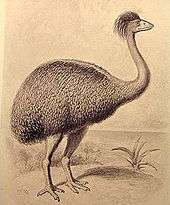

Elephant bird

Elephant birds are members of the extinct ratite family Aepyornithidae, made up of large to enormous flightless birds that once lived on the island of Madagascar. They became extinct, perhaps around 1000–1200 CE, probably as a result of human activity. Elephant birds comprised the genera Mullerornis, Vorombe and Aepyornis. While they were in close geographical proximity to the ostrich, their closest living relatives are kiwi, suggesting that ratites did not diversify by vicariance during the breakup of Gondwana but instead evolved from ancestors that dispersed more recently by flying.

| Elephant birds | |

|---|---|

| |

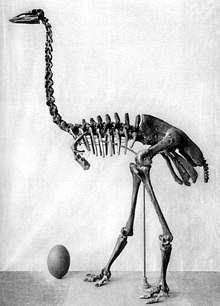

| Aepyornis maximus skeleton and egg | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Clade: | Novaeratitae |

| Order: | †Aepyornithiformes Newton, 1884[1] |

| Family: | †Aepyornithidae Bonaparte, 1853[1] |

| Type species | |

| †Aepyornis maximus Hilaire, 1851 | |

| Genera | |

| |

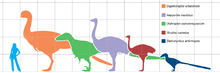

In September 2018, scientists determined that Vorombe titan reached weights of 730 kg (1,600 lb) and stood 3 m (9.8 ft) tall, making it the world's largest bird, slightly larger than the much-older Dromornis stirtoni.

Description

Elephant birds have been extinct since at least the 17th century. Étienne de Flacourt, a French governor of Madagascar in the 1640s and 1650s, mentions an ostrich-like bird said to inhabit unpopulated regions, though it is unclear whether he was repeating folk tales passed on from generations earlier. In 1659, Flacourt wrote of the "vouropatra – a large bird which haunts the Ampatres and lays eggs like the ostriches; so that the people of these places may not take it, it seeks the most lonely places."[2][3] Marco Polo also mentioned hearing stories of very large birds during his journey to the East during the late 13th century. These accounts are today believed to describe elephant birds.[4][3]

Between 1830 and 1840 European travelers in Madagascar saw giant eggs and egg shells.[3] English observers were more willing to believe the accounts of giant birds and eggs because they knew of the moa in New Zealand. In 1851 the French Academy of Sciences received three eggs and some bone fragments.[3] In some cases the eggs have a length up to 34 cm (13 in), the largest type of bird egg ever found.[5] The egg weighed about 10 kg (22 lb).[6] The egg volume is about 160 times greater than that of a chicken egg.[7]

Aepyornis is believed to have been more than 3 m (9.8 ft) tall and weighed perhaps in the range of 350 to 500 kg (770 to 1,100 lb).[8][9][10][11][3] In September 2018, scientists reported that Vorombe titan reached weights of 730 kg (1,600 lb), and based on a fragmentary femur, possibly up to 860 kg (1,900 lb), making it the world's largest bird.[12][13][14] Only the much older species Dromornis stirtoni from Australia rivals it in size among known fossil birds.[15] In the same report, the upper weight limits for A. maximus and D. stirtoni were revised to 540 and 730 kg, respectively.

Species

Four species are usually accepted in the genus Aepyornis today,[16] but the validity of some is disputed, with numerous authors treating them all in just one species, A. maximus. Up to three species are generally included in Mullerornis.[8]

- Order Aepyornithiformes Newton 1884 [Aepyornithes Newton 1884; Epyornisi; Aepiornithes Stejneger 1885; Aepiornithiformes Ridgway 1901][16]

- Family Aepyornithidae (Bonaparte 1853) [Epyornithinae Bonaparte 1853; Aepyornithinae (Bonaparte 1853)]

- Genus Aepyornis Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire 1850[17]

- Aepyornis gracilis Monnier, 1913[1] (Gracile elephant-bird)

