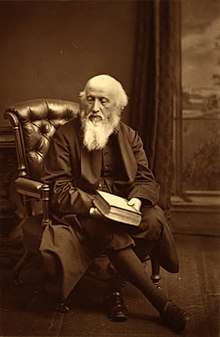

William Barnes

William Barnes (22 February 1801 – 7 October 1886) was an English writer, poet, Church of England priest, and philologist. He wrote over 800 poems, some in Dorset dialect, and much other work, including a comprehensive English grammar quoting from more than 70 different languages.

William Barnes | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 22 February 1801 Bagber, Dorset |

| Died | 7 October 1886 (aged 85) |

| Nationality | English |

| Occupation | priest, poet and philologist |

Life

Barnes was born at Rushay in the parish of Bagber, Dorset, the son of a farmer. His formal education finished when he was 13 years old.[1] Between 1818 and 1823 he worked in Dorchester, the county town, as a solicitor's clerk, then moved to Mere in neighbouring Wiltshire and opened a school.[1] While he was there he began writing poetry in the Dorset dialect, as well as studying several languages (Italian, Persian, German and French, in addition to Greek and Latin), playing musical instruments (violin, piano and flute) and practising wood-engraving.[1] He married Julia Miles, the daughter of an exciseman from Dorchester, in 1827. In 1835 he moved back to the county town, where again he ran a school[1] at first located in Durngate Street but which subsequently moved to South Street. By a further move, within South Street, the school became a neighbour of an architect's practice in which Thomas Hardy was an apprentice. The architect, John Hicks, was interested in literature and the classics, and when disputes about grammar occurred in the practice, Hardy used to visit Barnes next door for an authoritative opinion.[1] His other literary friends included Lord Tennyson and Gerard Manley Hopkins.

Barnes was ordained into the Church of England in 1847, taking a BD degree from St John's College, Cambridge, in 1851.[2] He served curacies at Whitcombe Church in Whitcombe, Dorset, 1847–52, and again from 1862. He became rector of St Peter's Church, Winterborne Came with Winterborne Farringdon, Dorset, from 1862 to his death. Shortly before his death he was visited at Came Rectory by Thomas Hardy and Edmund Gosse; in a letter, Gosse wrote that Barnes was "dying as picturesquely as he lived":

We found him in bed in his study, his face turned to the window, where the light came streaming in through flowering plants, his brown books on all sides of him save one, the wall behind him being hung with old green tapestry. He had a scarlet bedgown on, a kind of soft biretta of dark red wool on his head, from which his long white hair escaped on to the pillow; his grey beard, grown very long, upon his breast; his complexion, which you recollect as richly bronzed, has become blanched by keeping indoors, and is now waxily white where it is not waxily pink; the blue eyes, half shut, restless under languid lids.

— in The Life of William Barnes (1887) by Leader Scott, p325, quoted in Highways & Byways in Dorset (Macmillan & Co. Ltd, 1906) by Sir Frederick Treves, pp364-5

Barnes first contributed the Dorset dialect poems for which he is best known to periodicals, including Macmillan's Magazine; a collection in book form Poems of Rural Life in the Dorset Dialect, was published in 1844. A second collection Hwomely Rhymes followed in 1858, and a third collection in 1863; a combined edition appeared in 1879. A "translation", Poems of Rural Life in Common English had already appeared in 1868.

His philological works include Philological Grammar (1854), Se Gefylsta, an Anglo-Saxon Delectus (1849). Tiw, or a View of Roots (1862), and a Glossary of Dorset Dialect (1863).

Among his other writings is a slim volume on "the Advantages of a More Common Adoption of The Mathematics as a Branch of Education, or Subject of Study", published in 1834.

Barnes is buried in Winterborne Came churchyard beneath a Celtic cross. The plinth of the cross has the inscription: 'In Memory of William Barnes, Died 7 October 1886. Aged 86 Years. For 24 Years Rector of this Parish. This Memorial was raised to his Memory by his Children and Grandchildren."[3] There is also a statue of him in Dorchester town centre, outside St Peter's Church in that town.

Ralph Vaughan Williams set to music four of Barnes' poems, 'My Orcha'd in Lindèn Lea', in the "Common English" version ("Linden Lea"), 'Blackmwore Maidens', in the "Common English" version ("Blackmwore by the Stour"), "The Winter's Willow", and "In the Spring".

