U.S. presidential impeachment

The Constitution of the United States gives Congress the authority to remove the president of the United States from office in two separate proceedings. The first one takes place in the House of Representatives which impeaches the president by approving articles of impeachment through a simple majority vote. The second proceeding, the impeachment trial, takes place in the Senate. There, conviction on any of the articles requires a two-thirds majority vote and results in the removal from office.[1]

Three United States presidents have been impeached: Andrew Johnson in 1868, Bill Clinton in 1998, and Donald Trump in 2019. All were acquitted by the Senate.

Procedure

Article I, Section 2, Clause 5 of the U.S. Constitution provides:

The House of Representatives ... shall have the sole Power of Impeachment.[1]

Article I, Section 3, Clauses 6 and 7 provide:

The Senate shall have the sole Power to try all Impeachments. When sitting for that Purpose, they shall be on Oath or Affirmation. When the President of the United States is tried, the Chief Justice shall preside: And no Person shall be convicted without the Concurrence of two-thirds of the Members present. Judgment in Cases of Impeachment shall not extend further than to removal from Office, and disqualification to hold and enjoy any Office of honor, Trust or Profit under the United States; but the Party convicted shall nevertheless be liable and subject to Indictment, Trial, Judgment and Punishment, according to Law.[1]

Article II, Section 4 of the U.S. Constitution limits the grounds of impeaching a president to "Treason, Bribery, or other high Crimes and Misdemeanors". Because the precise meaning of the phrase "high crimes and misdemeanors" is not defined in the Constitution itself, it is left open to the interpretation of Congress, especially since the U.S. Supreme Court decided in Nixon v. United States that it did not have the authority to determine whether the Senate properly "tried" a defendant. Congress has, however, identified three general types of conduct that constitute grounds for impeachment, although these categories should not be understood as exhaustive:[1]

- Improperly exceeding or abusing the powers of the office.[1]

- Behavior incompatible with the function and purpose of the office.[1]

- Misusing the office for an improper purpose or for personal gain.[1]

Other than the above constitutional provisions, the exact details of the presidential impeachment process are left up to Congress. Thus, a number of rules have been adopted by the House and Senate and are honored by tradition. Among them, The House Practice: A Guide to the Rules, Precedents and Procedures of the House, prepared by the House Parliamentarian, is a reference source for information on the rules and selected precedents governing the House procedure.[2] Each Congress adopts its own rules.[3] In 1974, as part of the preliminary investigation in the Nixon impeachment inquiry, the staff of the Impeachment Inquiry of the House Judiciary Committee prepared a report, Constitutional Grounds for Presidential Impeachment.[4] This 1974 report has been expanded and revised on several occasions by the Congressional Research Service, now known as Impeachment and Removal.[1] The Senate has formal Rules and Procedures of Practice in the Senate When Sitting on Impeachment Trials.[5] Nevertheless, both the House and the Senate are free to modify the procedures for each presidential impeachment and trial, respectively.[1]

An impeachment proceeding formally begins with a resolution adopted by the full House of Representatives, which typically includes a referral to a House committee to proceed with an impeachment inquiry.[6] The House Judiciary Committee then determines whether grounds for impeachment exist. If the committee finds grounds for impeachment, it will set forth specific allegations of misconduct in one or more articles of impeachment. These articles of impeachment are then reported to the full House with the committee's recommendations.[1]

The House then debates on the article of impeachments, either individually or the full resolution. A simple majority of those present and voting is required for each article for the resolution as a whole to pass. Upon passage, the president has been impeached. The House then selects "House managers" to present the case to the Senate, in a role analogous to the prosecution or district attorney in a standard criminal trial. Finally, the House adopts a resolution to notify formally and present the passed articles of impeachment to the Senate.[1]

The proceedings in the Senate unfold similar to a jury trial, with the chief justice presiding and Senate members acting as the jury. The House managers present their case and the president has the right to mount a defense with their own attorneys. After hearing the charges, the Senate usually deliberates in private before voting whether to convict. A two-thirds super-majority vote is required to remove the president from office.[1]

