William Morrison (chemist)

William Morrison (23 August 1855 – 29 August 1927) was a Scottish chemist. His background in chemistry piqued his interest in improving storage batteries. He concentrated on how to produce the most available energy for a unit of weight for efficiency in the working of an individual battery cell. Eventually, he developed storage batteries far more powerful than what had then been available. To demonstrate his batteries, Morrison installed 24 of them on a common horse-drawn carriage and attached an electric motor to the rear axle to be powered by them. Through various innovations, he developed the controls for the power used and the vehicle's steering so that the driver had complete control. Morrison invented the first practical self-powered four-wheeled electric carriage in the United States. His electric vehicle was the first to be driven in Chicago and in his hometown of Des Moines, Iowa. This electric horseless buggy of the late 19th century helped pave the way for the hybrid electric automobile of the 21st century.

William Morrison | |

|---|---|

1896 | |

| Born | 23 August 1855 Scotland, UK |

| Died | 29 August 1927 (aged 72) California, US |

| Nationality | Scottish |

| Occupation | Chemist |

| Children | 3 |

Early life and education

Morrison was born in Scotland in 1855.[1] He attended local schools for his initial education; his interests as a young boy were chemistry, electricity and making storage batteries.[2]

He attended a Scottish university where he studied chemistry.[3] Morrison emigrated from Scotland to America in 1880 and settled in Des Moines, Iowa.[4] He worked for jeweler Schmidt and Company as a watchmaker and worked under jewelers Marguart and Lumbard.[5][6] He lived at an upscale residence—the Victoria Hotel.[1]

Electric carriages

Morrison had a secret basement laboratory in downtown Des Moines where he worked on storage batteries and a self-propelled electric carriage. He referred to it as "the Cave".[1] He constructed a prototype of the first electric carriage in 1887.[7] Morrison had a mechanical engineer, Dr. Lew Arntz, working with him who assembled what he designed.[8] Between 1888 and 1890 Morrison designed a second version of his electric carriage which had improvements in its electric motor, gear train, batteries and steering mechanism.[9] The modifications made his carriage practical and useful and is the one that became famous—the first practical electric automobile built in the United States.[10][11] To demonstrate the usefulness of Morrison's invention, the vehicle was entered into the 1890 Seni Om Sed parade in Des Moines where there were 85,000 to 100,000 spectators.[7][12] The battery-powered vehicle was carrying seven passengers.[13] The chemist drove his electric automobile all over the city for weeks after the parade. It was in several notable races.[14] The spectacle of the first practical automobile being on the streets of Des Moines was written up in multiple newspapers and journals. Word spread worldwide of the carriage that required no horses and was mobile under its own power.[1] Before the end of the year Morrison had received over 16,000 letters requesting information on his self-powered electric carriage (auto-mobile).[7]

Morrison claimed that his horseless carriage was the first successful practical passenger automobile of any kind in the world and offered $5,000 (in 1890 dollars ) to anyone that could show photographs otherwise.[15] Trade publications Western Electrician of Chicago and Scientific American of New York backed up his claims.[15] The award was never collected.[16][17]

Description

Morrison's electric carriage could carry up to twelve passengers on its the three bench seats. The vehicle could move at a walking pace or cruise at 14 miles per hour (23 km/h) on a flat and even road. It had a maximum speed of 20 miles per hour (32 km/h). It was steered by a small horizontal wheel controlled by the driver's hands. The steering wheel had a vertical rod apparatus attached to a rack and pinion gear structure that responded to the smallest turn and altered the angle of the front wheels to change the vehicle's course.[18][19] The carriage body was built by the Shaver Carriage Company in Des Moines as a normal surrey, but without the features necessary to attach horses. The four wooden wheels were steel-rimmed for extra protection against rough roads.[7] The self-propelled mobile carriage had a friction clutch that transferred the electric motor power to the rear wheels by way of gears.[16]

