United States Fish Commission

The United States Fish Commission,[1] formally known as the United States Commission of Fish and Fisheries, was an agency of the United States government created in 1871 to investigate, promote, and preserve the fisheries of the United States. In 1903, it was reorganized as the United States Bureau of Fisheries, which operated until 1940. In 1940, the Bureau of Fisheries became part of the newly created Fish and Wildlife Service, under the United States Department of the Interior.

| United States Commission of Fish and Fisheries (1871-1903) United States Bureau of Fisheries (1903-1940) | |

Flag of the United States Bureau of Fisheries | |

| Agency overview | |

|---|---|

| Formed | 9 February 1871 |

| Preceding agency |

|

| Dissolved | 30 June 1940 |

| Superseding agency | |

| Jurisdiction | United States federal government |

| Parent agency | none (1871-1903) U.S. Department of Commerce and Labor (1903-1913) U.S. Department of Commerce (1913-1939) U.S. Department of the Interior (1939-1940) |

Organizational history

1871–1940

Robert Barnwell Roosevelt, a Democratic congressmen from New York's 4th Congressional District, originated the bill to create the U.S. Fish Commission in the United States House of Representatives. It was established by a joint resolution (16 Stat. 593) of the United States Congress on February 9, 1871,[2] as an independent commission with a mandate to investigate the causes for the decrease of commercial fish and other aquatic animals in the coastal and inland waters of the United States, to recommend remedies to the U.S. Congress and the states, and to oversee restoration efforts. The Commission was organized into three divisions: the Division of Inquiry respecting Food-Fishes and Fishing Grounds, the Division of Fisheries, and the Division of Fish-Culture.[3] The Commission was led first by Spencer F. Baird,[1] then Marshall McDonald, George Brown Goode, and finally George Bowers.

By an Act of Congress of February 14, 1903, the U.S. Fish Commission became part of the newly created United States Department of Commerce and Labor and was reorganized as the United States Bureau of Fisheries, with both the transfer and the name change effective on July 1, 1903.[4] In 1913, the Department of Commerce and Labor was divided into the United States Department of Commerce and the United States Department of Labor, and the Bureau of Fisheries became part of the new Department of Commerce.[5] In 1939, the Bureau of Fisheries was transferred to the United States Department of the Interior,[6] and on June 30, 1940, it was merged with the Interior Department's Division of Biological Survey to form the new Fish and Wildlife Service, an element of the Interior Department.[7]

Successor organizations

In 1956, the Fish and Wildlife Service was reorganized as the United States Fish and Wildlife Service and divided its operations into two bureaus, the Bureau of Sport Fisheries and Wildlife and the Bureau of Commercial Fisheries, with the latter inheriting the history and heritage of the old U.S. Fish Commission and U.S. Bureau of Fisheries.[8] Upon the formation of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) within the Department of Commerce on October 3, 1970, the Bureau of Commercial Fisheries merged with the saltwater laboratories of the Bureau of Sport Fisheries and Wildlife to form today's National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS), an element of NOAA,[9] and the former Bureau of Commercial Fisheries' research ships were resubordinated to the NMFS. During the 1972 and 1973, these ships were integrated with those of other parts of NOAA to form the unified NOAA fleet. The NMFS is considered the modern-day successor to the U.S. Fish Commission and U.S. Bureau of Fisheries, and the NOAA fleet of today also traces its history in part to them.

Commissioner of Fisheries

The Commissioner of Fisheries oversaw the U.S. Fish Commission (1871–1903) and the U.S. Bureau of Fisheries (1903–1940). The following served as Commmissioner of Fisheries:

1. Spencer Fullerton Baird (1871–1887)

2. G. Brown Goode (1887-1888)

3. Marshall McDonald (1888-1895)

– Herbert A. Gill (acting, 1895–1896)

4. John J. Brice (1896–1898)

5. George M. Bowers (1898–1913)

6. Hugh M. Smith (1913–1922)

7. Henry O'Malley (1922–1933)

8. Frank T. Bell (1933–1939)

– Charles T. Jackson (acting, 1939–1940)

Source[10]

