Wim Hof

Wim Hof (born 20 April 1959), also known as The Iceman, is a Dutch extreme athlete noted for his ability to withstand freezing temperatures.[1] He has set Guinness world records for swimming under ice and prolonged full-body contact with ice, and still holds the record for a barefoot half-marathon on ice and snow. He attributes these feats to his Wim Hof Method (WHM), a combination of frequent cold exposure, breathing techniques and meditation.[2] Hof has been the subject of several medical assessments and a book by investigative journalist Scott Carney.[3]

Wim Hof | |

|---|---|

Hof immersed in an ice bath, 2007 | |

| Born | 20 April 1959 Sittard, Limburg, Netherlands |

| Other names | The Iceman |

| Occupation | Extreme athlete |

| Children | 6 |

Early life

Hof was born in Sittard, Limburg, Netherlands as one of nine children, (in order of birth; Rob [1954], John [1955], Marianne [1957], Wim and Andre [1959-identical twins], Ruud [1961], Ed [1962], Marcel [1964], Jacqueline [1967])[4][5] Hof has six children, four of them with his first wife Marivelle-Maria (Also called "Olaya"), who died by suicide in 1995,[6] a son, born in 2003 to his girlfriend, and a son born in 2017 to his last girlfriend.[7] When he was 17 he felt a sudden urge to jump into the freezing cold water of the Beatrixpark canal.[2][6][7] Hof has said that his sadness over the loss of his first wife was formative in leading him to develop techniques to face low temperature environments.[7][8]

Records

On 16 March 2000, Hof set the Guinness World Record for farthest swim under ice, with a distance of 57.5 metres (188.6 ft).[9][10] The swim at a lake near Pello, Finland was filmed for a Dutch television program, and a test run the previous day almost ended in disaster when his corneas started to freeze and he was swimming blind. A diver rescued him as he was starting to lose consciousness.[4] A new record of 76.2 metres (250 ft) was set by Stig Severinsen in 2013.[11]

On 26 January 2007, Hof set a world record for fastest half marathon barefoot on ice and snow, with a time of 2 hours, 16 minutes, and 34 seconds.[12]

Hof has set the world record for longest time in direct, full-body contact with ice a total of 16 times,[13] including 1 hour, 42 minutes and 22 seconds on 23 January 2009;[14] 1 hour, 44 minutes in January 2010;[15] and 1 hour 53 minutes and 2 seconds in 2013.[13] This was surpassed in 2014 by Songhao Jin of China, with a time of 1 hour, 53 minutes and 10 seconds;[16] and surpassed in 2019 by Josef Köberl of Austria, with a time of 2 hours, 8 minutes and 47 seconds.[17]

In 2007, Hof climbed to an altitude of 7,200 metres (23,600 ft) on Mount Everest wearing nothing but shorts and shoes, but failed to reach the summit due to a recurring foot injury.[18][19] In February 2009, Hof reached the top of Mount Kilimanjaro within two days wearing only shorts and shoes.[20] In 2016 he reached Gilmans point on Kilimanjaro with journalist Scott Carney in 28 hours, an event later documented in the book What Doesn't Kill Us.[21][22] In September, he ran a full marathon in the Namib Desert without water, under the supervision of Dr. Thijs Eijsvogels.[23]

Wim Hof Method

Wim Hof markets a regimen, the Wim Hof Method (WHM), created alongside his son Enahm Hof. The method involves three "pillars": cold therapy, breathing and meditation.[24] It has similarities to Tibetan Tummo meditation and pranayama, both of which employ breathing techniques.[25]

Breathing

There are many variations of the breathing method. The basic version consists of three phases as follows:

- Controlled breathing: The first phase involves 30-40 cycles of breathing. Each cycle goes as follows: take a deep breath in, fully filling the lungs. Breathe out by passively releasing the breath, but not forcefully. Repeat this cycle at a steady pace thirty to forty times. Hof says that this form of hyperventilation may lead to tingling sensations or light-headedness.

- Exhalation: After completion of the 30-40 cycles of controlled hyperventilation, take another deep breath in, and let it out. Do not fully empty the lungs, instead let the air out until you would need to contract your diaphragm to expel more air, maintaining neutral air pressure between the lungs and environment, for anywhere between 1 to 3 minutes.

- Breath retention: When strong urges to breathe occur, take a full deep breath in. Hold the breath for around 15 – 20 seconds and let it go. The body may experience a normal head-rush sensation.

