Camerer

- Armin Falk

- Urs Fischbacher

- Tshilidzi Marwala

- Susan E. Mayer

- Ernst Fehr

- Simon Gächter

- Uri Gneezy[115]

- David Laibson

- Louis Lévy-Garboua

- John A. List

- George Loewenstein

- Sendhil Mullainathan

- John Quiggin

- Matthew Rabin

- Reinhard Selten

- Herbert A. Simon

- Vernon L. Smith

- Robert Sugden[116]

- Larry Summers

- Richard Thaler

Finance

- Malcolm Baker

- Nicholas Barberis

- Gunduz Caginalp

- David Hirshleifer

- Andrew Lo

- Michael Mauboussin

- Terrance Odean

- Richard L. Peterson

- Charles Plott

- Robert Prechter

- Hersh Shefrin

- Robert Shiller

- Andrei Shleifer

- Robert Vishny

Psychology

- George Ainslie

- Dan Ariely[117]

- Ed Diener

- Ward Edwards

- Laszlo Garai

- Gerd Gigerenzer

- Daniel Kahneman

- Ariel Kalil

- George Katona

- Walter Mischel

- Drazen Prelec

- Eldar Shafir

- Paul Slovic

- John Staddon[118]

- Amos Tversky

See also

- Adaptive market hypothesis

- Animal Spirits (Keynes)

- Behavioralism

- Behavioral analysis of markets

- Behavioral operations research

- Big Five personality traits

- Confirmation bias

- Cultural economics

- Culture change

- Economic sociology

- Emotional bias

- Fuzzy-trace theory

- Hindsight bias

- Homo reciprocans

- Important publications in behavioral economics

- List of cognitive biases

- Market sentiment

- Methodological individualism

- Nudge theory

- Observational techniques

- Praxeology

- Priority heuristic

- Regret theory

- Repugnancy costs

- Socioeconomics

- Socionomics

Citations

- Lin, Tom C. W. (16 April 2012). "A Behavioral Framework for Securities Risk". Seattle University Law Review. SSRN. SSRN 2040946.

- Zeiler, Kathryn; Teitelbaum, Joshua (2018-03-30). "Research Handbook on Behavioral Law and Economics". Books.

- "Search of behavioural economics". in Palgrave

- Minton, Elizabeth A.; Kahle, Lynn R. (2013). Belief Systems, Religion, and Behavioral Economics: Marketing in Multicultural Environments. Business Expert Press. ISBN 978-1-60649-704-3.

- Shefrin 2002.

- "The Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel 2002". Nobel Foundation. Retrieved 2008-10-14.

- "The Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel 2013". Nobel Foundation. Retrieved 2016-07-01.

- Appelbaum, Binyamin (2017-10-09). "Nobel in Economics is Awarded to Richard Thaler". The New York Times. Retrieved 2017-11-04.

- Carrasco-Villanueva, Marco (2017-10-18). "Richard Thaler y el auge de la Economía Conductual". Lucidez (in Spanish). Retrieved 2018-10-31.

- Ashraf, Nava; Camerer, Colin F.; Loewenstein, George (2005). "Adam Smith, Behavioral Economist" (PDF). Journal of Economic Perspectives. 19 (3): 131–45. doi:10.1257/089533005774357897. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-04-17. Retrieved 2011-12-20..

- Tarde, G. (1902). "Psychologie économique" (in French).

- Katona, George (2011). The Powerful Consumer: Psychological Studies of the American Economy. Literary Licensing, LLC. ISBN 978-1-258-21844-7.

- Garai, Laszlo (2017). "The Double-Storied Structure of Social Identity". Reconsidering Identity Economics. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-137-52561-1.

- "Ward Edward Papers". Archival Collections. Archived from the original on 2008-04-16. Retrieved 2008-04-25.

- Luce 2000.

- Gigerenzer, Gerd; Selten, Reinhard (2002). Bounded Rationality: The Adaptive Toolbox. MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-57164-7.