Work

Research and publications

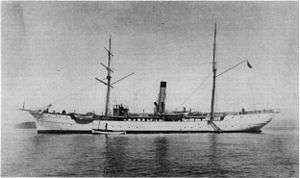

The U.S. Fish Commission carried out extensive investigations of the fishes, shellfish, marine mammals, and other life in the rivers, lakes, and marine waters of the United States and its territories; corresponded widely with marine researchers around the world; scrutinized fishing technologies; designed, built, and operated hatcheries for a wide variety of finfish and shellfish; and oversaw the fur seal "fishery" in the Territory of Alaska, including the Aleutian Islands. The Commission's research stations and surveys collected significant data on U.S. fish and fishing grounds, with considerable material going to the Smithsonian Institution.[1] Four ships were built for the Commission, including the 157-foot-long (47.9 m) schooner-rigged steamer USFC Fish Hawk, which served as a floating fish hatchery and fisheries research ship from 1880 to 1926; the 234-foot-long (71.3 m) brigantine-rigged steamer USFC Albatross, which operated as a fisheries research ship from 1882 to 1921 except for brief periods of United States Navy service in 1898 and from 1917 to 1919;[11] and the 90-foot-long (27.4 m) sailing schooner USFC Grampus, which was commissioned in 1886 and operated as a fisheries research ship until 1917. The Edenton Station hatchery was established in 1899.[12]

From 1871 to 1903, the Commission's Annual Report to Congress detailed its efforts and findings in all of these areas.[13] From 1881 to 1903, the Commission also published an annual Bulletin of the United States Fish Commission summarizing the commission's Annual Report to Congress and correspondence;[14] the bulletins included detailed catch reports from fishermen and commercial fishing port agents around the United States and Canada, reports and letters from naturalists and fish researchers around the United States and in other countries, and descriptions of the Commission's exploratory cruises and fish hatchery efforts. Beginning in 1884, the Commission published the seminal work The Fisheries and Fisheries Industries of the United States.[15]

Fishery enforcement

After the United States purchased Russian America from the Russian Empire in 1867 and created the Territory of Alaska, enforcement of whatever regulations to protect fisheries and marine mammals that existed in Alaska fell to the revenue cutters of the United States Revenue-Marine, which in 1894 became the United States Revenue Cutter Service and was one of the ancestor organizations of the United States Coast Guard.[16] On 14 June 1906, however, the United States Congress passed the Alien Fisheries Act to protect and regulate fisheries in the Alaska Territory by placing restrictions on the use of fishing tackle and on cannery operations in the territory and authorizing the U.S. Bureau of Fisheries to enforce the regulations.[16] The Bureau established regional districts throughout Alaska to organize fishery and marine mammal protection patrols but had no vessels suitable for fishery patrols in Alaska, and during the next few years relied on vessels borrowed from other United States Government agencies (such as the Revenue Cutter Service), on chartered vessels, and on transportation that canneries offered for free to Bureau of Fisheries agents.[16] This approach was not satisfactory for various reasons, such as the requirement for vessels of other government agencies to perform non-fishery-related functions, ethical concerns over accepting transportation from the canneries the Bureau of Fisheries agents were supposed to regulate, and the difficulty of enforcing regulations when the local fishing and canning industry personnel warned one another of the approach of Bureau of Fisheries agents who had accepted transportation on cannery vessels.[16] Each year after the 1906 passage of the Alien Fisheries Act, the Bureau of Fisheries requested more personnel and vessels with which to fulfill its regulatory and law enforcement responsibilities.[16] By 1911, when the Alaska fishing industry reached an annual value of nearly US$17 million,[17] it had become clear that the United States Government needed to make radical changes in how it enforced the provisions of the Alien Fisheries Act, including funding the acquisition of a fleet of dedicated fishery patrol vessels under the Bureau of Fisheries.[16]

In 1912, the Bureau purchased the former cannery tender SS Wigwam to serve as its first fishery patrol vessel; renamed USFS Osprey[16][17] – beginning a custom of naming the boats after birds common in Alaska[16] – she was commissioned in 1913[17] and quickly added the protection of fur seal and sea otter populations to her responsibilities.[17] The Bureau's first two purpose-built patrol vessels, USFS Auklet and USFS Murre joined her in 1917.[18] The Alaska enforcement fleet increased further in 1919 with four former United States Navy patrol vessels (USFS Kittiwake, USFS Merganser, USFS Petrel, and USFS Widgeon) transferred to the Bureau's Alaska fleet,[19][20][21] and in 1925 the Bureau established a district headquarters at the Naknek River for the Bristol Bay district and began to acquire a flotilla of motor launches to operate on the rivers, steams, and lakes in that area.[16] The Bureau also chartered vessels to support Alaska fisheries protection,[16] and Bureau patrol boats regularly protected migrating fur seal herds along the coast of Washington and Alaska.[16] On 25 October 1928, several Bureau of Fisheries vessels were tasked to join U.S. Navy vessels in enforcing the provisions of the Northern Pacific Halibut Act of 1924 in the Bering Sea and North Pacific Ocean, with their crews granted all powers of search and seizure in accordance with the act to protect populations of Pacific halibut.[16] By 1930 the Bureau had nearly 20 boats patrolling in Alaskan waters.[16] In 1933, it began to add speedboats to its Alaskan patrol inventory.[16]