These three phases may be repeated for three or more consecutive rounds.[25]

Scientific investigations

Preliminary and proof-of-principle studies of Hof's method, as well as similar breathing practices, have shown that hyperventilating can temporarily suppress the innate immune response as well as temporarily increase heart rate and adrenaline levels. However, the broader medical claims made by Hof, such as the treatment of cancer and auto immune disease, have not been validated by any rigorous peer reviewed research.[26][27][28]

Resistance to cold

When exposed to cold, the human body can increase heat production by shivering, or non-shivering process known as thermogenesis in which BAT, also known as brown fat, converts chemical energy to heat. Mild cold exposure is known to increase BAT activity.[29] A group of scientists in the Netherlands wondered whether frequent exposure to extreme cold, as practiced in the Wim Hof Method, would have comparable effects. The Hof brothers are identical twins, but unlike Wim, Andre has a sedentary lifestyle without exposure to extreme cold. The scientists had them practice Wim's breathing exercises and then exposed them to the lowest temperature that would not induce shivering. They concluded that, "No significant differences were found between the two subjects, indicating that a lifestyle with frequent exposures to extreme cold does not seem to affect BAT activity and CIT."[30] Both had rises of 40% of their metabolic rates over the resting rate, compared to a maximum of 30% observed in young adults. However, their brown fat percentage – while high for their age – was not enough to account for all of the increase. The rest was due to their vigorous breathing, which increased the metabolic activity in their respiratory muscles. The researchers cautions that the "results must be interpreted with caution given the low subject number and the fact that both participants practised the g-Tummo like breathing technique."[29]

The related g-Tummo involves special breathing accompanied by meditation involving mental images of flames at certain locations in the body. There are two types of breathing, "forceful" and "gentle". A scientific study found that only the forceful type results in an increase in body temperature, and that meditation was required to sustain the temperature increase.[31]

Immune system suppression

Peter Pickkers and his PhD student Matthijs Kox of the Radboud University Medical Center in the Netherlands took blood samples from Hof before and after his regimen of breathing, meditation and an 80-minute full-body ice bath, and found that afterwards he had reduced levels of proteins associated with the immune response.[26]

Pickkers and Kox injected him with an endotoxin that normally would stimulate a rapid immune response. Most subjects responded with flu-like symptoms (fever, headaches and shivering), with affected cells releasing signalling proteins called cytokines. Hof, on the other hand, had no flu-like symptoms and half as many cytokines as control subjects. Moreover, later, after he had trained some volunteers for a week, they too had reduced symptoms.[26]

Pickkers and Kox attributed the effect on the immune system to a stress-like response. In the hypothalamus, stress messages from the brain trigger a release of adrenaline, which increases the pumping of blood and releases glucose, both of which can help the body deal with an emergency. It also suppresses the immune system. In Hof and the trained subjects, the adrenaline release was higher than it would be after a person's first bungee jump.[26][32] It is not yet known which part of the training (cold exposure, breathing or meditation) is primarily responsible for the effect, or whether there are long-term training effects.[29]

Controversies

People have died while attempting the Wim Hof Method.[33][34] Four practitioners of the WHM drowned in 2015 and 2016, and relatives suspected the breathing exercises were to blame.[33][34]

Critics of Hof say he overstates the benefits of his method, giving false hope to people suffering from serious diseases, and some of his claims have been uncritically reported by the media.[35] On his website he says that it has reduced symptoms of several diseases including rheumatoid arthritis, multiple sclerosis, and Parkinson's disease;[25] He has also said it might cure some forms of cancer.[35] Wouter van Marken Lichtenbelt, one of the scientists who studied Hof, stated that "[Hof's] scientific vocabulary is galimatias. With conviction, he mixes in a non-sensical way scientific terms as irrefutable evidence."[29] However, Van Marken Lichtenbelt goes on to say: "When practicing the Wim Hof Method with a good dose of common sense (for instance, not hyperventilating before submerging in water) and without excessive expectations: it doesn't hurt to try."[29]

Media appearances

Hof appears in the music video for "My Last Breath" by James Newman, the United Kingdom entry for the Eurovision Song Contest 2020.[36][37]

Hof appears in season one of the Netflix series Goop Lab.[38]

Publications

- Hof, Wim (1998). Klimmen in stilte [Climbing in silence] (in Dutch). Altamira. ISBN 9789069634395.

- Hof, Wim (2000). De top bereiken is je angst overwinnen [Reaching the top is overcoming your fear] (in Dutch). Andromeda. ISBN 9789055991136.

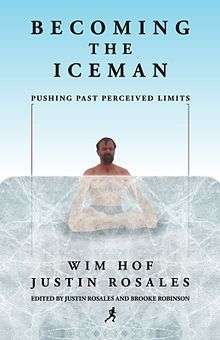

- Hof, Wim; Rosales, Justin (2012). Becoming the Iceman : pushing past perceived limits. Mill City Press. ISBN 9781937600464.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hof, Wim; Jong, Koen A.M. de (2015). Koud kunstje : wat kun je leren van de iceman?. Uitgeverij Water. ISBN 9789491729256.

See also

- Kundalini energy

References

- Shea, Daisy-May Hudson and Matt (16 July 2015). "ICEMAN". Vice. Retrieved 29 March 2019.

