Upsilon Sigma Phi

The Upsilon Sigma Phi (ΥΣΦ) is the oldest Greek-letter organization and fraternity in Asia.[1][2] It is the oldest student male-exclusive organization in the University of the Philippines that has been in continuous existence since its founding. It is also an exclusive fraternity where membership is by invitation only. The Upsilon Sigma Phi has two chapters, a combined UP Diliman/UP Manila chapter and a second one in UP Los Banos.[3]

| Upsilon Sigma Phi | |

|---|---|

| ΥΣΦ | |

| |

| Founded | 1918 University of the Philippines Diliman, Quezon City |

| Type | University |

| Motto | We gather light to scatter |

| Colors | Cardinal Red Old Blue |

| Symbol | Fraternity seal |

| Flower | Pink Rose |

| Chapters | 2 (U.P. Diliman/U.P. Manila and U.P. Los Baños) |

| Members | 3,500+ total lifetime |

| Headquarters | University of the Philippines |

| Website | http://www.upsilon.com |

Its vast network of influential alumni both in public service and private enterprise has led several publishers to cite it as the most prominent and influential fraternity in the Philippines.[4][5][6]

History

Upsilon Sigma Phi was founded in 1918 by twelve students and two professors from the University of the Philippines. It was formally organized on November 19, 1920 in a meeting held at the Metropolitan Restaurant in Intramuros, Manila, where the fraternity elected its first officers (among which include Agapito del Rosario, one of the founders of the Socialist Party of the Philippines and later on Mayor of Angeles, Pampanga).[7][8]

Four months later, on March 24, 1921, the Greek letters "ΥΣΦ" standing for the initials of the name "University Students Fraternity" were formally adopted. It also formally adopted its themes, rites, and motto ("We gather light to scatter"), all influenced by freemasonry. Its first honorary fellow, University Regent Conrado Benitez, wrote the Upsilon Hymn which later would be sung before and after every formal meeting.[9]

Early years (1920-1940s)

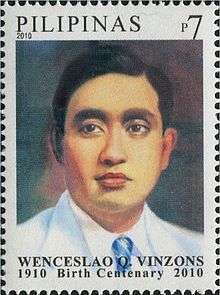

The fraternity's early years set its tradition of exclusivity. Invitations for membership were extended only to individuals who served in leadership positions, possessed leadership potential, or excelled in their respective fields.[7] On campus, thirteen of its members chaired the UP Student Council from 1930-1949 (including Wenceslao Vinzons, Jose Laurel Jr., and Sotero Laurel). Its members were also prominent contributors in campus publications, a number of whom served as Editor-in-Chief of the Philippine Collegian (such as Arturo Tolentino and Armando Malay) and the now defunct annual publication, The Philippinensian.[10]

During this time, then UP Student Council President Wenceslao Vinzons earned himself the title "Father of Student Activism" when he, together with members of the fraternity, led demonstrations before the Philippine Congress to protest the insertion of a provision in the appropriations act that gave lawmakers a salary increase.[11]

World War Two (1942-1945)

Members of the fraternity also took key roles during World War II. Among those were Wenceslao Q. Vinzons (who led guerilla forces in Camarines), Agapito del Rosario, and José Abad Santos (Acting President of the Philippines, Secretary of Justice, and Chief Justice of the Supreme Court), all of whom were executed for refusing to swear allegiance to the Japanese.

Jose P. Laurel served as "puppet president" under the Japanese occupation, who tried to protect the interests of the Filipino people through bureaucratic resistance while suffering rebuke from his critics who accused him of collaboration with the Japanese.[12]

Post-War (1946-1960s)

In 1947, the fraternity established a chapter in UP Los Banos.

During the 1950s, the fraternity hosted the Cavalcades, a series of stage plays and musicals that began on campus and eventually toured nationwide.[13] Profits from "Aloyan" and "Hanako" plays were used to help finance the construction and furnishing of the Church of the Holy Sacrifice in the Diliman campus.[7] These productions were led by writer Teddy Yabut and musicians Dick Zamora and Manuel Martell. One of the fraternity's productions, Linda, casted then 17-year-old Pilita Corrales.[7]

Through the efforts of the UP Alumni Association headed by Upsilonian Hermenegildo Reyes, the fraternity helped raise funds for the construction of the bell tower called the "Carillon" in 1952.[7] The tower still stands today as a landmark in the Diliman campus.

Under the term of Eric De Guia ("Kidlat Tahimik") as UP Student Council Chairman, the UP Student Union building was renamed Vinzons Hall in honor of Wenceslao Vinzons.

The Marcos Presidency (1965-1980s)

The administration of President Ferdinand E. Marcos saw Upsilon members lead opposing sides in the leadership of the Philippines. Fellows with the administration were President Ferdinand Marcos, Senate President Arturo M. Tolentino (who went on to become Philippine Vice President), Supreme Court Chief Justice Querube Makalintal (who after his retirement would be elected Speaker of the Batasang Pambansa), Secretary of Education and former UP President Onofre Corpuz, Batasan Speaker Nicanor Yniguez, Central Bank of the Philippines Governor Alfonso Calalang, and industry magnate Roberto Benedicto among many others.