A two-thirds super-majority vote of conviction only removes the president from office. Following a conviction, the Senate may also vote by a simple majority to punish the individual further by barring them from holding future federal office, elected or appointed.[1] Thus, if the Senate has the required two-thirds super-majority vote to remove a president from office during their first term, it would have to hold a second vote to ban them completely from running for reelection.[7] Once removed, convicted individuals would still be subject to criminal prosecutions in an actual court of law for the same factual situations.[1]

Presidents who were impeached

Summary

Three presidents have been impeached in U.S. history: Andrew Johnson in 1868, Bill Clinton in 1998, and Donald Trump in 2019. Johnson, Clinton and Trump were not removed from office.[8]

Chief justices who presided over presidential impeachment trials

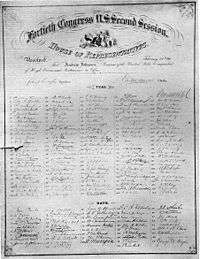

Andrew Johnson (impeached Feb. 1868, acquitted May 1868)

President Andrew Johnson held open disagreements with Congress, who tried to remove him several times. The Tenure of Office Act was enacted over Johnson's veto to curb his power and he openly violated it in early 1868.[12]

The House of Representatives adopted 11 articles of impeachment against Johnson. The articles charged Johnson with:

- Dismissing Secretary of War Edwin Stanton from office after the Senate had voted not to concur with his dismissal and had ordered him reinstated.

- Appointing Adjutant General Lorenzo Thomas as secretary of war ad interim despite the lack of vacancy in the office, since the dismissal of Stanton had been invalid.

- Appointing Thomas without the required advice and consent of the Senate.

- Conspiring, with Thomas and "other persons to the House of Representatives unknown," to unlawfully prevent Stanton from continuing in office.

- Conspiring to unlawfully curtail faithful execution of the Tenure of Office Act.

- Conspiring to "seize, take, and possess the property of the United States in the Department of War."

- Conspiring to "seize, take, and possess the property of the United States in the Department of War" with specific intent to violate the Tenure of Office Act.

- Issuing to Thomas the authority of the office of secretary of war with unlawful intent to "control the disbursements of the moneys appropriated for the military service and for the Department of War."

- Issuing to Major General William H. Emory orders with unlawful intent to violate federal law requiring all military orders to be issued through the General of the Army.

- Making three speeches with intent to "attempt to bring into disgrace, ridicule, hatred, contempt and reproach, the Congress of the United States."

- Unlawfully, and unconstitutionally, challenged the authority of the 39th Congress to legislate, because Southern states had not been readmitted to the Union.[13]

Chief Justice Salmon P. Chase presided over Johnson's Senate trial. Conviction failed by one vote in May 1868. The impeachment trial remained a unique event for 130 years.[14]

Bill Clinton (impeached Dec. 1998, acquitted Feb. 1999)

Two articles of impeachment were approved by the House, charging President Bill Clinton with perjury and obstruction of justice.[15] The charges stemmed from a sexual harassment lawsuit filed against Clinton by Arkansas state employee Paula Jones and from Clinton's testimony denying that he had engaged in a sexual relationship with White House intern Monica Lewinsky. They were:

Article I, charging Clinton with perjury, alleged in part that:

On August 17, 1998, William Jefferson Clinton swore to tell the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth before a federal grand jury of the United States. Contrary to that oath, William Jefferson Clinton willfully provided perjurious, false and misleading testimony to the grand jury concerning one or more of the following:

- the nature and details of his relationship with a subordinate government employee;

- prior perjurious, false and misleading testimony he gave in a federal civil rights action brought against him;

- prior false and misleading statements he allowed his attorney to make to a federal judge in that civil rights action; and

- his corrupt efforts to influence the testimony of witnesses and to impede the discovery of evidence in that civil rights action.[16][17]

Article II, charging Clinton with obstruction of justice alleged in part that:

The means used to implement this course of conduct or scheme included one or more of the following acts:

- ... corruptly encouraged a witness in a Federal civil rights action brought against him to execute a sworn affidavit in that proceeding that he knew to be perjurious, false and misleading.