- Hedegaard, Erik (3 November 2017). "Wim Hof Says He Holds the Key to a Healthy Life – But Will Anyone Listen?". Rolling Stone. Retrieved 22 February 2019.

- Carney, Scott (2017). What doesn't kill us : how freezing water, extreme altitude, and environmental conditioning will renew our lost evolutionary strength. Potter/Ten Speed/Harmony/Rodale. ISBN 9781623366919.

- Carney, Scott (2011). "The Iceman Cometh". Scott Carney. Archived from the original on 27 June 2018. Retrieved 22 February 2019.

- Hof & Rosales 2012, p. 10

- Joe Rogan (interviewer) and Wim Hof (21 October 2015). Wim Hof (podcast). Joe Rogan Experience. 712. Joe Rogan. Retrieved 23 February 2019.

- Innerfire. "Innerfire - Wim Hof, The Iceman - Innerfire". Retrieved 18 July 2015.

- Tang, Vivienne. "Wim Hof: The Iceman on Breathwork, Ice Baths, and How to Reset and Control Your Immune System". Destination Deluxe. Retrieved 18 September 2019.

- Farthest swim under ice - Guinness World Records. Guinnes World Records. 20 August 2012. Retrieved 22 February 2019.

- Science Explains How the Iceman Resists Extreme Cold. Smithsonian Mag. January 2020. Retrieved 10 February 2020.

- "Longest swim under ice - breath held (no fins, no diving suit)". Guinness World Records. Retrieved 22 February 2019.

- "Fastest half marathon barefoot on ice/snow". Guinness World Records. Retrieved 22 February 2019.

- Glenday, Craig (2015). Guinness world records 2015. Bantam Trade. p. 246. ISBN 9781101883808.

- "Full body ice contact endurance". Guinness World Records. 8 May 2011. Retrieved 22 February 2019.

- Sunday, Alex (29 December 2010). "Dutchman Aims to Take Longest Ice Bath". CBS News. Retrieved 22 February 2019.

- "Longest duration full body contact with ice". Guinness World Records. Retrieved 22 February 2019.

- "Longest duration full body contact with ice". World Open Water Swimming Association. Retrieved 29 September 2019.

- "Dutch Iceman to climb Everest in shorts: It's all about the inner fire". ExplorersWeb. 1 March 2007. Retrieved 26 February 2019.

- Kathmandu (29 May 2007). "Everest climber falls short". The Age. Retrieved 26 February 2019.

- Iceman Wim Hof on Kilimanjaro Summit. YouTube. 14 February 2009. Retrieved 18 July 2015.

- Kilimanjaro Expedition 2016 With Iceman Wim Hof, retrieved 13 May 2020

- "What Doesn't Kill Us by Scott Carney: 9781635652413 | PenguinRandomHouse.com: Books". PenguinRandomhouse.com. Retrieved 13 May 2020.

- Innerfire. "Wim Hof Blog". Retrieved 18 July 2015.

- Hof, Wim. "Wim Hof Method". wimhofmethod.com. Retrieved 23 February 2019.

- Wim Hof, Wim. "The Benefits of Breathing Exercises". Wim Hof Method. Retrieved 23 February 2019.

- Houtman, Anne; Scudellari, Megan; Malone, Cindy; Singh-Cundy, Anu (2015). "22. Endocrine and immune systems" (PDF). Biology Now. W. W. Norton & Company. pp. 388–405. ISBN 978-0393906257. Retrieved 23 February 2019.

- Muzik, Otto; Reilly, Kaice T.; Diwadkar, Vaibhav A. (15 May 2018). "'Brain over body'–A study on the willful regulation of autonomic function during cold exposure". NeuroImage. 172: 632–641. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2018.01.067. ISSN 1053-8119. PMID 29438845.

- Buijze, G. A.; Jong, H. M. Y. De; Kox, M.; Sande, M. G. van de; Schaardenburg, D. Van; Vugt, R. M. Van; Popa, C. D.; Pickkers, P.; Baeten, D. L. P. (2 December 2019). "An add-on training program involving breathing exercises, cold exposure, and meditation attenuates inflammation and disease activity in axial spondyloarthritis – A proof of concept trial". PLOS One. 14 (12): e0225749. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0225749. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 6886760. PMID 31790484.

- van Marken Lichtenbelt, Wouter (11 July 2017). "Who is the Iceman?". Temperature. 4 (3): 202–205. doi:10.1080/23328940.2017.1329001. PMC 5605164. PMID 28944263.

- Vosselman, Maarten J.; Vijgen, Guy H. E. J.; Kingma, Boris R. M.; Brans, Boudewijn; van Marken Lichtenbelt, Wouter D.; Romanovsky, Andrej A. (11 July 2014). "Frequent Extreme Cold Exposure and Brown Fat and Cold-Induced Thermogenesis: A Study in a Monozygotic Twin". PLOS One. 9 (7): e101653. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0101653. PMC 4094425. PMID 25014028.

