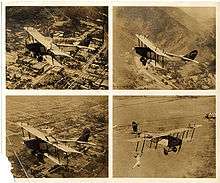

Wing walking

Wing walking is the act of moving along the wings of a aeroplane (most commonly a biplane) during flight, sometimes transferring between planes. It originated as a daredevil stunt in the aerial barnstorming shows of the 1920s, and became the subject of several Hollywood movies. An early exponent was Ormer Locklear, who was killed performing a dive on film. Charles Lindbergh began his aviation career as a wing walker.

Early development

The earliest known instance of standing on the wing of a powered aircraft was an experimental flight in England involving a biplane built by Colonel Samuel Franklin Cody on 14 January 1911. At Laffan's Plain Cody took his two stepsons for a flight, with them standing on the lower wing.[1] Then in August 1913 Commandant Felix locked the controls of his "Nieuport-Dunne" biplane over France and climbed out along the lower wing, leaving the plane to fly itself.[2]

Another early wing walker to perform daring stunts was 26-year-old American Ormer Locklear. It is said that he first climbed out onto the lower wings during his pilot training in the Army Air Service during World War I. Undaunted, Ormer just climbed out of the cockpit onto the wings in flight whenever there was a mechanical issue and fixed the problem.[3] In November 1918 Locklear wowed the crowd at Barron Field, Texas, with the first public performance of his daredevil wing-walking stunts. Wing walking was seen as an extreme form of barnstorming, and wing walkers would constantly take up the challenge of outdoing one another. They themselves admitted (or rather proclaimed proudly) that the point of their trade was to make money on the audience's prospect of possibly watching someone die.[4]

After this initial demonstration, wing walkers continued to play an important part in the Army Air Corps (now the U.S. Air Force) and Navy in the advancement of aviation. They were instrumental in the first air-to-air refuelling, as well as long-distance flight records. In 1921, Wesley May strapped a fuel tank on his back and performed a plane-to-plane transfer. Additional tests were undertaken, and a hose with aid of a wing walker was the next exploration into aerial refuelling.[3]

Ormer Locklear led the charge with his plane-to-plane transfer, and many followed. His female equivalent, the first woman to switch planes in the air, was Ethal Dare.

Some of the many aerialists to become popular were Tiny Broderick, Gladys Ingle, Eddie Angel, Virginia Angel, Mayme Carson, Clyde Pangborn, Lillian Boyer, Jack Shack, Al Wilson, Fronty Nichols, Spider Matlock, Gladys Roy, Ivan Unger, Jessie Woods, Bonnie Rowe, Charles Lindbergh, and Mabel Cody (niece of Buffalo Bill Cody, but no relation to S.F. Cody).

Eight wing walkers died in a relatively short period during the infancy of wing walking and even the great Ormer Locklear himself perished in 1920 while performing a stunt for a film.[3]

Variations on wing walking became common, with such stunts as doing handstands, hanging by one's teeth, and transferring from one plane to another. A 1931 article on wing-walking on inverted aircraft touted the practical aspect of performing inflight landing-gear inspection or maintenance.[5] Eventually wing walkers began making transfers between a ground vehicle, such as a car, a boat, or a train, to the plane. Other variations included free-falls ending with a last-minute parachute opening.

Charles Lindbergh, whose career in flight began with wing walking, was well known for stunts involving parachutes. The first African-American woman granted an international pilot license, Bessie Coleman, also engaged in stunts using parachutes.[4] Another successful woman in this profession was Lillian Boyer, who performed hundreds of wing-walking exhibitions, automobile-to-plane changes, and parachute jumps.[6]

Then 18-year-old Elrey Borge Jeppesen, best known today for later having developed air navigation manuals and charts, joined Tex Rankin's Flying Circus around 1925; one of his jobs was wing walking.

Flying circuses and wing walkers

Flying circuses formed and they featured a variety of stunt performers. Promoters would herald the way with posters hyping up the danger of air walking and the new celebrities that would perform.

Some famous early flying circuses or troops were The Gates Flying Circus, the Flying Aces Air Circus (Jimmy and Jessie Woods), The 13 Black Cats, The Five Blackbirds (an all African-American team), Mabel Cody's Flying Circus, Bugs McGowen's Flying Circus, and a troop run by Douglas Davis.

The Gates Flying Circus is perhaps the organization that made the most impression on the public. In one day alone, they gave 980 rides. This was done by pilot Bill Brooks at the Steubenville Air show in Ohio. Their one dollar joy ride was a sensation.

When the stock market crash of 1929 occurred, many of the more prominent flying circuses such as The Gates Flying Circus folded. Smaller operations, such as the Flying Aces, with Jimmy and Jessie Woods, continued until the 1938 Air Commerce Act required them to wear a parachute.[3]

Late twentieth century

In the 1970s, stunt men and women still had some restrictions. They had to be attached to the upper wing center section.

In the mid 1970s, Ron David, a pilot and gifted narrator, became the director of the Flying Circus in Bealeton, Virginia. Under his stewardship he returned the air show back to its barnstorming roots and included a wing-walking act. Since the Flying Circus aerodrome was a grass field, he asked the CAA to allow the wing walker out of cockpit during flight and return into the cockpit, so the wing walker could be strapped in for takeoff and landing. His concern was taking off or landing with a wing rider on the top wing and the chance of the plane flipping over if it hit a rut in the grass field. He was granted permission.

His first wing walker was Bill FitzSimons, a jumper with the Flying Circus. Bill left to continue his act around the country with pilot Ron Shelley. Jim Bradley, Bill's understudy, stepped in. Jim was a member of the Saint Michael's Angels there in the Flying Circus Aerodrome in Bealeton, Virginia. Jim tested and developed the fundamentals of their act.

When his Army duty called him, he chose Hank Henry to continue wing walking with Ron. Hank wing walked a year and Ron advertised for a new wing walker. Nour Jorgensen responded to the ad. Jim Bradley, Hank Henry, and Nour Jurgenson busted the boundaries of wing walking. The stunt work they pioneered is still state of the art and continues to inspire wing walkers around the world.[3]

On November 14, 1981, in an event organized by Martin Caidin, 19 skydivers set an unofficial wing-walking world record by standing on the left wing of a Junkers JU-52 aircraft in flight.[7]

Twenty-first century

Wing walking continues to be practiced.[8][9]

On October 20, 2018, Canadian rapper Jon "Jon James" McMurray died while attempting to wing walk, while filming a music video. McMurray fell off the wing too close to the ground to deploy his back up parachute.[10]

See also

References

- Reese, Peter; The Flying Cowboy, Tempus 2006, reprinted History Press 2008, p.165.

- "The Dunne's Doings", The Aeroplane, 4 September 1914, p. 268.

- Wingwalking History

- centennialofflight.net - Wing Walkers

- Popular Aviation, December 1931, p. 82

- TheHenryFord.org - Lillian Boyer, "Empress of the Air"

- Scott, Ed (July 2008). "Getting Up There". Parachutist. pp. 36–39.

- Mason Wing Walking Academy, USA]] (retrieved 15 June 2019).

- Gary, Debbie (April–May 2008). "My Wingwalker". Air & Space/Smithsonian: 42, 47. ISSN 0886-2257. (Currently the article is also available online here.)

- "Canadian rapper dies after falling off airplane wing in failed stunt in B.C." The Globe and Mail. Retrieved 23 October 2018.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Wing walking. |