WWV (radio station)

WWV is a shortwave (also known as "high frequency" (HF)) radio station, located near Fort Collins, Colorado. It is best known for its continuous time signal broadcasts begun in 1945, and is also used to establish official United States government frequency standards, with transmitters operating on 2.5, 5, 10, 15, and 20 MHz.[1] WWV is operated by the U.S. National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), under the oversight of its Time and Frequency Division, which is part of NIST's Physical Measurement Laboratory based in Gaithersburg, Maryland.[2]

WWV was first established in 1919 by the Bureau of Standards in Washington, D.C. It has been described as the oldest continuously-operating radio station in the United States,[3] and NIST celebrated WWV's centennial on October 1, 2019.[4]

In 1931 the station relocated to the first of three suburban Maryland sites, before moving to its current location near Fort Collins in 1966. WWV shares this site with longwave (also known as "low frequency" (LF)) station WWVB, which transmits carrier and time code (no voice) at 60 kHz. NIST also operates the similarly structured WWVH on Kauai, Hawaii. Both WWV and WWVH announce the Coordinated Universal Time each minute, and make other recorded announcements of general interest on an hourly schedule, including the Global Positioning System (GPS) satellite constellation status. Because they simultaneously transmit on the same frequencies, WWV uses a male voice in order to differentiate itself from WWVH, which uses a female voice.

Service

Since 1945 WWV has disseminated "official U.S. time", as provided by government entities such as NIST and the United States Naval Observatory (USNO), to ensure that uniform time is maintained throughout the United States and around the world. WWV provides a public service by making time information readily available at all hours and at no monetary charge beyond the cost of the receiving equipment.

The time signals generated by WWV allow time-keeping devices such as radio-controlled clocks to automatically maintain accurate time without the need for manual adjustment. These time signals are used by commercial and institutional interests where accuracy is essential and time plays a vital role in daily operations - including shipping, transport, technology, research, education, military, public safety and telecommunications. It is of particular importance in broadcasting, whether it be commercial, public, or private interests such as amateur radio operators.

Transmission system

| WWV antenna coordinates (WGS84) | |

|---|---|

| 2.5 MHz | 40°40′55.0″N 105°02′33.6″W |

| 5 MHz | 40°40′41.9″N 105°02′27.2″W |

| 10 MHz | 40°40′47.7″N 105°02′27.4″W |

| 15 MHz | 40°40′44.8″N 105°02′26.9″W |

| 20 MHz | 40°40′52.8″N 105°02′30.9″W |

| 25 MHz | 40°40′50.8″N 105°02′32.6″W |

WWV broadcasts over six transmitters, each one dedicated for use on a single frequency. The transmitting frequencies and time signals of WWV, WWVB and WWVH, along with the four atomic (cesium) clocks from which their time signals are derived, are maintained by NIST's Time and Frequency Division, which is based in nearby Boulder, Colorado.[2] WWVB's carrier frequency is maintained to an accuracy of 1 part in 1014 and can be used as a frequency reference.[5][6][7] The broadcast time is accurate to within 100 ns of UTC and 20 ns of the national time standard.[8][5]

The transmitters for 2.5 MHz, 20 MHz, and the experimental 25 MHz put out an ERP of 2.5 kW, while those for the other three frequencies use 10 kW of ERP.[9] Each transmitter is connected to a dedicated antenna, which has a height corresponding to approximately one-half of its signal's wavelength, and the signal radiation patterns from each antenna are omnidirectional. The top half of each antenna tower contains a quarter-wavelength radiating element, and the bottom half uses nine guy wires, connected to the midpoint of the tower and sloped at one-to-one from the ground—with a length of √2/4 times the wavelength—as additional radiating elements.[10]

Telephone service

WWV's time signal can also be accessed by telephone by calling +1 (303) 499-7111 (WWV) or +1 (808) 335-4363 for WWVH. An equivalent time service operated by the United States Naval Observatory can be accessed by calling +1 (202) 762-1401 (Washington, D.C.). Telephone calls are limited to 2 minutes and 35 seconds, and the signal is delayed by an average of 30 milliseconds due to telephone network propagation time.[11]

Broadcast format

On top of the standard carrier frequencies, WWV carries additional information using standard double-sideband amplitude modulation. WWV's transmissions follow a regular pattern repeating each minute. They are coordinated with its sister station WWVH to limit interference between them. Because they are so similar, both are described here.

| Second | WWV | WWVH |

|---|---|---|

| 0–1 | Minute beep (0.8 s) | |

| 1–45 | Standard tone or voice announcement | |

| 45–52.5 | Silence (except tick) | Voice time announcement |

| 52.5–60 | Voice time announcement | Silence (except tick) |

Date and time

WWV transmits the date and exact time as follows:

- English-language voice announcements of time.

