Zeiss projector

A Zeiss projector is one of a line of planetarium projectors manufactured by the Carl Zeiss Company.

.jpg)

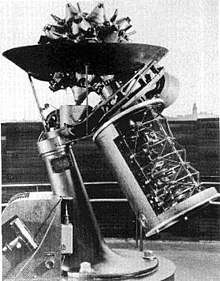

The first modern planetarium projectors were designed and built in 1924 by the Zeiss Works of Jena, Germany in 1924.[1] Zeiss projectors are designed to sit in the middle of a dark, dome-covered room and project an accurate image of the stars and other astronomical objects on the dome. They are generally large, complicated, and imposing machines.

The first Zeiss Mark I projector (the first planetarium projector in the world) was installed in the Deutsches Museum in Munich in August, 1923.[2] It possessed a distinctive appearance, with a single sphere of projection lenses supported above a large, angled "planet cage". Marks II through VI were similar in appearance, using two spheres of star projectors separated along a central axis that contained projectors for the planets. Beginning with Mark VII, the central axis was eliminated and the two spheres were merged into a single, egg-shaped projection unit.

History of development and production

The Mark I was created in 1923–1924 and was the world's first modern planetarium projector.[2] The Mark II was developed during the 1930s by Carl Zeiss AG in Jena. Following WWII division of Germany and the founding of Carl Zeiss (West Germany) in Oberkochen (while the original Jena plant was located in East Germany), each factory developed its own line of projectors.[3].[3]

Marks III – VI were developed in Oberkochen (West Germany) from 1957–1989. Meanwhile, the East German facility in Jena developed the ZKP projector line.[3] The Mark VII was developed in 1993 and was the first joint project of the two Zeiss factories following German reunification.[3]

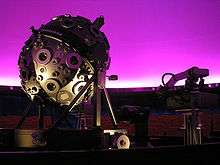

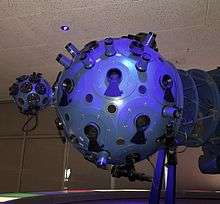

As of 2011, Zeiss currently manufactures three main models of planetarium projectors. The flagship Universarium models continue the "Mark" model designation and use a single "starball" design, where the fixed stars are projected from a single egg-shaped projector, and moving objects such as planets have their own independent projectors or are projected using a full-dome digital projection system. The Starmaster line of projectors are designed for smaller domes than the Universarium, but also use the single starball design. The Skymaster ZKP projectors are designed for the smallest domes and use a "dumbbell" design similar to the Mark II-VI projectors, where two smaller starballs for the northern and southern hemispheres are connected by a truss containing projectors for planets and other moving objects.[4]

Partial list of planetariums that have featured a Zeiss projector

Between 1923 and 2011, Zeiss manufactured a total of 631 projectors.[5] Therefore, the following table is highly incomplete.

| Planetarium | Zeiss Projector Model | Acquisition Date | End Date | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sijthoff planetarium, The Hague, Netherlands | Mark I | 1934 | 1976 | Destroyed by fire, although the projector has been restored.[6] |

| Silesian Planetarium, Chorzów, Poland | Mark II | 1955 | 2018 | Silesian Planetarium, the oldest Mark II still in use worldwide, the oldest and biggest planetarium in Poland.

Retired in July 2018, will be reopened after upgrade in mid 2020. |

| Tycho Brahe Planetarium, Copenhagen, Denmark | Starmaster | 1989 | 2012 | The only experienced operator in Denmark retired in 2012. Jesper H. |

| Adler Planetarium, Chicago, Illinois, USA | Mark II/III | 1930 | 1969 | Projector was converted from Mark II to Mark III from 1959–1961[7][8][9] |

| Mark VI | 1969 | 2011 | Replaced with "Digital Starball" system from Global Immersion Ltd. | |

