Artistic gymnastics

Artistic gymnastics is a discipline of gymnastics in which athletes perform short routines (ranging from about 30 to 90 seconds) on different apparatuses, with less time for vaulting. The sport is governed by the Fédération Internationale de Gymnastique (FIG), which designs the code of points and regulates all aspects of international elite competition. Within individual countries, gymnastics is regulated by national federations, such as Gymnastics Canada, British Gymnastics, and USA Gymnastics. Artistic gymnastics is a popular spectator sport at many competitions, including the Summer Olympic Games.

| Highest governing body | Fédération Internationale de Gymnastique |

|---|---|

| Registered players | 1881 |

| Characteristics | |

| Mixed gender | Yes |

| Type | Indoor |

| Presence | |

| Olympic | Since the first Summer Olympics in 1896 |

History

The gymnastic system was mentioned in works by ancient authors, such as Homer, Aristotle, and Plato. It included many disciplines that would later become separate sports, such as swimming, racing, wrestling, boxing, and riding,[1] and was also used for military training. In its present form, gymnastics evolved in Bohemia and what is now (Germany) at the beginning of the 19th century, and the term "artistic gymnastics" was introduced at the same time to distinguish free styles from the ones used by the military.[2] The German educator Friedrich Ludwig Jahn, who was known as the father of gymnastics,[3] invented several apparatus, including the horizontal bar and parallel bars, which are used to this day.[4] Two of the first gymnastics clubs were Turnvereins and Sokols.

In 1881, the FIG was founded, and it remains the governing body of international gymnastics. It initially included only three countries and was called the European Gymnastics Federation until 1921, when the first non-European countries joined the federation and it was reorganized into its present form. Gymnastics was included in the program of the 1896 Summer Olympics, but women have been allowed to participate in the Olympics only since 1928. The World Championships, held since 1903, were open only to men until 1934. Since that time, two branches of artistic gymnastics have developed: women's artistic gymnastics (WAG) and men's artistic gymnastics (MAG). Unlike men's and women's branches of many other sports, WAG and MAG differ significantly in apparatus used at major competitions and in techniques.

Women's artistic gymnastics (WAG)

Women's gymnastics entered the Olympics as a team event in 1928 and was included in the 12th gymnastics world championships in 1950. Individual women were recognized in the all-around as early as the tenth world championships in 1934. Two years after the full women's program (all-around and all four event finals) was introduced at the 1950 World Championships, it was added to the 1952 Summer Olympics in Helsinki, Finland, and the format has remained to this day.

The earliest champions in women's gymnastics tended to be in their 20s, and most had studied ballet for years before entering the sport. Larisa Latynina, the first great Soviet gymnast, won her first Olympic all-around medal at age 22 and second at 26; she became world champion in 1958 while pregnant with her daughter. Věra Čáslavská of Czechoslovakia, who followed Latynina to become a two-time Olympic all-around champion, was 22 before she started winning gold medals.

In the 1970s, the average age of Olympic gymnasts began to decrease. While it was not unheard-of for teenagers to compete in the 1960s—Ludmilla Tourischeva was 16 at her first Olympics in 1968—younger female gymnasts slowly became the norm as the sport's difficulty increased. Smaller, lighter girls generally excelled in the more challenging acrobatic elements required by the redesigned Code of Points. The 58th Congress of the FIG—held in July 1980, just before the Olympics—decided to raise the minimum age for senior international competition from 14 to 15.[5] The change, which came into effect two years later, did not eliminate the problem. By the time of the 1992 Summer Olympics, elite competitors consisted almost exclusively of "pixies"—underweight, prepubertal teenagers—and concerns were raised about athletes' welfare.

The FIG responded to this trend by raising the minimum age for international elite competition to 16 in 1997. This, combined with changes in the Code of Points and evolving popular opinion in the sport, led to the return of older gymnasts. While the average elite female gymnast is still in her middle to late teens and of below-average height and weight, it is also common to see gymnasts competing well into their 20s. At the 2004 Olympics, both the second-place American team and the third-place Russians were captained by women in their mid-20s; several other teams, including Australia, France, and Canada, included older gymnasts. At the 2008 Olympics, the silver medalist on vault, Oksana Chusovitina, was a 33-year-old mother. She received another silver medal on vault at the 2011 World Championships in Tokyo, when she was 36. At the age of 41, Chusovitina competed at her 7th consecutive Olympics at the 2016 Olympics, a world record for gymnastics.

