Antonio López de Santa Anna

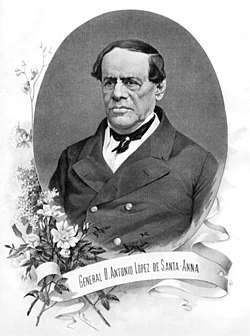

Antonio de Padua María Severino López de Santa Anna y Pérez de Lebrón (Spanish pronunciation: [anˈtonjo ˈlopes ðe sant(a)ˈanna]; 21 February 1794 – 21 June 1876),[1] usually known as Santa Anna[2] or López de Santa Anna, was a Mexican politician and general. His influence on post-independence Mexican politics and government in the first half of the nineteenth century is such that historians often refer to it as the "Age of Santa Anna."[3] He was called "the Man of Destiny" who "loomed over his time like a melodramatic colossus, the uncrowned monarch."[4] Santa Anna's military and political career was a series of reversals. He first opposed Mexican independence from Spain, but then fought in support of it. He backed the monarchy of Mexican Empire, then revolted against the emperor. He "represents the stereotypical caudillo in Mexican history".[5][6] Lucas Alamán wrote that "the history of Mexico since 1822 might accurately be called the history of Santa Anna's revolutions. His name plays a major role in all the political events of the country and its destiny has become intertwined with his."[7]

Antonio López de Santa Anna | |

|---|---|

| |

| 8th President of Mexico | |

| In office 20 April 1853 – 9 August 1855 | |

| Preceded by | Manuel María Lombardini |

| Succeeded by | Martín Carrera |

| In office 20 May 1847 – 15 September 1847 | |

| Preceded by | Pedro María de Anaya |

| Succeeded by | Manuel de la Peña y Peña |

| In office 21 March 1847 – 2 April 1847 | |

| Preceded by | Valentín Gómez Farías |

| Succeeded by | Pedro María de Anaya |

| President of the Mexican Republic | |

| In office 4 June 1844 – 12 September 1844 | |

| Preceded by | Valentín Canalizo |

| Succeeded by | José Joaquín de Herrera |

| In office 4 March 1843 – 8 November 1843 | |

| Preceded by | Nicolás Bravo |

| Succeeded by | Valentín Canalizo |

| In office 10 October 1841 – 26 October 1842 | |

| Preceded by | Francisco Javier Echeverría |

| Succeeded by | Nicolás Bravo |

| In office 20 March 1839 – 10 July 1839 | |

| Preceded by | Anastasio Bustamante |

| Succeeded by | Nicolás Bravo |

| President of the United Mexican States | |

| In office 24 April 1834 – 27 January 1835 | |

| Preceded by | Valentín Gómez Farías |

| Succeeded by | Miguel Barragán |

| In office 27 October 1833 – 15 December 1833 | |

| Preceded by | Valentín Gómez Farías |

| Succeeded by | Valentín Gómez Farías |

| In office 18 June 1833 – 5 July 1833 | |

| Preceded by | Valentin Gómez Farías |

| Succeeded by | Valentín Gómez Farías |

| In office 17 May 1833 – 4 June 1833 | |

| Preceded by | Valentín Gómez Farías |

| Succeeded by | Valentín Gómez Farías |

| Vice President of the Mexican Republic | |

| In office 16 April 1837 – 17 March 1839 | |

| President | Anastasio Bustamante |

| Preceded by | Valentin Gomez Farias |

| Succeeded by | Nicolas Bravo |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 21 February 1794 Xalapa, Veracruz, Viceroyalty of New Spain (now Mexico) |

| Died | 21 June 1876 (aged 82) Mexico City, Mexico |

| Resting place | Panteón del Tepeyac, Mexico City |

| Political party | Liberal |

| Spouse(s) | María Inés de la Paz García (m. 1825; died 1844) María de los Dolores de Tosta (m. 1844) |

| Awards | |

| Signature |  |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Years of service | 1810–1855 |

| Rank | General |

Santa Anna was an enigmatic, patriotic, and controversial figure who had great power in Mexico during a turbulent 40-year career. He led as general at crucial points and served 12 non-consecutive presidential terms over a period of 22 years.[lower-alpha 1] In the periods of time when he was not serving as president, he continued to pursue his military career.[9] He was a wealthy landowner who built a political base in the port city of Veracruz. He was perceived as a hero by his troops, as he sought glory for himself and his army and independence for Mexico. He repeatedly rebuilt his reputation after major losses. Yet at the same time, historians and many Mexicans also rank him as one of "those who failed the nation."[10] His centralist rhetoric and military failures resulted in Mexico losing half its territory, beginning with the Texas Revolution of 1836 and culminating with the Mexican Cession of 1848 following its loss to the United States in the Mexican–American War. But his leadership in the Mexican-American War and his willingness to fight to the bitter end prolonged the war. "More than any other single person it was Santa Anna who denied Polk's dream of a short war."[11] After the debacle of the war, he returned to the presidency and in 1853 sold Mexican territory to the U.S. He was overthrown by the liberal Revolution of Ayutla in 1855 and lived most of his later years in exile.

Early life and education

Antonio de Padua María Severino López de Santa Anna y Pérez de Lebrón was born in Xalapa, Veracruz, Nueva España (New Spain), on 21 February 1794. He was from a respected Spanish colonial family; he and his parents, Antonio López de Santa Anna and Manuela Pérez de Lebrón, belonged to the elite criollo racial group of American-born Spaniards. His father was a royal army officer perpetually in debt,[12] and served for a time as a sub-delegate for the Gulf Coast Spanish province of Veracruz. However, his parents were wealthy enough to send him to school.

Career

War of Independence, 1810–1821

In June 1810, the 16-year-old Santa Anna joined the Fijo de Veracruz infantry regiment[13] as a cadet against the wishes of his parents, who wanted him to pursue a career in commerce.[14] In September 1810, secular cleric Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla rebelled against Spanish rule, sparking a spontaneous mass movement in Mexico's rich agricultural area, the Bajío. The Mexican War of Independence was to last until 1821, and Santa Anna, like most creole military men, fought for the crown against the mixed-raced insurgents for independence. Santa Anna's commanding officer was José Joaquín de Arredondo, who taught him much about dealing with Mexican rebels. In 1811, Santa Anna was wounded in the left hand by an arrow[15] during the campaign under Col. Arredondo in the town of Amoladeras, in the intendancy (administrative district) of San Luis Potosí. In 1813, Santa Anna served in Texas against the Gutiérrez–Magee Expedition, and at the Battle of Medina, in which he was cited for bravery. He was promoted quickly; he became a second lieutenant in February 1812 and first lieutenant before the end of that year. In the aftermath of the rebellion, the young officer witnessed Arredondo's fierce counter-insurgency policy of mass executions.

