Ultraviolet photography

Ultraviolet photography is a photographic process of recording images by using light from the ultraviolet (UV) spectrum only. Images taken with ultraviolet light serve a number of scientific, medical or artistic purposes. Images may reveal deterioration of art works or structures not apparent under visible light. Diagnostic medical images may be used to detect certain skin disorders or as evidence of injury. Some animals, particularly insects, use ultraviolet wavelengths for vision; ultraviolet photography can help investigate the markings of plants that attract insects, while invisible to the unaided human eye. Ultraviolet photography of archaeological sites may reveal artifacts or traffic patterns not otherwise visible.

Photographs made of various dyes that fluoresce under ultraviolet illumination are also useful.

Overview

Light which is visible to the human eye covers the spectral region from about 400 to 750 nanometers. This is the radiation spectrum used in normal photography. The band of radiation that extends from about 1 nm to 400 nm is known as ultraviolet radiation. UV spectrographers divide this range into three bands:

- near UV (380–200 nm wavelength; abbrev. NUV)

- far UV (or vacuum UV) (200–10 nm; abbrev. FUV or VUV)

- extreme UV (1–31 nm; abbrev. EUV or XUV).

Only near UV is of interest for UV photography, for several reasons. Ordinary air is opaque to wavelengths below about 200 nm, and lens glass is opaque below about 180 nm. UV photographers subdivide the near UV into:

- Long wave UV that extends from 320 to 400 nm, also called UV-A,

- Medium wave UV that extends from 280 to 320 nm, also called UV-B,

- Short wave UV that extends from 200 to 280 nm, also called UV-C.

(These terms should not be confused with the parts of the radio spectrum with similar names.)

There are two ways to use UV radiation to take photographs - reflected ultraviolet and ultraviolet induced fluorescence photography. Reflected ultraviolet photography finds practical use in medicine, dermatology, botany, criminology and theatrical applications.

Sunlight is the most available free UV radiation source for use in reflected UV photography, but the quality and quantity of the radiation depends on atmospheric conditions. A bright and dry day is much richer in UV radiation and is preferable to a cloudy or rainy day.

Another suitable source is electronic flash which can be used efficiently in combination with an aluminium reflector. Some flash units have a special UV absorbing glass over the flash tube, which must be removed before the exposure. It also helps to partly (90%) remove the gold coating of some flash tubes which otherwise suppresses UV.

Most modern UV sources are based on a mercury arc sealed in a glass tube. By coating the tube internally with a suitable phosphor, it becomes an effective long wave UV source.

Recently, UV-LEDs have become available. Grouping several UV-LEDs can produce a strong enough source for reflected UV photography although the emission waveband is typically somewhat narrower than sunlight or electronic flash.

Special UV lamps known as "black light" fluorescence tubes or bulbs also can be used for long wave ultraviolet photography.

Equipment and techniques

Reflected UV photography

In reflected UV photography the subject is illuminated directly by UV emitting lamps (radiation sources) or by strong sunlight. A UV transmitting filter is placed on the lens, which allows ultraviolet light to pass and which absorbs or blocks all visible and infrared light. UV filters are made from special colored glass and may be coated or sandwiched with other filter glass to aid in blocking unwanted wavelengths. Examples of UV transmission filters are the Baader-U filter or the StraightEdgeU ultraviolet bandpass filter, both of which exclude most visible and infrared light. Older filters include the Kodak Wratten 18A, B+W 403, Hoya U-340 and Kenko U-360 most of which need to be used in conjunction with an additional infrared blocking filter. Typically such IR blocking, UV transmissive filters are made from Schott BG-38, BG-39 and BG-40 glass. Filters for use with digital camera sensors must not have any "infrared leak" (transmission in the infrared spectrum); the sensor will pick up reflected infrared radiation as well as ultraviolet, which may obscure the details that would be resolved by ultraviolet alone.

Most types of glass will allow longwave UV to pass, but absorb all the other UV wavelengths, usually from about 350 nm and below. For UV photography it is necessary to use specially developed lenses having elements made from fused quartz or quartz and fluorite. Lenses based purely on quartz show a distinct focus shift between visible and UV light, whereas the fluorite/quartz lenses can be fully corrected between visible and ultraviolet light without focus shift. Examples of the latter type are the Nikon UV-Nikkor 105 mm f/4.5, the Coastal Optics 60 mm f/4.0, the Hasselblad (Zeiss) UV-Sonnar 105 mm, and the Asahi Pentax Ultra Achromatic Takumar 85 mm f/3.5[1]

Suitable digital cameras for reflected UV photography have been reported to be the (unmodified) Nikon D70 or D40 DSLRs, but many others are suitable after having their internal UV and IR blocking filter removed. The Fujifilm FinePix IS Pro digital SLR camera is purpose-designed for ultraviolet (and infrared) photography, with a frequency response rated from 1000-380 nm, although it also responds to somewhat longer and shorter wavelengths. Silicon (from which DSLR sensors are made) can respond to wavelengths between 1100-190 nm.

UV induced fluorescence photography

Photography based on visible fluorescence induced by UV radiation uses the same ultraviolet illumination as in reflected UV photography. However, the glass barrier filter used on the lens must now absorb or block all ultraviolet and infrared light and must permit only the visible radiation to pass. Visible fluorescence is produced in a suitable subject when the shorter, higher energy ultraviolet wavelengths are absorbed, lose some energy and are emitted as longer, lower energy visible wavelengths.

UV induced visible fluorescence photography must take place in a darkened room, preferably with a black background. The photographer should also wear dark-colored clothes for better results. (Many light-colored fabrics also fluoresce under UV.) Any camera or lens may be used because only visible wavelengths are being recorded.

UV can also induce infrared fluorescence and UV fluorescence depending on the subject. For UV induced non-visible fluorescence photography, a camera must be modified in order to capture UV or IR images, and UV or IR capable lenses must be used.

Filters are sometimes added to the UV illumination source to narrow the illuminant waveband. This filter is called an exciter filter, and it allows only the radiation to pass which is needed to induce a particular fluorescence. As before, a barrier filter must also be placed in front of the camera lens to exclude undesired wavelengths.

Forensic use

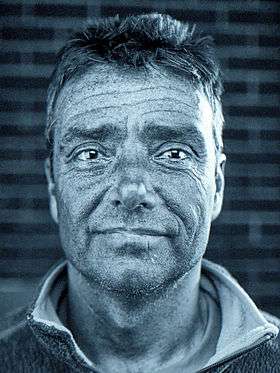

Ultraviolet photography was used as evidence in court at least as early as 1934.[2] Photographs made with ultraviolet radiation can reveal bruises or scars not visible on the surface of the skin, in some cases long after visible healing has completed. These can serve as evidence of assault.[3] Ultraviolet imaging can be used to detect alteration of documents.[4]

See also

- Infrared photography

- Full-spectrum photography

- Robert W. Wood

- Fujifilm FinePix IS PRO UV- (and IR-) sensitive DSLR camera

References

- Medical photography; Clinical-Ultraviolet-Infrared. (1973) Gibson HL, Kodak Company, Rochester, p123-130.

- Larry S. Miller, Norman Marin, Police Photography, Routledge, 2014 ISBN 1317524209. page 5

- Ngaire E. Genge, The Forensic Casebook, Random House Publishing Group, 2002 ISBN 0345461126 page 236

- Donald A. Wilson,Interpreting Land Records, John Wiley & Sons, 2014,ISBN 111874683X, page 313

External links

- UV digital photography

- UV photography of plants, buildings, landscape

- Ultra-violet kite and pole aerial photography

- UltravioletPhotography.com UV floral signatures & other UV photographs.