Apparatus

Both male and female gymnasts are judged on all events for execution, degree of difficulty, and overall presentation skills. In many competitions, especially high-level ones sanctioned by the FIG, such as the World Championships or Olympics, gymnasts compete in Olympic Order, which has changed over time, but has stayed consistent now for at least a few decades.

Men and women

- Vault

- The vault is an event as well as the primary piece of equipment used in that event. Unlike most of the gymnastic events employing apparatuses, the vault is common to both men's and women's competition, with little difference between the two categories. A gymnast sprints down a runway, which is a maximum of 25 m (82 ft) in length, before leaping onto a springboard. Harnessing the energy of the spring, the gymnast directs his or her body hands-first towards the vault. Body position is maintained while "popping" (blocking using only a shoulder movement) the vaulting platform. The gymnast then rotates his or her body so as to land in a standing position on the far side of the vault. In advanced gymnastics, multiple twists and somersaults may be added before landing. Successful vaults depend on the speed of the run, the length of the hurdle, the power the gymnast generates from the legs and shoulder girdle, kinesthetic awareness in the air, and the speed of rotation in the case of more difficult and complex vaults.

- In 2001, the traditional vaulting horse was replaced with a new apparatus, sometimes known as a tongue or table. It is more stable, wider, and longer than the older vaulting horse—approximately 1 m (3.3 ft) in length and width—giving gymnasts a larger blocking surface, and is therefore safer than the old vaulting horse. With the addition of this new and safer apparatus, gymnasts are attempting more difficult and dangerous vaults.

- Floor exercise

- The floor event occurs on a carpeted 12 m × 12 m (39 ft × 39 ft) square, called a "spring floor", consisting of hard foam over a layer of plywood, which is supported by springs or foam blocks. This provides a firm surface that will respond with force when compressed, allowing gymnasts to achieve extra height and a softer landing than would be possible on a regular floor. A series of tumbling passes are performed to demonstrate flexibility, strength, balance, and power. The gymnast must also show non-acrobatic skills, including circles, scales, and press handstands. Men's floor routines usually have multiple passes that will total from 60 to 70 seconds, and men perform without music (unlike women gymnasts). Rules require that gymnasts touch each corner of the floor at least once during their routine. Female gymnasts perform a 90-second choreographed routine to instrumental music on the same spring floor used by male gymnasts. Female routines consist of tumbling passes, a series of jumps, several dance elements, acrobatic skill elements, and turns. Elite gymnasts may perform up to four tumbling passes, each of which includes three or more skills.

Men only

- Pommel horse

- A typical pommel horse exercise involves both single leg and double leg work. Single leg skills are generally found in the form of scissors, an element often done on the pommels. Double leg work however, is the main staple of this event. The gymnast swings both legs in a circular motion (clockwise or counterclockwise depending on preference) and performs such skills on all parts of the apparatus. To make the exercise more challenging, gymnasts will often include variations on a typical circling skill by turning (moores and spindles) or by straddling their legs (flairs). Routines end when the gymnast performs a dismount, either by swinging his body over the horse, or landing after a handstand.

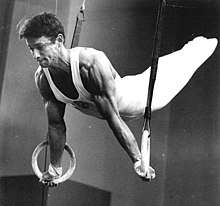

- Still rings

- The still rings are suspended on wire cable from a point 5.8 m (19 ft) off the floor[6] and adjusted in height so the gymnast has room to hang freely and swing. He must perform a routine demonstrating balance, strength, power, and dynamic motion while preventing the rings themselves from swinging. At least one static strength move is required, but some gymnasts may include two or three. Most routines begin with a difficult mount and conclude with a difficult dismount.

- Parallel bars

- Men perform on two bars slightly further than a shoulder's width apart and usually 1.75 m (5.7 ft) high while executing a series of swings, balances, and releases that require great strength and coordination.

- Horizontal or high bar

- A 2.4 cm (0.94 in) thick steel bar raised 2.5 m (8.2 ft) above the landing area is all the gymnast has to hold onto as he performs giants (revolutions around the bar), release skills, twists, and changes of direction. By using the momentum from giants, enough height can be achieved for spectacular dismounts, such as a triple-back salto. Leather grips are usually used, to help maintain a grip on the bar.

Women only

- Uneven bars

The Uneven Parallel Bars were adapted, by the Czechoslovakian Sokol from the men's Parallel Bars some time before World War I and were shown in international exphibition for the first time at the 1928 Amsterdam Summer Olympic Games.[7].

On the uneven bars (also known as asymmetric bars in the UK), the gymnast navigates two horizontal bars set at different preset heights yet alterable widths. Gymnasts perform swinging, circling, transitional and release moves as well as moves that pass through handstand. The most common way to mount these bars is by jumping toward the lower bar first.

