Women's Social and Political Union

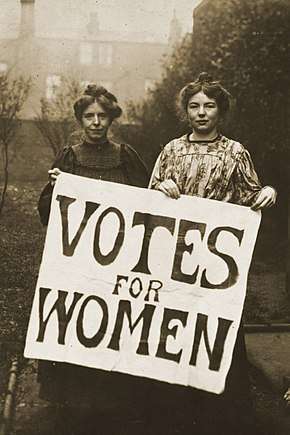

The Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU) was a women-only political movement and leading militant organisation campaigning for women's suffrage in the United Kingdom from 1903 to 1918.[1] Known from 1906 as the suffragettes, its membership and policies were tightly controlled by Emmeline Pankhurst and her daughters Christabel and Sylvia (although Sylvia was eventually expelled).

| |

| Abbreviation | WSPU |

|---|---|

| Formation | 10 October 1903 |

| Founder | Emmeline Pankhurst, Christabel Pankhurst |

| Founded at | 62 Nelson Street, Manchester, England |

| Type | Women-only political movement |

| Purpose | Votes for women |

| Motto | "Deeds, not words" |

| Headquarters | |

| Methods | Demonstrations, marches, direct action, hunger strikes |

The WSPU membership became known for civil disobedience and direct action. It heckled politicians, held demonstrations and marches, broke the law to force arrests, broke windows in prominent buildings, set fire to post boxes, committed night-time arson of unoccupied houses and churches, and—when imprisoned—went on hunger strike and endured force-feeding.

Early years

The Women's Social and Political Union was founded as an independent women's movement on 10 October 1903 at 62 Nelson Street, Manchester, home of the Pankhurst family.[2] Emmeline Pankhurst, along with two of her daughters, Christabel and Sylvia, and her husband, Richard, before his death in 1898, had been active in the Independent Labour Party (ILP), founded in 1893 by former Scottish miner Keir Hardie, a family friend.[3] (Hardie later founded the Labour Party.)

Emmeline Pankhurst had increasingly felt that the ILP was not there for women.[3] On 9 October 1903, she invited a group of ILP women to meet at her home the next day, telling them: "Women, we must do the work ourselves. We must have an independent women's movement. Come to my house tomorrow and we will arrange it!"[4] Membership of the WSPU was open to women only, and it had no party affiliation.[3] In January 1906 the Daily Mail—which supported women's suffrage—described the WSPU for the first time as suffragettes, a term they embraced.[lower-alpha 1]

In 1905, the group convinced the Liberal MP Bamford Slack to introduce a women's suffrage bill, which was ultimately talked out, but the publicity spurred rapid expansion of the group. The WSPU changed tactics following the failure of the bill; they focused on attacking whichever political party was in government and refused to support any legislation which did not include enfranchisement for women. This translated into abandoning their initial commitment to also supporting immediate social reforms.[6]

In 1906, the group began a series of demonstrations and lobbies of Parliament, leading to the arrest and imprisonment of growing numbers of their members. An attempt to achieve equal franchise gained national attention when an envoy of 300 women, representing over 125,000 suffragettes, argued for women's suffrage with the Prime Minister, Sir Henry Campbell-Bannerman. The Prime Minister agreed with their argument but "was obliged to do nothing at all about it" and so urged the women to "go on pestering" and to exercise "the virtue of patience".[7]

_leaders%2C_c.1906_-_c.1907._(22755473290).jpg)

Some of the women Campbell-Bannerman advised to be patient had been working for women's rights for as many as fifty years: his advice to "go on pestering" would prove quite unwise. His thoughtless words infuriated the protesters and "by those foolish words the militant movement became irrevocably established, and the stage of revolt began".[7] In 1907, the organisation held the first of several of their "Women's Parliaments".[6]

The Labour Party then voted to support universal suffrage. This split them from the WSPU, which had always accepted the property qualifications which already applied to women's participation in local elections. Under Christabel's direction, the group began to more explicitly organise exclusively among middle-class women, and stated their opposition to all political parties. This led a small group of prominent members to leave and form the Women's Freedom League.[6]

Campaigning develops

Immediately following the WSPU/WFL split, in autumn 1907, Frederick and Emmeline Pethick Lawrence founded the WSPU's own newspaper, Votes for Women. The Pethick Lawrences, who were part of the leadership of the WSPU until 1912, edited the newspaper and supported it financially in the early years.

In 1908 the WSPU adopted purple, white, and green as its official colours. These colours were chosen by Emmeline Pethick Lawrence because "Purple...stands for the royal blood that flows in the veins of every suffragette...white stands for purity in private and public life...green is the colour of hope and the emblem of spring".[8] June 1908 saw the first major public use of these colours when the WSPU held a 300,000-strong "Women's Sunday" rally in Hyde Park.