- ... corruptly encouraged a witness in a Federal civil rights action brought against him to give perjurious, false and misleading testimony if and when called to testify personally in that proceeding.

- ... corruptly engaged in, encouraged, or supported a scheme to conceal evidence that had been subpoenaed in a Federal civil rights action brought against him.

- ... intensified and succeeded in an effort to secure job assistance to a witness in a Federal civil rights action brought against him in order to corruptly prevent the truthful testimony of that witness in that proceeding at a time when the truthful testimony of that witness would have been harmful to him.

- ... at his deposition in a Federal civil rights action brought against him, William Jefferson Clinton corruptly allowed his attorney to make false and misleading statements to a Federal judge characterizing an affidavit, in order to prevent questioning deemed relevant by the judge. Such false and misleading statements were subsequently acknowledged by his attorney in a communication to that judge.

- ... related a false and misleading account of events relevant to a Federal civil rights action brought against him to a potential witness in that proceeding, in order to corruptly influence the testimony of that witness.

- ... made false and misleading statements to potential witnesses in a Federal grand jury proceeding in order to corruptly influence the testimony of those witnesses. The false and misleading statements made by William Jefferson Clinton were repeated by the witnesses to the grand jury, causing the grand jury to receive false and misleading information.[16][18]

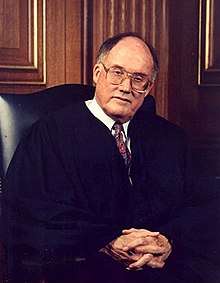

Chief Justice William Rehnquist presided over Clinton's Senate trial. As both articles of impeachment failed to receive the required super-majority, Clinton was acquitted and was not removed from office.[19]

Donald Trump (impeached Dec. 2019, acquitted Feb. 2020)

After a whistleblower accused President Donald Trump of pressuring a foreign government to interfere on Trump's behalf in the 2020 election, the House initiated an impeachment inquiry.[20][21] On December 10, 2019, the Judiciary Committee approved two articles of impeachment (H.Res. 755): abuse of power and obstruction of Congress.[22] On December 18, 2019, the House voted to impeach Trump on two charges:[23]

- Abuse of power by "pressuring Ukraine to investigate his political rivals ahead of the 2020 election while withholding a White House meeting and $400 million in U.S. security aid from Kiev."[24]

- Obstruction of Congress by directing defiance of subpoenas issued by the House and ordering officials to refuse to testify.[24]

On February 5, 2020, the Senate found Trump not guilty of abuse of power, by a vote of 48-52, with Republican senator Mitt Romney being the only senator—and the first senator in U.S. history—to cross party lines by voting to convict,[25][26] and not guilty of obstruction of Congress, by a vote of 47-53.[25][26]

Chief Justice John Roberts presided over Trump's Senate trial. As both articles of impeachment failed to receive the required super-majority, Trump was acquitted and was not removed from office.[26]

Presidents subjected to an impeachment process who resigned before it ended

President Richard Nixon was subjected to an impeachment process. To avoid likely impeachment and conviction, he resigned on August 9, 1974.[8]

Richard Nixon (initiated Oct. 1973, resigned Aug. 1974)

The House Judiciary Committee approved three articles of impeachment against President Richard Nixon for obstruction of justice, abuse of power and contempt of Congress.

On October 30, 1973, Nixon ordered the firing of Special Prosecutor Archibald Cox, precipitating the Saturday Night Massacre. A massive reaction took place, especially in Congress, where 17 resolutions were introduced between November 1, 1974, and January 1974: H.Res. 625, H.Res. 635, H.Res. 643, H.Res. 648, H.Res. 649, H.Res. 650, H.Res. 652, H.Res. 661, H.Res. 666, H.Res. 686, H.Res. 692, H.Res. 703, H.Res. 513, H.Res. 631, H.Res. 638, and H.Res. 662.[27][28] H.Res. 803, passed February 6, authorizes a Judiciary Committee investigation.[29] In July, the House Judiciary Committee voted three articles of impeachment to the House floor, designated H.Rept. 1305. The impeachment proceedings against Nixon were mooted when Nixon resigned on August 9, 1974. A report containing articles of impeachment was accepted by the full House on August 20, 1974, by a vote of 412–3.[30]

While Nixon was never impeached, this remains the only successful impeachment process, as its intended effect was carried out when Nixon resigned from office.