- Binary-coded decimal time code of date and time, transmitted as varying length pulses of 100 Hz tone, one bit per second.[12]

In both cases the transmitted time is given in Coordinated Universal Time (UTC).

Per-second ticks and minute markers

WWV transmits audio "ticks" once per second, to allow for accurate manual clock synchronization. These ticks are always transmitted, even during voice announcements and silent periods. Each tick begins on the second, lasts 5 ms and consists of 5 cycles of a 1000 Hz sine wave. To make the tick stand out more, all other signals are suppressed for 40 ms, from 10 ms before the second until 30 ms after (25 ms after the tick). As an exception, no tick (and no silent interval) is transmitted at 29 or 59 seconds past the minute. In the event of a leap second, no tick is transmitted during second 60 of the minute, either.[13]

On the minute, the tick is extended to a 0.8 second long beep, followed by 0.2 s of silence. On the hour, this minute pulse is transmitted at 1500 Hz rather than 1000 Hz. The beginning of the tone corresponds to the start of the minute.[14]

Between seconds one and sixteen inclusive past the minute, the current difference between UTC and UT1 is transmitted by doubling some of the once-per-second ticks, transmitting a second tick 100 ms after the first. (The second tick preempts other transmissions, but does not get a silent zone.[13]) The absolute value of this difference, in tenths of a second, is determined by the number of doubled ticks. The sign is determined by the position; if the doubled ticks begin at second one, UT1 is ahead of UTC; if they begin at second nine, UT1 is behind UTC.[14]

WWVH transmits similar 5 ms ticks, but they are sent as 6 cycles of 1200 Hz. The minute beep is also 1200 Hz, except on the hour, when it is 1500 Hz.

The ticks and minute tones are transmitted at 100% modulation (0 dBc).[9]

Voice time announcements

Voice announcements of time of day are made at the end of every minute, giving the time of the following minute beep. The format for the voice announcement is, "At the tone, X hour(s), Y minute(s), Coordinated Universal Time." The announcement is in a male voice and begins 7.5 seconds before the minute tone.

WWVH makes an identical time announcement, starting 15 seconds before the minute tone, in a female voice.

When voice announcements were first instituted, they were phrased as follows: "National Bureau of Standards, WWV; when the tone returns, Eastern Standard Time is [time in 12-hour format]."[15] After the 1967 switch to GMT, the announcement changed to "National Bureau of Standards, WWV, Fort Collins, Colorado; next tone begins at X hours, Y minute(s), Greenwich Mean Time."[16] However, this format would be short-lived. The announcement was changed again to the current format in 1971. "At the tone, X hour(s), Y minute(s), Greenwich Mean Time." The name "Greenwich Mean Time" was changed to "Coordinated Universal Time" in 1974.[17]

Voice time announcements are sent at 75% modulation (−1.25 dBc), i.e., the carrier varies between 25% and 175% of nominal power.[9]

Other voice announcements

WWV transmits the following 44-second voice announcements (in lieu of the standard frequency tones) on an hourly schedule:[14]

- A station identification at :00 and :30 past each hour;

- marine storm warnings, provided by the National Weather Service, for the Atlantic Ocean at :08 and :09 minutes past, and for the Pacific Ocean at :10 past; As of February 7, 2019, these have been replaced with a message indicating their discontinuation.

- at :14 and :15 past, GPS satellite health reports from the Coast Guard Navigation Center;

- at :18 past, a special "geophysical alert" report from NOAA is transmitted, containing information on solar activity and shortwave radio propagation conditions. These particular alerts were to be discontinued on September 6, 2011.[18] However, as of June 17, 2011, WWV is announcing at :18 past that the decision has been retracted and that the geophysical alert reports "will continue for the foreseeable future". Here is an example of this announcement from May 24, 2018 at 0905 UTC: "Solar-terrestrial indices for 23 May follow. Solar flux 73 and estimated planetary A-index 9. The estimated planetary K-index at 0900 UTC on 24 May was 1. No space weather storms were observed for the past 24 hours. No space weather storms are predicted for the next 24 hours."[19]

- at :10 past the hour WWV transmits a Department of Defense message if any exists; WWVH does the same at :50 past the hour.[20]

Additional time slots are normally transmitted as a standard frequency tone, but can be preempted by voice messages if necessary:

- At :04 and :16 past the hour, NIST broadcasts any announcements regarding a manual change in the operation of WWV and WWVH, such as leap second announcements. These minutes are marked in the broadcast schedule as "NIST Reserved". When not used, a 500 Hz tone is broadcast. Prior to the shutdown of the OMEGA navigation system in 1997, an OMEGA status report was broadcast at :16 past the hour.

- Minute 11 is used for additional storm warnings if necessary. If not, a 600 Hz tone is transmitted.

