Visiting card

A visiting card, also known as a calling card, is a small card used for social purposes. Before the 18th century, visitors making social calls left handwritten notes at the home of friends who were not at home. By the 1760s, the upper classes in France and Italy were leaving printed visiting cards decorated with images on one side and a blank space for hand-writing a note on the other. The style quickly spread across Europe and to the United States. As printing technology improved, elaborate color designs became increasingly popular. However, by the late 1800s, simpler styles became more common.[1]

By the 19th century, men and women needed personalized calling or visiting cards to maintain their social status or to move up in society. These small cards, about the size of a modern-day business card, usually featured the name of the owner, and sometimes an address. Calling cards were left at homes, sent to individuals, or exchanged in person for various social purposes. Knowing and following calling card “rules” signaled one’s status and intentions.[2]

History

Visiting cards became an indispensable tool of etiquette, with sophisticated rules governing their use. The essential convention was that a first person would not expect to see a second person in the second's own home (unless invited or introduced) without the first having first left his visiting card at the second's home. Upon leaving the card, the first would not expect to be admitted initially, but instead might receive a card at his own home in response from the second. This would serve as a signal that a personal visit and meeting at home would be welcome. On the other hand, if no card was forthcoming, or if a card was sent in an envelope, a personal visit was thereby discouraged.

As an adoption from France, they were called une carte d'adresse from 1615 to 1800, and then became carte de visite or visiteur with the advent of photography in the mid 19th century. Visiting cards became common among the aristocracy of Europe, and also in the United States. The whole procedure depended upon there being servants to open the door and receive the cards and it was, therefore, confined to the social classes which employed servants.

If a card was left with a turned corner it indicated that the card had been left in person rather than by a servant.

Next day Paul found Stubbs' card on his table, the corner turned up. Paul went to Hertford to call on Stubbs, but found him out. He left his card, the corner turned up.

Some visiting cards included refined engraved ornaments, embossed lettering, and fantastic coats of arms. However, the standard form visiting card in the 19th century in the United Kingdom was a plain card with nothing more than the bearer's name on it. Sometimes the name of a gentlemen's club might be added, but addresses were not otherwise included. Visiting cards were kept in highly decorated card cases.

The visiting card is no longer the universal feature of upper middle class and upper class life that it once was in Europe and North America. Much more common is the business card, in which contact details, including address and telephone number, are essential. This has led to the inclusion of such details even on modern domestic visiting cards: Debrett's New Etiquette in 2007 endorsed the inclusion of private and club addresses (at the bottom left and right respectively) but states the inclusion of a telephone or fax number would be "a solecism".[3]

According to Debrett's Handbook in 2016, a gentleman's card would traditionally give his title, rank, private or service address (bottom left) and club (bottom right) in addition to his name. Titles of peers are given with no prefix (e.g. simply "Duke of Wellington"), courtesy titles are similarly given as "Lord John Smith", etc., but "Hon" (for "the Honourable") are not used (Mr, Ms, etc. being used instead). Those without titles of nobility or courtesy titles may use ecclesiastical titles, military ranks, "Professor" or "Dr", or Mr, Ms, etc. For archbishops, bishops, deans and archdeacons, the territorial title is used (e.g. "The Bishop of London"). Men may use their forenames or initials, while a married or widowed woman may either use her husband's name (the traditional usage) or her own. The only post-nominal letters used are those indicating membership of the armed forces (e.g. "Captain J. Smith, RN"). The Social Card, which is a modern version of the visiting card, features a person's name, mobile phone number, and email address, with an optional residential address rarely included; family social cards include the names of parents and children.[4]

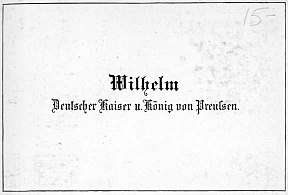

Visiting card of Kaiser Wilhelm

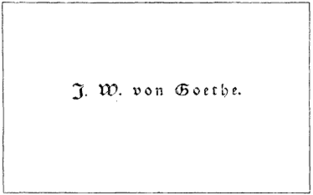

Visiting card of Kaiser Wilhelm Visiting card of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe

