Pizzle

Pizzle is an old English word for penis, derived from Low German pesel or Flemish Dutch pezel, diminutive of pees, meaning 'sinew'.[1] The word is used today to signify the penis of an animal,[2] chiefly in Australia and New Zealand.[3]

Original uses

It is also known, at least since 1523, especially in the combination "bull pizzle", to denote a flogging instrument made from a bull's penis. It derives from the Low German pesel or Flemish pezel, originally from the Dutch language pees meaning "sinew".[4]

In William Shakespeare's play, Henry IV, Part 1, the character Falstaff uses the term as an insult (Act 2, Scene IV):[5]

'Sblood, you starveling, you elf-skin, you dried neat's tongue, you bull's pizzle, you stock-fish!

In heraldry

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Vilené in heraldry. |

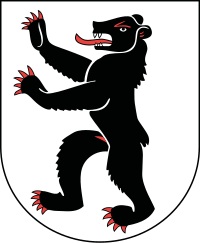

In heraldry, the term pizzled (or vilené in French blazon)[6] indicates the depiction or inclusion of an animate charge's genitalia, especially if colored (or "tinctured") differently.[7]

The bear in the coat of arms of Appenzell is represented pizzled, and omission of this feature was seen as a grave insult. In 1579, the pizzle was forgotten by the printer of a calendar printed in Saint Gallen, which brought Appenzell to the brink of war with Saint Gallen.[8][9][10]

Prior to 2007, the lion on the coat of arms of the Nordic Battlegroup featured a pizzle, but in 2007 the commander ruled that the lion's penis had to be removed. Since civilian women are often sexually abused in the war zones of the world, they did not consider the depiction of a penis appropriate on a uniform worn into battle. However, this decision has been questioned by some Swedish heraldists, including heraldic artist Vladimir Sagerlund, who has asserted that coats of arms containing lions without a penis were historically given to those who had betrayed the Swedish Crown.[11]

Modern uses

Paramilitary use in World War II

Pizzles were widely used as late as 1944 by local paramilitary units on the Eastern Front, usually as a disciplinary measure against arrested or bullied civilians.[12]

Animal consumption

Pizzles, or bully sticks, are mostly produced today as chewing treats for dogs.[2]

Human consumption

In addition to being used as a dog treat, pizzles are also eaten by humans for their purported health benefits (according to traditional Chinese medicine) such as being low in cholesterol and high in protein, hormones, and vitamins, and minerals such as calcium and magnesium,[2] although little empirical evidence supports these claims. Pizzles for human consumption are prepared either by freezing or by drying.

Scottish deer pizzles are thought to boost stamina and were used by Chinese athletes at the 2008 Summer Olympics.[2][14] Pizzles can be served in soup, and if they have been dried they can be turned into a paste. Pizzles may also be mixed with alcoholic beverages or simply thawed (if frozen) and eaten.[2] In Jamaica, bull pizzles are referred to as "cow cods" and are eaten as cow cod soup. Like many pizzle-based foods, cow cod soup is claimed to be a male aphrodisiac.

References

- "Online Etymology Dictionary". Retrieved 2009-03-30.

- "Beijing Olympics 2008 in short". The Daily Telegraph. 21 Aug 2008. Retrieved 2009-03-31.

- "pizzle". OED.

- Harper, Douglas. "pizzle (n.)". www.etymonline.com. Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 27 November 2017.

- "The First part of King Henry the Fourth - SCENE IV. The Boar's-Head Tavern, Eastcheap". shakespeare.mit.edu. Retrieved 27 November 2017.

- Rietstap, J. B. (1884). "Armorial général; précédé d'un Dictionnaire des termes du blason". G. B. van Goor zonen: XXXI.

Vilené: se dit un animal qui a la marque du sexe d'un autre émail que le corps

Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - http://www.heraldica.org/topics/sex.htm (accessed July 13, 2016).

- Neubecker, Ottfried (1976). Heraldry : sources, symbols, and meaning. New York: McGraw-Hill. p. 120. ISBN 9780070463080.

- Strehler, Hermann (1965). "Das Churer Missale von 1589". Gutenberg-Jahrbuch. 40: 186.

- Grzimek, Bernhard (1972). Grzimek's Animal life encyclopedia. 12. New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold Co. p. 119.

- "Heraldists want penis reinstated on military badge". The Local.se. Retrieved 2015-11-07.

- Ernő Szép, The Smell of Humans: A Memoir of the Holocaust in Hungary, translated by John Bátki (Budapest: Corvina and Central European University Press, 1994)

- Food for the Armed Forces. 5–6. Quartermaster Food and Container Institute for the Armed Forces. 1946.

- "G20 summit represents a good start". The Scotsman. 15 November 2008. Retrieved 2009-03-31.