During the next few years, in which the war for independence reached a stalemate, Santa Anna erected villages for displaced citizens near the city of Veracruz. He also pursued gambling, a habit that would follow him all through his life. In 1816, Santa Anna was promoted to captain. He conducted occasional campaigns to suppress Native Americans or to restore order after a tumult had begun.

When royalist officer Agustín de Iturbide changed sides in 1821 and allied with insurgent Vicente Guerrero, fighting for independence under the Plan of Iguala, Santa Anna also joined the fight for independence.[16] The changed circumstances in Spain, where liberals had ousted Ferdinand VII and began implementing the Spanish liberal constitution of 1812, made many elites in Mexico reconsider their options.

Rebellion against the Mexican Empire of Iturbide, 1822–1823

Iturbide rewarded Santa Anna with the command of the vital port of Veracruz, the gateway from the Gulf of Mexico to the rest of the nation and site of the customs house. However, Iturbide subsequently removed Santa Anna from the post, prompting Santa Anna to rise in rebellion in December 1822 against Iturbide. Santa Anna already had significant power in his home region of Veracruz, and "he was well along the path to becoming the regional caudillo."[17] Santa Anna claimed in his Plan of Veracruz that he rebelled because Iturbide had dissolved the Constituent Congress. He also promised to support free trade with Spain, an important principle for his home region of Veracruz.[18][19]

Although Santa Anna's initial rebellion was important, Iturbide had loyal military men who were able to hold their own against the rebels in Veracruz. However, former insurgent leaders Vicente Guerrero and Nicolás Bravo, who had supported Iturbide's Plan de Iguala, now returned to their southern Mexico base and raised a rebellion against Iturbide. Then the commander of imperial forces in Veracruz, who had fought against the rebels, changed sides and joined the rebels. The new coalition proclaimed the Plan of Casa Mata, which called for the end of the monarchy, restoration of the Constituent Congress, and creation of a republic and a federal system.[20]

Santa Anna was no longer the main player in the movement against Iturbide and the creation of new political arrangements. He sought to regain his position as a leader and marched forces from Veracruz to Tampico, then to San Luis Potosí, proclaiming his role as the "protector of the federation." San Luis Potosí, and other north-central regions, Michoacán, Querétaro, and Guanajuato met to decide their own position about the federation. Santa Anna pledged his military forces to the protection of these key areas. "He attempted, in other words, to co-opt the movement, the first of many examples in his long career where he placed himself as the head of a generalized movement so it would become an instrument of his advancement."[21]

Santa Anna and the early Mexican Republic

In May 1823, following Iturbide's March abdication as emperor, Santa Anna was sent to command in Yucatán. At the time, Yucatán's capital of Mérida and the port city of Campeche were in conflict. Yucatán's closest trade partner was Cuba, still a Spanish colony. Santa Anna took it upon himself to plan a landing force from Yucatán in Cuba, which he envisioned would result in Cuban colonists welcoming their liberators and most especially Santa Anna. A thousand Mexicans were already on ships to sail to Cuba when word came that the Spanish were reinforcing their colony, so the invasion was called off.[22]

Former insurgent general Guadalupe Victoria, a liberal federalist, became the first president of the Mexican republic in 1824, following the creation of the Federalist Mexican Constitution of 1824. He came to the presidency with little factional conflict and he served out his entire four-year term. However, the election of 1828 was quite different, with considerable political conflict in which Santa Anna became involved. Even before the election, there was unrest in Mexico, with some conservatives affiliated with the Scottish Rite Masons plotting rebellion. The so-called Montaño rebellion in December 1827 called for the prohibition of secret societies, implicitly meaning liberal York Rite Masons, and the expulsion of the U.S. minister in Mexico, Joel Roberts Poinsett, a promoter of federal republicanism in Mexico. Although Santa Anna was believed to be a supporter of the Scottish Rite conservatives, in the Montaño rebellion eventually he threw his support to the liberals. In his home state of Veracruz, the governor had thrown his support to the rebels, and in the aftermath of the rebellion's failure, Santa Anna as vice-governor stepped into the governorship.[23]

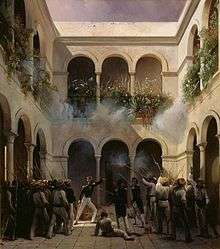

In 1828, Santa Anna supported the hero of the insurgency, Vicente Guerrero, who was a candidate for the presidency. Another important liberal, Lorenzo de Zavala, also supported Guerrero. Manuel Gómez Pedraza won the indirect elections for the presidency, with Guerrero coming in second. Even before all the votes had been counted in September 1828, Santa Anna rebelled against the election results in support of Guerrero. Santa Anna issued a plan at Perote that called for the nullification of the election results, as well for a new law expelling Spanish nationals from Mexico, believed to be in league with Mexican conservatives. Santa Anna's rebellion initially had few supporters, southern Mexican leader Juan Álvarez joined Santa Anna's rebellion, and Lorenzo de Zavala, governor of the state of Mexico, under threat of arrest by the conservative Senate, fled to the mountains and organized his own rebellion against the federal government. Zavala brought the fighting into the capital, with his supporters seizing an armory, the Acordada. In these circumstances, president-elect Gómez Pedraza resigned and soon after left the country. This cleared the way for Guerrero to become president of Mexico. Santa Anna gained prominence as a national leader in his role to oust Gómez Pedraza and as a defender of federalism and democracy.[24] An explanation for Santa Anna's support of Guerrero is that Gómez Pedraza had been in favor of Santa Anna's proposed invasion of Cuba, if successful, and if not, "Mexico might rid himself of an undesirable pest, namely Santa Anna."[25]

In 1829, Santa Anna made his mark in the early republic by leading forces that defeated a Spanish invasion to reconquer Mexico. Spain made a final attempt to retake Mexico, invading Tampico with a force of 2,600 soldiers. Santa Anna marched against the Barradas Expedition with a much smaller force and defeated the Spaniards, many of whom were suffering from yellow fever. The defeat of the Spanish army not only increased Santa Anna's popularity but also consolidated the independence of the new Mexican republic. Santa Anna was declared a hero. From then on, he styled himself "The Victor of Tampico" and "The Savior of the Patria." His main act of self-promotion was to call himself "The Napoleon of the West."