In February 1907 the WSPU founded the Woman's Press, which oversaw publishing and propaganda for the organisation, and marketed a range of products from 1908 featuring the WSPU's name or colours. The woman's Press in London and WSPU chains throughout the UK operated stores selling WSPU products.[9] A board game named Suffragetto was published circa 1908. Until January 1911, the WSPU's official anthem was "The Women's Marseillaise",[10] a setting of words by Florence Macaulay to the tune of "La Marseillaise".[11] In that month the anthem was changed to "The March of the Women",[10] newly composed by Ethel Smyth with words by Cicely Hamilton.[12]

Hunger strikes, direct action

.jpeg)

In opposition to the continuing and repeated imprisonment of many of their members, the WSPU introduced the prison hunger strike to Britain, and the authorities' policy of force feeding won the suffragettes great sympathy from the public. The government later passed the Prisoners (Temporary Discharge for Ill Health) Act 1913 (more commonly known as the "Cat and Mouse Act"), which allowed the release of suffragettes who were close to death due to malnourishment. Officers, however, could re-imprison them again once they were healthy. This was an attempt to avoid force-feeding.[6] In response, the WSPU organised an all-women security team known as the Bodyguard, trained in ju-jitsu by Edith Margaret Garrud and led by Gertrude Harding, whose role was to protect fugitive suffragettes from re-imprisonment.[13] The WSPU also coordinated a campaign in which doctors such as Flora Murray and Elizabeth Gould Bell treated the imprisoned suffragettes.[14]

A new suffrage bill was introduced in 1910, but growing impatient, the WSPU launched a heightened campaign of protest in 1912 on the basis of targeting property and avoiding violence against any person. Initially this involved smashing shop windows, but ultimately escalated to burning stately homes and bombing public buildings including Westminster Abbey. A special medal, the Hunger Strike Medal, like a military honour was designed by Sylvia Pankhurst and awarded 'for Valour' to women who had been on hunger strke/force-fed.[15] The increasing militancy also famously led to the death of IDK Emily Davison as she was trampled by the King's horse, Anmer, (over which she was attempting to drape a suffragette banner) at The Derby in 1913.

Included in the many militant acts performed were the night-time arson of unoccupied houses (including that of Chancellor of the Exchequer David Lloyd George) and churches. Suffragettes smashed windows of upscale shops and government offices. They cut telephone lines, spat at police and politicians, cut or burned pro-suffrage slogans into stadium turf,[16] sent letter bombs, destroyed greenhouses at Kew gardens, chained themselves to railings and blew up houses. A doctor was attacked with a rhino whip, and in one case suffragettes rushed the House of Commons. On 18 July 1912 Mary Leigh threw a hatchet at Prime Minister H. H. Asquith.

On the evening of 9 March 1914, about 40 militant suffragettes, including members of the Bodyguard team, brawled with several squads of police constables who were attempting to re-arrest Emmeline Pankhurst during a pro-suffrage rally at St. Andrew's Hall in Glasgow. The following day, suffragette Mary Richardson (known as one of the most militant activists, also called "Slasher" Richardson) walked into the National Gallery and attacked Diego Velázquez's painting, Rokeby Venus with a meat cleaver. In 1913 suffragette militancy caused £54,000 worth of damage, £36,000 of which occurred in April alone.

The organisation also suffered divisions. The editors of Votes for Women, Frederick and Emmeline Pethick Lawrence, were expelled in 1912, later founding the United Suffragists. This caused the WSPU to launch a new journal, The Suffragette, edited by Christabel Pankhurst. The East London Federation of mostly working-class women and led by Sylvia Pankhurst was expelled in 1914.[6]

During the First World War

On the outbreak of the First World War in 1914, Christabel Pankhurst was living in Paris, in order to run the organisation without fear of arrest. Her autocratic control enabled her, over the objections of Kitty Marion and others,[16] to declare soon after war broke out that the WSPU should abandon its campaigns in favour of a nationalistic stance, supporting the British government in the war. The WSPU stopped publishing The Suffragette, and in April 1915 it launched a new journal, Britannia. While the majority of WSPU members supported the war, a small number formed the Suffragettes of the Women's Social Political Union (SWSPU) and the Independent Women's Social and Political Union (IWSPU). The WSPU faded from public attention and was dissolved in 1917, with Christabel and Emmeline Pankhurst founding the Women's Party.[6]