Higher-level gymnasts usually wear leather grips to ensure a grip is maintained on the bars while protecting hands from painful blisters and tears (known as rips). Gymnasts sometimes wet their grips with water from a spray bottle and then may apply chalk to their grips to prevent the hands from slipping. Chalk may also be applied to the hands and bar if grips are not worn.

- Balance beam

The balance beam, as an apparatus, has existed as a piece of gymnastics equipment at least as far back as the time since Miroslav Tyrš (hence, at least as far back as the 1880s), in its form of "low beam" close to the floor.[8] By no later than the 1920s, the beam was raised to a much greater height, and this innovation is a credit to the Swedish influence on the sport.[9]

The gymnast performs a choreographed routine from 70 to 90 seconds in length, consisting of leaps, acrobatic skills, turns and dance elements on a padded spring beam. Apparatus norms set by the International Gymnastics Federation (used for Olympic and most elite competitions) specify the beam must be 125 cm (4 ft) high, 500 cm (16 ft) long, and 10 cm (3.9 in) wide.[10] The event requires balance, flexibility and strength.

Competition format

Currently, in Olympic or World Championships competition, the meet is divided into several sessions that are held on different days: qualification, team finals, all-around finals, and event finals.

During the qualification (abbreviated TQ) round, gymnasts compete with their national squad on all four (WAG) or six (MAG) apparatus. The scores from this session are not used to award medals, but are used to determine which teams advance to the team finals and which individual gymnasts advance to the all-around and event finals. For the 2020 Olympic cycle a new qualification format has been adopted. Each country can enter six gymnasts: a four-person team and two individual gymnasts. The current format of team qualification is 4–4–3, meaning that there are four gymnasts on the team, all four compete on each event, and three of the scores count. Individual gymnasts also compete to be qualified to the all-around and event finals, but their scores do not count toward team score.

In the team finals (abbreviated TF), gymnasts compete with their national squad on all four/six apparatus. The scores from the session are used to determine the medalists of the team competition. The current format is 4–3–3, meaning that there are four gymnasts on the team, three compete on each event, and all three scores count.[11]

In the all-around finals (abbreviated AA), the gymnasts are individual competitors and perform on all four/six apparatus. Their scores from all four/six events are added together and the gymnasts with the three highest totals are awarded all-around medals. Only two gymnasts from each country may advance to the all-around finals.

In the event finals (abbreviated EF) or apparatus finals, the top eight gymnasts on each event compete for medals. Only two gymnasts from each country may advance to each event final.

Other competitions are not bound by these rules, and may use other formats. For instance, the 2007 Pan American Games had only one day of team competition on a 6–5–4 format, and allowed three athletes from each country to advance to the all-around. In other meets, such as those on the World Cup circuit, the team event is not contested at all.

New life

Competitions use the New Life scoring rule, which was introduced in 1989. Under New Life, marks from one session do not carry over to the next. In other words, a gymnast's performance in team finals does not affect his or her scores in the all-around finals or event finals; he or she starts with a clean slate. In addition, the marks from the team qualifying round do not count toward the team finals.

Before the introduction of the New Life rule, the scores from the team competition carried over into the all-around and event finals, and could have a negative or positive effect on the gymnast's efforts in subsequent sessions. The gymnasts' final results, and medal placement were previously determined by the combination of the following scores:

- Qualifiers for all-around and event finals

- Team compulsories + team optionals

- Team competition

- Team compulsories + team optionals[12]

- All-around competition

- Team results (compulsories and optionals) averaged + all-around

- Event finals

- Team results (compulsories and optionals) averaged + event final

Compulsories

Before 1997, team competition was structured differently. It still consisted of two sessions, but gymnasts performed compulsory exercises in the preliminaries and their own optional routines on the second day. The team medals were awarded based on the combined scores of both days. All-around and event final qualifiers were determined according to the combined scores. In meets where team titles were not contested, such as the American Cup, there were two days of all-around competition: one for compulsories and another for optionals.

The optionals were the gymnasts' personal routines, developed with their coaches to adhere to the requirements of the Code of Points. They were performed in the team finals, the all-around and the event finals.

The compulsories were routines that were developed and choreographed by the FIG Technical Committee. They were performed on the first day of the team competition. Every single elite gymnast in every FIG member nation performed the same exercises. The dance and tumbling skills of compulsory routines were generally less difficult than those of optionals, but heavily emphasized perfect technique, form and execution. Scoring was exacting with judges taking deductions for even slight deviations from the required choreography. For this reason, many gymnasts and coaches considered compulsories more challenging to execute than optionals.