WWVH transmits the same information on a different schedule. WWV and WWVH's voice announcements are timed to avoid crosstalk; WWV airs dead air when WWVH airs voice announcements, and vice versa. WWVH's storm warnings cover the area around the Hawaiian islands and the Far East rather than North America.

| Minute | WWV | WWVH | Minute | WWV | WWVH | Minute | WWV | WWVH | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 00 | Station identification | Silence | 20 | 500 Hz | 600 Hz | 40 | 500 Hz | 600 Hz | ||

| 01 | 600 Hz | 440 Hz | 21 | 600 Hz | 500 Hz | 41 | 600 Hz | 500 Hz | ||

| 02 | 440 Hz | 600 Hz | 22 | 500 Hz | 600 Hz | 42 | 500 Hz | 600 Hz | ||

| 03 | 600 Hz | (NIST reserved) | 23 | 600 Hz | 500 Hz | 43 | Silence | GPS status | ||

| 04 | (NIST reserved) | 600 Hz | 24 | 500 Hz | 600 Hz | 44 | Silence | GPS status | ||

| 05 | 600 Hz | 500 Hz | 25 | 600 Hz | 500 Hz | 45 | Silence | Geophysical alerts | ||

| 06 | 500 Hz | 600 Hz | 26 | 500 Hz | 600 Hz | 46 | Silence | 600 Hz | ||

| 07 | 600 Hz | 500 Hz | 27 | 600 Hz | 500 Hz | 47 | Silence | (NIST reserved) | ||

| 08 | North Atlantic storm warnings | Silence | 28 | 500 Hz | 600 Hz | 48 | Silence | West Pacific storm warnings | ||

| 09 | North Atlantic storm warnings | Silence | 29 | Silence | Station identification | 49 | Silence | East Pacific storm warnings | ||

| 10 | Northeast Pacific storm warnings | Silence | 30 | Station identification | Silence | 50 | Silence | South Pacific storm warnings | ||

| 11 | (Additional storm warnings) | Silence | 31 | 600 Hz | 500 Hz | 51 | Silence | North Pacific storm warnings | ||

| 12 | 500 Hz | 600 Hz | 32 | 500 Hz | 600 Hz | 52 | Silence | (Additional storm warnings) | ||

| 13 | 600 Hz | 500 Hz | 33 | 600 Hz | 500 Hz | 53 | 600 Hz | 500 Hz | ||

| 14 | GPS status | Silence | 34 | 500 Hz | 600 Hz | 54 | 500 Hz | 600 Hz | ||

| 15 | GPS status | Silence | 35 | 600 Hz | 500 Hz | 55 | 600 Hz | 500 Hz | ||

| 16 | (NIST reserved) | Silence | 36 | 500 Hz | 600 Hz | 56 | 500 Hz | 600 Hz | ||

| 17 | 600 Hz | Silence | 37 | 600 Hz | 500 Hz | 57 | 600 Hz | 500 Hz | ||

| 18 | Geophysical alerts | Silence | 38 | 500 Hz | 600 Hz | 58 | 500 Hz | 600 Hz | ||

| 19 | Geophysical alerts | Silence | 39 | 600 Hz | 500 Hz | 59 | Silence | Station identification |

Half-hourly station identification announcement

WWV identifies itself twice each hour, at 0 and 30 minutes past the hour. The text of the identification is as follows:

National Institute of Standards and Technology time: this is Radio Station WWV, Fort Collins Colorado, broadcasting on internationally allocated standard carrier frequencies of two-point-five, five, ten, fifteen, and twenty megahertz, providing time of day, standard time interval, and other related information. Inquiries regarding these transmissions may be directed to the National Institute of Standards and Technology, Radio Station WWV, 2000 East County Road 58, Fort Collins, Colorado, 80524.

WWV accepts reception reports sent to the address mentioned in the station ID, and responds with QSL cards.

Standard audio tone frequencies

WWV and WWVH transmit 44 seconds of audio tones during most minutes. They begin after the 1-second minute mark and continues until the beginning of the WWVH time announcement 45 seconds after the minute.

Even-numbered minutes (except for minute 2) transmit 500 Hz, while 600 Hz is heard during odd-numbered minutes. The tone is interrupted for 40 ms each second by the second ticks. WWVH is similar, but exchanges the two tones.

WWV also transmits a 440 Hz tone, a pitch commonly used in music (A440, the musical note A above middle C) during minute 2 of each hour, except for the first hour of the UTC day. Since the 440 Hz tone is only transmitted once per hour, many chart recorders may use this tone to mark off each hour of the day, and likewise, the omission of the 440 Hz tone once per day can be used to mark off each twenty-four-hour period. WWVH transmits the same tone during minute 1 of each hour.