Morrison produced twelve electric horseless carriages, including the original 1897 prototype. [20] The eleven carriages Morrison designed and had built after the prototype sold for $3,600 each.[7] None of them exist today.[21] His concept of electric automobiles became popular, and before the end of the 19th century about a third of all cars were electric.[22] The popularity of the electric horseless carriages peaked in 1912 when over 30,000 in the United States were registered as being run only by electric batteries. They were known as an electric car (short for electric carriage).[22] The shift to gas-powered vehicles then dominated the latter half of the 20th century. The first hybrid vehicle using a combination of a gasoline engine and an electric motor, was released in 1997; this concept became popular in the 21st century.[23]

Batteries

The 24 storage battery cells that produced an output of 112 amps at 58 volts were stored under the first row of seats where the driver sat.[16] They weighed 768 pounds (348 kg) and ran a four horsepower modified trolley electric motor attached to the rear wheels to propel the carriage.[24] The electromagnetic coil was rewound by Morrison to be practical for his batteries that ran at about 15% of a trolley car's voltage.[25] The vehicle's speed was dependent on how many cells were in use at any one time.[26] It had three speeds which were dependent upon grouping together with switches battery cells in quantities of 8, 12 or 24.[27] The driver controlled the speed and steering.[28] The batteries had to be recharged after every 50 miles (80 km) of driving. That was as far as a vehicle could travel in a day as the batteries by then ran out of power. They were then recharged, which was done at night and took twelve hours.[1]

American Battery Company

Harold Sturgis and John B. MacDonald of the American Battery Company in Chicago each bought one of Morrison's electric vehicles at a cost of $3,600.[14][29][30] They were the third and fourth vehicles Morrison made and were constructed at the Shaver Carriage Company's facilities in east Des Moines.[15] Sturgis had Morrison construct his electrical carriage 1890 and 1891.[31] It was finished on 9 November 1891.[15] The new vehicle was shipped by rail to him in Chicago on 5 December 1891.[32][33] It took a few days to arrive.[34][35] The sale of this electric carriage to Sturgis is the first documented sale of an electric car in America.[18][36]

MacDonald's vehicle began construction by Morrison in mid-1891.[37][38] Finished in mid-1892 and shipped to him from Des Moines in late July, it arrived in Chicago on Monday, 8 August 1892.[39] It came with a three-horse power electric motor that propelled it and a 24-cell set of storage batteries.[40] MacDonald installed new Morrison batteries on the following day in preparation for a trial run on 10 August. That day marked the historic event when an electric vehicle was driven in Chicago for the first time.[41] With four other people in the electrically propelled carriage, it went from MacDonald's barn on Monroe Street where it was stored to the company's office in downtown Chicago at Monroe Boulevard and LaSalle Street.[42] The travel time for the two-and-a-half mile trip was 22 minutes. It was stopped several times for crowds of people that had gathered to see the strange wagon with no horses.[43]

The Morrison–MacDonald carriage then was backed up to the front door of the company's office and wires connected to the batteries on board for recharging. After receiving a fresh charge, MacDonald invited three other men to ride back with him to his residence. They were George T. Burroughs, vice president of the American Battery Company, Lucius Otis Jenkins, and a Western Electrician journalist. At 4:00 o'clock in the afternoon MacDonald drove the carriage from the company office building east on West Quincy Street to Clinton Street then to Jackson Street and then west to Jackson Boulevard to his residence on the corner of Monroe Street and Winchester Avenue.[39]

MacDonald used his Morrison Electric vehicle to promote his company's batteries. Beginning in September of 1892 he drive his friends and reporters around the city in the vehicle.[44] When it was driven in downtown Chicago the crowds that gathered to see it were so great that the police had to direct them away to clear a path for it to even move.[38] Sturgis exhibited his Morrison Electric vehicle at the 1893 Chicago World's Fair.[45] It won all the awards in the electric carriage category for American models, since it was the only American vehicle of the six electric vehicles entered.[18] Displayed at the fair's Electricity Building, thousands of people rode in the Morrison Electric car when it was driven in an enclosed area by Edgar Rice Burroughs. After the fair came to an end the vehicle was taken around the country to promote the sale of Morrison Electric vehicles and the American Battery Company's products.[46]

