Whitehawk Camp

Whitehawk Camp is the remains of a Neolithic causewayed enclosure, on Whitehawk Hill in Brighton and Hove, East Sussex, England. It was inhabited sometime around 2700 BCE and is thus one of the earliest signs of human habitation in Brighton and Hove. The scheduled ancient monument has been described as one of the first monuments in England to be identified as being of national importance, and one of the most important Neolithic sites in the country.[1]

_-_geograph.org.uk_-_52046.jpg) Remains of Whitehawk Camp, with the grandstand of Brighton Racecourse behind. | |

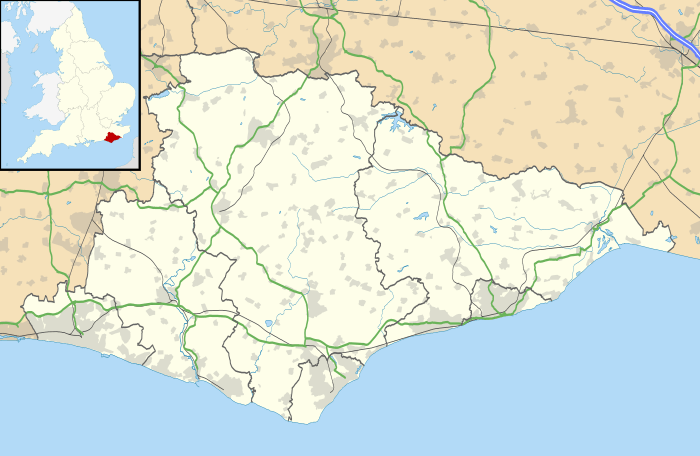

Shown within East Sussex | |

| Alternative name | Whitehawk causewayed enclosure |

|---|---|

| Location | Near Brighton, East Sussex |

| Coordinates | 50°49′39.94″N 0°6′41.76″W |

| Type | Causewayed enclosure |

| History | |

| Periods | Windmill Hill culture |

Background

Whitehawk Camp is a causewayed enclosure,[2] a form of earthwork which began to appear in England in the early Neolithic, from about 3700 BC.[3] Causewayed enclosures are areas that are fully or partially enclosed by segmented ditches (that is, ditches interrupted by gaps, or causeways, of unexcavated ground), often with earthworks and palisades in some combination.[4] The use to which these enclosures were put has long been a matter of debate, and many suggestions have been made by researchers.[5] They were previously known as "causewayed camps", since it was thought they were used as settlements: early investigators suggested that the inhabitants lived in the ditches, but this idea was later abandoned in favour of any settlement being within the enclosure boundaries.[5][6]

The causeways were difficult to explain in military terms, though it was suggested they could have been sally ports for defenders to emerge from and attack a besieging force;[7][8] evidence of attacks at some sites provided support for the idea that the enclosures were fortified settlements.[5][note 1] They may have been seasonal meeting places, used for trading cattle or other goods such as pottery, and if they were a focus for the local people, they may have been evidence of a local hierarchy with a tribal chief. There is also evidence that they played a role in funeral rites: material such as food, pottery, and human remains were deliberately deposited in the ditches.[9] They were constructed in a short time, which implies significant organization since substantial labour would have been required, for clearing the land, preparing trees for use as posts or palisades, and digging the ditches.[10]

In 1930, the archaeologist Cecil Curwen identified sixteen sites that were definitely or probably Neolithic causewayed enclosures.[11][12] Excavations at five of these had already confirmed them as Neolithic, and another four of Curwen's sites are now agreed to be Neolithic. [12] A few more were found over the succeeding decades,[13] and the list of known sites was significantly expanded with the use of aerial photography in the 1960s and early 1970s.[13][14]

The earlier sites were mostly found on chalk uplands, but many of the ones discovered from the air were on lower-lying ground.[13] Over seventy are known in the British Isles,[5] and they are one of the most common types of early Neolithic site in western Europe, with about a thousand known in all.[15] They began to appear at different times in different parts of Europe: the dates range from before 4000 BC in northern France, to shortly before 3000 BC in northern Germany, Denmark and Poland.[4] The enclosures in southern Britain and Ireland began to appear not long before 3700 BC, and continued to be built for at least 200 years. In a few cases enclosures that had already been built continued to be used as late as 3300 to 3200 BC.[16]

History

The camp reaches 396 feet (121 m) feet above sea level and measures 950 feet (290 m) feet by 700 feet (213 m) feet. It is made up of four concentric ditches broken up by causeways.[17] It is thought to have been used by people for between 155 and 230 years.[18]

The users of the camp grew cultivars of wheat and barley. Their tools were likely to have been made of wood, no flint sickles have been found on the hill. There are flint saws, which were used to cut through the bones of herded animals. There is not however much evidence of inhabitation. The location of the camp, between the two highest points of the hill, does not suggest it was built as something to be defended.[19]

The camp is one of only twelve remaining examples of a causewayed enclosure from the Windmill Hill culture in Britain and one of three known to have existed in the South Downs. It predates Avebury and Stonehenge by up to 1000 years.[20] The first written mention of the camp (as "White Hawke Hill") was in 1587.