- Thaler, Richard H., Sunstein, Cass R. (April 8, 2008). Nudge: Improving Decisions about Health, Wealth, and Happiness. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-14-311526-7. OCLC 791403664.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Thaler, Richard H., Sunstein, Cass R. and Balz, John P. (April 2, 2010). Choice Architecture. doi:10.2139/ssrn.1583509. SSRN 1583509.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Wright, Joshua; Ginsberg, Douglas (February 16, 2012). "Free to Err?: Behavioral Law and Economics and its Implications for Liberty". Library of Law & Liberty.

- Sunstein, Cass (2009). Going to Extremes: How Like Minds Unite and Divide. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199793143.

- Kahneman & Diener 2003.

- Tversky, Amos; Kahneman, Daniel (1992). "Advances in Prospect Theory: Cumulative Representation of Uncertaintly". Journal of Risk and Uncertainty. 5 (4): 297–323. doi:10.1007/BF00122574. ISSN 0895-5646.Abstract.

- Hogarth & Reder 1987.

- "Nobel Laureates 2002". Nobelprize.org. Archived from the original on 10 April 2008. Retrieved 2008-04-25.

- Aggarwal, Raj (2014). "Animal Spirits in Financial Economics: A Review of Deviations from Economic Rationality". International Review of Financial Analysis. 32 (1): 179–87. doi:10.1016/j.irfa.2013.07.018.

- Grafstein R (1995). "Rationality as Conditional Expected Utility Maximization". Political Psychology. 16 (1): 63–80. doi:10.2307/3791450. JSTOR 3791450.

- Shafir E, Tversky A (1992). "Thinking through uncertainty: nonconsequential reasoning and choice". Cognitive Psychology. 24 (4): 449–74. doi:10.1016/0010-0285(92)90015-T. PMID 1473331.

- "US National Broadband Plan: good in theory". Telco 2.0. March 17, 2010. Retrieved 2010-09-23.

... Sara Wedeman's awful experience with this is instructive....

- Cook, Gordon; Wedeman, Sara (July 1, 2009). "Connectivity, the Five Freedoms, and Prosperity". Community Broadband Networks. Retrieved 2010-09-23.

- "Singluarities Our Company". Singular Me, LLC. 2017. Archived from the original on 2017-11-12. Retrieved 2017-07-12.

... machine learning and deduction engine that uses the latest data science and big data algorithms in order to generate the content and conditional rules (counterfactuals) that capture customer's behaviors and beliefs....

- Timm Schorsch, Carl Marcus Wallenburg, Andreas Wieland, (2017) "The human factor in SCM: Introducing a meta-theory of behavioral supply chain management", International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management, Vol. 47 Issue: 4, pp. 238-262, https://doi.org/10.1108/IJPDLM-10-2015-0268

- Sarapultsev, A.; Sarapultsev, P. (2014). "Novelty, Stress, and Biological Roots in Human Market Behavior". Behavioral Sciences. 4 (1): 53–69. doi:10.3390/bs4010053. PMC 4219248. PMID 25379268.

- Blattman, Christopher. "Why Angus Deaton Deserved the Nobel Prize in Economics". Foreign Policy. Retrieved 18 February 2020.

- Myagkov; Plott (1997). "Exchange Economies and Loss Exposure: Experiments Exploring Prospect Theory and Competitive Equilibria in Market Environments" (PDF). Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Maialeh, Robin (2019). "Generalization of results and neoclassical rationality: unresolved controversies of behavioural economics methodology". Quality & Quantity. 53 (4): 1743–1761. doi:10.1007/s11135-019-00837-1.

- Klass, Greg; Zeiler, Kathryn (2013-01-01). "Against Endowment Theory: Experimental Economics and Legal Scholarship". UCLA Law Review. 61 (1): 2.

- Zeiler, Kathryn (2011-01-01). "The Willingness to Pay-Willingness to Accept Gap, the 'Endowment Effect,' Subject Misconceptions, and Experimental Procedures for Eliciting Valuations: Reply". American Economic Review. 101: 1012.