In early 1895, Sturgis attempted to construct his own electric vehicle for the forthcoming Chicago Times-Herald automobile race.[47] After failing, he simply modified the Morrison Electric car he already had.[48] He removed the overhead canopy. The steel rims on the wooden wheels were replaced with hard rubber rims. He then removed the old electric motor and replaced it with a stronger one. The most significant modification was the removal of the third bench seat. This allowed Sturgis to add more batteries to extend the vehicle's range before they needed recharging.[18] Sturgis and Morrison entered the vehicle in the race. Six inches (150 mm) of snow fell on race day. Sturgis' vehicle only managed to travel 13 miles (21 km) of the course's 53 miles (85 km) until the batteries ran out of power. His team was awarded a $500 prize for their attempt.[47][49]

Mechanical innovations

Morrison assembled additional electric carriages and demonstrated them on the streets of Des Moines in 1892 to show how practical and useful his mechanism was. The twelve-passenger vehicle was advertised as capable of being used on city streets as well as country roads. News reports talked of the innovative new electric motor he had designed that the driver's foot on a pedal controlled.[16] Reports also described the unique steering apparatus controlled by a small hand wheel that the driver controlled,[24] and that it took only one person to operate the electric self-propelled carriage.[50][51]

Sturgis entered his Morrison Electric car in the Minneapolis Cycle Show on 6 April 1896. The vehicle had solid rubber tires at that time instead of steel-rimmed wooden wheels. These tires were made by the Hartford Rubber Works Company. Sturgis gave rides to attendees who queued up in long lines at the show. He drove his Morrison Electric around the streets of Minneapolis for days after the show so others could see the electric automobile.[21]

Undercarriage mechanisms

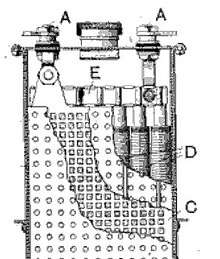

Figure 1 – Power conversion apparatus to regulate power going to the rear wheels.[52]

Figure 1 – Power conversion apparatus to regulate power going to the rear wheels.[52] Figure 2 – Close up of the rear axle showing the gear train on the right side that operated the wheels.[39]

Figure 2 – Close up of the rear axle showing the gear train on the right side that operated the wheels.[39]

Figure 4 – Front wheels and axle showing a type of rack and pinion steering.[54]

Figure 4 – Front wheels and axle showing a type of rack and pinion steering.[54] Figure 5 – Front view under the seats showing the batteries used to power the vehicle's movement.[24]

Figure 5 – Front view under the seats showing the batteries used to power the vehicle's movement.[24]

Battery development

William Morrison's principle interest was the development of efficient storage batteries.[5] He patented his innovations and became wealthy when he sold the rights to his battery invention to various battery companies and collected royalties.[55] Morrison had over 88 patents related to batteries.[56] He developed the electrically propelled horseless carriage, later known as the electric automobile, only to prove the importance and value of his batteries–not to invent a self-propelled electric vehicle. He wanted to show how powerful his batteries were and propelling a horseless carriage of 3,000 pounds demonstrated this.[57] The American Battery Company bought several of Morrison's battery patent rights in 1891.[58] He received royalties for his batteries produced by the company and for copies of his electric car that were made.[14][47][59] They moved their branch of the Morrison Electric Company that made the electric cars to Kansas City, Missouri in 1910 and for years made copies of the electric carriages there.[55]

In 1890, Morrison devised a new type of storage battery with glass-wool insulation on the electrode plates.[60] The Morrison Storage Battery allowed the normal internal operation of the battery to function correctly. It prevented the shedding of material from the positive plates that caused short-circuiting. The old-style batteries at that time had that problem which caused inefficiency.[61] Morrison's batteries were much more efficient because his ideas reduced the weight of the battery and increased its power output.[62][63]

Morrison obtained a patent in 1891 for his invention of improved storage batteries that led to the first practical electric car in America.[11] That increased battery efficiency made it possible for 24 of his batteries to produce enough power to run a horseless carriage with a group of people aboard the vehicle.[64] Patent No. 464,676 says in part:

Secondary Batteries. Wm Morrison of Des Moines is Assignor to the Hess Electric Company. Application filed Oct 27, 1890. An electrode for secondary batteries consisting of a stratum body portion of active material or material to become active a layer coating or covering of fibrous glass wool disposed of the face or side of the body portion of active material and confining non conducting plates.[65][66]