No tone is transmitted during voice announcements from either WWV or WWVH; the latter causes WWV to transmit no tone during minutes 43 through 51 (inclusive) and minutes 29 and 59 of each hour.[14] Likewise, WWVH transmits no tone during minutes 0, 8, 9, 10, 14 through 19, and 30.

Audio tones and other voice announcements are sent at 50% modulation (−3 dBc).[9]

Digital time code

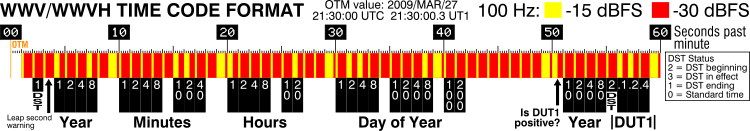

Time of day is also continuously transmitted using a digital time code, interpretable by radio-controlled clocks. The time code uses a 100 Hz subcarrier of the main signal. That is, it is an additional low-level 100 Hz tone added to the other AM audio signals.

This code is similar to, and has the same framework as, the IRIG H time code and the time code that WWVB transmits, except the individual fields of the code are rearranged and are transmitted with the least significant bit sent first. Like the IRIG timecode, the time transmitted is the time of the start of the minute. Also like the IRIG timecode, numeric data (minute, hour, day of year, and last two digits of year) are sent in binary-coded decimal (BCD) format rather than as simple binary integers: Each decimal digit is sent as two, three, or four bits (depending on its possible range of values).

Bit encoding

The 100 Hz subcarrier is transmitted at −15 dBc (18% modulation) beginning at 30 ms from the start of the second (the first 30 ms are reserved for the seconds tick), and then reduced by 15 dB (to −30 dBc, 3% modulation) at one of three times within the second. The duration of the high amplitude 100 Hz subcarrier encodes a data bit of 0, a data bit of 1, or a "marker", as follows:

- If the subcarrier is reduced 800 ms past the second, this indicates a "marker."

- If the subcarrier is reduced 500 ms past the second, this indicates a data bit with value one.

- If the subcarrier is reduced 200 ms past the second, this indicates a data bit with value zero.

A single bit or marker is sent in this way in every second of each minute except the first (second :00). The first second of each minute is reserved for the minute marker, previously described.

In the diagram above, the red and yellow bars indicate the presence of the 100 Hz subcarrier, with yellow representing the higher strength subcarrier (−15 dB referenced to 100% modulation) and red the lower strength subcarrier (−30 dB referenced to 100% modulation). The widest yellow bars represent the markers, the narrowest represent data bits with value 0, and those of intermediate width represent data bits with value 1.

Interpretation

It takes one minute to transmit a complete time code. Most of the bits encode UTC time, day of year, year of century, and UT1 correction up to ±0.7 s.

Like the WWVB time code, only the tens and units digits of the year are transmitted; unlike the WWVB time code, there is no direct indication for leap year. Thus, receivers assuming that year 00 is a leap year (correct for year 2000) will be incorrect in the year 2100. On the other hand, receivers that assume year 00 is not a leap year will be correct for 2001 through 2399.

The table below shows the interpretation of each bit, with the "Ex" column being the values from the example above.

| Bit | Weight | Meaning | Ex | Bit | Weight | Meaning | Ex | Bit | Weight | Meaning | Ex | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| :00 | No 100 Hz (minute mark) | :20 | 1 | Hours Example: 21 | 1 | :40 | 100 | Day of year (cont.) | 0 | ||||

| :01 | 0 | Unused, always 0. | 0 | :21 | 2 | 0 | :41 | 200 | 0 | ||||

| :02 | DST1 | DST status at 00:00Z today Example: No DST at 00:00Z | 0 | :22 | 4 | 0 | :42 | 0 | Unused, always 0. | 0 | |||

| :03 | LSW | Leap second at end of month | 0 | :23 | 8 | 0 | :43 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| :04 | 1 | Units digit of year Example: 9 | 1 | :24 | 0 | 0 | :44 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| :05 | 2 | 0 | :25 | 10 | 0 | :45 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| :06 | 4 | 0 | :26 | 20 | 1 | :46 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| :07 | 8 | 1 | :27 | 0 | Unused, always 0. | 0 | :47 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| :08 | 0 | Unused, always 0. | 0 | :28 | 0 | 0 | :48 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| :09 | P1 | Marker | M | :29 | P3 | Marker | M | :49 | P5 | Marker | M | ||

| :10 | 1 | Minutes Example: 30 | 0 | :30 | 1 | Day of year 1=January 1, 32=February 1, etc. Example: 86 | 0 | :50 | + | DUT1 sign (1=positive) | 1 | ||

| :11 | 2 | 0 | :31 | 2 | 1 | :51 | 10 | Tens digit of year Example: 0 | 0 | ||||