From Whitehawk Hill other neolithic sites can be seen such as Chanctonbury Ring, Cissbury Ring and Hollingbury Hillfort.[21]

Excavations

The camp was the first scheduled ancient monument in Sussex.[20] It was excavated three times between 1929 and 1935. The 1932 excavation was carried out by Cecil Curwen and found the remains of humans buried together with fossilised sea urchins.[22] The 1935 dig was a rescue dig by students of Mortimer Wheeler, when a road was driven through the camp. Much of the camp was, by that time, destroyed by the construction of Brighton Racecourse and the allotments.[23]

The remains of four complete burials were found, including the bodies of an eight-year-old child and a young woman buried alongside the remains of a newborn child, as well as some other human bones. Also found in the infill of the circular ditches were many flint tools, potshards and animal bones.[24]

Only part of the causewayed enclosure has been investigated by archaeologists. When a small housing estate was built on the west side of the camp, a prehistoric ditch was excavated between 1991 and 1993.[25]

The Whitehawk Camp partnership was founded by the Centre for Applied Archaeology (University College London), Brighton & Hove City Council and Brighton and Hove Archaeological Society in 2014. It was given £99,300 by the Heritage Lottery Fund for a year long research project.[26] On 25 August 2014, the Whitehawk Dig took place. Archaeologist Owen O’Donnell said "This area is one of the most important in Britain and maybe even Europe in terms of the Neolithic times."[27] In addition to the dig, objects previously retrieved in the 1930s were photographed and repacked.[28]

Whitehawk woman

In 2018, the reconstructed face of the woman found in the 1930s excavations was shown at Brighton Museum & Art Gallery as part of a broader historical exhibition on the past inhabitants of Brighton. The 'Whitehawk Woman' was born in or near Wales and died in Brighton.[29] The woman had dark skin, was 1.45 metres tall (short even for a neolithic person), aged between 19 and 25. She was buried with a tiny skeleton of a baby, suggesting that she was either heavily pregnant or died whilst giving birth or very soon thereafter.[30][31]

In popular culture

- 'Whitehawk Hill' was a film installation made by Catlin Easterby, Simon Pascoe Anna Lucas and abandofbrothers. It was shown at Brighton Museum and Art Gallery from March 8 until April 10 2016.[32]

Notes

- For example, there is evidence that both Crickley Hill and Hambledon Hill were attacked.[5]

References

- Russell, Miles (2002), Prehistoric Sussex, Tempus, ISBN 0-7524-1964-1

- Oswald et al. (2001), pp. 156–157.

- Oswald et al. (2001), p. 3.

- Andersen (2019), p. 795.

- Whittle, Healy & Bayliss (2015), p. 5.

- Oswald et al. (2001), p. 9.

- Cunnington (1912), p.48.

- Curwen (1930), p. 50.

- Whittle, Healy & Bayliss (2015), pp. 10–11.

- Andersen (2019), p. 807.

- Curwen (1930).

- Oswald et al. (2001), p. 25.

- Oswald et al. (2001), p. 31.

- Mercer (1990), pp. 10–12.

- Andersen (2019), p. 796.

- Whittle, Healy & Bayliss (2015), pp. 1–2.

- "About Whitehawk Camp". Centre for Applied Archaeology. UCL. 25 July 2019. Archived from the original on 3 December 2019. Retrieved 3 December 2019.

- "Pastscape - Detailed Result: WHITEHAWK CAMP CAUSEWAYED ENCLOSURE". www.pastscape.org.uk. Archived from the original on 3 December 2019. Retrieved 3 December 2019.

- Bangs 2004, pp. 41-43.

- "Whitehawk Camp". www.brighton-hove.gov.uk. Brighton & Hove City Council. Archived from the original on 2 December 2019. Retrieved 2 December 2019.

- Bangs 2004, p. 13.

- Kenneth J. McNamara, The Star-Crossed Stone: The Secret Life, Myths, and History of a Fascinating Fossil, University of Chicago Press

- Seton-Williams 1988.

- "Brighton & Hove City Council". new.brighton-hove.gov.uk.

- "Image Details - 28537". Brighton Museums. Archived from the original on 3 December 2019. Retrieved 3 December 2019.