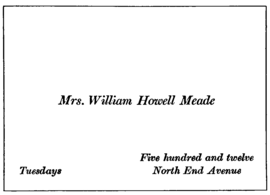

Visiting card of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe Sample lady's visiting card, specifying an "At Home" day

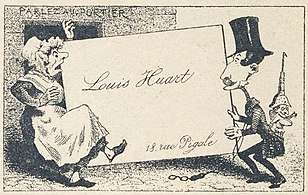

Sample lady's visiting card, specifying an "At Home" day Visiting card of Louis Adrien Huart, caricaturist for Le Charivari

Visiting card of Louis Adrien Huart, caricaturist for Le Charivari Visiting card of Antonín Langweil

Visiting card of Antonín Langweil- Visiting card case

Victorian silver visiting card case

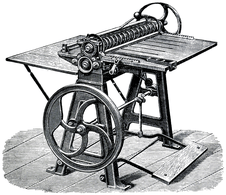

Victorian silver visiting card case A Oscar Friedheim card cutting and scoring machine from 1889, capable of producing 100,000 visiting cards a day

A Oscar Friedheim card cutting and scoring machine from 1889, capable of producing 100,000 visiting cards a day

Common sizes

| Width | Height | Used in |

|---|---|---|

| 76 mm | 38 mm | United Kingdom (gentleman's visiting card) (3 × 1 1⁄2 in)[4] |

| 83 mm | 57 mm | United Kingdom (traditional lady's, joint or family visiting card) (3 1⁄4 × 2 1⁄4 in)[4] |

| 85 mm | 48 mm | Iran |

| 85 mm | 55 mm | Germany, Italy, France, Spain, Switzerland, Netherlands, Austria, Turkey |

| 88.9 mm | 50.8 mm | United States, Canada and Pakistan(3 1⁄2 × 2 in) |

| 89 mm | 64 mm | United Kingdom (alternative lady's, joint or family visiting card, and modern social card) (3 1⁄2 × 2 1⁄2 in)[4] |

| 90 mm | 55 mm | Australia, India, Sweden, Norway, Denmark |

| 90 mm | 54 mm | Hong Kong |

| 90 mm | 50 mm | Argentina, Czech Republic, Finland, Russia, Hungary, Poland, Romania, Sri Lanka |

| 91 mm | 55 mm | Japan |

| Width | Height | Format |

|---|---|---|

| 74 mm | 52 mm | DIN A8 |

| 81 mm | 57 mm | DIN C8 |

| 85 mm | 55 mm | check card (EU) |

| 85.6 mm 100 mm | 54 mm 65 mm | check card (ISO 7810) check card with photo |

See also

- Business card

- Electronic business cards

- Carte de visite, a related but usually distinct item

- Compliments slip

References

- Mayor, A. Hyatt (1943). "Old Calling Cards". The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin. 2 (2): 93–98. doi:10.2307/3257136. JSTOR 3257136.

- Resor, Cynthia (March 4, 2019). "What has replaced 19th Century Parlors and Calling Cards?". https://teachingwiththemes.com/. External link in

|website=(help) - Morgan, John (2007). Debrett's New Guide to Etiquette & Modern Manners: The Indispensable Handbook. Macmillan. p. 168. ISBN 978-1429978286.

- Elizabeth Wyse (19 April 2016). Debrett's Handbook. Debrett's. pp. 418–420. ISBN 9780992934866.

- Ray Trygstad. "Calling Cards", Rays of Light July 21, 2003

- United States Army. "Army Regulation 600–25 Salutes, Honors, and Visits of Courtesy" Washington, D.C.: Headquarters, Department of the Army, 24 September 2004.

- Emily Post. "Cards and Visits", Chapter 10 of Etiquette in Society, in Business, in Politics and at Home. New York: Funk & Wagnalls Company, 1922. ISBN 1-58734-039-9.

- Robert Chambers, editor. "Visiting Cards of the 18th Century", Chapter 5 June of the Book of Days. London: W. & R. Chambers, 1869.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Visiting cards. |