| :12 | 4 | 0 | :32 | 4 | 1 | :52 | 20 | 0 | |||||

| :13 | 8 | 0 | :33 | 8 | 0 | :53 | 40 | 0 | |||||

| :14 | 0 | 0 | :34 | 0 | 0 | :54 | 80 | 0 | |||||

| :15 | 10 | 1 | :35 | 10 | 0 | :55 | DST2 | DST status at 24:00Z today Example: No DST at 24:00Z today | 0 | ||||

| :16 | 20 | 1 | :36 | 20 | 0 | :56 | 0.1 | DUT1 magnitude (0 to 0.7 s). DUT1 = UT1−UTC. Example: 0.3 s | 1 | ||||

| :17 | 40 | 0 | :37 | 40 | 0 | :57 | 0.2 | 1 | |||||

| :18 | 0 | Unused, always 0. | 0 | :38 | 80 | 1 | :58 | 0.4 | 0 | ||||

| :19 | P2 | Marker | M | :39 | P4 | Marker | M | :59 | P0 | Marker | M | ||

The example shown encodes day 86 (March 27) of 2009, at 21:30:00 UTC. DUT1 is +0.3, so UT1 is 21:30:00.3. Daylight Saving Time was not in effect at the previous 00:00 UTC (DST1=0), and will not be in effect at the next 00:00 UTC (DST2=0). There is no leap second scheduled (LSW=0). The day of year normally runs from 1 (January 1) through 365 (December 31), but in leap years, December 31 would be day 366, and day 86 would be March 26 instead of March 27.

Daylight saving time and leap seconds

The time code contains three bits announcing daylight saving time (DST) changes and imminent leap seconds.

- Bit :03 is set near the beginning of the month which is scheduled to end in a leap second. It is cleared when the leap second occurs.

- Bit :55 (DST2) is set at UTC midnight just before DST comes into effect. It is cleared at UTC midnight just before standard time resumes.

- Bit :02 (DST1) is set at UTC midnight just after DST comes into effect, and cleared at UTC midnight just after standard time resumes.

If the DST1 and DST2 bits differ, DST is changing during the current UTC day, at the next 02:00 local time. Before the next 02:00 local time after that, the bits will be the same. Each change in the DST bits happens at 00:00 UTC and so will first be received in the mainland United States between 16:00 (PST) and 20:00 (EDT), depending on local time zone and on whether DST is about to begin or end. A receiver in the Eastern time zone (UTC−5) must therefore correctly receive the "DST is changing" indication within the seven hours before DST begins, and six hours before DST ends, if it is to change the local time display at the correct time. Receivers in the Central, Mountain, and Pacific time zones have one, two, and three more hours of advance notice, respectively.

During a leap second, a binary zero is transmitted in the time code;[21] in this case, the minute will not be preceded by a marker.

History

Establishment

.jpg)

The earliest formal record of WWV's existence is in the October 1, 1919 issue of the Department of Commerce's Radio Service Bulletin, where it is listed as a new "experimental station"[23] assigned to the Bureau of Standards in Washington, D.C, with the randomly issued call letters of WWV.[24] However, there were also earlier reports of radio demonstrations by the Bureau, starting the previous February.[25][26][27]

As of May 1920 the Bureau's Radio Laboratory was reported to be conducting weekly Friday evening concerts from 8:30 to 11:00, transmitting on 600 kHz.[28] That same month, the Bureau demonstrated a portable radio receiver, called the "portaphone", which was said to be capable of receiving broadcast programs up to 15 miles (24 km) away.[22] A newspaper article the following August reported that the weekly concerts could be heard up to 100 miles (160 km) from Washington. It also noted that "The bureau has been experimenting with the wireless music for several months, and has reached such an advanced stage of development that further investigation to them is useless, and they are going to discontinue the concerts."[29] However, the station continued to make occasional broadcasts, and in January 1921 a new distance record was announced when a listener in Chattanooga, Tennessee reported hearing the "jazzy waves whirling out from the Bureau of Standards".[30]

On December 15, 1920, WWV began broadcasting 500-word "Daily Radio Marketgrams", prepared by the U.S. Bureau of Markets, in Morse code on 750 kHz, which reportedly could be heard up to 200 miles (320 km) from Washington.[31] However, on April 15, 1921 responsibility for the reports was transferred to four stations operated by the Post Office Department, including its WWX in Washington, D.C.[32]

Standard frequency transmissions

At the end of 1922, WWV's purpose shifted to broadcasting standard frequency signals. These were an important aid to broadcasting and amateur stations, because their equipment limitations at the time meant they had difficulty staying on their assigned frequencies. Testing began on January 29, 1923.[33] Regularly scheduled operations began on March 6, 1923, initially consisting of seven transmitting frequencies ranging from 550 to 1500 kHz (wavelengths of 545 to 200 meters).[34] The frequencies were accurate to "better than three-tenths of one percent".[35] At first, the transmitter had to be manually switched from one frequency to the next, using a wavemeter. The first quartz resonators (that stabilized the frequency generating oscillators) were invented in the mid-1920s, and they greatly improved the accuracy of WWV's frequency broadcasts.[10]