In 1918, the Bureau of Fisheries augmented its fishery enforcement effort with a force of "steam watchmen," temporary employees who worked two to five months a year and kept a particular area under continuous observation; they also occasionally maintained lights and protected free-floating fish traps from drift.[22] The stream watchmen sometimes provided their own motorboats.[22] From an initial force of 10 men in 1918, the stream watchman force – which operated in both Southeast and Southcentral Alaska – grew to 59 men in 1922 and 220 in 1931.[22] In addition to stream watchmen, the Bureau also employed special wardens and operators of chartered boats to enforce fishery regulations.[22]

The Bureau of Fisheries also began to use aircraft for fishery patrols in 1929, chartering a seaplane from Alaska-Washington Airways to experiment with aerial patrol over Alaskan waters.[23] The aerial patrols were successful, and regular aerial patrols by Bureau of Fisheries agents using chartered aircraft began in 1930.[23] The patrols focused on Southeast Alaska,[23] and by 1939 logged an annual total of 6,859 miles (11,038 km) in 64 hours of flying.[23]

The fishery enforcement vessels and aircraft also provided transportation to Bureau of Fisheries personnel and assisted in the Bureau's scientific activities in Alaska.[16][23] In 1940, the Fish and Wildlife Service took over the fleet of patrol boats and the aerial patrol mission, and continued fishery enforcement operations, including the use of stream watchmen, wardens, and chartered boat operators, until Alaska became a state in 1959 and began to assume the responsibility for fishery protection in its waters.[16][23] By around 1960, the Fish and Wildlife Service had transferred many of its patrol boats to the State of Alaska and refocused its resources on its scientific mission.[16]

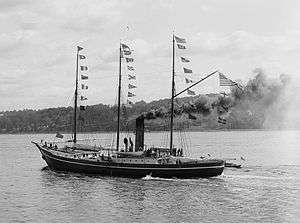

Pribilof tenders

On 21 April 1910, the United States Congress assigned the responsibility for the management and harvest of northern fur seals, foxes, and other fur-bearing animals in the Pribilof Islands in the Bering Sea, as well as for the care, education, and welfare of the Aleut communities in the islands, to the Bureau of Fisheries.[24] Initially the Bureau chartered commercial vessels to transport passengers and cargo to, from,and between the Pribilofs,[24] but by 1915 it had decided that a more cost-effective means of serving the islands would be to own and operate its own "Pribilof tender,"[24] a dedicated cargo liner responsible for transportation to, from, and between the islands.[24] Its first Pribilof tender, SS Roosevelt, operated from 1917 to 1919;[25] she was followed by MV Eider from 1919 to 1930,[26] and MV Penguin, which began operations in 1930.[27]

The operation of "Pribilof tenders" continued under the Bureau of Fisheries′ successor organizations, with the Fish and Wildlife Service employing MV Penguin on this service until 1950,[27] followed by MV Penguin II from 1950 to 1963,[28] MV Dennis Winn, which supplemented Penguin II′s service during the 1950s,[29] and MV Pribilof, which entered service in 1963 and continued to serve the Pribilofs after the creation of the NMFS in 1970.[30] The 58-year history of the "Pribilof tenders" did not come to a close until 1975, when the NMFS retired and sold Pribilof as part of a process of turning control of the local government and economy of the Pribilof Islands to their residents.[30]

Fleet

The U.S. Fish Commission operated five ships, and they used the prefix "USFC" while in commission. The Bureau of Fisheries inherited all five USFC ships, and its fleet expanded during the early 20th century. Its ships were given the prefix "USFS" while in commission, derived from an alternative name, "United States Fisheries Service," sometimes used for the Bureau. Although there were occasional exceptions (such as Grampus, Red Wing, and Roosevelt), the Fish Commission and Bureau of Fisheries custom was to name vessels after aquatic birds.

The later organizational history of the fleet paralleled that of the history of the Bureau's successor organizations. In 1940, the Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) took over the Bureau of Fisheries fleet, and when the FWS was reorganized as the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) in 1956, its seagoing ships were assigned to the USFWS's new Bureau of Commercial Fisheries (BCF), which inherited the history and heritage of the Fish Commission and Bureau of Fisheries. When the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) was created in 1970, its National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) was considered the successor to the BCF, and the NMFS took control of what had been the BCF's fleet. NMFS-controlled ships then were united with ships of other agencies to form a unified NOAA fleet during 1972–1973. The Fish Commission and Bureau of Fisheries fleets therefore are among the ancestors of today's NOAA fleet.