- Aepyornis hildebrandti Burckhardt, 1893 [Aepyornis mulleri Milne-Edwards & Grandidier 1894; Aepyornis minimus ] [1] (Hildebrandt's elephant-bird)

- Aepyornis maximus Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire, 1851 [Aepyornis modestus Milne-Edwards & Grandidier, 1869][1] (Giant elephant-bird)

- Aepyornis medius Milne-Edwards & Grandidier, 1866 [Aepyornis grandidieri Rowley, 1867; Aepyornis cursor Milne-Edwards & Grandidier, 1894; Aepyornis lentus Milne-Edwards & Grandidier, 1894; Aepyornis intermedius ][1] (Medium/greater elephant-bird)

- Genus Mullerornis Milne-Edwards & Grandidier 1894 [Flacourtia Andrews 1895]

- Mullerornis betsilei Milne-Edwards & Grandidier, 1894[18] (Betsile elephant-bird)

- Mullerornis agilis Milne-Edwards & Grandidier, 1894[18] (Agile/coastal elephant-bird)

- Mullerornis rudis Milne-Edwards & Grandidier, 1894 [Flacourtia rudis (Milne-Edwards & Grandidier, 1894) Andrews, 1895][8][18][19] (Robust elephant-bird)

- ?Mullerornis grandis Lamberton 1934

- Genus Vorombe Hansford & Turvey, 2018[12]

- Vorombe titan Andrews 1894 [Aepyornis titan Andrews 1894; Aepyornis ingens Milne-Edwards and Grandidier, 1894][12]

- Genus Aepyornis Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire 1850[17]

- Family Aepyornithidae (Bonaparte 1853) [Epyornithinae Bonaparte 1853; Aepyornithinae (Bonaparte 1853)]

Several ratites outside of Madagascar have been posited as "aepyornithid"-like and could potentially make this clade considerably more speciose. These include Eremopezus from the Eocene of North Africa, unnamed Canary Island remains and several Neogene taxa in Eurasia.[20]

Etymology

Aepyornis maximus is commonly known as the 'elephant bird', a term that apparently originated from Marco Polo's account of the rukh in 1298, although he was apparently referring to an eagle-like bird strong enough to "seize an elephant with its talons".[21] Sightings of eggs of elephant birds by sailors (e.g. text on the Fra Mauro map of 1467–69, if not attributable to ostriches) could also have been erroneously attributed to a giant raptor from Madagascar. The legend of the roc could also have originated from sightings of such a giant subfossil eagle related to the African crowned eagle, which has been described in the genus Stephanoaetus from Madagascar,[22] being large enough to carry off large primates; today, lemurs still retain a fear of aerial predators such as these. Another might be the perception of ratites retaining neotenic features and thus being mistaken for enormous chicks of a presumably more massive bird.

The ancient Malagasy name for the bird is vorompatra, meaning "bird of the Ampatres". The Ampatres are today known as the Androy region of southern Madagascar.[21]

Taxonomy and biogeography

Like the ostrich, rhea, cassowary, emu, kiwi and extinct moa, Mullerornis and Aepyornis were ratites; they could not fly, and their breast bones had no keel. Because Madagascar and Africa separated before the ratite lineage arose,[23] Aepyornis has been thought to have dispersed and become flightless and gigantic in situ.[24]

More recently, it has been deduced from DNA sequence comparisons that the closest living relatives of elephant birds are New Zealand kiwi,[25] though they are not particularly closely related, being estimated to have diverged from each other 54 million years ago.[26] Elephant birds are actually part of the mid-Cenozoic Australian ratite radiation; their ancestors flew across the Indian Ocean well after Gondwana broke apart. The existence of possible flying palaeognaths in the Miocene such as Proapteryx further supports the view that ratites did not diversify in response to vicariance. Gondwana broke apart in the Cretaceous and their phylogenetic tree does not match the process of continental drift. Madagascar has a notoriously poor Cenozoic terrestrial fossil record, with essentially no fossils between the end of the Cretaceous (Maevarano Formation) and the Late Pleistocene.[27] Molecular clock estimates from complete mitochondrial genomes obtained from Aepyornis eggshells suggest that Aepyornis and Mullerornis diverged from each other during the mid Oligocene around 27 million years ago, suggesting elephant birds must have been present on Madagascar before this time.[26]