The Universal Electric Storage Battery Company of Chicago came into existence in 1905.[67] It made the Morrison battery for industrial applications in lighting, electric cars, railroads and power plants.[68] One use of these batteries was for a hybrid vehicle being manufactured by Chicago & Alton company.[69] Another was as an ignition battery to start cars.[70]

Personal and later life

Morrison was a tall, husky, well-groomed man with dark hair. A vegetarian who kept to himself, he often found himself out of place with the locals and was known as a bizarre electrical wizard—a self-centered eccentric who did peculiar experiments.[71]

In his thirties, Morrison married a 20-year-old Mary Reily on 16 July 1892.[72] They had one child, William Earl, who died as a toddler.[3] Mary died at approximately the same time. While living in Chicago, Morrison was shown a photograph by Mrs. A. H. O'Neill of Mary's 20-year-old sister, Elsie Myer of Grand Forks, North Dakota. After they met, Morrison married her two months later.[73] They had a son who died at 16 months and later a daughter who outlived Morrison. Elsie died on 5 September 1950.[55]

Morrison became involved in the gold-mining business in California during his later years.[74] He died in Northern California in 1927, and his body was returned to Des Moines for burial at Woodland Cemetery.[1]

References

Citations

- "William Morrison / Inventor 1850-1927". The Des Moines Register. Des Moines, Iowa. 2 February 2003. p. 17 – via Newspapers.com

- McClellan 1963, p. 561–562.

- McClellan 1963, p. 561.

- Rosenberg 2008, p. 173.

- McClellan 1963, p. 563.

- "His Genius Rewarded". Parsons Daily Eclipse. Parsons, Kansas. 11 July 1993. p. 4 – via Newspapers.com

- Carroll 2014, p. 234.

- "Des Moines Men Made One of the First Automobiles". The Des Moines Register. Des Moines, Iowa. 5 January 1919. p. 24. Archived from the original on 6 February 2020. Retrieved 6 February 2020 – via Newspapers.com

- Harter 2015, p. 8.

- World 1891, p. 453.

- Shukla 2016, p. 199.

- "The Elbert Files: Bring back Seni Om Sed". Business Record. 2020. Retrieved 4 March 2020.

- "Book tells Iowas story in early auto history". The Des Moines Register. Muscatine, Iowa. 1 December 2007. p. 38 – via Newspapers.com

William Morrison, who earned a place in automotive history on Sept. 4, 1890, when he drove his electric-powered carriage in Des Moines' annual Seni Om Sed parade.

- Larson 2008, p. 212.

- "The Electric Auto Was Born In Des Moines". The Des Moines Register. Des Moines, Iowa. 9 June 1907. p. 8 – via Newspapers.com

- Beitz 1963, p. 12.

- "Anniversary". The Des Moines Register. Des Moines, Iowa. 30 August 2007. p. 31 – via Newspapers.com

- Anderson 2005, p. 18.

- Simen 1996, p. 90.

- Lucendo 2019, p. 19.

- Larson 2008, p. 214.

- Pistoia 2001, p. 295.

- Pinto 2019, p. 29.

- "An electric Carriage". The Muscaline Journal. Muscaline, Iowa. 5 February 1892. p. 4. Archived from the original on 4 February 2020. Retrieved 4 February 2020 – via Newspapers.com

- "Electric Vehicles History Part III". Electric Vehicles News. 2020. Retrieved 21 February 2020.

- "An Electric Carriage". The Davenport Democrat. Davenport, Iowa. 28 January 1892. p. 1. Archived from the original on 30 January 2020. Retrieved 4 February 2020 – via Newspapers.com

- Electrician 1893, p. 205.

- "Light of Science". The Times. Streator, Illinois. 1 August 1892. p. 4 – via Newspapers.com

- Lucendo 2019.

- "Ed and His Electric Flyer". Edgar Rice Burroughs, Inc. 2020. Archived from the original on 14 June 2019. Retrieved 4 February 2020.

- "American Automobiles / The Morrison Electric Automobile & The William Morrison Co". Farber and Associates. 2012. Archived from the original on 12 October 2019. Retrieved 4 February 2020.

