Weihaiwei under British rule

Weihaiwei, on the north-east coast of China, was a leased territory of the United Kingdom from 1898 until 1930. The capital was Port Edward (now known as "Weihai") The leased territory covered 288 square miles (750 km2)[1] and included the walled city of Port Edward, bay of Wei-hai-wei, Liu-kung Tao and a mainland area of 72 miles (116 km) of coastline running to a depth of 10 miles (16 km) inland. Together with Lüshunkou (Port Arthur) it controlled the entrance to the Gulf of Zhili and, thus, the seaward approaches to Beijing.[2]

Weihaiwei 威海衞 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1898–1930 | |||||||||

| |||||||||

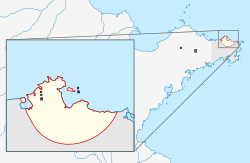

Location of Weihaiwei (blue) in 1921 | |||||||||

Location of Weihaiwei in Shandong | |||||||||

| Status | Leased territory of the United Kingdom | ||||||||

| Capital | Port Edward | ||||||||

| Common languages | |||||||||

| Government | |||||||||

• Monarch | Edward VII (first) George V (last) | ||||||||

• Commissioner | Sir Arthur Dorward (first) Sir Reginald Johnston (last) | ||||||||

| Historical era | New Imperialism | ||||||||

• Convention for the Lease of Weihaiwei | 1 July 1898 | ||||||||

• Convention for the Rendition of Weihaiwei | 30 September 1930 | ||||||||

| Currency | Chinese yuan Hong Kong dollar | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Weihaiwei under British rule | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 威海衞 | ||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 威海卫 | ||||||||||

| Literal meaning | powerful sea guard | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

Background to the British lease

The port of Weihaiwei was the base for the Beiyang Fleet (Northern Seas Fleet) during the Qing dynasty. In 1895, the Japanese captured it in the Battle of Weihaiwei, the last major battle of the First Sino-Japanese War. The Japanese withdrew in 1898.

After the Russia leased Port Arthur from China for 25 years in March 1898, the United Kingdom pressured the Chinese government into leasing Weihaiwei, with the terms of the treaty stating that it would remain in force for as long as the Russians were allowed to occupy Port Arthur. The British fleet took possession and raised its flag on 24 May 1898.[3] The port was primarily used as a summer anchorage for the Royal Navy's China Station and as a health resort. It also served as an occasional port of call for Royal Navy vessels in the Far East, well behind Hong Kong in the south. Other than for military matters, local administration was left under Chinese control, and the port itself remained a free port until 1923.

At the start of the Russo-Japanese War, the commander of the Royal Navy's China Station was initially ordered to withdraw his ships from Weihaiwei to avoid Britain being drawn into the conflict. However, fearing that Weihaiwei would be used as a safe haven by the Imperial Russian Navy, the Japanese government successfully pressured the British to return their fleet. During the War, the port was of importance as a telegraph and radio transmission station for correspondents covering the conflict, and was also a source of contraband shipping by blockade runners bringing supplies into Port Arthur.[2]

After the Japanese victory over Russia in 1905, Japan took possession of Port Arthur. Britain extended its lease over Weihaiwei for as long as the Japanese occupied Port Arthur.[3]

British rule in Weihaiwei

The War Office were responsible for the territory as it was envisaged that it would become a naval base similar to British Hong Kong. As such, the first Commissioners of Weihaiwei were appointed from the British Army and based themselves in Liu-kung Tao. At the beginning of the lease, the territory was administered by a Senior Naval Officer of the Royal Navy, Sir Edward Hobart Seymour. However a survey led by the Royal Engineers deemed that Weihaiwei was unsuitable for a major naval base or trading port.[4] In 1899, administration was transferred to a military and civil commissioner, firstly Arthur Dorward (1899–1901), then John Dodson Daintree (1901–1902), appointed by the War Office in London. The territorial garrison consisted of 200 British troops and a specially constituted Weihaiwei Regiment, officially the 1st Chinese Regiment, with British officers. In 1901, it was decided that this base should not be fortified and administration was transferred from the War Office to the Colonial Office which allowed for civilians to be appointed as the Commissioner.[4]

In 1909, the Hong Kong governor Sir Frederick Lugard, proposed that Britain return Weihaiwei to Chinese rule in return for perpetual rule of the New Territories of Hong Kong which had also been leased in 1898. This proposal was never adopted.[5]

Weihaiwei was not developed in the way that Hong Kong and other British colonies in the region were. This was because Shantung Province, of which Weihaiwei was part, was inside Germany's (and after World War I, Japan's) sphere of influence. It was normal practice for British colonies to be administered under the provisions of the British Settlements Act 1887. However, Weihaiwei was actually administered under the Foreign Jurisdiction Act 1890 which was the law which granted extraterritorial powers over British subjects in China and other countries in which Britain had extraterritorial rights. The reason for this was that as a leased territory, subject to rendition at any time, it was not considered appropriate to treat Weihaiwei as a full colony.