- Zeiler, Kathryn (2005-01-01). "The Willingness to Pay-Willingness to Accept Gap, the 'Endowment Effect,' Subject Misconceptions, and Experimental Procedures for Eliciting Valuations". American Economic Review. 95: 530.

- "Opinion | Why Is Behavioral Economics So Popular?". Retrieved 2018-11-16.

- Joseph Henrich, Steven J. Heine, Ara Norenzayan, The weirdest people in the world?, „Behavioral and brain sciences”, 2010.

- Rabin 1998, pp. 11–46.

- Kersting, Felix; Obst, Daniel (10 April 2016). "Behavioral Economics". Exploring Economics.

- Zhukov, D.A. (2007). Biologija Povedenija. Gumoral’nye Mehanizmy [Biology of Behavior. Humoral Mechanisms];. St. Petersburg, Russia: Rech.CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link)

- Selye, Hans (2013). Stress in Health and Disease. Elsevier Science. ISBN 978-1-4831-9221-5.

- Wilk, J. (1999), "Mind, nature and the emerging science of change: An introduction to metamorphology.", in G. Cornelis; S. Smets; J. Van Bendegem (eds.), EINSTEIN MEETS MAGRITTE: An Interdisciplinary Reflection on Science, Nature, Art, Human Action and Society: Metadebates on science, 6, Springer Netherlands, pp. 71–87, doi:10.1007/978-94-017-2245-2_6, ISBN 978-90-481-5242-1

- O'Hanlon, B.; Wilk, J. (1987), Shifting contexts : The generation of effective psychotherapy., New York, N.Y.: Guilford Press.

- See: Dr. Jennifer Lunt and Malcolm Staves Archived 2012-04-30 at the Wayback Machine

- Andrew Sparrow (2008-08-22). "Speak 'Nudge': The 10 key phrases from David Cameron's favorite book". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 2009-09-09.

- Campbell-Arvai, V; Arvai, J.; Kalof, L. (2014). "Motivating sustainable food choices: the role of nudges, value orientation, and information provision". Environment and Behavior. 46 (4): 453–475. doi:10.1177/0013916512469099.

- Kroese, F.; Marchiori, D.; de Ridder, D. (2016). "Nudging healthy food choices: a field experiment at the train station" (PDF). Journal of Public Health. 38 (2): e133–7. doi:10.1093/pubmed/fdv096. PMID 26186924.

- Carol Lewis (2009-07-22). "Why Barack Obama and David Cameron are keen to 'nudge' you". The Times. London. Retrieved 2009-09-09.

- James Forsyth (2009-07-16). "Nudge, nudge: meet the Cameroons' new guru". The Spectator. Archived from the original on 2009-01-24. Retrieved 2009-09-09.

- "Who we are". The Behavioural Insights Team.

- "First Obama, now Cameron embraces 'nudge theory'". The Independent. 12 August 2010.

- "Behavioural Insights". bi.dpc.nsw.gov.au. Department of Premier and Cabinet.

- Marsh, Tim (January 2012). "Cast No Shadow" (PDF). Rydermarsh.co.uk. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 October 2017.

- Ebert, Philip; Freibichler, Wolfgang (2017). "Nudge management: applying behavioural science to increase knowledge worker productivity". Journal of Organization Design. 6:4. doi:10.1186/s41469-017-0014-1. hdl:1893/25187.

- Carrasco-Villanueva, Marco (2016). "中国的环境公共政策:一个行为经济学的选择 [Environmental Public Policies in China: An Opportunity for Behavioral Economics]". In 上海社会科学院 [Shanghai Academy of Social Sciences] (ed.). 2016上海青年汉学家研修计划论文集 (in Chinese). 中国社会科学出版社 [China Social Sciences Press]. pp. 368–392. ISBN 978-1-234-56789-7.

- Lakhani, Nina (December 7, 2008). "Unhealthy lifestyles here to stay, in spite of costly campaigns". The Independent. London. Retrieved April 28, 2010.

- Sunstein, Cass R. (2016-08-24). The Ethics of Influence: Government in the Age of Behavioral Science. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781107140707.