Compulsories were eliminated at the end of 1996. The move was extremely controversial, and many successful gymnastics federations, including the United States, Russia and China, voted against the abolition of compulsories. They argued that the exercises helped maintain a high standard of form, technique and execution among gymnasts. Opponents believed that compulsories harmed emerging gymnastics programs. Many members of the gymnastics community still argue that compulsories should be reinstated.

Many gymnastics federations have maintained compulsories in their national programs. Gymnasts competing at the lower levels of the sport—for instance, Level 4–6 in USA Gymnastics, grade 2 in South Africa and national levels 3–6 in Australia—frequently only perform compulsory routines.

Competition levels

Artistic gymnasts compete only with other gymnasts in their level. Gymnasts start at the lowest level of competition and advance to higher levels by learning gymnastics skills and achieving qualifying scores at competitions.

In America, levels range from 1 to 10, then junior elite and senior elite. Elite, especially senior elite is considered Olympic level, and these gymnasts generally perform routines designed to meet the FIG's Code of Points. Levels 1–2 are usually considered recreational, or beginner; 3–6 intermediate, and 7–Elite advanced. Competitions begin at level 3, and in some gyms, level 2. A gymnast must have specific skills for each event in order to advance to the next level, and once a gymnast has competed in a Sectional meet, they may not drop back to a lower level in the same competitive season. Levels 1–2 are basic skills such as handstands, cartwheels etc. 3–5 are compulsory levels, and 6 is an in-between level with strict requirements but still allowing the gymnast to contribute their own creativity.

In the UK, the levels system goes from 5 (lowest) to 2, and there are two tracks for elite- and club-level competition. In Canada there are several different competitive streams: recreational, developmental, pre-competitive, provincial, national, and high performance. Provincial levels range from 5 (lowest) to 1; national levels are pre-novice, novice, open, and high performance. High performance levels are novice, junior, and senior.

In Germany, there are different competitive systems for grassroots sport and for high-performance sport. For hobby sportsmen there is a system of compulsory exercises from 1 to 9 and optional exercises from 4 to 1 with modified requirements of the code of points. This competitions end on national level. For high-performance and junior athletes there are several compulsory and optional requirements, defined by age (age class exercises) from age 6 to 18.[13]

Age limits

The FIG imposes a minimum age limit on gymnasts competing in international meets. The term senior, in gymnastics, refers to any world-class or elite gymnast who is age-eligible under FIG rules. The term junior refers to any gymnast who competes at a world-class or elite level, but is too young to be classified as a senior. Currently, female gymnasts must be at least sixteen years of age, or turning sixteen within the calendar year, the male 18, to be classified as a senior. Juniors are judged under the same Code of Points as the seniors, but with further restrictions, and often exhibit the same level of difficulty in their routines.

Many meets, such as the European Championships, have separate divisions for juniors, but some competitions, such as the Goodwill Games, the Pan Am Games, the Pacific Rim Championships and the All-Africa Games, have rules that permit seniors and juniors to compete together.

Only senior gymnasts are allowed to compete in the Olympics, World Championships and World Cup circuit. For the current Olympic cycle, in order to compete in the 2016 Olympics, a female gymnast must have a birthdate before 1 January 2001 (corresponding to an age of at least 15 years and 8 months on the first day of the games), the counterpart gender must be minimum 18 years old. There is no maximum age restriction.

The minimum age requirement is arguably one of the most contentious rules in artistic gymnastics, and frequently debated by coaches, gymnasts and other members of the gymnastics community. Those in favor of the age limits argue that they promote the participation of older athletes in the sport, and spare younger gymnasts from the stress of competition and training at a high level. Opponents of the rule point out that junior gymnasts are scored under the same Code of Points as the seniors except with some restrictions, and juniors train mostly the same skills. They also feel that younger gymnasts need the experience of participating in major events in order to compete better as athletes, and if a junior has the skills and maturity to be competitive with seniors, he or she should be allowed that opportunity.

Another point that frequently arises in this debate is the issue of age falsification. Since stricter age limit rules were first adopted in the early 1980s, there have been several well-documented, and many more suspected, cases of juniors with falsified documents competing as seniors. The FIG has only taken disciplinary action in three cases: those of Kim Gwang-Suk of North Korea, who competed at the 1989 World Artistic Gymnastics Championships at the approximate age of eleven; North Korean Hong Su-jong, who competed under three different birth dates in the 2000s, and China's Dong Fangxiao, who competed at the 2000 Olympics when she was two years below the age minimum.