Presidents who, after a formal investigation, were not impeached

John Tyler

Rep. John Botts (Whig-VA), who opposed President John Tyler, introduced an impeachment resolution on July 10, 1842. It levied several charges against Tyler regarding his use of the presidential veto power and called for a nine-member committee to investigate his actions, with the expectation of a formal impeachment recommendation.[31] The impeachment resolution was defeated, 83–127.[32]

James Buchanan

The House of Representatives set up the United States House Select Committee to Investigate Alleged Corruptions in Government, known as the Covode Committee after its chairman, Rep. John Covode (R-PA), to investigate President James Buchanan on suspicion of bribery and other allegations. After about a year of hearings, the committee concluded that Buchanan's actions did not merit impeachment.[33]

Harry S. Truman

On April 22, 1952, Rep. Noah M. Mason (R-IL) suggested that impeachment proceedings should be started against President Harry S. Truman for seizing the nation's steel mills. Soon after Mason's remarks, Rep. Robert Hale (R-ME) introduced a resolution (H.Res. 604).[34][35] After three days of debate on the floor of the House, it was referred to the House Judiciary Committee where it died.[36]

Ronald Reagan

On March 5, 1987, Rep. Henry B. González (D-TX) introduced H.Res. 111, with six articles against President Ronald Reagan regarding the Iran-Contra affair. While no further action was taken on this particular bill,[37] it led directly to the joint hearings of the subject that dominated the news later that year.[36][38] After the hearings were over, it was reported in USA Today that articles of impeachment were being discussed, but it was decided against.

Presidents against whom impeachment resolutions were introduced, but no action was taken

Many presidents have been subject to demands for impeachment by groups and individuals.[39][40][41][42][43]

Ulysses S. Grant

Rep. Joseph Clay Stiles Blackburn (D-KY) introduced an impeachment resolution against President Ulysses S. Grant in 1876, regarding the number of days Grant had been absent from the White House. The resolution never gained momentum and was tabled in December 1876.[44]

Grover Cleveland

Rep. Milford W. Howard (D-AL), on May 23, 1896, submitted a resolution (H.Res 374) impeaching President Grover Cleveland for selling unauthorized federal bonds and breaking the Pullman Strike. It was neither voted on nor referred to a committee.[36]

Herbert Hoover

in 1932 and early 1933, Rep. Louis Thomas McFadden (R-PA) introduced two impeachment resolutions against President Herbert Hoover, which were considered for several hours and were then tabled.[36]

Lyndon B. Johnson

On May 3, 1968, a petition to impeach President Lyndon B. Johnson was accepted by the House Judiciary Committee.[45] Nothing further was done on the matter.

George H.W. Bush

President George H. W. Bush[46] was subject to two resolutions over the Gulf War in 1991, both by Rep. Henry B. González (D-TX).[36][27] H.Res. 34 was introduced on January 16, 1991, and was referred to the House Committee on Judiciary and then its Subcommittee on Economic and Commercial Law on March 18, 1992.[47] H.Res. 86 on February 21, 1991, and referred to the House Judiciary Committee.[48]

George W. Bush

During the administration of President George W. Bush, several American politicians sought to either investigate him for possible impeachable offenses or to bring actual impeachment charges on the floor of the House Judiciary Committee. The most significant of these occurred on June 10, 2008, when Rep. Dennis Kucinich (D-OH) and Rep. Robert Wexler (D-FL) introduced H.Res. 1258, containing 35 articles of impeachment[49] against Bush, to the House.[50] After nearly a day of debate, the House voted 251–166 to refer the impeachment resolution to the House Judiciary Committee on June 11, 2008, where no further action was taken on it.[51] Bush's second term in office ended on January 20, 2009, rendering impeachment efforts moot.[52]