Linguistic purism

Barnes had a strong interest in language; he was fluent in Greek, Latin and several modern European languages. He called for the purification of English by removal of Greek, Latin and foreign influences so that it might be better understood by those without a classical education. For example, the word "photograph" (from Greek light+writing) would become "sun-print" (from Saxon). Other terms include "wortlore" (botany), "welkinfire" (meteor) and "nipperlings" (forceps).

This 'Pure English' resembles the 'blue-eyed English' later adopted by the composer Percy Grainger, and sometimes the updates of known Old English words given by David Cowley in How We'd Talk if the English had WON in 1066.

Style

As well as avoiding the use of these foreign words in his poetry, Barnes would often use a repetition of consonantal sounds similar to the Welsh poetry, cynghanedd. Examples of this can be heard in the lines, "Do lean down low in Linden Lea" and "In our abode in Arby Wood".

Example of Dorset dialect poetry

- THE LOVE CHILD

- Where the bridge out at Woodley did stride,

- Wi' his wide arches' cool sheäded bow,

- Up above the clear brook that did slide

- By the poppies, befoam'd white as snow;

- As the gilcups did quiver among

- The white deäsies, a-spread in a sheet.

- There a quick-trippèn maïd come along,-

- Aye, a girl wi' her light-steppèn veet.

- -

- Aye, a girl wi' her light-steppèn veet.

- An' she cried "I do praÿ, is the road

- Out to Lincham on here, by the meäd?"

- An' "oh! ees," I meäde answer, an' show'd

- Her the way it would turn an' would leäd:

- "Goo along by the beech in the nook,

- Where the children do plaÿ in the cool,

- To the steppèn stwones over the brook,-

- Aye, the grey blocks o' rock at the pool."

- -

- Aye, the grey blocks o' rock at the pool."

- "Then you don't seem a-born an' a-bred,"

- I spoke up, "at a place here about;"

- And she answer'd wi' cheäks up so red

- As a pi'ny leäte a-come out,

- "No, I liv'd wi' my uncle that died

- Back in Eäpril, an' now I'm a-come

- Here to Ham, to my mother, to bide,-

- Aye, to her house to vind a new hwome."

- -

- Aye, to her house to vind a new hwome."

- I'm asheämed that I wanted know

- Any more of her childhood or life

- But then, why should so feäir a child grow

- Where no father did bide wi' his wife;

- Then wi' blushes of zunrisèn morn,

- She replied "that it midden be known,

- "Oh! they zent me awaÿ to be born, -*

- Aye, they hid me when some would be shown."

- -

- Aye, they hid me when some would be shown."

- Oh! it meäde me a'most teary-ey'd,

- An' I vound I a'most could ha' groan'd-

- What! so winnèn, an' still cast azide-

- What! so lovely, an' not to be own'd;

- Oh! a God-gift a-treated wi' scorn

- Oh! a child that a squier should own;

- An' to zend her awaÿ to be born!-

- Aye, to hide her where others be shown!

* Words once spoken to the writer

- William Barnes, Poems of Rural Life in the Dorset Dialect (June 1879), p.382

See also

| Wikisource has original works written by or about: William Barnes |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: William Barnes |

- British literature

- West Country dialects

- Linguistic purism in English

- Lucy Baxter (daughter who wrote "Life of William Barnes" under name "Leader Scott")

- T. L. Burton (author of several books on Barnes's poetry)

Notes

- Hyams, John (1970). Dorset. B T Batsford Ltd. pp. 151–52. ISBN 0-7134-0066-8.

- "Barnes, William (BNS838W)". A Cambridge Alumni Database. University of Cambridge.

- Historic England. "Barnes Monument 3 Metres South of Nave of Church of St Peter (1303898)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 19 October 2010.

References

- Andrew Phillips, The Rebirth of England and the English: The Vision of William Barnes ISBN 1-898281-17-3

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: William Barnes |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to William Barnes. |

- William Barnes' Grave

- . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911.

- William Barnes at University of Toronto Libraries

Links to public-domain editions of Barnes' works

- Works by William Barnes at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about William Barnes at Internet Archive

- Works by William Barnes at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Poems of Rural Life, in the Dorset dialect (complete) at eBooks@Adelaide

- Poems of Rural Life, in the Dorset dialect, First collection (Third edition, 1862), full text at Google

- Hwomely Rhymes: A Second Collection of Poems in the Dorset Dialect (1859), full text at Google

- Poems of Rural Life, in the Dorset Dialect, Third Collection (1862), full text at Google