In exchange for recognizing British Weihaiwei, Germany demanded and received assurance from Britain through Arthur Balfour that Britain would recognize a German sphere in Shantung and not build a railway from Weihaiwei into the interior of Shantung province.[6]

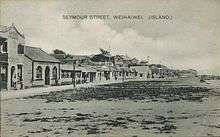

The nickname British sailors gave to this port was "Way High"; it was also referred to as Port Edward in English.

During British rule, residences, hospital, churches, tea houses, sports ground, post office, and a naval cemetery were constructed.[7]

Commissioners

| Commissioner of Weihaiwei

威海衞專員 | |

|---|---|

.svg.png) Commissioner's flag (1903–1930) | |

| Colonial Office | |

| Seat | Port Edward |

| Appointer | Monarch of the United Kingdom |

| Term length | At His Majesty's Pleasure |

| Formation | 1898 |

| First holder | Major-General Sir Arthur Robert Ford Dorward |

| Final holder | Sir Reginald Johnston |

| Abolished | 1930 |

The Commissioner of Weihaiwei (Chinese: 威海衞專員) was the head of government for the British leased territory of Weihaiwei between 1898 and 1930. Until 1902, the first Commissioners of Weihaiwei were members of the British Army before civilians were appointed to the role. A Civil Commissioner was appointed in February 1902 to administer the territory.[8] The post was held by Sir James Stewart Lockhart until 1921, where he oversaw the renaming of the civil seat of the Commissioner from Matou to Port Edward and started to develop the territory as a holiday resort for British expats.[4]

As the position was not a full Governorship, it afforded the holders more authority as they did not have to consult any territorial legislative or executive councils when making decisions or passing ordinances.[4] The Commissioner of Weihaiwei was also responsible for representing the territory overseas.[9]

After Lockhart, Arthur Powlett Blunt (1921–1923) and Walter Russell Brown (1923–1927) were appointed Commissioners in Weihaiwei. The last Commissioner was the outstanding sinologist Reginald Fleming Johnston (previously tutor to the last Chinese emperor) who served from 1927 to 1930.

Commissioners Flag

The Commissioners of Weihaiwei initially used a Union Jack with a Chinese imperial dragon from the flag of the Qing dynasty as their flag.[10][11] When the Lockhart arrived as the first civil commissioner, he wrote to the Colonial Office requesting that the dragon be replaced by Mandarin ducks as he felt it was inappropriate to use a Chinese national symbol on a British flag.[11] King Edward VII approved the new design as well as for the creation of a civil flag of Weihaiwei in 1903.[12]

List of Commissioners

Below is a list of the military and civilian Commissioners of Weihaiwei.

- 1898–1901 Major-General Sir Arthur Robert Ford Dorward[13]

- 1901–1902 Commander John Dodson Daintree, Royal Navy[14]

- 1902–1921 Sir James Stewart Lockhart

- 1921–1923 Captain Arthur Powlett Blunt (acting)[15]

- 1923–1927 Walter Russell Brown[16]

- 1927–1930 Sir Reginald Johnston[17]

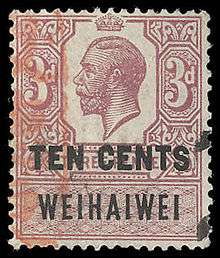

Postage and currency

No special postage stamps were ever issued for Weihaiwei. Just as in other treaty ports, Hong Kong stamps were used. From 1917, these were overprinted with the word "CHINA". Revenue stamps of Weihaiwei were issued from 1921. There were never any special coins or banknotes issued for circulation in Weihaiwei. The various currencies in circulation in China at the time were used; the Hong Kong dollar was also used.

Army and police

The Weihaiwei Regiment was formed in 1898 with Lt. Colonel Hamilton Bower as its first commanding officer and served in the Boxer Rebellion. The regiment was ordered to be totally disbanded in 1906[18] by Army Order No. 127 of 1906.[19]

Some of the soldiers were retained as a permanent police force with three British Colour Sergeants commissioned as police inspectors. In 1910 the police force comprised three European Inspectors and 55 Chinese Constables.[20] Previously the force had comprised one Chinese sergeant and seven constables under a District Officer.

During World War I the British recruited the Chinese Labor Corps in Weihaiwei to assist the war effort.

During the seamen's strike of 1922 in Hong Kong, the colonial government sent two European police officers to Weihaiwei in September of that year to recruit the first of about 50 Weihaiwei men as Royal Hong Kong Police constables. After completing six months' training in Weihaiwei, the recruits were posted to Hong Kong to maintain law and order in March 1923. The Weihaiwei policemen were known as the D Contingent in the HKP, and their service numbers were pre-fixed with letter "D" to differentiate them from the European "A", Indian "B" and Cantonese "C".[21]

At the end of 1927, the Chinese police were replaced by Indians.[22]

High Court

In 1903, the British established a High Court of Weihaiwei. The judges of the court were chosen from individuals serving as a judge or Crown Advocate of the British Supreme Court for China in Shanghai. The three judges of the court from 1903 to 1930 were:

- Frederick Samuel Augustus Bourne (1903–1916), Assistant Judge of HBM Supreme Court for China

- Hiram Parkes Wilkinson (1916–1925), Crown Advocate of HBM Supreme Court for China

- Peter Grain (1925–1930), Assistant Judge, and from 1927, Judge of HBM Supreme Court for China

The Commissioner could also exercise judicial powers if the judges of the court were not available.

