Uroscopy

Uroscopy is the historical medical practice of visually examining a patient's urine for pus, blood, or other symptoms of disease.

The first records of uroscopy as a method for determining symptoms of an illness date back to the 4th millennium BC, and became common practice in Classical Greece. Later reaching medical predominance during the Byzantine Era & High Middle Ages, the practice eventually was replaced with more accurate methods during the early modern period, with uroscopy being considered inadequate due to the lack of empirical evidence and higher standards of post-Renaissance medicine.

In modern medicine, visual examination of a patient's urine may provide preliminary evidence for a diagnosis, but is generally limited to conditions that specifically affect the urinary system such as urinary tract infections, kidney and bladder issues, and liver failure.

It is notable that pregnancy and diabetes are two diagnoses that uroscopy, although out of favor with medical professionals, has a good rate of predicting.

History

Records of urinalysis for uroscopy date back as far as 4000 BC, originating with Babylonian and Sumerian physicians.[1] At the outset of the 4th century BC Greek physician Hippocrates hypothesized that urine was a "filtrate" of the four humors, and limited possible the diagnoses resulting from this method to issues dealing with the bladder, kidneys, and urethra.[2] This in turn led another Greek physician, Galen, to refine the idea down to urine being a filtrate of only blood, and not of black bile, yellow bile, or phlegm.

Byzantine medicine followed, though it maintained its roots from Greco-Roman antiquity, and continued the application and study of uroscopy — it eventually becoming the primary form of ailment diagnosis. Byzantine physicians created some of the foundational codifications of uroscopy, with the most well known example being a 7th-century guide on uroscopic methods: Theophilus Protospatharius's On Urines. The work, along with others, became widely popular and accelerated the rate at which uroscopy spread throughout the Mediterranean. Over time these Byzantine works inspired further interpretation by other prominent culture's scholars (like the Arab Jewish Isaac Israeli ben Solomon and his urine-hue classification chart), though greater propagation led to a widened application of uroscopy and eventually uroscopic diagnoses of non-urinary related diseases and infections became standard.[3]

Pivotal in the spread of uroscopy, Constantine the African's Latin translations of Byzantine and Arab texts inspired a new era in uroscopic interest specifically in western Europe throughout the High Middle Ages.[4] Despite this popularization, uroscopy was still mostly maintained by the principals Hippocrates's and Galen's first postulated, aided by Byzantine interpretations that were further disseminated during this period in works by French physicians of the era Bernard de Gordon and Gilles de Corbeil.[4]

The practice was upheld as the standard until the beginning of the 16th century, when influence from cultural movements like the Renaissance inspired the re-examination of its methods, both to re-evaluate its effectiveness and explore new applications. During this period, a lack of empirical evidence supporting uroscopy and the introduction of new medical practices developed using the scientific method contributed to its gradual decline among licensed physicians. Early modern doctors, like the Swiss medical pioneer Paracelsus, began researching more empirically qualified approaches to diagnosis and treatment — an integral part of the Medical Renaissance and its redefining how we look at medicine —which only further hastened the decline of uroscopy.[4] Since the beginning of the 17th century the practice has been largely considered unverifiable and unorthodox, and became a subject of satire (including multiple satirical references in the plays of Shakespeare). It was still practiced by "unlicensed practitioners" by popular demand up until around the beginning of the 19th century.[1]

Though uroscopy is no longer popular in modern medicine, examples of its preliminary diagnostic utility still exist in simplified and empirically proven forms.[5]

Incidentally, as the decline of uroscopy continued a new form of divination emerged from its remnants in "Uromancy" — the analysis of one's urine for fortune-telling or state-reading purposes. Although uromancy initially gained interest in the 18th and 19th centuries, it is rarely practiced and unknown to most in the present era.

Procedures and conventions

Practitioners of uroscopy are referred to as uroscopists. In the era in which uroscopy was a popular way of thinking, one of the major benefits was the lack of surgical operations, lending itself to the most conservative of adherents to the Hippocratic Oath.

Matula (flask)

A uroscopy flask, also known as a "matula", is a piece of transparent glass — this is imperative as colorations, along with any deformations, in the glass may lead to a missdiagnosis — that is circular at the bottom, while there is a thin neck at the top, and an opening for the patient to urinate in.