- Schubert, Christian (2015-10-12). "On the Ethics of Public Nudging: Autonomy and Agency". Rochester, NY. SSRN 2672970. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Barton, Adrien; Grüne-Yanoff, Till (2015-09-01). "From Libertarian Paternalism to Nudging—and Beyond". Review of Philosophy and Psychology. 6 (3): 341–359. doi:10.1007/s13164-015-0268-x. ISSN 1878-5158.

- Bovens, Luc (2009). "The Ethics of Nudge". Preference Change. Theory and Decision Library. Springer, Dordrecht. pp. 207–219. doi:10.1007/978-90-481-2593-7_10. ISBN 9789048125920.

- Goodwin, Tom (2012-06-01). "Why We Should Reject 'Nudge'". Politics. 32 (2): 85–92. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9256.2012.01430.x. ISSN 0263-3957.

- Yeung, Karen (2012-01-01). "Nudge as Fudge". The Modern Law Review. 75 (1): 122–148. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2230.2012.00893.x. ISSN 1468-2230.

- Hausman, Daniel M.; Welch, Brynn (2010-03-01). "Debate: To Nudge or Not to Nudge*". Journal of Political Philosophy. 18 (1): 123–136. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9760.2009.00351.x. ISSN 1467-9760.

- Lepenies, Robert; Małecka, Magdalena (2015-09-01). "The Institutional Consequences of Nudging – Nudges, Politics, and the Law". Review of Philosophy and Psychology. 6 (3): 427–437. doi:10.1007/s13164-015-0243-6. ISSN 1878-5158.

- Alemanno, A.; Spina, A. (2014-04-01). "Nudging legally: On the checks and balances of behavioral regulation". International Journal of Constitutional Law. 12 (2): 429–456. doi:10.1093/icon/mou033. ISSN 1474-2640.

- Kemmerer, Alexandra; Möllers, Christoph; Steinbeis, Maximilian; Wagner, Gerhard (2016-07-15). "Choice Architecture in Democracies: Exploring the Legitimacy of Nudging - Preface". Rochester, NY. SSRN 2810229. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Sugden, Robert (2017-06-01). "Do people really want to be nudged towards healthy lifestyles?". International Review of Economics. 64 (2): 113–123. doi:10.1007/s12232-016-0264-1. ISSN 1865-1704.

- Cass R. Sunstein. "NUDGING AND CHOICE ARCHITECTURE: ETHICAL CONSIDERATIONS" (PDF). Law.harvard.edu. Retrieved 11 October 2017.

- "A nudge in the right direction? How we can harness behavioural economics". 1 December 2015.

- MÉREI, Ferenc (1987). "A perem-helyzet egyik változata: a szociálpszichológiai kontúr" [A variant of the edge-position: the contour social psychological]. Pszichológia (in Hungarian). 1: 1–5.

- Kirkpatrick & Dahlquist 2007, p. 49.

- Benartzi & Thaler 1995.

- J. Scott Armstrong, Nicole Coviello and Barbara Safranek (1993). "Escalation Bias: Does It Extend to Marketing?" (PDF). Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science. 21 (3): 247–352. doi:10.1177/0092070393213008.

- "Dr. Donald A. Balenovich". Indiana University of Pennsylvania, Mathematics Department.

- "Ahmet Duran". Department of Mathematics, University of Michigan-Ann Arbor.

- "Dr Ray R. Sturm, CPA". College of Business Administration. Archived from the original on September 20, 2006.

- Tang, David (6 May 2013). "Why People Won't Buy Your Product Even Though It's Awesome". Flevy. Retrieved 31 May 2013.

- "Fama on Market Efficiency in a Volatile Market". Archived from the original on March 24, 2010.