Leading the opposition were senators Benigno S. Aquino, Jr., Gerardo Roxas, Salvador H. Laurel. Mamintal A.J. Tamano, and Domocao Alonto.[14] After the assassination of Aquino, Salvador Laurel would lead the opposition against the Marcos administration with Corazon Aquino and become Vice President after the 1986 EDSA Revolution.

Waging an ideological war were Upsilon members with the left Melito Glor[15] and Merardo Arce, who both served as commanders of the New People's Army. After their deaths, the New People's Army Southern Luzon and Mindanao Commands would, in their honor, be named the Melito Glor Command and the Merardo Arce Command, respectively.

In the arts, Behn Cervantes founded the UP Repertoiry Company to "combat the censorship that was in place during martial law."

Controversies

Initiation-related hazing

The death of Gonzalo Mariano Albert on July 18, 1954 due to initiation-related hazing involving Upsilon Sigma Phi is the first recorded hazing death in the Philippines.[16] Mariano was allegedly mauled by other fraternity members after failing to do an assigned task.[17]

President Ramon Magsaysay created the Castro Committee on October 1954 to investigate the death. The eponymous committee was headed by Executive Secretary Fred Ruiz Castro joined by UP faculty members Arturo Garcia and V. Lontok. They submitted a 116-page report to Magsaysay and found hazing to be the cause of Albert's death. They also recommended the expulsion of 4 officers of Upsilon, suspension of 25 members for one year, suspension of 19 neophytes for a semester, and reprimand of 3 other members. The report also called for reforms on university regulation on fraternities and sororities and the prohibition of all forms of physical initiation. The report was not acted upon.[18]

Fraternity wars

On November 14, 2018, members of Upsilon Sigma Phi and Alpha Phi Beta fraternities were involved in physical confrontations at Palma Hall in the UP Diliman campus. The next day, another incident, supposedly involving guns, occurred along Magsaysay Avenue inside the same university. An official statement released by the university administration however stated that what occurred was a "car chase" and not a "shooting incident" between the warring fraternities. “The incidents are being investigated and charges will be filed against those found to be criminally liable. The penalties for violence are severe, and can include expulsion from the university,” the statement added.[19][20]

Upsilon Sigma Phi leaks scandal

On November 20, 2018, an anonymous Twitter account, @100Upsilon, posted unconfirmed screenshots and archives purported to be from the group chat between members of Upsilon Sigma Phi. The conversations contained misogynistic, homophobic, racist, Islamophobic, pro-genocide, pro-violence, and pro-Martial Law content.[21] The disclosures attracted widespread attention, and garnered significant backlash. Numerous organizations and personalities across the country called for accountability and abolition of the culture of hegemonic masculinity within the fraternity's ranks.[22][23][24]

Membership

Membership to the Upsilon Sigma Phi is by-invitation and exclusive to male individuals in the University of the Philippines Diliman/Manila and Los Banos campuses. Selection is based on an individual's leadership position or potential and prominence in their respective fields (both on- and off-campus).[2]

Its alumni roster consists of a diverse roll of members in public service, industry, medicine, military, and academia among others.[2][25] In government alone, the fraternity has produced 3 Philippine Presidents, 2 Vice Presidents, 15 Senators, 15 Supreme Court Justices, 65 House Representatives, 19 Governors, 4 Solicitor Generals, 6 AFP Generals, 1 AFP Chief-of-Staff, and 1 BSP Governor notwithstanding numerous more that have led executive departments and agencies, judicial incumbencies, local government units, and other constitutional offices.[26][9][27][28] Beyond public service, its roster also includes a number of National Scientists, National Artists, and pioneers in research and medicine.[29][30][31]

Notable people known to be Upsilon Sigma Phi brothers include:

- Ferdinand Marcos – 10th Philippine President, Senate President, and Ilocos Norte Representative[32][33]

- José P. Laurel – 3rd Philippine President, Senator, and Supreme Court Justice[34]

- José Abad Santos – Acting President of the Philippines, Chief Justice of the Supreme Court[35]

- Arturo Tolentino – Philippine Vice President, 12th Senate President, Secretary of Foreign Affairs and Representative from Metro Manila[36]

- Salvador Laurel – Philippine Vice President, Prime Minister, Senator, and Secretary of Foreign Affairs[37][38]

- Joker Arroyo – Senator, Executive Secretary and Makati Representative[39]

- Richard Gordon – Senator and Tourism Secretary[40][41]

- Francis Pangilinan – Senate Majority Floor Leader[9][42]

- Benigno Aquino Jr. – Philippine Senator and Governor of Tarlac[37]

- Wenceslao Q. Vinzons – World War II war hero, provincial governor of Camarines Norte[43]

References

- "History of Philippine Fraternities". Retrieved 2018-08-09.

- http://upsilon.com

- https://www.uplbosa.org/upupsilon

- Nov 22, Paul John Caña |; 2018. "An Almost Complete List of Everyone Insulted in the #LonsiLeaks Scandal". Esquiremag.ph. Retrieved 2019-05-21.CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

- "PressReader.com - Your favorite newspapers and magazines". www.pressreader.com. Retrieved 2019-05-21.