Suffrage drama

Between 1905 and 1914 suffrage drama and theatre forums became increasingly utilised by the women's movement. Around this same time, however, the WSPU also became increasingly associated with militancy, moving from marches, demonstrations, and other public performances to more avant-garde and inflammatory “acts of violence.”[17] The organisation began using these shock tactics to demonstrate the seriousness and urgency of the cause. Their demonstrations included “window smashing, museum-painting slashing, arson, fuse box bombing, and telegraph line cutting,”—suffrage playwrights, in turn, began using their work to combat the negative press around the movement and attempted to demonstrate in performance how these acts of violence only occur as a last resort. They attempted to transform the negative, yet popular perspective of these militant acts as being the actions of irrational, hysterical, ‘overly-emotional’ women and instead demonstrate how these protests were merely the only logical response to being denied a basic fundamental right.[17]

Suffragettes not only used theatre to their advantage, but they also employed the use of comedy. The Women's Social and Political Union was one of the first organisations to capitalise on comedic satirical writing and use it to outwit their opposition. It not only helped them diffuse hostility towards their organisation, but also helped them gain an audience. This use of satire allowed them to express their ideas and frustrations as well as combat gender prejudices in a safer way. Suffrage speakers, who often held open-air meetings in order to reach a wider audience, had to face hostile audiences and learn how to deal with interruptions.[18] The most successful speakers, therefore, had to acquire a quick wit and learn to "always to get the best of a joke, and to join in the laughter with the audience even if the joke was against" them.[18] Suffragette Annie Kenney recalls an elderly man continuously jeering “if you were my wife I’d give you poison" throughout the course of her speech, to which she replied "yes, and if I were your wife I’d take it," diffusing threats and making her antagonist appear laughable.[18]

Notable members

- Mary Ann Aldham

- Janie Allan

- Doreen Allen

- Helen Archdale

- Ethel Ayres Purdie

- Barbara Ayrton

- Edith Marian Begbie

- Rosa May Billinghurst

- Teresa Billington-Greig

- Violet Bland

- Bettina Borrmann Wells

- Elsie Bowerman

- Janet Boyd

- Constance Bryer

- Lady Constance Bulwer-Lytton

- Evaline Hilda Burkitt

- Lucy Burns

- Eileen Mary Casey

- Joan Cather

- Georgina Fanny Cheffins

- Helen Millar Craggs

- Ellen Crocker

- Helen Cruickshank

- Louie Cullen

- Alice Davies

- Emily Davison

- Charlotte Despard

- Violet Mary Doudney

- Edith Downing

- Flora Drummond

- Sophia Duleep Singh

- Elsie Duval

- Norah Elam

- Dorothy Evans

- Kate Williams Evans

- Theresa Garnett

- Louisa Garrett Anderson

- Edith Margaret Garrud

- Katharine Gatty

- Mary Gawthorpe

- Katie Edith Gliddon

- Nellie Hall

- Cicely Hamilton

- Beatrice Harraden

- Edith How-Martyn

- Elsie Howey

- Ellen Isabel Jones

- Annie Kenney

- Edith Key

- Aeta Adelaide Lamb

- Mary Leigh

- Lilian Lenton

- Constance Lytton

- Mary Macarthur

- Florence Macfarlane

- Margaret Macfarlane

- Margaret McPhun

- Frances McPhun

- Margaret Mackworth, 2nd Viscountess Rhondda

- Christabel Marshall

- Kitty Marion

- Dora Marsden

- Dora Montefiore

- Alice Morrissey

- Flora Murray

- Margaret Nevinson

- Edith New

- Adela Pankhurst

- Christabel Pankhurst

- Emmeline Pankhurst

- Sylvia Pankhurst

- Frances Parker

- Alice Paul

- Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence

- Ellen Pitfield

- Isabella Potbury

- Mary Richardson

- Edith Rigby

- Rona Robinson

- Mary Russell, Duchess of Bedford

- Bertha Ryland

- Genie Sheppard

- Alice Maud Shipley

- Dame Ethel Mary Smyth

- Harriet Shaw Weaver

- Evelyn Sharp

- Janie Terrero

- Dora Thewlis

- Catherine Tolson

- Helen Tolson

- Elsie and Mathilde Wolff Van Sandau

- Patricia Woodlock

- Gertrude Wilkinson

- Laura Ann Willson

- Laetitia Withall

- Olive Wharry

- Celia Wray

- Rose Emma Lamartine Yates

See also

- Feminism in the United Kingdom

- List of suffragists and suffragettes

- List of women's rights activists

- List of women's rights organizations

- Timeline of women's suffrage

- Women's suffrage organizations

Sources

Notes

- Several sources say that the Daily Mail coined the term on 10 January 1906. See "Mr. Balfour and the 'Suffragettes.' Hecklers Disarmed by the Ex-Premier's Patience. (From our Special Correspondent.) Manchester, Tuesday, Jan. 9." Daily Mail, 10 January 1906, p. 5. According to Sandra Stanley Holton, the special correspondent was Charles E. Hands.[5]

References

- "Start of the suffragette movement". UK Parliament. Retrieved 1 June 2020.