Appeals from the High Court for Weihaiwei could be made to the Hong Kong Supreme Court. It appears that no appeal was ever heard in Hong Kong.[23]

Initially, the Crown Advocate for China, Hiram Parkes Wilkinson served as the Crown Advocate for Weihaiwei. When Wilkinson was appointed judge in 1916, Allan Mossop took over as Crown Advocate for Weihaiwei. Mossop later became Crown Advocate for China in 1926.

Return of Weihaiwei

Weihaiwei was returned to Chinese rule on 1 October 1930 under the egis of the final Commissioner of Weihaiwei Sir Reginald Johnston who previously had been a District Officer and a Magistrate in Weihaiwei. The last Commissioner of Weihaiwei flew the flag of the Republic of China alongside the Union Jack during the transitional day. Following the return of Weihaiwei to China, the Chinese replaced the British Commissioner role with their own version of the Commissioner as Weihaiwei became a Special Administrative Region of China;[24] later, the Monument to the Recovery of Weihaiwei was created. However, the Chinese government leased the island of Liu-kung Tao (Liugong Island) to the Royal Navy for ten years;[25] effective control came to an end following a Japanese military landing on 1 October 1940.[26]

See also

- China–United Kingdom relations

- British Empire

- Chinese Labor Corps - coolies were recruited from Weihaiwei during World War I

- British Hong Kong

- Portuguese Macau

- Guangzhouwan (1898–1945), French leased territory in China administered as part of Indochina

Notes

- pp.462-463 Hutchings, Graham Modern China: A Guide to a Century of Change Harvard University Press, 1 Sep 2003

- Kowner, Rotem (2006). Historical Dictionary of the Russo-Japanese War. The Scarecrow Press. ISBN 0-8108-4927-5. p. 417-418.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. 28 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 494–495.

- Nield, Robert (2015). China's Foreign Places: The Foreign Presence in China in the Treaty Port Era, 1840–1943. Hong Kong University Press. pp. 259–264. ISBN 978-9888139286.

- Vines, Stephen (30 June 1997). "How Britain lost chance to keep its last major colony". The Independent.

- p. 9 Otte, T. E. "Wei-Ah-Wee?"?: Britain at Weihaiwei, 1898-1930 in British Naval Strategy East of Suez, 1900-2000: Influences and Actions edited by Greg Kennedy Routledge, 25 Aug. 2014

- "VELTRA tours & activities, fun things to do".

- "No. 27403". The London Gazette. 4 February 1902. p. 709.

- "British Commissioner of Weihaiwei at reception at Wang Tien Chiao". University of Bristol. 1903. Retrieved 18 May 2017.

- "Foreign colonies in China". Flags of the World. Retrieved 12 May 2017.

- "The Colours of the Fleet". The Flag Institute. Retrieved 12 May 2017.

- French, Paul (30 April 2009). "Flags of British Weihaiwei". China Rhyming. Retrieved 25 April 2017.

- "No. 27352". The London Gazette. 6 September 1901. p. 5875.

- "Quingdao and Weihaiwei Masonic Halls" (PDF). Freemasons. Retrieved 12 May 2017. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "CENTRAL CHANCERY OF THE ORDERS OF KNIGHTHOOD" (PDF). The Edinburgh Gazette. 23 January 1923. Retrieved 12 May 2017.

- Henige, David (1970). Colonial Governors. University of Wisconsin Press. p. 187.

- "Scottish Mandarin". Project MUSE. 22 October 1924. Retrieved 12 May 2017.

- p. 56 Airlie, Shiona Scottish Mandarin: The Life and Times of Sir Reginald Johnston Hong Kong University Press, 1 October 2012

- http://www.abandonedbritish-chinesesoldiers.org.uk/the-forgotten-history/

- p.83 Johnson

- "News". www.police.gov.hk. Retrieved 9 April 2018.

- http://www.legco.gov.hk/1926/h261228.pdf

- See Tan, Carol G.S. (2008) British Rule in China: Law and Justice in Weihaiwei 1898–1930. London: Wildy, Simmonds & Hill for a comprehensive history of British justice in the Weihaiwei leased territory.

- Teresa Poole (3 October 1996). "perfect goodbye Hong Kong dreams of Gun salutes and grateful thanks . . . the perfect goodbye". The Independent. Retrieved 12 May 2017.

- pp. 32-33 Schwankert, Steven R. Poseidon: China's Secret Salvage of Britain's Lost Submarine Hong Kong University Press, 1 October 2013

- "Weihaiwai Withdrawal". nlb.gov.sg. Retrieved 9 April 2018.

Further reading

- Airlie, Shiona (2010). Thistle and Bamboo: The Life and Times of Sir James Stewart Lockhart. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press. ISBN 9789888028924.

- Atwell, Pamela (1985). British Mandarins and Chinese Reformers. Hong Kong: Oxford University Press.

External links

- . New International Encyclopedia. 1905.