In a December 1829 coup, Vice-President Anastasio Bustamante, a conservative, rebelled against President Guerrero, who left the capital to lead a rebellion in southern Mexico. The capture of Guerrero and his summary trial and execution in 1831 was a shocking event to the nation. The conservatives in power were tainted by the execution of a hero of independence and former president. On 1 January 1830, Bustamante took over the presidency. Bustamante had promised an effective administration, and customs revenues (import and export taxes) increased spectacularly, but the revenues were spent on administrative expenses, but most of it went to the military, to win its support with preferential payments, new equipment, increased recruitment. The policy aimed at buying the army's loyalty, a force that could suppress Mexico's, and collect revenue. On top of customs revenues, Bustamante's government borrowed funds from moneylenders. His government jailed dissenters. In 1832, Santa Anna seized the customs revenues from Veracruz and declared himself in rebellion against Bustamante. The bloody conflict ended with Santa Anna forcing the resignation of Bustamante's cabinet and an agreement was brokered for new elections in 1833. Santa Anna won handily.[26]

"Absentee President," 1833–1835

Santa Anna was elected president on 1 April 1833, but while he desired the title, he was not interested in governing. According to Mexican historian Enrique Krauze, "It annoyed him and bored him, and perhaps frightened him."[27] A biographer of Santa Anna described him in this period as the "absentee president."[28] Santa Anna's vice president, civilian liberal, medical doctor, Valentín Gómez Farías, took over the responsibility of the governing of the nation. Santa Anna retired to his Veracruz hacienda, Manga de Clavo. Gómez Farías was a moderate, but he had a radical liberal congress with which to contend, perhaps a reason that Santa Anna left executive power to his vice president.[29] The nation was faced with an empty treasury and the 11 million peso debt incurred by the Bustamante government. He could not cut back on the bloated expenditures on the army and sought other revenues. Taking a chapter out of the late colonial Spanish reforms, the government targeted the Roman Catholic Church. Anticlericalism was a tenet of Mexican liberalism, and the church had supported Bustamante's government, so targeting that institution was a logical move. Tithing (a 10% tax on agricultural production) was abolished as a legal obligation, and seized church property and finances. The church's role in education was reduced and the Pontifical University closed. All this caused concern among Mexican conservatives.[30] Gómez Farías also sought to extend these reforms to the frontier province of Alta California, promoting legislation to secularize the Franciscan missions there. In 1833 he organized the Híjar-Padrés colony to bolster non-mission civilian settlement. A secondary goal of the colony was to help defend Alta California against perceived Russian colonial ambitions from the trading post at Fort Ross.[31] However, for liberal intellectual and Catholic priest, José María Luis Mora, selling church property was the key to "transforming Mexico into a liberal, progressive nation of small landowners." Sale of nonessential church property would bring in much-needed revenue to the treasury. The army was also targeted for reform, since it was the largest-single expenditure in the national budget. On Santa Anna's suggestion, the number of battalions was to be reduced as well as the number of generals and brigadiers.[32]

A law was issued, the Ley del Caso that called for the arrest of 51 politicians, including former president Bustamante for holding "unpatriotic" beliefs and ordered them expelled from the republic. Gómez Farías claimed that Santa Anna was the driving force for the law, which evidence seems to support.[33] With increasing resistance from the church as well as the army, the Plan of Cuernavaca was issued, likely orchestrated by former general and governor of the Federal District, José María Tornel. The plan called for repeal the Ley del Caso and urged lack of tolerance for the influence of Masonic lodges, where politics was pursued in secrecy; declared void the laws passed by Congress and the local legislatures in favor of the reforms; requested the protection of President Santa Anna to fulfill the plan, and recognize him as the only authority; removal from office the deputies and officials who carried out enforcement of the reform laws and decrees; and provide military force to support the president in implementing the plan.[34]

As the tide turned against the radical reforms, Santa Anna was persuaded to return to the presidency, and Gómez Farías resigned. This set the stage for conservative to reshape Mexico's government from a federalist republic to a unitary central republic.[35]

Santa Anna and the Central Republic, 1835

For conservatives, the liberal reform of Gómez Farías was radical and threatened elites' power. Santa Anna's actions in allowing this first reform (followed by a more sweeping one in 1855) might have been a test case for liberalism. At this point, Santa Anna was a liberal. By giving the moderate liberal Gómez Farías responsibility for the reforms, Santa Anna could have plausible deniability. He could be watchful and wait to see the reaction to a comprehensive attack on the special privileges of the army and the Roman Catholic Church (fueros), as well as confiscation of church wealth, enacted by the radical liberal congress.

Santa Anna was pushed into action. Since he was president and had placed his vice president in charge while he returned to his hacienda, he re-entered the public sphere as the legitimate president. In May 1834, Santa Anna ordered the disarmament of the civic militia. He urged Congress to abolish the controversial Ley del Caso, under which the liberals' opponents had been sent into exile.[36] The Plan of Cuernavaca, published on 25 May 1834, called for repeal of the liberal reforms.[37] On 12 June, Santa Anna dissolved Congress and announced his decision to adopt the Plan of Cuernavaca.[38] Santa Anna formed a new Catholic, centralist, conservative government. During this period, Santa Anna brokered an agreement with the Catholic Church, which had signed on to the Plan of Cuernavaca. In exchange for preserving the Church's and the army's privileges, and the church promised a monthly donation to the government of 30–40,000 pesos.[39] "The santanistas [supporters of Santa Anna] succeeded in achieving what the radicals ha failed to do: forcing the Church to assist the republic's daily fiscal needs with its funds and properties."[40] On 4 January 1835, Santa Anna returned to his hacienda, placing Miguel Barragán as acting president. In 1835, it replaced the 1824 constitution with the new constitutional document known as the "Siete Leyes" ("The Seven Laws"). Santa Anna did not involve himself with the conservative centralists as they moved to replace the federal constitution that dispersed power to the states with a unitary power in the hands of the central government, seemingly uneasy with their political path. "Although he has been blamed for the change to centralism, he was not actually present during any of the deliberations that led to the abolition of the federalist charter or the elaboration of the 1836 Constitution."[41][42]