Claims of findings of "aepyornithid" egg remains on the eastern Canary Islands, if valid, would represent a major biogeographical enigma.[28] These islands are not thought to have been connected to mainland Africa when elephant birds were alive. There is no indication that elephant birds evolved outside Madagascar, and today, the Canary Island eggshells are considered to belong to extinct North African birds that may not have been ratites (possibly Eremopezus/Psammornis, or even Pelagornithidae, prehistoric seabirds of immense size). Various "aepyornithid-like" eggs and bones occur in Paleogene and Miocene deposits in Africa and Europe.[29]

Two whole eggs have been found in dune deposits in southern Western Australia, one in the 1930s (the Scott River egg) and one in 1992 (the Cervantes egg); both have been identified as Aepyornis maximus rather than Genyornis. It is hypothesized that the eggs floated from Madagascar to Australia on the Antarctic Circumpolar Current. Evidence supporting this is the finding of two fresh penguin eggs that washed ashore on Western Australia but originated in the Kerguelen Islands, and an ostrich egg found floating in the Timor Sea in the early 1990s.[30]

Biology

Examination of brain endocasts has shown that that both A. maximus and A. hildebrandi had greatly reduced optic lobes, similar to those of their closest living relatives, the kiwis, and consistent with a similar nocturnal lifestyle. The optic lobes of Mullerornis were also reduced, but to a lesser degree, suggestive of a nocturnal or crepuscular lifestyle. A. maximus had relatively larger olfactory bulbs than A. hildebrandi, suggesting that the former occupied forested habitats where the sense of smell is more useful while the latter occupied open habitats.[31]

Diet

Because there is no rainforest fossil record in Madagascar, it is not known for certain if there were species adapted to dense forest dwelling, like the cassowary in Australia and New Guinea today. However, some rainforest fruits with thick, highly sculptured endocarps, such as that of the currently undispersed and highly threatened forest coconut palm Voanioala gerardii, may have been adapted for passage through ratite guts, and the fruit of some palm species are indeed dark bluish purple (e.g. Ravenea louvelii and Satranala decussilvae), just like many cassowary-dispersed fruits.[32]

Reproduction

Occasionally subfossil eggs are found intact.[33] The National Geographic Society in Washington holds a specimen of an Aepyornis egg which was given to Luis Marden in 1967. The specimen is intact and contains the skeleton of the unhatched bird. The Denver Museum of Nature and Science (Denver, Colorado) holds two intact eggs, one of which is currently on display. Another giant Aepyornis egg is on display at the Harvard Museum of Natural History in Cambridge, MA. A cast of the egg is preserved at the Grant Museum of Zoology at London University.

David Attenborough owned an almost complete eggshell, dating from 600 to 700 CE, which he pieced together from fragments that were given to him while making his 1961 BBC series Zoo Quest to Madagascar.[34] In March 2011, the BBC broadcast the 60-minute documentary Attenborough and the Giant Egg, presented by Attenborough, about his personal scientific quest to discover the secrets of the elephant bird and its egg.[34]

A complete eggshell is also available in the collection of the University of Wrocław Museum of Natural History.[35]

There is also an intact specimen of an elephant bird's egg (contrasted with the eggs from other bird species, including a hummingbird's) on display at the Delaware Museum of Natural History, just outside Wilmington, Delaware, US, and another in the Natural History Museum, London.