While the minimum age requirement applies to both women and men, it is far more contentious in the women's program. Most top male gymnasts are in their late teens or early twenties, while female gymnasts are typically ready to compete at the international level by their mid-teens. The difference is largely due to the fact that the men's skills tend to emphasize strength more than the women's skills.

Scoring and the Code of Points

Scoring at the international level is regulated by the code of points. This system was significantly overhauled for 2006. Under the new code of points, there are two different panels judging each routine, evaluating different aspects of the performance. The D score covers difficulty value, element group requirements, and connection value; the E score covers execution, composition and artistry. The most visible change to the code was the abandonment of the "perfect 10" for an open-ended scoring system for difficulty (the D score). The E score is still limited to a maximum of 10. The sum of the two provides a gymnast's total score for the routine. Theoretically this means scores could be infinite, although average marks for routines in major competitions in 2016 generally stayed in the mid-teens.

Many gymnasts, including Nadia Comăneci, Mary Lou Retton, Josef Stalder, and Kurt Thomas, have attributed their original skills to the table of elements section of the code that helps define a routine's difficulty.

Before 2006, every routine was assigned a Start Value (SV). A routine performed perfectly with maximum SV was 10.0. A routine with all required elements was automatically given a base SV (9.4 in 1996; 9.0 in 1997; 8.8 in 2001). It was up to the gymnast to increase the SV to 10.0 by performing harder skills and combinations.

Gymnasts, coaches, officials are among many who have protested the new code, with Olympic gold medalists Lilia Podkopayeva, Svetlana Boguinskaya, Shannon Miller and Vitaly Scherbo and Romanian team coach Nicolae Forminte publicly voicing their opposition. In addition, the 2006 report from the FIG Athletes' Commission cited major concerns about scoring, judging and other points of the new Code. Aspects of the code were revised in 2007; but there are no plans to abandon the new scoring system and return to the 10.0 format.

Major competitions

Global

- Olympic Games: Artistic gymnastics is one of the most popular events at the Summer Olympics, held every four years. Gymnastics teams qualify for the Olympics based on their performance at the World Championships the year before the Games. Nations that do not qualify to send a full team may qualify to send one or two individual gymnasts.

- World Championships: The gymnastics-only World Championships is open to teams from every FIG-member nation. The competition has had several different formats, depending on the year: full team finals, all-around, and event finals; all-around and event finals only; or event finals only. Since 2019, Junior World Championships are held every two years.

- Artistic Gymnastics World Cup and World Challenge Cup Series

- Goodwill Games: Artistic gymnastics was an event at this now-defunct competition.

Regional

- All-Africa Games: Gymnastics is one of the events in this multi-sport competition, held every four years, and open to teams and gymnasts from African nations.

- Asian Games: Artistic gymnastics is one of the events in this multi-sport competition, held every four years, and open to teams and gymnasts from Asian nations.

- Commonwealth Games: Artistic gymnastics is one of the events in this multi-sport competition, held every four years, and open to teams and gymnasts from Commonwealth nations.

- European Championships: The gymnastics-only European Championships is held every year, and is open to teams and gymnasts from European nations.

- Pacific Rim Championships: This gymnastics-only competition, which was known as the Pacific Alliance Championships until 2008, is held every two years and is open to teams from members of the Pacific Alliance of National Gymnastics Federations, including the US, China, Australia, Canada, Mexico, New Zealand and other nations on the Pacific coast.

- Pan American Games: Gymnastics is one of the events in this multi-sport competition, held every four years, and open to teams and gymnasts from North, South and Central America.

- South American Games: Artistic gymnastics is one of the events in this multi-sport competition, held every four years, and open to teams and gymnasts from South American nations.

National

Most countries hold a major competition (National Championships, or "Nationals") every year that determines the best-performing all-around gymnasts and event specialists in their country. Gymnasts may also qualify to their country's national team or be selected for international meets based on their scores at Nationals.

Dominant teams and nations

USSR and post-Soviet republics

Before the breakup of the Soviet Union in 1991, Soviet gymnasts dominated both men's and women's gymnastics, commencing with the introduction of the full women's program into the Olympics and the overall increased standardization of the Olympic gymnastics competition format which happened in 1952. Soviet Union's success might be explained by a heavy state's investment in sports to fulfil its political agenda on an international stage.[14] They had many male stars, such as Olympic all-around champions Viktor Chukarin and Vitaly Scherbo, and female stars, such as Olympic all-around champion Larisa Latynina and World all-around and Olympic champion Svetlana Boginskaya who contributed to this tradition. From 1952 to 1992 inclusive, the Soviet women's squad won almost every single team title in World Championship competition and at the Summer Olympics: the only four exceptions were the 1984 Olympics, which they did not attend, and the 1966, 1979, and 1987 World Championships. Most of the famous Soviet gymnasts were from the Russian SFSR, the Ukrainian SSR and the Byelorussian SSR.