Several states openly rebelled against the changes: Coahuila y Tejas (the northern part of which would become the Republic of Texas), San Luis Potosí, Querétaro, Durango, Guanajuato, Michoacán, Yucatán, Jalisco, Nuevo León, Tamaulipas, and Zacatecas. Several of these states formed their own governments: the Republic of the Rio Grande, the Republic of Yucatán, and the Republic of Texas. Only the Texans defeated Santa Anna and retained their independence. Their fierce resistance was possibly fueled by reprisals Santa Anna committed against his defeated enemies.[43] The New York Post editorialized that "had [Santa Anna] treated the vanquished with moderation and generosity, it would have been difficult if not impossible to awaken that general sympathy for the people of Texas which now impels so many adventurous and ardent spirits to throng to the aid of their brethren."[44]

The Zacatecas militia, the largest and best supplied of the Mexican states, led by Francisco García Salinas, was well armed with .753 caliber British 'Brown Bess' muskets and Baker .61 rifles. But, after two hours of combat on 12 May 1835, Santa Anna's "Army of Operations" defeated the Zacatecan militia and took almost 3,000 prisoners. Santa Anna allowed his army to loot Zacatecas for forty-eight hours. After defeating Zacatecas, he planned to move on to Coahuila y Tejas to quell the rebellion there, which was being supported by settlers from the United States (aka Texians).

Texas Revolution 1835–1836

In 1835, Santa Anna repealed the Mexican Constitution, which ultimately led to the beginning of the Texas Revolution. Santa Anna's reasoning for the repeal was that American settlers in Texas were not paying taxes or tariffs, claiming they were not recipients of any services provided by the Mexican Government. As a result, new settlers were not allowed there. The new policy was a response to the U.S. attempts to purchase Texas from Mexico.[45]

Santa Anna's treatment of the people of Texas also led to the revolution. In 1834, Santa Anna abolished the state legislature and gave himself absolute power, and as a result, the people in Texas were considered by Santa Anna to be a part of an illegitimate government. The first altercation occurred in September 1835, when General Cos of the Mexican Army ordered men to confiscate a cannon from Gonzales. The people of Texas resisted, gaining control of the Alamo.[45]

Like other states discontented with the central Mexican government, the Texas Department of the Mexican state of Coahuila y Tejas rebelled in late 1835 and declared itself independent on 2 March 1836. The northeastern part of the state had been settled by numerous Anglo-American immigrants. Stephen Austin and his party had been welcomed by earlier Mexican governments.

Santa Anna marched north to bring Texas back under Mexican control by a show of brute merciless force. His expedition posed challenges of manpower, logistics, supply, and strategy far beyond what he was prepared for, and it ended in disaster. To fund, organize, and equip his army he relied, as he often did, on forcing wealthy men to provide loans. He recruited hastily, sweeping up many derelicts and ex-convicts, as well as Indians who could not understand Spanish commands.

His army expected tropical weather and suffered from the cold as well as shortages of traditional foods. Stretching a supply line far longer than ever before, he lacked horses, mules, cattle, and wagons, and thus had too little food and feed. The medical facilities were minimal. Morale sank as soldiers realized there were not enough chaplains to properly bury their bodies. Regional Indians attacked military stragglers; water sources were polluted and many men were sick. Because of his weak staff system, Santa Anna was oblivious to the challenges, and was totally confident that a show of force and a few massacres (as at the Alamo and Goliad) would have the rebels begging for mercy.[46]

On 6 March 1836, at the Battle of the Alamo, Santa Anna's forces killed 189 Texan insurgents and later executed more than 342 Texan prisoners, including James Fannin at the Goliad Massacre (27 March 1836). These executions were conducted in a manner similar to the executions he witnessed of Mexican rebels in the 1810s as a young soldier. However, Santa Anna's forces suffered unexpectedly heavy casualties in the battle.

In 1874, Santa Anna asserted in a letter that killing the Alamo insurgents was his only option. The letter stressed that Alamo garrison commander William B. Travis was to blame for the degree of violence at the Alamo. Santa Anna believed that Travis was rude and disrespectful towards him, and had that not happened, he would have allowed Sam Houston to establish a dominant presence there. In his letter, he stated that the disrespect of Travis led to the demise of all of his followers, which he claimed only took a couple of hours.[47]

The Mexican army victory at the Alamo bought time for General Sam Houston and his Texas forces. During the siege of the Alamo, the Texas Navy had more time to plunder ports along the Gulf of Mexico and the Texian Army gained more weapons and ammunition. Despite Houston's lack of ability to maintain strict control of the Texian Army, they completely routed Santa Anna's much larger army at the Battle of San Jacinto on 21 April 1836. The Texans shouted, "Remember Goliad, Remember the Alamo!" The day after the battle, a small Texan force led by James Austin Sylvester captured Santa Anna. They found the general dressed in a dragoon private's uniform and hiding in a marsh.

On 14 May 1836, a treaty was drawn up between Santa Anna and Texas, committing Santa Anna to cease operations against the rebels. Santa Anna also agreed that his troops would leave Texas. Both armies were prohibited from contact with each other. Finally, the treaty demanded that all Texan prisoners under Santa Anna be released. The treaty was a major turning point in Santa Anna's career, as it meant the end of Mexican sovereignty in Texas.[48]

Santa Anna rode double into Sam Houston's camp on the horse of Joel Walter Robison, a soldier in most of the battles and later a member of the Texas House of Representatives from Fayette County.[49]

Acting Texas president David G. Burnet and Santa Anna signed the Treaties of Velasco, the latter under duress, stating that "in his official character as chief of the Mexican nation, he acknowledged the full, entire, and perfect Independence of the Republic of Texas." In exchange, Burnet and the Texas government guaranteed Santa Anna's safety and transport to Veracruz. During this week-long journey, Santa Anna passed through Washington D.C. where he met briefly with the president Andrew Jackson. Meanwhile, in Mexico City a new government declared that Santa Anna was no longer president and that the treaty he had made with Texas was null and void. The Mexican Congress also rejected the treaty. While Santa Anna was captive in Texas, Joel Roberts Poinsett – U.S. minister to Mexico in 1824 – offered a harsh assessment of General Santa Anna's situation: "Say to General Santa Anna that when I remember how ardent an advocate he was of liberty ten years ago, I have no sympathy for him now, that he has gotten what he deserves." Santa Anna replied: "Say to Mr. Poinsett that it is very true that I threw up my cap for liberty with great ardor, and perfect sincerity, but very soon found the folly of it. A hundred years to come my people will not be fit for liberty. They do not know what it is, unenlightened as they are, and under the influence of Catholic clergy, a despotism is a proper government for them, but there is no reason why it should not be a wise and virtuous one."[50]

Redemption, dictatorship, and exile

After some time in exile in the U.S., and after meeting U.S. president Andrew Jackson in 1837, Santa Anna was allowed to return to Mexico. He was transported aboard the USS Pioneer to retire to his hacienda in Veracruz, called Manga de Clavo.