A partial list of the ships of the U.S. Fish Commission (USFC) and U.S. Bureau of Fisheries (BOF):

- USFC (later USFS) Albatros (research vessel with USFC 1882–April 1898 and August 1898 – 1903, then BOF 1903–1917 and 1919–1924)

- USFS Albatross II (research vessel, BOF 1926–1932)

- USFS Auklet (patrol vessel, BOF 1917–1940; then FWS 1940–1950)

- USFS Blue Wing (patrol vessel, BOF 1924–1940; then FWS 1940–1950s)

- USFS Brant (patrol vessel, BOF 1926–1940; then FWS 1940–1953)

- USFS Crane (patrol vessel, BOF 1928–1940; then FWS 1940–1960)

- USFS Curlew (fish culture vessel, BOF 1919–1937/1938)

- USFS Eider (Pribilof tender and patrol vessel, BOF 1919–1940; then FWS 1940–1942 and 1946–late 1940s)

- USFC (later USFS) Fish Hawk (research and hatchery vessel, USFC 1880–May 1898 and September 1898 – 1903, then BOF 1903–1918 and 1919–1926)

- USFS Fulmar (research vessel, BOF 1919–1933/1934)

- USFC (later USFS) Grampus (research and fish-culture vessel, USFC 1886–1903, then BOF 1903–1917)

- USFS Halcyon (research vessel, BOF 1919–1927)

- USFS Kittiwake (patrol vessel, BOF 1919–1940; then FWS 1940–late 1940s)

- USFS Merganser (patrol vessel, BOF 1919–1940; then FWS 1940–ca. 1942–1943)

- USFS Murre (patrol vessel, BOF 1917–1940; then FWS 1940–1942)

- USFS Osprey (patrol vessel, BOF 1913–1921)

- USFS Pelican (research and patrol vessel, BOF 1930–1940; then FWS/USFWS 1940–1958, NMFS ca. 1970/1971 to 1972)

- USFS Penguin (Pribilof tender, BOF 1930–1940; then FWS 1940–1950)

- USFS Petrel (patrol vessel, BOF 1919–1934)

- USFC (later USFS) Phalarope (research and fish-culture vessel, USFC 1900–1903, then BOF 1903–1932/1933)

- USFS Red Wing (patrol vessel, BOF 1928–1939)

- USFS Roosevelt (Pribilof tender, BOF 1915–1919)

- USFS Scoter (patrol vessel, BOF 1922–1940; then FWS 1940–1949)

- USFS Teal (patrol vessel, BOF 1928–1940; then FWS/USFWS 1940–1960)

- USFS Widgeon (patrol vessel, BOF 1919–1940; then FWS 1940–ca. 1944-1945)

Gallery

Fish Hawk, ca. 1900.

Fish Hawk, ca. 1900. Hoist and winch on Fish Hawk, used by Commissioner Spencer Fullerton Baird and Professor Addison Emery Verrill in exploration of the New England coast, c. 1885.

Hoist and winch on Fish Hawk, used by Commissioner Spencer Fullerton Baird and Professor Addison Emery Verrill in exploration of the New England coast, c. 1885. Albatross in the 1890s.

Albatross in the 1890s.

.jpg) Postcard of U.S. Bureau of Fisheries buildings at Woods Hole, from sometime between ca. 1930 and ca. 1945.

Postcard of U.S. Bureau of Fisheries buildings at Woods Hole, from sometime between ca. 1930 and ca. 1945. SS Roosevelt in 1909, prior to her 1917–1919 service as the "Pribilof tender."

SS Roosevelt in 1909, prior to her 1917–1919 service as the "Pribilof tender."- MV Eider, "Pribilof tender" from 1919 to 1930.

- MV Penguin, "Pribilof tender" from 1930 to 1950.

- MV Penguin (background) at anchor in the Bering Sea in 1939 while she unloads off St. George Island in the Pribilof Islands.

References

- "Spencer Baird and Ichthyology at the Smithsonian: U.S. FISH COMMISSION". Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved September 11, 2017.

- "22.3, General records of the U.S. Fish Commission and the Bureau of Fisheries, 1870-1940", Records of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service [USFWS], The U.S. National Archives and Records Administration, retrieved September 11, 2017

- Stevenson, Charles H. (April 1903). "The United States Fish Commission" (PDF). The North American Review: 593–601. Retrieved September 11, 2017.