- See Freeman, 2004 for a review

- Auman, Robert. "Game Theory". in Palgrave

- Camerer, Colin; Ho, Teck-Hua (March 1994). "Violations of the betweenness axiom and nonlinearity in probability". Journal of Risk and Uncertainty. 8 (2): 167–96. doi:10.1007/bf01065371.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Andreoni, James; et al. "Altruism in experiments". in Palgrave

- Young, H. Peyton. "Social norms". in Palgrave

- Camerer, Colin (1997). "Progress in behavioral game theory". Journal of Economic Perspectives. 11 (4): 172. doi:10.1257/jep.11.4.167. Archived from the original on 2017-12-23. Retrieved 2014-10-31.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) Pdf version.

- Ho, Teck H. (2008). "Individual learning in games". in Palgrave

- Dufwenberg, Martin; Kirchsteiger, Georg (2004). "A Theory of Sequential reciprocity". Games and Economic Behavior. 47 (2): 268–98. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.124.9311. doi:10.1016/j.geb.2003.06.003.

- Gul, Faruk (2008). "Behavioural economics and game theory". in Palgrave

- Camerer, Colin F. (2008). "Behavioral game theory". in Palgrave

- Camerer, Colin (2003). Behavioral game theory: experiments in strategic interaction. New York, New York Princeton, New Jersey: Russell Sage Foundation Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-09039-9.

- Loewenstein, George; Rabin, Matthew (2003). Advances in Behavioral Economics 1986–2003 papers. Princeton.

- Fudenberg, Drew (2006). "Advancing Beyond Advances in Behavioral Economics". Journal of Economic Literature. 44 (3): 694–711. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.1010.3674. doi:10.1257/jel.44.3.694. JSTOR 30032349.

- Crawford, Vincent P. (1997). Kreps, David M; Wallis, Kenneth F (eds.). Theory and Experiment in the Analysis of Strategic Interaction (PDF). Advances in Economics and Econometrics: Theory and Applications. Cambridge. pp. 206–42. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.298.3116. doi:10.1017/CCOL521580110.007. ISBN 9781139052009.

- Shubik, Martin (2002). "Chapter 62 Game theory and experimental gaming". In Aumann and, R.; Hart, S. (eds.). Game Theory and Experimental Gaming. Handbook of Game Theory with Economic Applications. 3. Elsevier. pp. 2327–51. doi:10.1016/S1574-0005(02)03025-4. ISBN 9780444894281.

- Plott, Charles R.; Smith, Vernon l (2002). "45–66". In Aumann and, R.; Hart, S. (eds.). Game Theory and Experimental Gaming. Handbook of Game Theory with Economic Applications. Handbook of Experimental Economics Results. 4. Elsevier. pp. 387–615. doi:10.1016/S1574-0722(07)00121-7. ISBN 9780444826428.

- Games and Economic Behavior (journal), Elsevier. Online

- Ferster, C. B.; et al. (1957). Schedules of Reinforcement. New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts.

- Chen, M. K.; et al. (2006). "How Basic Are Behavioral Biases? Evidence from Capuchin Monkey Trading Behavior". Journal of Political Economy. 114 (3): 517–37. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.594.4936. doi:10.1086/503550.

- Battalio, R. C.; et al. (1981). "Income-Leisure Tradeoffs of Animal Workers". American Economic Review. 71 (4): 621–32. JSTOR 1806185.

- Kagel, John H.; Battalio, Raymond C.; Green, Leonard (1995). Economic Choice Theory: An Experimental Analysis of Animal Behavior. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-45488-9.

- Kagel, J. H.; et al. (1981). "Demand Curves for Animal Consumers". Quarterly Journal of Economics. 96 (1): 1–16. doi:10.2307/2936137. JSTOR 2936137.

- Paul H. Rubin and C. Monica Capra. The evolutionary psychology of economics. In Roberts, S. C. (2011). Roberts, S. Craig (ed.). Applied Evolutionary Psychology. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199586073.001.0001. ISBN 9780199586073.

- Marwala, Tshilidzi; Hurwitz, Evan (2017). Artificial Intelligence and Economic Theory: Skynet in the Market. London: Springer. ISBN 978-3-319-66104-9.

- Alvin E. Roth, 2002. "The Economist as Engineer: Game Theory, Experimentation, and Computation as Tools for Design Economics," Econometrica, 70(4), pp. 1341–1378 Archived 2004-04-14 at the Wayback Machine.