In 1837, Santa Anna also wrote a manifesto in which he reflected on his Texas experiences as well as his surrender. His great impact on Mexico was that by the age of thirty-five, he had built such a strong reputation as a military leader that he obtained high ranking. He acknowledged that by 1835, he considered Texas to be the biggest threat to Mexico, and he acted upon those threats.[51]

In 1838, Santa Anna had a chance for redemption from the loss of Texas. After Mexico rejected French demands for financial compensation for losses suffered by French citizens, France sent forces that landed in Veracruz in the Pastry War. The Mexican government gave Santa Anna control of the army and ordered him to defend the nation by any means necessary. He engaged the French at Veracruz. During the Mexican retreat after a failed assault, Santa Anna was hit in the left leg and hand by cannon fire. His shattered ankle required amputation of much of his leg, which he ordered buried with full military honors. Despite Mexico's final capitulation to French demands, Santa Anna used his war service to re-enter Mexican politics.

Santa Anna used a prosthetic cork leg; during the later Mexican–American War, it was captured and kept by American troops from the 4th Illinois Infantry. The cork leg is displayed at the Illinois State Military Museum in Springfield.[52] A second leg, a peg, was also captured by the 4th Illinois, and was reportedly used by the soldiers as a baseball bat; it is displayed at the home of Illinois Governor Richard J. Oglesby (who served in the regiment) in Decatur.[53] Santa Anna had a replacement leg made which is displayed at the Museo Nacional de Historia in Mexico City.[54]

Soon after, as Anastasio Bustamante's presidency turned chaotic, supporters asked Santa Anna to take control of the provisional government. Santa Anna was made president for the fifth time, taking over a nation with an empty treasury. The war with France had weakened Mexico, and the people were discontented. Also, a rebel army led by Generals José Urrea and José Antonio Mexía was marching towards the capital in opposition to Santa Anna. Commanding the army, Santa Anna crushed the rebellion in Puebla.

Santa Anna ruled in a more dictatorial way than during his first administration. His government banned anti-Santanista newspapers and jailed dissidents to suppress opposition. In 1842, he directed a military expedition into Texas. It inflicted numerous casualties with no political gain, but Texans began to be persuaded of the potential benefits of annexation by the more powerful U.S. Santa Anna was unable to control the Mexican congressional elections of 1842. The new Congress was composed of men of principles who vigorously opposed the autocratic leader.[55]

Trying to restore the treasury, Santa Anna raised taxes, but this aroused resistance. Several Mexican states stopped dealing with the central government, and Yucatán and Laredo declared themselves independent republics. With resentment growing, Santa Anna stepped down from power and fled in December 1844. The buried leg he left behind in the capital was dug up by a mob and dragged through the streets until nothing was left of it.[56][57] Fearing for his life, he tried to elude capture, but in January 1845 he was apprehended by a group of Native Americans near Xico, Veracruz. They turned him over to authorities, and Santa Anna was imprisoned. His life was spared, but he was exiled to Cuba, still a Spanish colony.

Mexican–American War, 1846–1848

In 1846, Mexican and American troops moved towards the Rio Grande into the disputed Nueces Strip. Following early skirmishes, the United States then declared war on Mexico. A coalition including Juan Alvarez forced out President Mariano Paredes, and sought a return to a federal republic with Santa Anna as president. Paredes was overthrown on 4 August 1846 and Santa Anna returned to Mexico from exile two days later. Mexico returned to the Constitution of 1824 as its governing document. Santa Anna wrote to Mexico City saying he had no aspirations to the presidency, but would eagerly use his military experience to reclaim Texas. Santa Anna had secretly been dealing with representatives of the U.S., pledging that if he were allowed back in Mexico through the U.S. naval blockades, he would work to sell all contested territory to the U.S. at a reasonable price. Once back in Mexico at the head of an army, Santa Anna reneged on both of these agreements, which had been a ruse to return to Mexico and lead the fight against the U.S. invasion. It had only been a year since he was forced out of the republic, but Santa Anna was still popular among the Mexican people. Although he had a history of double-dealing and corruption, many Mexicans acknowledged that Santa Anna was the most reliable person to help Mexico get through the many obstacles and threats that the country would often face. His return was different from past events because Santa Anna had no intention of getting involved in politics again, intending to solely focus on aiding the military in its war against the United States.[58] "Despite his many faults as a tactician and his overbearing political ambition, Santa Anna was committed to fighting to the bitter end. His actions would prolong the war for at least a year, and more than any other single person it was Santa Anna who denied Polk's dream of a short war."[59]

President for the last time, 1853-55

Following defeat in the Mexican–American War in 1848, Santa Anna went into exile in Kingston, Jamaica. Two years later, he moved to Turbaco, Colombia. In April 1853, he was invited back by conservatives who had overthrown a weak liberal government, initiated under the Plan de Hospicio in 1852, drawn up by the clerics in the cathedral chapter of Guadalajara. Usually, revolts were fomented by military officers; this one was created by churchmen.[60] Santa Anna was elected president on 17 March 1853; Lucas Alamán became his Minister of Foreign Relations, although he died a short time later in June 1853. Santa Anna honored his promises to the Church, revoking a decree denying protection for the fulfillment of monastic vows, a reform promulgated twenty years earlier during the era of Valentín Gómez Farías. President Santa Anna had left running the government in 1833 to his liberal vice president.[61] The Jesuits, who had been expelled from Spanish realms by the crown in 1767, were allowed to return to Mexico ostensibly to educate poorer classes, and much of their property, which the crown had confiscated and sold, was restored to them.[61]