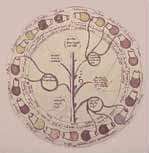

Urine wheel

The uroscopy wheel is a diagram that linked the color of urine to a particular disease. It usually has twenty different uroscopy flasks with urine of different colors aligned around the border of the circle. Each flask has a line that connects it to a summary of a particular disease. This allowed doctors to have a quick reference guide to twenty different types of urine.[6]

Temperature

The temperature at which the urine is examined is a very important factor to consider in the process of uroscopy. When a patient urinates, the urine will be warm, so it is necessary for it to stay warm for proper evaluation. The external temperature should be the same as the internal temperature. When the temperature of urine goes down the bubbles in it will change. Some of them will disappear, but some will remain. With the temperature decrease particles and impurities will be more difficult to evaluate. They will move toward the middle of the flask, then sink to the bottom. They will all mix, making it more difficult to see the impurities.

Another problem with urine cooling is that it would become thicker. The longer that it had to cool down the more likely it was that the crystals in the it would bond together, causing it to thicken. This could lead to a false diagnosis, that is why doctors usually inspected the urine quickly.

Richard Bright in the 19th century A.D. invented a technique that allowed doctors to examine a patients urine effectively after the temperature had dropped. The process involved heating water, then inserting the uroscopy flask containing cooled urine. This would heat the urine causing the crystals that formed during loss of temperature to break down. As a result, the urine will become thin again. This process is very effective, but a doctor should “also be careful not to shake them much before you inspect them for you will move the particles and destroy the bubbles and dilute the deposits and confuse the situation,” (The Late Greco-Roman and Byzantine Contribution to the Evolution of Laboratory Examinations of Bodily Excrement. Part1: Urine, Sperm, Menses and Stools, Pavlos C. Goudas).

Lighting

Since identifying the color of the urine is essential for a proper diagnosis, the lighting is crucial. This is a very complicated step in the uroscopy test. The doctor must not visually examine the urine in an overly lit location, because it will make the urine seem too bright. He can not examine the urine in a poorly lit location, because he will not be able to properly see the urine. So, he must examine the urine in both conditions. This is done to offset the effects of not enough light and too much light. After he examines in both conditions the doctor must use his best judgment, to make a diagnosis.

Common diseases identified by uroscopic methods

Diabetes

In 1674 English doctor Thomas Willis submitted into medical literature a peculiar (and peculiarly found) relationship he'd observed: people with type 1 diabetes usually have sweet tasting urine — this is due to an oversaturation of glucose in the blood, the excess of which is excreted out via urine, as the diabetic lacks sufficient insulin to process the high amounts of glucose.

Jaundice

Yellowish discoloration of the whites of the eyes, skin, and mucous membranes caused by deposition of bilirubin in these tissues. It occurs as a symptom of various diseases, such as hepatitis, that affect the processing of bile. Also called Icterus.

Doctors would test by using their vision. If the urine had a brownish tint then the patient would most likely have jaundice.

Kidney disease

The kidneys are supposed to filter excesses (especially urea) from the blood and excrete them, along with water, as urine. When they are not performing this task the patient is suffering from kidney disease. The medical field that studies the kidneys and diseases affecting the kidney is called nephrology, from the Ancient Greek name for kidney.

Doctors would test urine using a visual examination. If the urine was red and/or foamy the patient was suffering from kidney disease.

See also

References

- Connor, Henry (2001-11-01). "Medieval uroscopy and its representation on misericords – Part 1: uroscopy". Clinical Medicine. 1 (6): 507–509. doi:10.7861/clinmedicine.1-6-507. ISSN 1470-2118. PMC 4953881. PMID 11792095.

- "Urinalysis in Western culture: A brief history". Kidney International. 71 (5): 384–387. March 2007. doi:10.1038/sj.ki.5002057.

- "Doctor's Review | Liquid Gold". www.doctorsreview.com. Retrieved 2019-03-29.

- Eknoyan, Garabed (2007-06-01). "Looking at the Urine: The Renaissance of an Unbroken Tradition". American Journal of Kidney Diseases. 49 (6): 865–872. doi:10.1053/j.ajkd.2007.04.003. ISSN 0272-6386.

- "Urine color - Symptoms and causes". Mayo Clinic. Retrieved 2019-03-29.

- ḎḤWTY. "The Urine Wheel and Uroscopy: What Your Wee Could Tell a Medieval Doctor". Ancient Origins. Retrieved 30 March 2018.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Uroscopy. |

- Buckland, Raymond (2003). The fortune-telling book: the encyclopedia of divination and soothsaying. Visible Ink Press. p. 493. ISBN 1-57859-147-3.