- Kozhevnikov, Maria; Elliott, James; Shephard, Jennifer; Gramann, Klaus; Romanovsky, Andrej A. (29 March 2013). "Neurocognitive and Somatic Components of Temperature Increases during g-Tummo Meditation: Legend and Reality". PLOS One. 8 (3): e58244. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0058244. PMC 3612090. PMID 23555572.

- Kox M, van Eijk LT, Zwaag J, van den Wildenberg J, GJ Sweep FC, van der Hoeven JG, Pickkers P (20 May 2014). "Voluntary activation of the sympathetic nervous system and attenuation of the innate immune response in humans". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 111 (20): 7379–7384. doi:10.1073/pnas.1322174111. PMC 4034215. PMID 24799686. Retrieved 28 January 2017.

- Tijmstra, Fannie; Bomers, Loes (10 June 2016). "'Iceman' onder vuur" ['Iceman' under fire] (in Dutch). EenVandaag. Retrieved 23 February 2019.

- Duin, Roelf Jan (2 July 2016). "'Iceman'-oefening eist opnieuw leven" ['Iceman' exercise claims a new life]. Het Parool (in Dutch). Retrieved 23 February 2019.

- van Erp, Pepijn (1 January 2016). "Wim Hof's Cold Trickery". Pepijn van Erp. Retrieved 22 February 2019.

- James Newman - My Last Breath - United Kingdom 🇬🇧 - Eurovision 2020 on YouTube

- Reilly, Nick (27 February 2020). "James Newman to represent the UK at Eurovision 2020". Retrieved 3 March 2020.

- "The Goop Lab Netflix On The Wim Hof Method & Cold Therapy". Goop. Retrieved 13 May 2020.

Further reading

- Buijze, Geert A.; Hopman, Maria T. (December 2014). "Controlled Hyperventilation After Training May Accelerate Altitude Acclimatization". Wilderness & Environmental Medicine. 25 (4): 484–486. doi:10.1016/j.wem.2014.04.009. PMID 25443751.

- Erp, Pepijn van (25 January 2015). "'Iceman' Wim Hof over the top". Pepijn van Erp. Retrieved 24 February 2019.

- Fehily, Toby (7 October 2017). "What Doesn't Kill Us, To Be a Machine: books on extreme measures". Retrieved 3 November 2017.

- Ferenstein, Gregory (30 September 2018). "How To Learn The Wim Hof Method, Even If You're Crazy Busy". Forbes. Retrieved 23 February 2019.

- Fuentes, Tamara (6 March 2018). "Science Reveals Why This Man Can Withstand Insanely Cold Temperatures for Hours". Men's Health. Retrieved 23 February 2019.

- Hudson, Daisy-May; Shea, Matt (15 July 2015). "ICEMAN". Vice. Retrieved 22 February 2019.

- Kox, Matthijs; Stoffels, Monique; Smeekens, Sanne P.; van Alfen, Nens; Gomes, Marc; Eijsvogels, Thijs M.H.; Hopman, Maria T.E.; van der Hoeven, Johannes G.; Netea, Mihai G.; Pickkers, Peter (June 2012). "The Influence of Concentration/Meditation on Autonomic Nervous System Activity and the Innate Immune Response". Psychosomatic Medicine. 74 (5): 489–494. doi:10.1097/PSY.0b013e3182583c6d. PMID 22685240.

- Learn, Joshua Rapp. "Science Explains How the Iceman Resists Extreme Cold". Smithsonian (22 May 2018). Retrieved 23 February 2019.

- van Middendorp, Henriët; Kox, Matthijs; Pickkers, Peter; Evers, Andrea W. M. (21 July 2015). "The role of outcome expectancies for a training program consisting of meditation, breathing exercises, and cold exposure on the response to endotoxin administration: a proof-of-principle study". Clinical Rheumatology. 35 (4): 1081–1085. doi:10.1007/s10067-015-3009-8. PMC 4819555. PMID 26194270.

- Muzik, Otto; Reilly, Kaice T.; Diwadkar, Vaibhav A. (May 2018). ""Brain over body"–A study on the willful regulation of autonomic function during cold exposure". NeuroImage. 172: 632–641. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2018.01.067. PMID 29438845.

- Joe Rogan (interviewer) and Wim Hof (24 October 2016). Wim Hof (podcast). Joe Rogan Experience. 865. Joe Rogan. Retrieved 23 February 2019.

- Weston, Gabriel (23 February 2017). Ice Man (clip) (Television). Incredible Medicine: Dr Weston's Casebook, Series 1. 2. BBC. Retrieved 23 February 2019.