- "An Electrical Carriage". The Des Moines Register. Des Moines, Iowa. 5 December 1891. p. 7. Archived from the original on 30 January 2020. Retrieved 4 February 2020 – via Newspapers.com

- "City News". Muscaline News. Muscaline, Iowa. 11 December 1891. p. 1 – via Newspapers.com

- Popular 1892, p. 252.

- Segrave 2019, p. 9.

- Warner 2015, p. 15.

- Doolittle 1916, p. 24.

- "First Car Seen 23 Years Ago / Was Built by William Morrison Des Moines, in 1891 - Industry Firmly Established". The Rock Island Argus. Rock Island, Illinois. 30 November 1915. p. 10 – via Newspapers.com

- Electrician 1892, p. 145.

- "An Electric Wagon". Altoona Tribune. Altoona, Pennsylvania. 12 August 1892. p. 3 – via Newspapers.com

- "An Electric Wagon". Pittsburgh Daily Post. Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. 11 August 1892. p. 5 – via Newspapers.com

- "A Wagon Propelled by Lightning". The Memphis Appeal-Avalanche. Memphis, Tennessee. 11 August 1892. p. 8 – via Newspapers.com

- "A Wagon Run by Electricity". The Baltimore Sun. Baltimore, Maryland. 11 August 1892. p. 6 – via Newspapers.com

- Barber 2011, p. 71.

- "Saturn wouldn't be the first Iowa=built car". The Gazette. Cedar Rapids, Iowa. 23 February 1985. p. 5 – via Newspapers.com

- "The Electric Auto was "Born" in Des Moines". The Register and Leader. Des Moines, Iowa. 9 June 1907. p. 1. Archived from the original on 24 January 2020. Retrieved 4 February 2020 – via Newspapers.com

The first automobile in the world was invented by a Des Moines man, manufactured in Des Moines and run on Des Moines streets. All of these facts will be found set forth in the leading trade journals of 1891, especially the 'Western Electrician' and the 'Scientific American', so that Mr. Morrison's rights to be hailed as the inventor of the automobile are established beyond all question.

- McClellan 1963, p. 566.

- Burton 2013, p. 19.

- Anderson 2005, p. 19.

- "An Electric Carriage". Quad-City Times. Davenport, Iowa. 28 January 1992. p. 5 – via Newspapers.com

- "Iowa Happenings". Muscaline Semi-Weekly News Tribune. Muscaline, Iowa. 27 January 1892. p. 5 – via Newspapers.com

- Western Electrician V22 1892, p. 277.

- Electrician 1891, p. 333.

- Electrician 1892, p. 146.

- McClellan 1963, p. 568.

- "The Front Row". Des Moines Tribune. Des Moines, Iowa. 5 September 1979. p. 3. Archived from the original on 30 January 2020. Retrieved 4 February 2020 – via Newspapers.com

- "D.M.'s Eldridge beat Henry Ford". The Des Moines Register. Des Moines, Iowa. 5 June 1996. p. 76 – via Newspapers.com

- "An Electric Wagon". The Pittsburgh Post. Pittsburg, Pennsylvania. 11 August 1892. p. 5 – via Newspapers.com

- Mroz 2009, p. 197.

- Worthington 1910, p. 1259.

- Munn 1906, p. 40.

- "An electrifying Iowan: William Morrison, pioneer of battery technology and automobiles". Iowa Publishing Corporation. 2020. Archived from the original on 27 January 2020. Retrieved 4 February 2020.

By extension, Morrison's battery experiments led the inventor to create the first successful American electric car in 1890.

- "City Briefs / Invents battery". Des Moines Tribune. Des Moines, Iowa. 12 September 1910. p. 10 – via Newspapers.com

- "The First Charge of the Electric Car". Motley Fool. 2020. Archived from the original on 27 January 2020. Retrieved 4 February 2020.

- McGraw-Hill 1891, p. 460.

- "Patently American / Patent of the Day: December 8, 1891, US Patent No. 464, 676 – Electrode for Secondary Batteries, to William Morrison, of Des Moines, IA". Inventing America and US Patent Office. 2020. Archived from the original on 27 January 2020. Retrieved 4 February 2020.

- McGraw-Hill 1905, p. 855.