In 1926, WWV was nearly shut down. Its signal could only cover the eastern half of the United States, and other stations located in Minneapolis and at Stanford University and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology were slowly making WWV redundant. The station's impending shutdown was announced in 1926, but it was saved by a flood of protests from citizens who relied on the service. Later, in 1931, WWV underwent an upgrade. Its transmitter, now directly controlled by a quartz oscillator, was moved to College Park, Maryland. Broadcasts began on 5 MHz. A year later, the station was moved again, to Department of Agriculture land in Beltsville, Maryland.[10] Broadcasts were added on 10 and 15 MHz, power was increased, and time signals, an A440 tone, and ionosphere reports were all added to the broadcast in June 1937.[10]

WWV was nearly destroyed by a fire on November 6, 1940. The frequency and transmitting equipment was recovered, and the station was back on the air (with reduced power) on November 11. Congress funded a new station in July 1941, and it was built 5 kilometres (3.1 mi) south of the former location, still referred to as Beltsville (although in 1961 the name used for the transmitter location would be changed to Greenbelt, Maryland).[10] WWV resumed normal broadcasts on 2.5, 5, 10, and 15 MHz on August 1, 1943.[33]

Time signal transmissions

Beginning in 1913 the primary official time station broadcasting in the eastern United States was the Navy's NAA in Arlington, Virginia, however NAA was decommissioned in 1941. WWV began broadcasting second pulses in 1937, but initially these were not tied to actual time. In June 1944, the United States Naval Observatory allowed WWV to use the USNO's clock as a source for its time signals. Over a year later, in October 1945, WWV broadcast Morse code time announcements every five minutes. Voice announcements started on January 1, 1950, and were broadcast every five minutes. Audio frequencies of 600 Hz and 440 Hz were employed during alternating minutes. By this time, WWV was broadcasting on 2.5, 5, 10, 15, 20, 25, 30, and 35 MHz. The 30 and 35 MHz broadcasts ended in 1953.[10]

A binary-coded decimal time code began testing in 1960, and became permanent in 1961. This "NASA time code" was modulated onto a 1,000 Hz audio tone at 100 Hz, sounding somewhat like a monotonous repeated "baaga-bong".[10] The code was also described as sounding like a "buzz-saw". On July 1, 1971, the time code's broadcast was changed to the present 100 Hz subcarrier, which is inaudible when using a normal radio (but can be heard using headphones or recorded using a chart recorder).[36]

WWV moved to its present location near Fort Collins on December 1, 1966,[37] enabling better reception of its signal throughout the continental United States. WWVB signed on in that location three years earlier. In April 1967, WWV stopped using the local time of the transmitter site (Eastern Time until 1966, and Mountain Time afterwards) and switched to broadcasting Greenwich Mean Time or GMT. The station switched again, to Coordinated Universal Time (UTC), in 1974.[10]

The 20 and 25 MHz broadcasts were discontinued in 1977, but the 20 MHz broadcast was reinstated the next year.[10] Starting on April 4, 2014, the 25 MHz signal was back on the air in an 'experimental' mode.[38]

The voice used on WWV was that of professional broadcaster Don Elliott Heald until August 13, 1991, when equipment changes required re-recording the announcer's voice. The one used at that time was that of another professional broadcaster, John Doyle, but was soon switched to the voice of KSFO morning host Lee Rodgers, since then John Doyle's voice has been returned to the broadcast.[39][40]

WWV, along with WWVB and WWVH, was recommended for defunding and elimination in NIST's Fiscal Year 2019 budget request.[41] However, the final 2019 NIST budget preserved funding for the three stations.[42]

WWV and Sputnik

WWV's 20 MHz signal was used for a unique purpose in 1958: to track the disintegration of Russian satellite Sputnik 1 after the craft's onboard electronics failed. Dr. John D. Kraus, a professor at Ohio State University, knew that a meteor entering the upper atmosphere leaves in its wake a small amount of ionized air. This air reflects a stray radio signal back to Earth, strengthening the signal at the surface for a few seconds. This effect is known as meteor scatter. Dr. Kraus figured that what was left of Sputnik would exhibit the same effect, but on a larger scale. His prediction was correct; WWV's signal was noticeably strengthened for durations lasting over a minute. In addition, the strengthening came from a direction and at a time of day that agreed with predictions of the paths of Sputnik's last orbits. Using this information, Dr. Kraus was able to draw up a complete timeline of Sputnik's disintegration. In particular, he observed that satellites do not fall as one unit; instead, the spacecraft broke up into its component parts as it moved closer to Earth.[43][44]