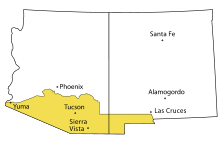

Although he gave himself exalted titles, Santa Anna's situation was quite vulnerable. He declared himself dictator-for-life with the title "Most Serene Highness." His full title in this final period of power was "Hero [benemérito] of the nation, General of Division, Grand Master of the National and Distinguished Order of Guadalupe, Grand Cross of the Royal and Distinguished Spanish Order of Carlos III, and President of the Mexican Republic."[62] The reality was that this administration was no more successful than his earlier ones, dependent on loans from moneylenders and support from conservative elites, the church, and the army. A major miscalculation was his sale of territory to the U.S., the Gadsden Purchase. La Mesilla, the land in northwest Mexico that the U.S. wanted, was much easier terrain for the building of a transcontinental railway line in the U.S. The purchase money for the land was supposedly to go to Mexico's empty treasury. Santa Anna was unwilling to wait until the final transaction went through and the boundary line established, wanting access to the $3M immediately. He bargained with American bankers to get immediate cash, while they gained the right to the revenue when the sale closed. His short-sighted deal netted the Mexican government only $250,000 against credit of $650,000 going to the bankers. Gadsden thought the amount was likely much higher.[63]

Liberals created the Plan of Ayutla, calling for the removal of Santa Anna from office. He was exiled yet again.

Despite his generous payoffs to the military for loyalty, by 1855 even conservative allies had seen enough of Santa Anna. That year a group of liberals led by Benito Juárez and Ignacio Comonfort overthrew Santa Anna, and he fled back to Cuba. As the extent of his corruption became known, he was tried in absentia for treason; all his estates were confiscated by the government.

Personal life

Santa Anna married twice, both times to wealthy teenage girls. At neither wedding ceremony did he appear, legally empowering his future father-in-law to serve as a proxy at his first wedding and a friend at his second.[64] One assessment of the two marriages is that they were arranged marriages of convenience, bringing considerable wealth to Santa Anna and that his lack of attendance at the wedding ceremonies "appears to confirm that he was purely interested in the financial aspect on the alliance."[65]

In 1825, he married Inés García, the daughter of wealthy Spanish parents in Veracruz, and the couple had four children: María de Guadalupe, María del Carmen, Manuel, and Antonio López de Santa Anna y García.[66] By 1825, Santa Anna had distinguished himself as a military man, joining the movement for independence when other creoles were also seeing Mexican autonomy as the way forward under royalist turned insurgent Agustín de Iturbide and the Army of Three Guarantees. When Iturbide as Mexican emperor lost support, Santa Anna had been in the forefront of leaders seeking to oust him. Although Santa Anna's family was of modest means, he was of good creole lineage; the García family may well have seen a match between their young daughter and the up-and-coming Santa Anna as advantageous. María Inés's dowry allowed Santa Anna to purchase the first of his haciendas, Manga de Clavo, in Veracruz state.[65][67]

The wife of the first Spanish Ambassador to Mexico, Fanny Calderón de la Barca and her husband visited with Santa Anna's first wife Inés at Manga de Clavo, where they were well-received with a breakfast banquet. Mme. Calderón de la Barca observed that "After breakfast, the Señora having dispatched an officer for her cigar-case, which was gold with a diamond latch, offered me a cigar, which I having declined, she lighted her own, a little paper 'cigarette', and the gentlemen followed her good example."[68]

Two months after the death of his wife Inés García in 1844, the 50-year-old Santa Anna married 16-year-old María de Los Dolores de Tosta. The couple rarely lived together; de Tosta resided primarily in Mexico City and Santa Anna's political and military activities took him around the country.[69] They had no children, leading biographer Will Fowler to speculate that the marriage was either primarily platonic or that de Tosta was infertile.[69]

Several women claimed to have borne Santa Anna natural children. In his will, Santa Anna acknowledged and made provisions for four: Paula, María de la Merced, Petra, and José López de Santa Anna. Biographers have identified three more: Pedro López de Santa Anna, and Ángel and Augustina Rosa López de Santa Anna.[66]

Later years and death

From 1855 to 1874, Santa Anna lived in exile in Cuba, the United States, Colombia, and the then Danish island of Saint Thomas. He had left Mexico due to his unpopularity with the Mexican people after his defeat in 1848 and traveled to and from Cuba, the United States, and Europe. He participated in gambling and businesses with the hopes that he would become rich. In the 1850s, he traveled to New York with the first shipment of chicle. This is the base of what we know today as chewing gum, however, Santa Anna intended chicle to be used in buggy tires. He attempted but was unsuccessful in convincing U.S. wheel manufacturers that this substance could be more useful in tires than the materials they were originally using. Although he introduced chewing gum to the United States, he did not make any money from the product.[9]

In 1865, he attempted to return and offer his services during the French invasion by posing once again as the country's defender and savior, only to be refused by Juárez who was well aware of Santa Anna's character. Later that year a schooner owned by Gilbert Thompson, son-in-law of Daniel Tompkins, brought Santa Anna to his home in Staten Island, New York,[70] where he tried to raise money for an army to return and take over Mexico City.

Thomas Adams, the American assigned to aid Santa Anna while he was in the U.S., experimented with chicle in an attempt to use it as a substitute for rubber. He bought one ton of the substance from Santa Anna, but his experiments proved unsuccessful. Instead, Adams helped to found the chewing gum industry with a product that he called "chiclets."[71]

During his many years in exile, Santa Anna was a passionate fan of the sport of cockfighting. He had many roosters that he entered into competitions, and would have his roosters compete with cocks from all over the world.[9] He would invite breeders from all over the world for matches and is known to have spent tens of thousands of dollars on prize roosters.

In 1874, he took advantage of a general amnesty and returned to Mexico. Crippled and almost blind from cataracts, he was ignored by the Mexican government that same year at the anniversary of the Battle of Churubusco. Having retreated from politics in 1855, he remained disconnected until his death in 1876.[9] Santa Anna died at his home in Mexico City on 21 June 1876 at age 82. He was buried with full military honors in a glass coffin in Panteón del Tepeyac Cemetery.