The Melbourne Museum has two Aepyornis eggs. The first was acquired for £100 by Professor Frederick McCoy in June 1862, and is an intact example. In 1950 it was subjected to radiological examination, which revealed no traces of embryonic material. A second, side-blown Aepyornis egg was acquired at a later date.[36]

The Western Foundation of Vertebrate Zoology, with one of the world's largest collections of avian eggs, has seven Aepyornis egg specimens.[37]

A specimen is also held by the science department at Stowe School in Buckinghamshire, UK.[38]

In the collections of the department of geology at the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago there is a complete, side-blown egg collected, in about 1917, by Rev. Peter A. Bjelde.[39]

A specimen of egg is also held at Regional Museum of Natural History, Bhubaneswar which was donated by former Indian Ambassador Abasar Beuria and his wife Tripti Beuria from their collection.[40]

In April 2013 a specimen was sold at Christie's in London for £66,675[41] The pre-sale estimate had been "more than $45,000".[42]

In April 2018, staff at the Buffalo Museum of Science discovered, after radiographing a giant, cream-colored egg, measuring 12 inches (300 mm) in length and 28 inches (710 mm) in circumference, and weighing over 3 pounds (1.4 kg), that had long been thought to be just a model, was actually an "elephant bird" egg.[43]

Relationship with humans

Extinction

It is widely believed that the extinction of Aepyornis was a result of human activity. The birds were initially widespread, occurring from the northern to the southern tip of Madagascar.[7] One theory states that humans hunted the elephant birds to extinction in a very short time for such a large landmass (the blitzkrieg hypothesis). There is indeed evidence that they were hunted and their preferred habitats destroyed. Eggs may have been particularly vulnerable. 19th-century travelers saw eggshells used as bowls, and a recent archaeological study found remains of eggshells among the remains of human fires,[21][3] suggesting that the eggs regularly provided meals for entire families.

The exact time period when they died out is also not certain; tales of these giant birds may have persisted for centuries in folk memory. There is archaeological evidence of Aepyornis from a radiocarbon-dated bone at 1880 ± 70 BP (approximately 120 CE) with signs of butchering, and on the basis of radiocarbon dating of shells, about 1000 BP (approximately 1000 CE).[7]

An alternative theory is that the extinction was a secondary effect of human impact resulting from transfer of hyperdiseases from human commensals such as chickens and guineafowl. The bones of these domesticated fowl have been found in subfossil sites in the island (MacPhee and Marx, 1997: 188), such as Ambolisatra (Madagascar), where Mullerornis sp. and Aepyornis maximus have been reported.[44] Also reported by these authors, ratite remains have been found in west and south west Madagascar, at Belo-sur-Mer (A. medius, Mullerornis rudis), Bemafandry (M. agilis) and Lamboharana (Mullerornis sp.).

Recently human tool marks have been found on elephant bird bones dating to approximately 10,000 BCE. This not only vastly extends the range of human existence on Madagascar's prehistoric past, but suggests a more complex relationship between these birds and human beings and their eventual extinction, as they apparently coexisted for a massive period of time.[45] However, the absence so far for any evidence of human habitation in the succeeding 6000 years raises difficult questions concerning whether the early human presence might have been temporary, and/or restricted to just a portion of the island.[45]

In art and literature

- The roc (rukh) is known from Sindbad the Sailor's encounter with one in One Thousand and One Nights. Some scholars think the roc is a distorted account of Aepyornis. Historical evidence for this can be found in Megiser (1623).

- H. G. Wells wrote a short story titled "Æpyornis Island" (1894) about the bird. It was first collected in The Stolen Bacillus and Other Incidents (1895).[46]

- Wildlife artist Walton Ford created a painting called Madagascar about the elephant bird in 2002.

See also

- Island gigantism

- Late Quaternary prehistoric birds

- New World Pleistocene extinctions

- Pleistocene megafauna

Notes

- Brands, S. (2008)

- Etienne de Flacourt (1658). Histoire de la grande isle Madagascar. chez Alexandre Lesselin. p. 165. Retrieved 21 May 2013.

- Ley, Willy (August 1966). "Scherazade's Island". For Your Information. Galaxy Science Fiction. pp. 45–55.

- BBC Two Presents (2011)

- Mlíkovsky, J. (2003)

- Spotila, J. R., Weinheimer, C. J., & Paganelli, C. V. (1981). Shell resistance and evaporative water loss from bird eggs: effects of wind speed and egg size. Physiological zoology, 195–202.