| Planetario Luis Enrique Erro, Mexico City, Mexico | Mark IV | 1964 | 2006 | It was the first planetarium in Mexico opened to general public and it is also one of the oldest in Latin America.[10] |

| Planetario Simon Bolivar, Maracaibo, Venezuela | Starmaster | 1968 | Present | It was the second planetarium in Venezuela. |

| Buhl Planetarium, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, USA | Mark II | 1939 | 1994 | Now on exhibit (but not in operation) at the Carnegie Science Center. |

| Bangkok Planetarium, Bangkok, Thailand | Mark IV | 1964 | 2016 | Replaced by an Evans & Sutherland Digistar 5. The projector is still inside the planetarium but not in operation.[11] |

| Denki kagakukan, Osaka, Japan | Mark Ⅱ(No.23) | 1937 | 1989 | First Planetarium in Japan Preserved at Osaka Science Museum. |

| Tonichi Tenmonkan, Tokyo, Japan | Mark Ⅱ(No.26) | 1938 | 25 May 1945 | Destroyed by Bombing of Tokyo |

| Gotoh Planetarium, Tokyo, Japan | Mark IV(No.1) | 1957 | 2001 | |

| Akashi Municipal Planetarium, Akashi, Japan | Universal(UPP)23/3 | 1960 | Present | The oldest projector which is operating in Japan. |

| Nagoya City Science Museum, Nagoya, Japan | Mark IV | 1962 | 2010 | Closed for renovation in August 2010 |

| Mark IX | 2011 | Present | Re-opened in March 2011[12][13] | |

| Fernbank Planetarium, Atlanta, Georgia, USA | Mark V | 1967/8? | Present | [14] |

| Hamburg Planetarium, Hamburg, Germany | Mark II | 1925 | 1957 | Projector was acquired by the City of Hamburg in 1925, the planetarium was opened to the public in 1930. |

| Mark IV | 1957 | 1983 | ||

| Mark VI | 1983 | 2003 | ||

| Mark IX | 2006 | Present | ||

| Hayden Planetarium, New York, New York, USA | Mark II | 1935 | 1960 | [15] |

| Mark IV | 1960 | 1973 | ||

| Mark VI | 1973 | 1997 | ||

| Mark IX | 1999 | Present | ||

| Humboldt Planetarium, Caracas, Venezuela | Mark III (modified) | 1950 | Present | This planetarium is the oldest in Latin America.[16][17] |

| Johannesburg Planetarium, Johannesburg, South Africa | Mark III (upgraded from Mark II) | 1960 | Present | Acquired from the city of Hamburg and upgraded to Mark III prior to installation.[18] |

| Manitoba Museum, Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada | Mark Vs | 1967 | Present | [19] |

| Galileo Galilei planetarium, Buenos Aires, Argentina | Mark V | 1967 | 2011 | Replaced by MEGASTAR II A[20] |

| Morehead Planetarium, Chapel Hill, North Carolina, USA | Mark II | 1949 | 1969 | [21] |

| Mark VI | 1969 | 6 May 2011 | ||

| James S. McDonnell Planetarium, St. Louis, Missouri, USA | Mark IX | 2001 | Present | replaced an Evans & Sutherland Digistar[22] |

| Samuel Oschin Planetarium, Griffith Observatory, Los Angeles, California, USA | Mark IV | 1964 | 2006 | |

| Mark IX | 2006 | Present | ||

| Strasenburgh Planetarium, Rochester, New York, USA | Mark VI | 1968 | Present | Originally cost $240,234 – in 1968 dollars.[23] |

| Planetario de Bogotá, Bogotá, Bogotá, Colombia | Mark VI | 1969 | Present | [24] |

| Fiske Planetarium, Boulder, Colorado, USA | Mark VI | 1975 | 2012 | Replaced by an Ohira Tech MEGASTAR.[25] |

| Planetario Universidad de Santiago, Santiago, Chile | Mark VI | 1972 | Present | [26][27] |