- See, e.g., Grechenig, K., Nicklisch, A., & Thöni, C. (2010). Punishment despite reasonable doubt—a public goods experiment with sanctions under uncertainty. Journal of Empirical Legal Studies, 7(4), 847-867 (link).

- • Vernon L. Smith, 2008a. "experimental methods in economics," The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics, 2nd Edition, Abstract.

• _____, 2008b. "experimental economics," The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics, 2nd Edition. Abstract.

• Relevant subcategories are found at the Journal of Economic Literature classification codes at JEL: C9. - J. DiNardo, 2008. "natural experiments and quasi-natural experiments," The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics, 2nd Edition. Abstract.

- "Research". Duke Institute for Brain Sciences.

- Levallois, Clement; Clithero, John A.; Wouters, Paul; Smidts, Ale; Huettel, Scott A. (2012). "Translating upwards: linking the neural and social sciences via neuroeconomics". Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 13 (11): 789–797. doi:10.1038/nrn3354. ISSN 1471-003X. PMID 23034481.

- Loewenstein, G., Rick, S., & Cohen, J. (2008). Neuroeconomics. Annual Reviews. 59: 647-672. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.59.103006.093710

- Grauwe, Paul De; Ji, Yuemei (November 1, 2017). "Behavioural economics is also useful in macroeconomics".

- Bernheim, Douglas; Rangel, Antonio (2008). "Behavioural public economics".CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) in Palgrave

- "Uri Gneezy". ucsd.edu.

- "Robert Sugden".

- "Predictably Irrational". Dan Ariely. Archived from the original on 2008-03-13. Retrieved 2008-04-25.

- Staddon, John (2017). "6: Behavioral Economics". Scientific Method: How science works, fails to work or pretends to work. Routledge.

References

- Ainslie, G. (1975). "Specious Reward: A Behavioral /Theory of Impulsiveness and Impulse Control". Psychological Bulletin. 82 (4): 463–96. doi:10.1037/h0076860. PMID 1099599.

- Barberis, N.; Shleifer, A.; Vishny, R. (1998). "A Model of Investor Sentiment". Journal of Financial Economics. 49 (3): 307–43. doi:10.1016/S0304-405X(98)00027-0. Archived from the original on 20 April 2008. Retrieved 2008-04-25.

- Becker, Gary S. (1968). "Crime and Punishment: An Economic Approach" (PDF). The Journal of Political Economy. 76 (2): 169–217. doi:10.1086/259394.

- Benartzi, Shlomo; Thaler, Richard H. (1995). "Myopic Loss Aversion and the Equity Premium Puzzle" (PDF). The Quarterly Journal of Economics. 110 (1): 73–92. doi:10.2307/2118511. JSTOR 2118511.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Cunningham, Lawrence A. (2002). "Behavioral Finance and Investor Governance". Washington & Lee Law Review. 59: 767. doi:10.2139/ssrn.255778. ISSN 1942-6658.

- Daniel, K.; Hirshleifer, D.; Subrahmanyam, A. (1998). "Investor Psychology and Security Market Under- and Overreactions" (PDF). Journal of Finance. 53 (6): 1839–85. doi:10.1111/0022-1082.00077. hdl:2027.42/73431.

- Diamond, Peter; Vartiainen, Hannu (2012). Behavioral Economics and Its Applications. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-1-4008-2914-9.

- Eatwell, John; Milgate, Murray; Newman, Peter, eds. (1988). The New Palgrave: A Dictionary of Economics. Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-935859-10-2.

- Augier, Mie. Simon, Herbert A. (1916–2001).

- Bernheim, B. Douglas; Rangel, Antonio. Behavioral public economics.

- Bloomfield, Robert. Behavioral finance.

- Simon, Herbert A. Rationality, bounded.

- Genesove, David; Mayer, Christopher (March 2001). "Loss Aversion and Seller Behavior: Evidence from the Housing Market" (PDF). Quarterly Journal of Economics. 116 (4): 1233–1260. doi:10.1162/003355301753265561.