- Hawkins, A. F. A. & Goodman, S. M. (2003)

- Davies, S. J. J. F. (2003)

- Alexander, R. M. (1998). "All-time giants: the largest animals and their problems". Palaeontology. 41 (6): 1231–1245.

- Anderson, J. F., Rahn, H., & Prange, H. D. (1979). Scaling of supportive tissue mass. Quarterly Review of Biology, 139–148.

- Alvarenga, H. M., & Höfling, E. (2003). Systematic revision of the Phorusrhacidae (Aves: Ralliformes). Papéis Avulsos de Zoologia (São Paulo), 43(4), 55–91.

- Hansford, J. P.; Turvey, S. T. (2018-09-26). "Unexpected diversity within the extinct elephant birds (Aves: Aepyornithidae) and a new identity for the world's largest bird". Royal Society Open Science. 5 (9): 181295. Bibcode:2018RSOS....581295H. doi:10.1098/rsos.181295. PMC 6170582. PMID 30839722.

- Zoological Society of London (25 September 2018). "ZSL names world's largest ever bird -- Vorombe titan - Madagascar's giant elephant birds receive 'bone-afide' rethink". EurekAlert!. Retrieved 26 September 2018.

- Quenqua, Douglas (26 September 2018). "The Elephant Bird Regains Its Title as the Largest Bird That Ever Lived – A study finds that one member of a previously unidentified genus of the birds could have weighed more than 1,700 pounds". The New York Times. Retrieved 26 September 2018.

- Deeming, D. C.; Birchard, G. F. (2009). "Why were extinct gigantic birds so small?". Avian Biology Research. 1 (4): 187–194. doi:10.3184/175815508x402482.

- Brodkorb, Pierce (1963)

- Julian P. Hume; Michael Walters (2012). Extinct birds. T&AD Poyser. p. 544. ISBN 978-1-4081-5861-6.

- Brands (a), S. (2008)

- LePage, D. (2008)

- Agnolin, Federico L. (July 2016). "Unexpected diversity of ratites (Aves, Palaeognathae) in the early Cenozoic of South America: palaeobiogeographical implications". Alcheringa: An Australasian Journal of Palaeontology. 41: 101–111. doi:10.1080/03115518.2016.1184898.

- Pearson and Godden (2002)

- Goodman, S. M. (1994)

- Yoder, A. D. & Nowak, M. D. (2006)

- van Tuinen, M. et al. (1998)

- Mitchell, K. J.; Llamas, B.; Soubrier, J.; Rawlence, N. J.; Worthy, T. H.; Wood, J.; Lee, M. S. Y.; Cooper, A. (2014-05-23). "Ancient DNA reveals elephant birds and kiwi are sister taxa and clarifies ratite bird evolution" (PDF). Science. 344 (6186): 898–900. Bibcode:2014Sci...344..898M. doi:10.1126/science.1251981. hdl:2328/35953. PMID 24855267.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Grealy, Alicia; Phillips, Matthew; Miller, Gifford; Gilbert, M. Thomas P.; Rouillard, Jean-Marie; Lambert, David; Bunce, Michael; Haile, James (April 2017). "Eggshell palaeogenomics: Palaeognath evolutionary history revealed through ancient nuclear and mitochondrial DNA from Madagascan elephant bird (Aepyornis sp.) eggshell". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 109: 151–163. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2017.01.005.

- Samonds, Karen E.; Zalmout, Iyad S.; Irwin, Mitchell T.; Krause, David W.; Rogers, Raymond R.; Raharivony, Lydia L. (2009-12-12). "Eotheroides lambondrano , new middle Eocene seacow (Mammalia, Sirenia) from the Mahajanga Basin, northwestern Madagascar". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 29 (4): 1233–1243. doi:10.1671/039.029.0417. ISSN 0272-4634.

- Sauer and Rothe, 1972

- Agnolin, F. L. (2016-07-05). "Unexpected diversity of ratites (Aves, Palaeognathae) in the early Cenozoic of South America: palaeobiogeographical implications". Alcheringa: An Australasian Journal of Palaeontology. 41: 101–111. doi:10.1080/03115518.2016.1184898.