- "Answers to Inquirers / 10776". Wall Street Journal. New York City. 25 June 1906. p. 2 – via Newspapers.com

- "Gasoline Motor Car". The Lincoln State Journal. Lincoln, Nebraska. 19 October 1905. p. 10 – via Newspapers.com

- "Universal Firm going 25 Years". The Star Press. Muncie, Indiana. 17 June 1927. p. 24 – via Newspapers.com

- McClellan 1963, p. 562.

- "Record of the Week". The Saint Paul Globe. Saint Paul, Minnesota. 17 July 1892. p. 15 – via Newspapers.com

- "He Saw the Picture and Loved the Girl". The Iola Daily Record. Iola, Kansas. 15 November 1900. p. 4 – via Newspapers.com

- "Invention Here of First Electric Auto Amazed World in 1888 / Buried Here". The Des Moines Register. Des Moines, Iowa. 20 July 1947. p. 21 – via Newspapers.com

Bibliography

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Morrison Electric vehicles. |

- Anderson, Curtis (2005). Electric and Hybrid Cars:A History. McFarland & Company.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Barber, Herbert (2011). Story of the Automobile. Books on Demand.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Beitz, Ruth S. (1963). "Whirlwinds on Wheels". The Iowan. No. summer issue. Des Moines, Iowa: Heuss Printing.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Burton, Nigel (2013). History of Electric Cars. The Crowood Press Ltd.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Carroll, Andrew (2014). Discovering Am's Great Forgotten History. Crown Publishing Group.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Doolittle, James Rood (1916). Romance of Automobile Industry. J. R. Doolittle.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Electrician, Western (1891). "First Electric Carriage on the streets of Chicago". Western Electrician. 9 (12): 333.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Electrician, Western (1892). "First Electric Carriage on the streets of Chicago". Western Electrician. 11 (12): 145.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Electrician, Western (1893). "Electricity at the World'sFair". Western Electrician. 13 (17): 205.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Harter, Jim (2015). Early Automobiles:A History in Ad Line Art, 18900-1930. Wings Press.

America's first battery-powered carriage to successfully operate was built by Morrison of Iowa between 1888 and 1890.

CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Larson, Len (2008). Dreams to Automobiles. Xlibris Corporation.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lucendo, Jorge (2019). Cars of Legend. JL Publishing.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- McClellan, Keith (1963). The Morrison Electric: Iowa's First Automobile. The Annals of Iowa. 36. pp. 561–568.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- McGraw-Hill (1891). "Our Illustrated Record of Electrical Patents". Electrical World. 18.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- McGraw-Hill (1905). "The Morrison Storage Battery". Electrical World. 45.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Mroz, Albert (2009). Military Vehicles World War I. McFarland & Company. ISBN 0786439602.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Munn (1906). Scientific American, v94. Munn & Company.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Pinto, Lígia (2019). Third Annual Meeting of Portuguese Association. UMinho Editora.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Pistoia, G. (2001). Used Battery Collection and Recycling. Elsevier.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Popular, Electrical (1892). "A New Electric Carriage". Electricity; Popular Electrical Journal. 1 (20): 252.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Rosenberg, Chaim (2008). America at the Fair:Chicago's 1893 World's Columbian Exposition. Arcadia Publishing.

William Morrison's battery-powered surry, with its simple steering and braking mechanisms was America's first electric automobile.

CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Segrave, Kerry (2019). The Electric Car in America 1890-1922. McFarland & Company.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Shukla, Amritanshu (2016). Energy Security and Sustainability. CRC Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Simen, Patrick (1996). From Horses to Horsepower - The First 50 Years 1896 - 1946. McVey Marketing.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Warner, John (2015). The Handbook of Lithium-Ion Battery Pack Design. Elsevier Press. ISBN 9780128014561.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Western Electrician V22 (1892). "Morrison's Apparatus for Power Conversion". Western Electrician. 22 (20): 277.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- World, Electrical (1891). "A New Electrical Carriage". Electrical World. 18: 453–454.

This carriage has been in practical operation in the streets of Des Moines for some time and will soon be seen in Chicago.

CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Worthington, George (1910). Electrical Review, V57. McGraw Hill Publishing Co.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)