- Mullainathan, S.; Thaler, R. H. (2001). "Behavioral Economics". International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences. pp. 1094–1100. doi:10.1016/B0-08-043076-7/02247-6. ISBN 9780080430768.

- Garai, Laszlo (2016-12-01). "Identity Economics: "An Alternative Economic Psychology"". Reconsidering Identity Economics. New York: Palgrave Macmillan US. pp. 35–40. doi:10.1057/978-1-137-52561-1_3. ISBN 9781137525604.

- McGaughey, E. (2014). "Behavioural Economics and Labour Law". SSRN 2435111. Retrieved 2018-06-02.

- Hens, Thorsten; Bachmann, Kremena (2008). Behavioural Finance for Private Banking. Wiley Finance Series. ISBN 978-0-470-77999-6.

- Hogarth, R. M.; Reder, M. W. (1987). Rational Choice: The Contrast between Economics and Psychology. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-34857-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kahneman, Daniel; Tversky, Amos (1979). "Prospect Theory: An Analysis of Decision under Risk". Econometrica. 47 (2): 263–91. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.407.1910. doi:10.2307/1914185. JSTOR 1914185.

- Kahneman, Daniel; Diener, Ed (2003). Well-being: the foundations of hedonic psychology. Russell Sage Foundation.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kirkpatrick, Charles D.; Dahlquist, Julie R. (2007). Technical Analysis: The Complete Resource for Financial Market Technicians. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Financial Times Press. ISBN 978-0-13-153113-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kuran, Timur (1997). Private Truths, Public Lies: The Social Consequences of Preference Falsification. Harvard University Press. pp. 7–. ISBN 978-0-674-70758-0. Description

- Luce, R Duncan (2000). Utility of Gains and Losses: Measurement-theoretical and Experimental Approaches. Mahwah, New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Publishers. ISBN 978-0-8058-3460-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Plott, Charles R.; Smith, Vernon L. (2008). Handbook of Experimental Economics Results. 1. Elsevier. Chapter-preview links.

- Rabin, Matthew (1998). "Psychology and Economics" (PDF). Journal of Economic Literature. 36 (1): 11–46. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 27, 2011.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Shefrin, Hersh (2002). "Behavioral decision making, forecasting, game theory, and role-play" (PDF). International Journal of Forecasting. 18 (3): 375–382. doi:10.1016/S0169-2070(02)00021-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Schelling, Thomas C. (2006). Micromotives and Macrobehavior. W. W. Norton. ISBN 978-0-393-06977-8. Description

- Shleifer, Andrei (1999). Inefficient Markets: An Introduction to Behavioral Finance. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-829228-9.

- Simon, Herbert A. (1987). "Behavioral Economics". The New Palgrave: A Dictionary of Economics. 1. pp. 221–24.

- Thaler, Richard H. 2016. "Behavioral Economics: Past, Present, and Future." American Economic Review, 106 (7): 1577–1600.

- Thaler, Richard H.; Mullainathan, Sendhil (2008). "Behavioral Economics". In David R. Henderson (ed.). Concise Encyclopedia of Economics (2nd ed.). Indianapolis: Library of Economics and Liberty. ISBN 978-0-86597-665-8. OCLC 237794267.

- Wheeler, Gregory (2018). "Bounded Rationality". In Edward Zalta (ed.). Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Stanford, CA.

- "Behavioral economics in U.S. (antitrust) scholarly papers". Le Concurrentialiste.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Behavioral economics |

- The Behavioral Economics Guide

- Overview of Behavioral Finance

- The Institute of Behavioral Finance

- Stirling Behavioural Science Blog, of the Stirling Behavioural Science Centre at University of Stirling

- Society for the Advancement of Behavioural Economics

- Behavioral Economics: Past, Present, Future – Colin F. Camerer and George Loewenstein

- A History of Behavioural Finance / Economics in Published Research: 1944–1988

- MSc Behavioural Economics, MSc in Behavioural Economics at the University of Essex

- Behavioral Economics of Shipping Business