Following the breakup of the Soviet Union, they competed together as one nation for the last time at the 1992 Summer Olympics as the Unified Team, winning the gold. Russia has maintained the tradition of gymnastics excellence, medaling at every Worlds and Olympic competition in both MAG and WAG disciplines, except in the 2008 Olympics, where the Russian women's team did not win any medals. Ukraine also has a strong team; Ukrainian Lilia Podkopayeva was the all-around champion at the 1996 Olympics. Belarus has maintained a strong men's team. Other former republics have been somewhat less successful. In terms of medal results and overall domination, the Soviet legacy remains the strongest of all in artistic gymnastics.

Romania

The Romanian team first achieved wide-scale success at the 1976 Summer Olympics with the tremendous performance of Nadia Comăneci. Since then, using the centralized training system pioneered by Béla Károlyi, they have been a dominant force in both team and individual events in WAG. With the exception of the defeat of the Soviet women's team by the Czechoslovakian women's team at the 1966 World Championships, Romania was the only team ever to defeat the Soviets in head-to-head competition at the World Championships/Olympic level with their victories at the 1979 and 1987 Worlds. Their women's teams have also won team medals at every Olympics from 1976 to 2012 inclusive, including three victories in 1984, 2000, and 2004. At the 16 World Championships from 1978 to 2007 inclusive, the women's team failed to medal only twice (in 1981 and 2006) and has won the team title seven times, including five victories in a row (1994–2001). From 1976 to 2000, they placed notable gymnasts such as Daniela Silivaş, Lavinia Miloşovici, and Simona Amânar on the Olympic all-around podium at every Olympics, and have usually done the same for the individual events at the World Championships through 2015, producing World all-around champions Aurelia Dobre and Maria Olaru. The Romanian men's program, while less successful, is still maturing and producing individual medalists such as Marian Drăgulescu and Marius Urzică at World and Olympic competitions, and they have started winning team medals as well. The Romanian women's team failed to qualify for the 2016 Summer Olympics, but they sent 3-time Olympic champion, Cătălina Ponor, to represent Romania.

United States

While isolated American gymnasts, including Kurt Thomas and Cathy Rigby, won medals in World Championship meets in the 1970s, the United States team was largely considered a "second power" until the mid- to late 1980s, when American gymnasts began medaling consistently in major, fully attended competitions. In 1984, the Olympic men's team won the gold. The team included Tim Daggett, Peter Vidmar, Mitch Gaylord, Bart Conner, Scott Johnson, Jim Hartung, and the team alternate Jim Mikus. Also in 1984, Mary Lou Retton became the first American Olympic all-around champion and won individual medals as well. In 1991, Kim Zmeskal became the first American world all-around champion. At the 1992 Olympics, the American women won their first team medal (bronze), as well as their highest all-around ranking, a silver medal by Shannon Miller, in a fully attended Games. In men's gymnastics, Trent Dimas was able to capture the gold medal on the horizontal bar. This was the second time that an American gymnast, male or female, won a gold medal in an Olympics held outside the United States. The U.S. women's team has become increasingly successful in the modern era, with the 1996 Olympic team victory of the Magnificent Seven in Atlanta, the 2003 Worlds team victory in Anaheim, California, and multiple-medal hauls in both WAG and MAG at the 2004 Olympics. At the 2012 Olympics and 2016 Olympics, the U.S. women won the team gold. The United States has produced individual gymnasts such as Olympic all-around champions Carly Patterson (2004), Nastia Liukin (2008), Gabby Douglas (2012), and Simone Biles (2016), and world all-around champions Kim Zmeskal (1991), Shannon Miller (1993, 1994), Chellsie Memmel (2005), Shawn Johnson (2007), Bridget Sloan (2009), Jordyn Wieber (2011), Simone Biles (2013, 2014, 2015, 2018, 2019), and Morgan Hurd (2017). Of particular note is that at the 2005 World Championships in Melbourne, American women won the gold and silver the all-around and went 1–2 in every single event final except vault (in which they placed third). They continue to be one of the most dominant forces in the sport. The men's team has also matured, making the medal podium at both the 2004 and 2008 Olympics; they also made the podium at the 2003 and 2011 World Championships. Paul Hamm, the most successful U.S. male gymnast, became the first American to win the world all-around title in 2003. He followed this up by winning the gold medal at the 2004 Olympic Games. 2010 world all-around bronze medalist Jonathan Horton captured the silver medal on the horizontal bar at the 2008 Olympic Games, and Danell Leyva won the all-around bronze medal at the 2012 Olympic Games, as well as two silver medals (parallel bars and high bar) at the 2016 Olympic Games.