See also

- CHU – Canadian shortwave time broadcast station

- DCF77 – Longwave time broadcast station in Germany

- Radio clock – time-signal receivers

| Station | Year in service |

Year out of service |

Radio frequencies |

Audio frequencies |

Musical pitch |

Time intervals |

Time signals |

UT2 correction |

Propagation forecasts |

Geophysical alerts |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WWV | 1923 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |

| WWVH | 1948 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||

| WWVB | 1963 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |||||

| WWVL | 1963 | 1972 | ✔ |

References

- Transmissions at 25 MHz were last conducted in 2014 on an experimental basis. They were discontinued due to Solar flux levels dropping below that needed for propagation at upper HF/shortwave frequencies. This deterioration began in the latter years of the 24th Solar cycle.

- "Physical Measurement Laboratory: Time and Frequency Division". NIST.gov. Retrieved 22 December 2018.

- "What Closing A Government Radio Station Would Mean For Your Clocks" (transcript), Weekend Edition Saturday, August 25, 2018 (NPR.com)

- "NIST Radio Station WWV 100-year Anniversary" (NIST.gov)

- Lombardi, Michael A.; Nelson, Glenn K. (12 March 2014). "WWVB: A Half Century of Delivering Accurate Frequency and Time by Radio" (PDF). Journal of Research of the National Institute of Standards and Technology. 119: 25–54. doi:10.6028/jres.119.004. PMC 4487279. PMID 26601026.

The stability of the time scale now allows the station time to be typically kept within ±0.02 μs (20 ns) of the national time standard in Boulder, and to agree to within 1 × 10−14 in frequency.

- "Timing, Precision Frequency Reference". www.ko4bb.com. Retrieved 2018-12-22.

- w2aew (8 August 2012). #58: How to zero-beat WWV to check or adjust a Frequency Counter's accuracy. Retrieved 2018-12-22.

- Novick, Andrew (2016-12-05). "NIST Radio Broadcasts Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)". (NIST.gov). Retrieved 2018-12-22.

The time is kept to within less than 0.0001 milliseconds of Coordinated Universal Time (UTC)

- "Radio Station WWV". (NIST.gov). Retrieved 2018-12-22. (includes description of 25 MHz broadcast)

- Nelson, Glenn; Michael Lombardi; Dean Okayama (January 2005). "NIST Time and Frequency Stations: WWV, WWVH and WWVB (NIST Special Publication 250-67)" (PDF). (NIST.gov). Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "Telephone Time-of-Day Service". (NIST.gov). Retrieved 2018-12-22.

- "WWV and WWVH Digital Time Code and Broadcast Format", December 05, 2016 (NIST.gov)

- "Leap Second 2005" (audio recordings of WWV during a leap second) by John Ackermann (febo.com)

- "Information Transmitted by WWV and WWVH". (NIST.gov). Retrieved 2018-12-22.

- "NBS Standard Frequencies and Time Signals (Letter Circular 1023)" (PDF). (NIST.gov). July 1956. Retrieved 2018-12-22.

- "NBS Frequency and Time Broadcast Services (Special Publication 236)" (PDF). (NIST.gov). 1968. Retrieved 2018-12-22.

- Viezbicke, P (July 1971). "NBS Frequency and Broadcast Services (Special Publication 236, 1971 Edition)" (PDF). Washington, D.C: US Government Printing Office. Retrieved 2018-12-22.

- "Space Weather Prediction Center to Discontinue Broadcasts on WWV and WWVH". American Radio Relay League (ARRL.org). 25 April 2011. Retrieved 22 December 2018.

- "Geophysical Alert - WWV text". Retrieved 2018-05-24. NOAA / NWS Space Weather Prediction Center (NOAA.gov)

- "Department of Defense to Transmit Interoperability Exercise Info via WWV/WWVH", March 29, 2019 (ARRL.org)

- Lombardi, Michael (January 2002). "NIST Time and Frequency Services (NIST Special Publication 432)" (PDF). (NIST.gov). p. 21. Retrieved 2018-12-22.

- "The Portaphone—A Wireless Set for Dance Music or the Day's News" by Herbert T. Wade, Scientific American, May 22, 1920, page 571.

- "New Stations: Government Stations", Radio Service Bulletin, October 1, 1919, page 4.

- WWV received its call letters from a block of call signs that the Department of Commerce, which regulated radio at this time, had issued to government stations—two months previously it assigned WWG, WWO, WWU, WWQ and WWX to five Post Office Department stations ("New Stations: Government Stations", Radio Service Bulletin, August 1, 1919, page 4). WWV is one of a small number of radio stations west of the Mississippi River with a call sign beginning with W instead of K, as the original call was kept when the station moved to Colorado. As a government station, WWV, does not fall within the FCC's jurisdiction with respect to call signs, and an FCC regulation reserves the call signs WWV, WWVB through WWVI, WWVL and WWVS for "standard frequency" stations ("Title 47:Subpart D:§ 2.302: Call Signs", Code of Federal Regulations, Government Printing Office).