See also

- History of democracy in Mexico

- List of heads of state of Mexico

Note

- Some accounts differ on the number of terms that he served, distinguishing between occasions on which Santa Anna was elected or appointed to the presidency and those when he returned to the office during the same term after previously leaving it in the hands of others. For example, Will Fowler shows him serving six terms in his introduction to Santa Anna of Mexico,[8] while the Texas State Historical Association claims five.[1]

References

Citations

- Callcott, Wilfred H., "Santa Anna, Antonio Lopez De," Handbook of Texas Online. Retrieved 18 April 2017.

- Howe, Daniel Walker (2007), What Hath God Wrought: The Transformation of America, 1815–1848, Oxford Univ. Press, p. 660

- For example, Costeloe, Michael P. The Central Republic in Mexico, 1835–1846: Hombres de Bien in the Age of Santa Anna. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press 1993.

- Krauze, Enrique. Mexico: Biography of Power. New York: Harper Collins 1997, 88.

- Archer, Christon I. "Fashioning a New Nation" in Michael C. Meyer and William H. Beezley, eds. The Oxford History of Mexico (2000) p. 323

- Long, Jeff (1990), Duel of Eagles, The Mexican and U.S. However, he is still seen as a tyrant in mexican history. Fight for the Alamo, Quill, p. 85

- Alamán, Lucas. Historia de México vol. 5. Mexico 1990, quoted in Krauze, Enrique. Mexico: Biography of Power. New York: HarperCollins 1997, p. 135.

- Fowler 2009, p. xxi.

- Mead, Teresa (2016). A History of Modern Latin America. UK: John Wiley & Sons Inc. pp. 126–127. ISBN 978-1405120517.

- Archer, Christon I. "Fashioning a New Nation" in Michael C. Meyer and William H. Beezley, eds. The Oxford History of Mexico (2000) p. 322

- Guardino, Peter. The Dead March: A History of the Mexican-American War. Cambridge: Harvard University Press 2017, p. 88

- Krauze, Mexico: Biography of Power, p. 127.

- Pani, Erika. "Antonio López de Santa Anna" in Encyclopedia of Mexico. Chicago: Fitzroy Dearborn 1997, p. 1334.

- Fowler 2000, p. 20.

- Fowler 2009, p. 27.

- Pani, "Antonio López de Santa Anna", p. 1334.

- Anna, Timothy E. Forging Mexico, 1821–1835. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press 1998, p. 103.

- Anna, Forging Mexico, p. 104.

- Benson, Nettie Lee. "The Plan of Casa Mata", Hispanic American Historical Review 25, no. 1, (February 1945): 45–56.

- Anna, Forging Mexico, p. 107.

- Anna, Forging Mexico, p. 133.

- Green, Stanley C. The Mexican Republic: The First Decade 1823–1832. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press 1987, pp. 44–45.

- Anna, Forging Mexico, pp. 205–206.

- Anna, Forging Mexico, pp. 218–219, 224.

- Green, The Mexican Republic, p. 158.

- Tenenbaum, The Politics of Penury, p. 37

- Krauze, Mexico: Biography of Power, p. 137.

- Fowler, Will. Santa Anna of Mexico, chapter 7, "The Absentee President, 1832-1835", pp. 133-157

- Fowler, Santa Anna of Mexico, p. 143.

- Costeloe, Michael P. (1974). "Santa Anna and the Gómez Farías Administration in Mexico, 1833-1834". The Americas. 31 (1): 18–50. doi:10.2307/980380. JSTOR 980380.

- Hutchinson, C. Alan (1969). Frontier Settlement in Mexican California; The Híjar-Padrés Colony and Its Origins, 1769–1835. New Haven: Yale University Press. OCLC 23067.

- Fowler, Santa Anna of Mexico, p. 145.

- Fowler, Santa Anna of Mexico, p. 420

- González Pedrero, Enrique (2004). País de un solo hombre: el México de Santa Anna. Volumen II. La sociedad de fuego cruzado 1829-1836 (in Spanish). México: Fondo de Cultura Económica. ISBN 968-16-6377-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Tenenbaum, The Politics of Penury, pp. 38-40.

- González Pedrero 2004, p. 468.

- González Pedrero 2004, pp. 471–472.

- Olavarría y Ferrari 1880, p. 344.

- Tenenbaum, Barbara. México en la época de los agiotistas, 1821-1857. Mexico City: El Colegio de México 1985, p. 64.

- Fowler, Santa Anna of Mexico, p. 157.

- Fowler, Santa Anna of Mexico, p. 158

- Costeloe, The Central Republic, 1835-1846, pp. 46-65.

- Edmondson, J.R. The Alamo Story: From Early History to Current Conflicts (2000) p. 378.

- Lord (1961), p. 169.

- Wright, R. "Santa Anna and the Texas Revolution". Andrews University. Retrieved 2 October 2018.

- Presley, James. "Santa Anna's Invasion of Texas: A Lesson in Command", Arizona & the West, (1968) 10#3 pp. 241–252

- "Santa Anna to McArdle, March 16, 1874: Letter Explaining Why the Alamo Insurgents Had to Be Killed". Texas State Library and Archives Commission. the State of Texas.

- animatedatlas.com/mexwar/santaanna.html" 'Treaty' Between Santa Anna and Texas"

- "Robison, Joel Walter". Texas State Historical Association. Retrieved 2 August 2015.

- "Captivity of Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna". Archived from the original on 15 February 2012. Retrieved 10 September 2006.

- tamu.edu, "Manifesto which General Antonio Lopez De Santa Anna Addresses to His Fellow Citizens",

- "Public Displays: Santa Anna's life and limb", by S.L. Wisenberg, Chicago Reader, Retrieved June 2014

- "Captured Leg of Santa Anna", Roadside America

- "Santa Anna's Leg Took a Long Walk", Latin American Studies

- Costeloe, Michael P. (1989). "Generals versus Politicians: Santa Anna and the 1842 Congressional Elections in Mexico". Bulletin of Latin American Research. 8 (2): 257–274. doi:10.2307/3338755. JSTOR 3338755.

- Camnitzer 2009.

- Fowler 2009, p. 239.

- Fowler, Santa Anna of Mexico, pp. 256–257

- Guardino The Dead March, p. 88.

- Lloyd (1966). Church and State in Latin America, revised edition. Chapel Hill: the University of North Carolina Press. p. 358.

- Mecham, Church and State, pp. 358–359.