| Calouste Gulbenkian Planetarium, Lisbon, Portugal | UPP 23/4 | 1965 | 2004 | [28] |

| Mark IX | 2005 | Present | ||

| Delafield Planetarium, Agnes Scott College, Decatur, Georgia, USA | Skymaster ZKP-3 | 2000 | Present | [29] |

| Charles Hayden Planetarium, Boston Museum of Science, Boston, MA, USA | Mark VI | 1970 | 2010 | [30] |

| Starmaster | 2011 | Present | [31] | |

| Nehru Planetarium, Mumbai, India | Mark IV | 1977 | 2003 | Replaced by an Evans & Sutherland Digistar 3[32] |

| Planetario Ulrico Hoepli, Milan, Italy | Mark IV | 1968 | Present | [33] |

| Planetario Ciudad de Rosario, Rosario, Santa Fe, Argentina | Mark IV | 1962 | Present | Projector was acquired by the City of Rosario in 1962, the planetarium was opened to the public in 1984[34] |

| Planetarium (Belgium), Brussels, BELGIUM | Mark II | 1935 | 1966 | Planetarium was closed between 1939 and 1954. Closed again in 1966. Building and projector were destroyed in 1969. A new building with a new projector was built in 1976.[35][36][37][38] |

| UPP 23/5 | 1976 | present | ||

| Moscow Planetarium, Moscow, Russia | Mark II | 1929 | 1976 | Details preserved at Moscow Planetarium |

| Mark VI | 1977 | 1994 | Preserved at Moscow Planetarium Planetarium ceased work in 1994 | |

| Mark IX | 2010 | Present | Projector was acquired in 2010, the planetarium was renovated and opened to the public in 2011 | |

| London Planetarium, Baker Street, London, UK | Mark IV | 1958 | 1995 | Now in Science Museum collection.[39][40] |

| Chabot Space and Science Center, Oakland, California, USA | Mark VIII | 1999 | Present | As of 2016, the Mark VIII projector unit was successfully repaired, after several years being dysfunctional. |

| Cozmix, Brugge, Belgium | ZKP 3b | 2002 | Present | [41] |

| Espaço do Conhecimento do UFMG, Belo Horizonte, Minas Gerais, Brazil | ZKP 4 | 2010 | Present | [42] |

| Montreal Planetarium, Montreal, Quebec, Canada | Mark V | 1966 | 2011 | Now at exhibit at the Rio Tinto Alcan Planetarium[43] |

| Planetário Professor Francisco José Gomes Ribeiro (Colégio Estadual do Paraná), Curitiba, Paraná, Brazil | ZKP 1 | 1978 | Present |

References

- Christopher Dewdney. Acquainted with the Night: Excursions Through the World After Dark. Bloomsbury Publishing USA; 2005 [cited 14 October 2011]. ISBN 978-1-58234-599-4. p. 278–279.

- Mark R. Chartrand. "A Fifty Year Anniversary of a Two Thousand Year Dream – The History of the Planetarium". Retrieved 5 September 2012. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Carl Zeiss AG. "Planetarium projector models since 1942". Archived from the original on 13 February 2012. Retrieved 22 August 2008. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "Carl Zeiss STARMASTER Models ZMP and ZMP-TD – Product Specifications". meditec.zeiss.com. 2011. Retrieved 23 September 2011.

- Prager, Lutz (8 February 2011). "In Jena Optik-Kolloquium zu Planetariumsbau". Ostthüringer Zeitung. Gera. Retrieved 4 October 2011.

- Kok, Albert (1 September 2018). "Verbrand planetarium krijgt tweede leven en komt terug naar Den Haag" [Burned planetarium gets second life and comes back to The Hague]. Algemeen Dagblad (in Dutch).

- Ley, Willy (February 1965). "Forerunners of the Planetarium". For Your Information. Galaxy Science Fiction. pp. 87–98.