- "Awed Visitors Listen to 'Pretty Baby' Played by Wireless Phonograph", Washington Times, February 26, 1919, page 3.

- "Music By Radio Now Fact" by J. Maell, Washington Times, July 31, 1919, page 15.

- An Almost Unlimited Field For Radio Telephony", Radio News, February 1920, page 434.

- "13 The Transmission of Music by Radio" by S. W. Stratton, Technical News Bulletin no. 38, Bureau of Standards, June 4, 1920, pages 8-9.

- "'Picking' Tunes From Air Nightly Pastime With Wireless Amateurs", Washington Times, August 8, 1920, page 26.

- "Hear D.C. Radio Music in Tenn.", Washington Times, January 17, 1921, page 1.

- "Daily Radio Marketgrams", The Wireless Age, April 1921, page 8.

- "Radio Market News Service", QST, July 1921, page 24.

- Beers, Yardley. "WWV Moves to Colorado: In Two Parts - Part II" (PDF). QST. American Radio Relay League (February 1967): 30–36. OCLC 1623841. Retrieved 22 December 2018.

- "Bureau of Standards to Test Seven Standard Wavelengths" by Carl H. Butman, Radio World, February 24, 1923, page 13.

- "Radio Signals of Standard Frequency", Radio Service Bulletin, June 1, 1923, page 22.

- Fey, Lowell. "New Signals from an Old Timer...WWV" (PDF). Broadcast Engineering (July 1971): 44–46. ISSN 0007-1994. Retrieved 2018-12-23.

- "WWV to be Relocated" (PDF). NBS Technical News Bulletin: 215, 218. December 1965. Retrieved 2018-12-23. Also contains details about the construction of the WWV transmitters.

- "WWV's 25 MHz Signal Back on the Air", April 7, 2014 (ARRL.org)

- DX Listening Digest 5-016 (January 26, 2005) edited by Glenn Hauser: "For a short time, a broadcaster from Atlanta named John Doyle's voice was used on the broadcast; the voice announcement was then re-recorded by a radio personality in the San Francisco area named Lee Rodgers ... NIST Radio Station WWVH in Kauai, Hawaii, has a similar broadcast using a female voice. The announcer, Jane Barbe, did pass away several years ago." — Glenn Nelson, NIST Radio Stations WWV/WWVB

- WWV: INSIDE TOUR! Fort Collins, Colorado on YouTube

- NIST (February 12, 2018). "Fundamental Measurement, Quantum Science and Measurement Dissemination". FY 2019: Presidential Budget Request Summary. Retrieved August 20, 2018.

[reduction of] $6.3 million supporting fundamental measurement dissemination, including the shutdown of NIST radio stations in Colorado and Hawaii.

- "FY 2019 NIST budget looks good for time stations". The SWLing Post. Retrieved 2019-02-24.

- "Science Notes: Death of a Sputnik Traced by New Radio System". The New York Times. January 19, 1958. pp. E11. Retrieved 2009-11-03.

- "Science: Slow Death". Time. January 27, 1958. Retrieved 2009-11-03.

- "NBS Miscellaneous Publication 236 (1967 edition): NBS Standard Frequency and Time Services" (PDF).

External links

- WWV Official Webpage (NIST.gov)

- Current WWV Geophysical alert text (NOAA.gov)

- "At The Tone: A Little History of NIST Radio Stations WWV & WWVH" (bandcamp.com)

- Achievement in Radio: Seventy Years of Radio Science, Technology, Standards and Measurement at the National Bureau of Standards by Wilbert F. Snyder and Charles L. Bragaw (1986)

- U.S. Patent 4582434 for WWV-controlled "time corrected, continuously updated clock" Applied for April 23, 1984 and issued April 15, 1986 to the Heath Corporation (USPTO.gov)

- U.S. Patent 4768178 for WWV-controlled "high precision radio signal controlled continuously updated digital clock" Applied for February 24, 1987 and issued August 30, 1988 to Precision Standard Time, Inc. (USPTO.gov)

- A Precision Radio Clock for WWV Transmissions by David L. Mills, University of Delaware Electrical Engineering Department, 1997. Describes WWV time code decoding software using Digital Signal Processing (udel.edu)

- "Class project: a WWV/H receiver demodulator/decoder" Lecture slides for WWV time decoder DSP algorithms by David L. Mills, University of Delaware, November 12, 2004 (udel.edu)

- "Receiving, identifying and decoding LF/HF radio time signals" by Nick Hacko, VK2DX (genesisradio.com.au)

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to WWV. |