- "EDITORIAL: All their might in tatters". Tinig ng Plaridel. 2018-11-22. Retrieved 2019-05-21.

- "Upsilon Sigma Phi - History". Upsilon Sigma Phi. Retrieved 2020-06-20.

- Sangil, Max (2015-08-26). "Sangil: Pampanga's Political Stars of Yesteryears (Part 2)". Sunstar. Retrieved 2020-06-20.

- Ninety Years of Upsilon Sigma Phi

- Evangelista, Oscar L. (2008). Icons and Institutions: Essays on the History of the University of the Philippines, 1952-2000. UP Press. ISBN 978-971-542-569-8.

- Dooc, Emmanuel (2019-09-27). "'Wenceslao Q. Vinzons: The Hero the Nation Forgot' | Emmanuel Dooc". BusinessMirror. Retrieved 2020-06-20.

- "Philippine History -- President Jose P Laurel". filipino.biz.ph. Retrieved 2019-04-20.

- Torrevillas, Domini M. "Dick Zamora and his music". philstar.com. Retrieved 2020-06-21.

- http://www.manilatimes.net/ninoy-aquino-hero-or-heel/213895/

- http://www.philippinerevolution.net/ndf/hnm/pages/melitoarticle.shtml

- "AnimatED: Kapatiran ng kamatayan" [AnimatED: Brotherhood of death]. Rappler (in Filipino). 2 October 2017. Retrieved 4 October 2017.

- "Casualties of frat-related violence in UP". GMA News. 5 September 2007. Retrieved 6 October 2017.

- Abinales, Patricio (12 July 2012). "A hazing". Rappler. Retrieved 4 October 2017.

- Mateo, Janvic (2018-11-16). "Warring UP fraternity members face expulsion". The Philippine Star. Retrieved 2018-11-27.

- Tomacruz, Sofia (2018-11-14). "U.P. says car chase, not shooting, occurred in Diliman campus". Rappler. Retrieved 2018-11-27.

- Madarang, Catalina Ricci S. (2018-11-22). "Upsilon Sigma Phi members denounce views of alleged frat brothers in #LonsiLeaks". Interaksyon. Retrieved 2018-11-23.

- "UP frat in hot water over discriminatory, misogynistic conversations". ABS-CBNnews.com. 2018-11-23. Retrieved 2018-11-23.

- Patag, Kristine Joy (2018-11-23). "People insulted in the controversial #LonsiLeaks speak out". The Philippine Star. Retrieved 2018-11-23.

- Madarang, Catalina Ricci S. (2018-11-22). "What concerned groups are saying about Upsilon Sigma Phi's #LonsiLeaks". Interaksyon. Archived from the original on 2018-11-22. Retrieved 2018-11-23.

- "Duterte recognizes UP frat, hails its 'dedication to nation-building'". October 11, 2018.

- "Upsilon Sigma Phi - iskWiki!". iskwiki.upd.edu.ph. 2009-02-22. Retrieved 2019-04-21.

- Silvestre, Jojo (November 19, 2018). "A legacy in nation-building".

- Matoto, Bing (October 24, 2018). "The gathered lights of the Upsilon Sigma Phi".

- Nemenzo, Gemma A. (2009). We gather light to scatter : ninety years of Upsilon Sigma Phi. Quezon City, Philippines. ISBN 9789719426509. OCLC 841185029.

- Avecilla, Victor (November 11, 2018). "Notes on the Upsilon centennial".

- "Blazing trails in arts and culture". November 19, 2018.

- Elefan, Ruben S. (1997-01-01). Fraternities, Sororities, Societies: Secrets Revealed. St. Pauls. p. 21. ISBN 9789715048477.

- Spence, Hartzell (1964). For Every Tear a Victory: The Story of Ferdinand E. Marcos. McGraw-Hill. p. 33.

- Company, Fookien Times Publishing (1986). The Fookien Times Philippines Yearbook. Fookien Times. p. 226. ISBN 9789710503506.

- Torrevillas, Domini (February 4, 2014). "'Arangkada 2014' sa Manila".

- "Toronto Upsilon Sigma Phi and Sigma Delta Phi to host 2006 reunion". April 1, 2005. Retrieved April 4, 2019.

- Avecilla, Victor (November 15, 2016). "Remembering Salvador 'Doy' Laurel". Retrieved April 6, 2019.

- "Remembering Doy Laurel". March 23, 2014.

- Torrevillas, Domini M. "Joker remembered". philstar.com. Retrieved 2017-09-02.

- "About Dick Gordon". Archived from the original on February 2, 2010. Retrieved 2010-02-09.

- Torrevillas, Domini M. "Shaping leaders, inspiring change". philstar.com. Retrieved 2017-09-02.

- Porcalla, Delon (January 30, 2012). "Law frats also in spotlight at CJ trial".

- Filipinos in History. National Historical Institute. 1989. p. 266. ISBN 9789715380034.