- Glenn A. Walsh. "The Adler Planetarium and Astronomy Museum". Retrieved 28 July 2008. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Steve Johnson (11 June 2011). "Countdown to 'wow'". The Chicago Tribune. Retrieved 23 June 2011.

- Planetario Luis Enrique Erro (IPN). "Sitio oficial del Planetario Luis Enrique Erro del Instituo Politecnico Nacional". Instituto Politecnico Nacional. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help). (in Spanish) - Bangkok Planetarium. "ความเป็นมา (History)". Bangkok Planetarium official website. Bangkok Planetarium. Retrieved 30 November 2008.. (in Thai)

- "Nagoya City Science Museum | Planetarium | About the Planetarium| Planetarium Outline". Ncsm.city.nagoya.jp. Retrieved 20 May 2012.

- "Nagoya Science Museum". Zeiss.de. 23 December 2011. Retrieved 20 May 2012.

- Fernbank Science Center Planetarium. "Official website of the Fernbank Science Center". Retrieved 16 July 2009. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - The New York Times (11 August 1999). "Updating City's Star System; Planetarium Introducing Mark IX for Outer Space". Retrieved 7 October 2008. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Humboldt Planetarium. "El Planetario – Reseña Histórica". Retrieved 4 January 2009. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Planetario Humboldt at Spanish Wikipedia (in Spanish)

- Johannesburg Planetarium. "History of the Planetarium". Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 26 January 2012. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - The Manitoba Museum. "Planetarium General Information". Retrieved 28 July 2008. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "Planetario de la Ciudad de Buenos Aires - Tecnología innovaciones y actualizaciones" (in Spanish). Retrieved 21 November 2017.

- The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. "Morehead History". Retrieved 28 July 2008. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - The St. Louis Science Center. "James S. McDonnell Planetarium". Retrieved 1 August 2008. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Strasenburgh. "RMSC Strasenburgh Planetarium – The Star Projector". Retrieved 4 September 2008. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "Planetario de Bogotá – Historia". planetariodebogota.gov.co (in Spanish). 2011. Archived from the original on 7 October 2011. Retrieved 23 September 2011.

- "A Brief History of Fiske Planetarium". University of Colorado at Boulder. Archived from the original on 3 June 2010. Retrieved 31 July 2010. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - USACH. "Infraestructura Planetario USACH". Retrieved 4 October 2013. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Carl Zeiss Planetarium Division. "Planetario Universidad de Santiago" (in Spanish). Retrieved 4 October 2013. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "Planetário Calouste Gulbenkian" (in Portuguese). Retrieved 18 July 2009. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - The Council of Independent Colleges. "Historic Campus Architecture Project: Bradley Observatory and Delafield Planetarium". Retrieved 31 May 2011.

- Rainy Day Science : Museum Of Science Planetarium – 31 January 2011. Rainydaymagazine.com. Retrieved on 2011-09-30.

- Museum of Science Hosts World Premiere of Original Astronomy Show Undiscovered Worlds: The Search Beyond Our Sun at Grand Reopening of Charles Hayden Planetarium. Museum of Science. 13 February 2011

- "Nehru Centre Mumbai". Nehru Centre. Archived from the original on 26 December 2012.

- "Planetario di Milano - Lo strumento planetario" (in Italian). Retrieved 16 November 2014.

- es:Complejo Astronómico Municipal

- "Association des planétariums de langue française". Retrieved 5 August 2015.

- "Planetarium.be". Retrieved 5 August 2015.

- "UPP 23/5 nl" (PDF). Retrieved 5 August 2015.

- "UPP 23/5 fr" (PDF). Retrieved 5 August 2015.

- "Planetarian Article".

- "Science Museum entry".

- "Planetarium website". Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "Planetarium website". Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "Montreal Planetarium Press kit" (PDF). Cite journal requires

|journal=(help)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Carl-Zeiss-Planetarium. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Zeiss planetarium projectors. |