China

China has developed strong, successful programs in both WAG and MAG over the past 25 years, earning both team and individual medals. The Chinese men won team gold at the 2000 and 2008 Olympics, and every team world championship since 1994, except 2001 when they placed fifth. They have produced individual gymnasts like Olympic (and world) all-around champions Li Xiaoshuang (1996) and Yang Wei (2008). The Chinese women's team won team gold at the 2006 World Championships and 2008 Olympics, and has produced individual gymnasts like Olympic, world and World Cup champions like Mo Huilan, Kui Yuanyuan, Yang Bo, Ma Yanhong, Cheng Fei, Sui Lu, Huang Huidan, Yao Jinnan and Fan Yilin. Chinese female Olympic individual gold medalists include Ma Yanhong, Lu Li, Liu Xuan, He Kexin and Deng Linlin. Though for many years considered a two-event team (uneven bars and balance beam), they have developed and continue to develop successful all-arounders like Olympic all-around bronze medalists Liu Xuan, Zhang Nan and Yang Yilin, but like the former USSR, they have been plagued in western media with reports of their grueling and sometimes cruel training methods including age falsification accusations.

Japan

Japan was largely dominant in MAG during the 1960s and 1970s, winning every Olympic team title from 1960 through 1976 thanks to individual gymnasts such as Olympic all-around champions Sawao Kato and Yukio Endo. Several innovations pioneered by Japanese gymnasts during this era have remained in the sport, including the Tsukahara vault. Japanese male gymnasts have re-emerged as a team to reckon with since winning a team gold at the 2004 Olympics. Six-time world champion and Two-time Olympic All-around gold medalist Kohei Uchimura is widely considered to be the best all-around gymnast ever. The women have been less successful, but there have been such standouts as Olympic and world medalist Keiko Tanaka Ikeda, who competed in the 1950s and 1960s. There have also been some emerging talents in recent years, such as Koko Tsurumi, Rie Tanaka, Yuka Tomita, Natsumi Sasada, Yuko Shintake, Asuka Teramoto, Sae Miyakawa, Hitomi Hatakeda, Aiko Sugihara and Mai Murakami who did provide the women's team with talent worthy of placing in the top teams at the last championships and Olympics. They also have been winning world individual medals, Tsurumi's all-around bronze and bars silver at 2009 and Murakami's floor gold at 2017, the first Japanese gold since Keiko Tanaka.

Germany

The German Democratic Republic, or East Germany, had an extremely successful gymnastics program before the reunification of Germany. Both the MAG and WAG teams frequently won silver or bronze team medals at the World Championships and Olympics. Male gymnasts such as Andreas Wecker and Roland Brückner and female gymnasts such as Maxi Gnauck and Karin Janz contributed to their country's success. The Federal Republic of Germany had international stars, too, like Eberhard Gienger, Willi Jaschek or Helmut Bantz. Since the reunification of Germany, they have continued to achieve great results and win world and Olympic medals with gymnasts as Fabian Hambüchen, Philipp Boy, and Marcel Nguyen among the men, and Pauline Schäfer, Elizabeth Seitz, Sophie Scheder and Tabea Alt among the women. The former Soviet/Uzbek gymnast Oksana Chusovitina also competed for Germany during some years, winning two world medals and an Olympic silver on vault.

Czechoslovakia

The Czechoslovakian women's team had a very long tradition of success and was the chief threat to the dominance of the Soviet women's team for decades. They won team medals at every World Championships and Olympics from 1934 to 1970, with the exceptions of the 1950 Worlds and 1956 Olympics. Among their leaders were the first women's world all-around champion, Vlasta Děkanová (1934, 1938) and Věra Čáslavská, who won outright all five European, World and Olympic all-around titles during an Olympic cycle from 1964 to 1968—a feat never matched by any other gymnast, male or female. Čáslavská also led her teammates to the world team title in 1966, making the Czechoslovakians one of two national teams (Romania being the other) ever to defeat the Soviet women's team at a major competition. Their men's success came earlier and was concurrent with the success of Dekanova, but by the time of Caslavska, they had no significant male counterparts among the men for their women. Their overall success, however, at the World Artistic Gymnastics Championships was the greatest of any country prior to World War II in terms of being first in the medal table more than any other country and winning the most team titles of any team during the pre-WWII period. Also, as Czechoslovakia, or in their pre World War I nationhood as the Austro-Hungarian constituent Bohemia, they produced 4 different Men's World All Around Champions: Josef Cada in 1907, Ferdinand Steiner in 1911, Frantisek Pechacek in 1922, and Jan Gajdos in 1938. Perhaps their most decorated athlete, overall, was Ladislav Vacha who won a total of 10 individual medals at the Olympics and World Championships – moreso than any other of their athletes.