- Mecham, Church and State, p. 359.

- Tenenbaum, The Politics of Penury, p. 138

- Fowler, Will. "All the President's Women: The Wives of General Antonio López de Santa Anna in 19th century Mexico", Feminist Review, No. 79, Latin America: History, war, and independence (2005), pp. 57–58.

- Fowler, "All the President's Women", p. 58.

- Fowler 2009, p. 92.

- Potash, Robert. "Testaments de Santa Anna." Historia Mexicana, Vol. 13, No. 3, 430–440.

- Calderón de la Barca, F. Life in Mexico. London: Century, pp. 32–33.

- Fowler 2009, p. 229.

- Mex general’s Staten ex-isle Retrieved 22 November 2018

- Staten Island on the Web: Famous Staten Islanders Archived 27 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine

Sources

- Camnitzer, Luis (2009). Weiss, Rachel (ed.). On Art, Artists, Latin America, and Other Utopias. University of Texas Press. p. 199. ISBN 9780292783492.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Fowler, Will (2000). Tornel and Santa Anna: the writer and the caudillo, Mexico, 1795–1853. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 20. ISBN 978-0-313-30914-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Fowler, Will (1 November 2009). Santa Anna of Mexico. U of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0-8032-2638-8. Retrieved 17 August 2012.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- González Pedrero, Enrique (2004). País de un solo hombre: el México de Santa Anna. Volumen II. La sociedad de fuego cruzado 1829–1836 (in Spanish). México: Fondo de Cultura Económica. ISBN 968-16-6377-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Olavarría y Ferrari, Enrique de (1880). Vicente Riva Palacio (ed.). México a través de los siglos (in Spanish). México: Ballescá y Cía. pp. 210–226.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Mead, Teresa (2016). A History of Modern Latin America (2 ed.). UK: John Wiley & Sons Inc. pp. 126–127. ISBN 978-1405120517.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading

- Anna, Timothy E. Forging Mexico, 1821–1835. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press 1998

- Calcott, Wilfred H. Santa Anna: The Story of the Enigma Who Once Was Mexico. Hamden CT: Anchon, 1964.

- Chartrand, Rene, and Younghusband, Bill. Santa Anna's Mexican Army 1821–48 (2004) excerpt and text search

- Costeloe, Michael P. The Central Republic in Mexico, 1835–1846: Hombres de Bien in the Age of Santa Anna. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press 1993.

- Crawford, Ann F.; The Eagle: The Autobiography of Santa Anna; State House Press;

- Fowler, Will (2007), Santa Anna of Mexico, Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press; a standard scholarly biography; online

- Fowler, Will. Mexico in the Age of Proposals, 1821–1853 (1998)

- Fowler, Will. Tornel and Santa Anna: The Writer and the Caudillo, Mexico, 1795–1853 (2000) excerpt and text search

- Green, Stanley C. The Mexican Republic: The First Decade 1823–1832. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press 1987

- Hardin, Stephen L., and McBride, Angus. The Alamo 1836: Santa Anna's Texas Campaign (2001) excerpt and text search

- Jackson, Jack. "Santa Anna's 1836 Campaign: Was It Directed Toward Ethnic Cleansing?" Journal of South Texas (March 2002) 15#1 pp. 10–37; argues that yes it was

- Jackson, Jack, and Wheat, John. Almonte's Texas, Texas State Historical Assoc.

- Krauze, Enrique, Mexico: Biography of Power. New York: HarperCollins 1997. ISBN 0-06-016325-9

- Lord, Walter (1961), A Time to Stand, Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, ISBN 0-8032-7902-7, popular history

- Mabry, Donald J., "Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna", 2 November 2008; essay by scholar

- Roberts, Randy & Olson, James S., A Line in the Sand: The Alamo in Blood and Memory (2002)

- Santoni, Pedro; Mexicans at Arms-Puro Federalist and the Politics of War TCU Press;

- Schein, Robert L. Santa Anna: A Curse Upon Mexico (2003) excerpt and text search

- Suchlicki, Jaime. "Mexico: Montezuma to the Rise of Pan", Potomac Books: Washington DC, 1996.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Antonio López de Santa Anna. |

| Wikisource has the text of an Encyclopaedia Britannica (9th ed.) article about Antonio López de Santa Anna. |

- Santa Anna Letters on the Portal to Texas History

- Antonio López de Santa Anna in A Continent Divided: The U.S. – Mexico War, Center for Greater Southwestern Studies, the University of Texas at Arlington

- The Handbook of Texas Online: Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna

- Benson Latin American Collection – Antonio López de Santa Anna Collection

- Sketch of Santa Anna from A pictorial history of Texas, from the earliest visits of European adventurers to A.D. 1879, hosted by the Portal to Texas History.

- Archontology.org, Home » Nations » Mexico » Heads of State » LÓPEZ de SANTA ANNA, Antonio

- Texas Prisoners in Mexico 3 August 1843 From Texas Tides

| Political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Valentín Gómez Farías |

President of Mexico 17 May – 4 June 1833 |

Succeeded by Valentín Gómez Farías |

| President of Mexico 18 June – 5 July 1833 | ||

| President of Mexico 27 October – 15 December 1833 | ||

| President of Mexico 24 April 1834 – 27 January 1835 |

Succeeded by Miguel Barragán | |

| Preceded by Anastasio Bustamante |

Interim President of Mexico 20 March – 10 July 1839 |

Succeeded by Nicolás Bravo |

| Preceded by Francisco Javier Echeverría |

Provisional President of Mexico 10 October 1841 – 26 October 1842 | |

| Preceded by Nicolás Bravo |

Provisional President of Mexico 4 March – 4 October 1843 |

Succeeded by Valentín Canalizo |

| Preceded by Valentín Canalizo |

Provisional President of Mexico 4 June – 12 September 1844 |

Succeeded by José Joaquín de Herrera |

| Preceded by Valentín Gómez Farías |

Interim President of Mexico 21 March – 2 April 1847 |

Succeeded by Pedro María de Anaya |

| Preceded by Pedro María de Anaya |

Interim President of Mexico 20 May – 15 September 1847 |

Succeeded by Manuel de la Peña y Peña |

| Preceded by Manuel María Lombardini |

Dictator-President of Mexico 20 April 1853 – 9 August 1855 |

Succeeded by Martín Carrera |