- "Fisheries Historical Timeline: Historical Highlights 1900s". NOAA Fisheries Service: Northeast Fisheries Science Center. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). June 16, 2011. Retrieved September 11, 2017.

- "Fisheries Historical Timeline: Historical Highlights 1910s". NOAA Fisheries Service: Northeast Fisheries Science Center. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). June 16, 2011. Retrieved September 11, 2017.

- "Fisheries Historical Timeline: Historical Highlights 1930s". NOAA Fisheries Service: Northeast Fisheries Science Center. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). June 16, 2011. Retrieved September 11, 2017.

- "Fisheries Historical Timeline: Historical Highlights 1940s". NOAA Fisheries Service: Northeast Fisheries Science Center. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). June 16, 2011. Retrieved September 11, 2017.

- "Fisheries Historical Timeline: Historical Highlights 1950s". NOAA Fisheries Service: Northeast Fisheries Science Center. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). June 16, 2011. Retrieved September 11, 2017.

- "Fisheries Historical Timeline: Historical Highlights 1970s". NOAA Fisheries Service: Northeast Fisheries Science Center. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). June 16, 2011. Retrieved September 11, 2017.

- Galtsoff, Paul S., The Story of the Bureau of Commercial Fisheries Biological Laboratory Woods Hole, Massachusetts, Circular 145, Washington, D.C., 1962, p. 115.

- "Pacific Expeditions of the US Fish Commission Steamer Albatross, 1891, 1899–1900, 1904–1905". Harvard University Library Open Collections Program: EXPEDITIONS & DISCOVERIES. Harvard University. Retrieved September 11, 2017.

- Butchko, Thomas R. (April 2002). "Edenton Station, United States Fish and Fisheries Commission" (PDF). National Register of Historic Places - Nomination and Inventory. North Carolina State Historic Preservation Office. Retrieved August 1, 2014.

- "United States Commission of Fish and Fisheries: Annual Reports 1871-1903". 19th & Early 20th Century Marine Ecology & Fisheries Research Reports. Friends of Penobscot Bay. Retrieved September 11, 2017.

- "The Bulletin of the United States Fish Commission. Selected reports 1881-1901". 19th & Early 20th Century Marine Ecology & Fisheries Research Reports. Friends of Penobscot Bay. 2006. Retrieved September 11, 2017.

- United States Commission of Fish and Fisheries (1887), The Fisheries and Fisheries Industries of the United States (PDF), Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, retrieved September 11, 2017

- NOAA Fisheries Alaska Fisheries Science Center AFSC Historical Corner: Early Fisheries Enforcement Patrol Boats (1912-39)

- NOAA Fisheries Alaska Fisheries Science Center AFSC Historical Corner: Osprey, BOF's first Alaska patrol boat

- AFSC Historical Corner: Auklet and Murre, 1917 Sister Patrol Vessels Retrieved September 17, 2018

- NOAA Fisheries Alaska Fisheries Science Center AFSC Historical Corner: Kittiwake, World War I Boat Over 100 Years Old

- NOAA Fisheries Alaska Fisheries Science Center "AFSC Historical Corner: Petrel and Merganser, World War I Boats"

- NOAA Fisheries Alaska Science Fisheries Center AFSC Historical Corner: Widgeon, World War I Boat

- NOAA Fisheries Alaska Fisheries Science Center AFSC Historical Corner: Stream Watchmen

- NOAA Fisheries Alaska Fisheries Science Center AFSC Historical Corner: Aircraft for Enforcement, Surveying & Transportation

- "The Pribilof Islands Tender Vessels". AFSC Historical Corner. Retrieved September 4, 2018.

- afsc.noaa.gov AFSC Historical Corner: Roosevelt, Bureau's First Pribilof Tender Retrieved September 8, 2018

- afsc.noaa.gov AFSC Historical Corner: Eider, Pribilof Tender and Patrol Vessel Retrieved September 7, 2018

- afsc.noaa.gov AFSC Historical Corner: Penguin, Pribilof Tender for 20 Years (1930–50) Retrieved September 7, 2018

- AFSC Historical Corner: Penguin II, Pribilof Islands Tender (1950-64) Retrieved September 6, 2018

- AFSC Historical Corner: Dennis Winn, Auxiliary Pribilof Tender in the 1950s Retrieved September 10, 2018

- AFSC Historical Corner: Pribilof, Bureau's Last Pribilof Tender (1964-75) Retrieved September 4, 2018

| Wikisource has the text of The New Student's Reference Work article about "United States Fish Commission". |