Hungary

Another Eastern Bloc country whose women achieved notable results was Hungary. Led by individuals such as 10-time Olympic medalist (with five golds) Ágnes Keleti, their team medaled at the first four Olympics with women's artistic gymnastics competitions (1936–1956), as well as at the 1954 World Championships. Their women's program went into a decline with minor occasional success, although much later, during the late 1980s and early 1990s, world and Olympic Vault champion Henrietta Ónodi put them back on the map. Their men never had quite the same level of success as their women, although Zoltán Magyar dominated the pommel horse event during the 1970s, winning eight (of a possible nine) European, World and Olympic titles from 1973 to 1980. World and Olympic champion on rings, Szilveszter Csollány, also kept Hungary on the medal platform at major competitions for a decade starting in the early 1990s. In more recent years, Krisztián Berki has won World and Olympic titles on the Pommel Horse.

Other nations

Several other nations were at one time or have become in recent years serious contenders in both WAG and MAG. Part of the rise of the success of various countries' programs in recent years is attributable to the exodus of lots of talent from the USSR and other former Eastern Bloc countries. South Korea, Canada, Australia, Brazil, Netherlands, France, Italy and Great Britain are among the other countries to have produced world and Olympic medalists and have started winning team medals at continental, world and Olympic level. Individual gymnasts from Spain, Greece, Hungary, North Korea, Croatia and Slovenia have also achieved notorious results in major competitions.

Health effects

Artistic gymnastics carries inherently high risk of spinal and other injuries.[15][16] Eating disorders can also be quite common, especially in women's gymnastics when gymnasts are motivated and sometimes pushed by coaches to maintain a lower than normal bodyweight.

See also

- List of current female artistic gymnasts

- List of notable artistic gymnasts

- International Gymnastics Hall of Fame

- List of Olympic medalists in gymnastics (men)

- List of Olympic medalists in gymnastics (women)

- Artistic Gymnastics terms named after people

References

- "Sportivnaya gimnastika". Enciklopediya Krugosvet (in Russian). Archived from the original on 20 June 2008. Retrieved 11 April 2006.

- "Artistic Gymnastics – History". IOC. Retrieved 11 April 2006.

- "Gymnastics". Encarta. Archived from the original on 18 September 2009. Retrieved 11 April 2006.

- "A History of Gymnastics: From Ancient Greece to Modern Times | Scholastic". www.scholastic.com. Retrieved 30 May 2017.

- "Within the International Federations" (PDF). Olympic Review (155): 520. September 1980. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 May 2006. Retrieved 11 April 2006.

- "Apparatus Norms". FIG. p. II/18. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 December 2011. Retrieved 16 November 2009.

- Dusek, Peter Paul Jr. (1981). Marie Provaznik: Her Life and Contributions to Physical Education. University of Utah. p. 350.

- Dusek, Peter Paul Jr. (1981). Marie Provaznik: Her Life and Contributions to Physical Education. University of Utah. p. 349.

- Dusek, Peter Paul Jr. (1981). Marie Provaznik: Her Life and Contributions to Physical Education. University of Utah. p. 349.

- Apparatus Norms, International Gymnastics Federation, p.63. Retrieved 27 March 2007.

- "Q and A on the new Olympic qualification system in Gymnastics", FIG, 21 May 2015

- Mitchell, sarai. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help); Missing or empty|title=(help) - "Kari Wertungsvorschriften Gerätturnen Frauen und Männer". Judge Homepage of the German Gymnastics Association (DTB). Deutscher Turner-Bund e. V. Retrieved 7 October 2016.

- "The Role of Sports in The Soviet Union | Guided History".

- Sands, William (2015). "Stretching the Spines of Gymnasts: A Review". Sports Medicine (Auckland, N.z.). 46 (3): 315–327. doi:10.1007/s40279-015-0424-6. PMC 4769315. PMID 26581832.

- Kruse, David. "Spine Injuries in the Sport of Gymnastics" (PDF).

External links