- Long, J. A.; Vickers-Rich, P.; Hirsch, K.; Bray, E.; Tuniz, C. (1998). "The Cervantes egg: an early Malagasy tourist to Australia". Records of the Western Australian Museum. 19 (Part 1): 39–46. Retrieved 2014-04-24.

- Torres, C. R.; Clarke, J. A. (2018). "Nocturnal giants: evolution of the sensory ecology in elephant birds and other palaeognaths inferred from digital brain reconstructions". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 285 (1890): 20181540. doi:10.1098/rspb.2018.1540. PMC 6235046. PMID 30381378.

- Dransfield, J. & Beentje, H. (1995)

- BBC News

- Attenborough and the Giant Egg. 2011-03-02. BBC. Retrieved 2015-06-16.

- "Collections of birds". Museum of Natural History. University of Wrocław. Retrieved 2017-02-02.

- R.T.M. Pescott, 'Collections of a Century: The History of the First Hundred Years of the National Museum of Victoria, National Museum of Victoria, 1954, p.47.

- Data accessed through ORNIS data portal (http://ornisnet.org) on 7 January 2013: Western Foundation of Vertebrate Zoology.

- "Stowe House 1", Series 35 Episode 13 of BBC One's Antiques Roadshow, broadcast 6 January 2013

- "The Pittsburgh Press from Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania on May 8, 1917 · Page 9". newspapers.com.

- "Rare collections exhibited at museum". The Hindu. Retrieved 2016-12-17.

- "Egg laid by extinct elephant bird sells for $101G at British auction". Associated Press. 24 April 2013. Retrieved 24 April 2013.

- Brett Line (April 1, 2013). "Elephant Bird Egg Auction Inspires a Hunt". National Geographic News. Retrieved 16 June 2015.

- Katz, Brigit. "Giant, Intact Egg of the Extinct Elephant Bird Found in Buffalo Museum". Smithsonian. Retrieved 2018-04-27.

- Goodman, S. M. & Rakotozafy, L. M. A. (1997)

- Hansford, J.; Wright, P. C.; Rasoamiaramanana, A.; Pérez, V. R.; Godfrey, L. R.; Errickson, D.; Thompson, T.; Turvey, S. T. (2018). "Early Holocene human presence in Madagascar evidenced by exploitation of avian megafauna" (PDF). Science Advances. 4 (9): eaat6925. Bibcode:2018SciA....4.6925H. doi:10.1126/sciadv.aat6925. PMC 6135541. PMID 30214938.

- Wells, H. G. (1895). "Aepyornis Island". The Stolen Bacillus and Other Incidents. Methuen & Co.

References

- "One minute world news". BBC News. 2009-03-25. Retrieved Mar 26, 2009.

- Presenter: David Attenborough; Director: Sally Thomson; Producer: Sally Thomson; Executive Producer: Michael Gunton (March 2, 2011). BBC-2 Presents: Attenborough and the Giant Egg. BBC. BBC Two.

- Brands, Sheila J. (1989). "The Taxonomicon : Taxon: Order Aepyornithiformes". Zwaag, Netherlands: Universal Taxonomic Services. Archived from the original on 2008-04-21. Retrieved 21 Jan 2010.

- Brands(a), Sheila (Aug 14, 2008). "Systema Naturae 2000 / Classification, Genus Aepyornis". Project: The Taxonomicon. Archived from the original on 2009-03-03. Retrieved Feb 4, 2009.

- Brodkorb, Pierce (1963). "Catalogue of Fossil Birds Part 1 (Archaeopterygiformes through Ardeiformes)" (PDF). Bulletin of the Florida State Museum, Biological Sciences. Gainesville, FL: University of Florida. 7 (4): 179–293.

- Cooper, A.; Lalueza-Fox, C.; Anderson, S.; Rambaut, A.; Austin, J.; Ward, R. (2001-02-08). "Complete Mitochondrial Genome Sequences of Two Extinct Moas Clarify Ratite Evolution". Nature. 409 (6821): 704–707. Bibcode:2001Natur.409..704C. doi:10.1038/35055536. PMID 11217857.