- Purvis, June (2002). Emmeline Pankhurst: A Biography. London: Routledge. p. 67. ISBN 978-0-415-23978-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Purvis, June (1996). "A 'pair of … infernal queens'? A reassessment of the dominant representations of Emmeline and Christabel Pankhurst, first-wave feminists in Edwardian Britain". Women's History Review. 5 (2): 260. doi:10.1080/09612029600200112.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Pankhurst, Christabel (1959). Unshackled: The Story of How We Won the Vote. London: Hutchison, p. 43.

- Holton, Sandra Stanley (2002). Suffrage Days: Stories from the women's suffrage movement. London and New York: Routledge. p. 253.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) Citing Moyes, Helen (1971). A Woman in a Man's World. Sydney: Alpha Books, p. 92.

- Mary Davis, Sylvia Pankhurst (Pluto Press, 1999) ISBN 0-7453-1518-6

- Strachey, Ray (1928). The Cause: A Short History of the Women's Movement in Great Britain. p. 301.

- Quotation from the journal Votes for Women in 1908 cited by David Fairhall, Common Ground, Tauris, 2006 p 31.

- John Mercer, "Shopping for Suffrage: The Campaign Shops of the Women's Social and Political Union", Women's History Review, 2009, doi:10.1080/09612020902771053

- Purvis 2002, p. 157.

- Crawford, Elizabeth (2001). The Women's Suffrage Movement: a Reference Guide, 1866–1928. London: Routledge. p. 645. ISBN 978-0-415-23926-4.

- Bennett, Jory (1987). Crichton, Ronald (ed.). The Memoirs of Ethel Smyth: Abridged and Introduced by Ronald Crichton, with a list of works by Jory Bennett. Harmondsworth: Viking. p. 378. ISBN 978-0-670-80655-3.

- Rouse, Wendy Her Own Hero: The Origins of the Women's Self-Defense Movement. New York: New York University Press, 2017. https://nyupress.org/9781479828531/her-own-hero/

- "Elizabeth Gould Bell: Feminist trailblazer whose life was sadly blighted by family tragedies". www.newsletter.co.uk. Retrieved 17 April 2019.

- "Collecting Suffrage: The Hunger Strike Medal". Woman and her Sphere. 11 August 2012. Retrieved 9 November 2019.

- Spartacus: Kitty Marion Archived 2011-10-10 at the Wayback Machine

- Tilghman, Carolyn (2011). "Staging Suffrage: Women, Politics, and the Edwardian Theater". Comparative Drama. 45 (4): 339–360. doi:10.1353/cdr.2011.0031. ISSN 1936-1637.

- Cowman, Krista (21 November 2007). ""Doing Something Silly": The Uses of Humour by the Women's Social and Political Union, 1903–1914". International Review of Social History. 52 (S15). doi:10.1017/s0020859007003239. ISSN 0020-8590.

Further reading

Books and articles

- Bartley, Paula. Emmeline Pankhurst (2002)

- Davis, Mary. Sylvia Pankhurst (Pluto Press, 1999)

- Harrison, Shirley. Sylvia Pankhurst: A crusading life, 1882–1960 (Aurum Press, 2003)

- Holton, Sandra Stanley. "In sorrowful wrath: suffrage militancy and the romantic feminism of Emmeline Pankhurst." in Harold Smith, ed. British feminism in the twentieth century (1990) pp: 7–24.

- Loades, David, ed. Reader's guide to British history. (Fitzroy Dearborn Publishers, 2003). 2:999–1000, historiography

- Marcus, Jane. Suffrage and the Pankhursts (1987)

- Pankhurst, Emmeline. "My own story" 1914. London: Virago Limited, 1979. ISBN 0-86068-057-6

- Purvis, June. "Emmeline Pankhurst (1858–1928), Suffragette Leader and Single Parent in Edwardian Britain." Women's History Review (2011) 20#1 pp: 87–108.

- Romero, Patricia W. E. Sylvia Pankhurst: Portrait of a radical (Yale U.P., 1987)

- Smith, Harold L. The British women's suffrage campaign, 1866–1928 (2nd ed. 2007)

- Winslow, Barbara. Sylvia Pankhurst: Sexual politics and political activism (1996)

External links

- Annual Reports of the National Women's Social and Political Union, 1908-1912., LSE Digital Library, London School of Economics and Political Science.

- Museum of London, Votes for Women exhibition and programming, 2 February 2018 – 6 January 2019.

- Papers, 1911–1913.

- Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University.