- "Whitehawk Camp Community Archaeology Project". Centre for Applied Archaeology. UCL. 25 July 2019. Retrieved 3 December 2019.

- Davies, Gareth (25 August 2014). "Digging up city's Neolithic past". The Argus. Retrieved 3 December 2019.

- Seymour 2018, p. 157.

- Romey, Kristin (24 January 2019). "These facial reconstructions reveal 40,000 years of English ancestry". National Geographic. Archived from the original on 3 December 2019. Retrieved 3 December 2019.

- Geggel, Laura (2019). "Photos: See the Ancient Faces of a Man-Bun Wearing Bloke and a Neanderthal Woman". livescience. Archived from the original on 3 December 2019. Retrieved 3 December 2019.

- Robertson, Dan (2020). "One of Brighton and Hove's earliest known residents – Whitehawk Woman". Discover. Retrieved 2020-06-11.

- Culture24 Reporter (9 February 2016). "A connection with prehistory: Artists create film about one of UK's first Neolithic ritual monuments | Culture24". Culture24. Archived from the original on 3 December 2019. Retrieved 3 December 2019.

Sources

- Andersen, Niels H. (2019) [2015]. "Causewayed Enclosures in Northern and Western Europe". In Fowler, Chris; Harding, Jan; Hofmann, Daniela (eds.). The Oxford Handbook of Neolithic Europe. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 795–812. ISBN 978-0-19-883249-2.

- Bangs, Dave (2004). Whitehawk Hill: Where the Turf Meets the Surf (1 ed.). Friends of Whitehawk Hill.

- Cunnington, M.E. (1912). "Knap Hill Camp". Wiltshire Archaeological and Natural History Magazine. 37: 42–65.

- Curwen, E.Cecil (April 1934). "Excavations in Whitehawk Neolithic Camp, Brighton, 1932-3". Antiquaries Journal. XIV (2): 99–133.

- Curwen, E.C. (1936). "Excavacations in Whitehawk Camp, Brighton, Third Season, 1935". Sussex Archaeological Collections. 77: 60–92.

- Drewett, P. (1994). "Dr V. Seton Williams' excavations at Combe Hill, 1962, and the role of Neolithic causewayed enclosures in Sussex". Sussex Archaeological Collections. 132: 7–24.

- Healy, Frances; Bayliss, Alex; Whittle, Alasdair (2015) [2011]. "Sussex". In Whittle, Alasdair; Healy, Frances; Bayliss, Alex (eds.). Gathering Time: Dating the Early Neolithic Enclosures of Southern Britain and Ireland. Oxford: Oxbow. pp. 207–262. ISBN 978-1-84217-425-8.

- Mercer, R.J. (1990). Causewayed Enclosures. Princes Risborough, UK: Shire Archaeology. ISBN 0-7478-0064-2.

- Orange, H.; Maxted, A.; Sygrave, J.; Richardson, D. (2015). "Whitehawk Camp Community Archaeology Project: A Report from the Archives". Archaeology International. 18: 51–55.

- Orange, H., Sygrave, J. and Maxted, A. (2015) An Evaluation Report to the Heritage Lottery Fund on the outcomes of the Whitehawk Camp Community Archaeology Project. ASE Project No: P106. Report No 2015202.

- Russel, M. (1991). An Archaeological Assessment at Whitehawk Neolithic Enclosure, Brighton, East Sussex (Report).

- Russell, M.; Rudling, D. (1996). "Excavations at Whitehawk Neolithic enclosure, Brighton, East Sussex, 1991-1993". Sussex Archaeological Collections. 134: 39–61.

- Seton-Williams, M. V. (1988). The road to El-Aguzein. Routledge. p. 32. ISBN 9780203038048. Retrieved 20 May 2020.

- Seymour, Ellie (2018). Secret Brighton (1 ed.). p. 157. ISBN 9782361952648.

- Sygrave, Jon (2016). "Whitehawk Camp: The impact of a modern city's expansion on a Neolithic causewayed enclosure, and a reassessment of the site and its surviving archive". Sussex Archaeological Collections. 154: 45–66.

- Whittle, Alasdair; Healy, Frances; Bayliss, Alex (2015) [2011]. "Gathering time: causewayed enclosures and the early Neolithic of southern Britain and Ireland". In Whittle, Alasdair; Healy, Frances; Bayliss, Alex (eds.). Gathering Time: Dating the Early Neolithic Enclosures of Southern Britain and Ireland. Oxford: Oxbow. pp. 1–16. ISBN 978-1-84217-425-8.

- Williamson, R.P. Ross (1930). "Excavations in Whitehawk Camp, Near Brighton". Sussex Archaeological Collections. 71: 56–96.