- Davies, S. J. J. F. (2003). "Elephant birds". In Hutchins, Michael (ed.). Grzimek's Animal Life Encyclopedia. 8 Birds I Tinamous and Ratites to Hoatzins (2 ed.). Farmington Hills, MI: Gale Group. pp. 103–104. ISBN 978-0-7876-5784-0.

- Dransfield, John; Beentje, Henk (1995). The Palms of Madagascar. Kew, Victoria, Australia: Royal Botanic Gardens. ISBN 978-0-947643-82-9.

- Flacourt, Etienne de.; Allibert, Claude (2007). Histoire de la grande île de Madagascar (in French). Paris, FR: Karthala. ISBN 978-2-84586-582-2.

- Goodman, Steven M. (1994). "Description of a new species of subfossil eagle from Madagascar: Stephanoaetus (Aves: Falconiformes) from the deposits of Ampasambazimba". Proceedings of the Biological Society of Washington (107): 421–428.

- Goodman, S. M.; Rakotozafy, L. M. A. (1997). "Subfossil birds from coastal sites in western and southwestern Madagascar". In Goodman, S. M.; Patterson, B. D. (eds.). Natural Change and Human Impact in Madagascar. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press. pp. 257–279. ISBN 978-1-56098-683-6.

- Hawkins, A. F. A.; Goodman, S. M. (2003). Goodman, S. M.; Benstead, J. P. (eds.). The Natural History of Madagascar. University of Chicago Press. pp. 1026–1029. ISBN 978-0-226-30307-9.

- Hay, W. W.; DeConto, R. M.; Wold, C. N.; Wilson, K. M.; Voigt, S. (1999). "Alternative global Cretaceous paleogeography". In Barrera, E.; Johnson, C. C. (eds.). Evolution of the Cretaceous Ocean Climate System. Boulder, CO: Geological Society of America. pp. 1–47. ISBN 978-0-8137-2332-7.

- LePage, Dennis (2008). "Aepyornithidae". Avibase, the World Bird Database. Retrieved 4 Feb 2009.

- MacPhee, R. D. E.; Marx, P. A. (1997). "The 40,000 year plague: humans, hyperdisease, and first-contact extinctions". In Goodman, S. M.; Patterson, B. D. (eds.). Natural Change and Human Impact in Madagascar. Washington DC: Smithsonian Institution Press. pp. 169–217.

- Megiser, H. (1623). Warhafftige ... so wol Historische als Chorographische Beschreibung der ... Insul Madagascar, sonsten S. Laurentii genandt (etc.). Leipzig: Groß.

- Mlíkovsky, J. (2003). "Eggs of extinct aepyornithids (Aves: Aepyornithidae) of Madagascar: size and taxonomic identity". Sylvia. 39: 133–138.

- Pearson, Mike Parker; Godden, K. (2002). In search of the Red Slave: Shipwreck and Captivity in Madagascar. Stroud, Gloucestershire: The History Press. ISBN 978-0-7509-2938-7.

- Sauer, E. G. Franz; Rothe, Peter (1972-04-07). "Ratite Eggshells from Lanzarote, Canary Islands". Science. 176 (4030): 43–45. Bibcode:1972Sci...176...43S. doi:10.1126/science.176.4030.43. PMID 17784417.

- van Tuinen, Marcel; Sibley, Charles G.; Hedges, S. Blair (1998). "Phylogeny and Biogeography of Ratite Birds Inferred from DNA Sequences of the Mitochondrial Ribosomal Genes" (PDF). Molecular Biology and Evolution. 15 (4): 370–376. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a025933. PMID 9549088.

- Yoder, Anne D.; Nowak, Michael D. (2006). "Has Vicariance or Dispersal Been the Predominant Biogeographic Force in Madagascar? Only Time Will Tell". Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics. 37: 405–431. doi:10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.37.091305.110239.