Barack Obama

On December 3, 2013, the House Judiciary Committee held a hearing on President Barack Obama that was formally titled "The President's Constitutional Duty to Faithfully Execute the Laws," which has been viewed as an attempt to begin justifying impeachment proceedings. When asked by reporters if this was a hearing about impeachment, Rep. Lamar Smith (R-TX) responded that it was not, saying "I didn't mention impeachment nor did any of the witnesses in response to my questions at the Judiciary Committee hearing."[53][54][55]

See also

- Impeachment in the United States

- Impeachment investigations of United States federal officials

- List of presidential impeachments

References

- Cole, J. P.; Garvey, T. (October 29, 2015). "Report No. R44260, Impeachment and Removal" (PDF). Congressional Research Service. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 19, 2019. Retrieved September 22, 2016.

- "The House Practice: A Guide to the Rules, Precedents and Procedures of the House". Parliamentarian of the House. U.S. House of Representatives. Archived from the original on December 21, 2019. Retrieved December 21, 2019.

- "The House Practice: A Guide to the Rules, Precedents and Procedures of the House". Parliamentarian of the House. U.S. House of Representatives. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved December 21, 2019.

- Staff of the Impeachment Inquiry, Committee on the Judiciary, House of Representatives, Constitutional Grounds for Presidential Impeachment, 93rd Conf. 2nd Sess. (Feb. 1974), 1974 Impeachment Inquiry Report

- "Rules and Procedures of Practice in the Senate When Sitting on Impeachment Trials" (PDF). Senate Manual Containing the Standing Rules, Orders, Laws and Resolutions Affecting the Business of the United States Senate. United States Senate. August 16, 1986. Section 100–126, 105th Congress, pp. 177–185. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 19, 2019. Retrieved June 14, 2018.

- "Impeachment and Removal". everycrsreport.com. Archived from the original on November 15, 2019. Retrieved December 21, 2019.

- Panetta, Grace (December 18, 2019). "Here's how Trump could be impeached, removed from office, and still win re-election in 2020". Business Insider. Archived from the original on December 21, 2019. Retrieved January 3, 2020.

- Cai, Weiyi (December 18, 2019). "What is the impeachment process? A step by step guide". The New York Times. Archived from the original on December 21, 2019. Retrieved December 21, 2019.Wagner, John; Bruce-Sadler, Michael (December 23, 2019). "McConnell, Pelosi dig in on impasse over Trump's Senate trial". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on December 23, 2019. Retrieved December 20, 2019.

- http://www.let.rug.nl/usa/biographies/salmon-portland-chase/impeachment-trial-of-president-andrew-johnson.php

- https://www.cnn.com/2019/09/29/politics/william-rehnquist-impeachment-trial-senate/index.html

- https://www.rawstory.com/2020/01/gop-ex-congressman-calls-on-justice-roberts-to-override-republican-effort-to-block-witnesses/

- "Impeachment: Andrew Johnson". The History Place. Archived from the original on November 9, 2019. Retrieved December 24, 2019.

- "98-763 GOV Congressional Resolutions on Presidential Impeachment: A Historical Overview" (PDF). digital.library.unt.edu. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 2, 2019. Retrieved January 14, 2020.

- Editors, History com. "President Clinton impeached". HISTORY. Archived from the original on November 21, 2019. Retrieved December 21, 2019.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- landmarkcases.dcwdbeta.com, Landmark Supreme Court Cases (555) 123-4567. "Landmark Supreme Court Cases | Articles of Impeachment against President Clinton, 1998". Landmark Supreme Court Cases. Archived from the original on December 21, 2019. Retrieved December 21, 2019.

-

- Text of Article I Archived December 16, 2017, at the Wayback Machine Washington Post December 20, 1998

- Text of Article IIII Archived December 16, 2017, at the Wayback Machine Washington Post December 20, 1998

- Baker, Peter; Dewar, Helen (February 13, 1999). "The Senate Acquits President Clinton". Washington Post. Archived from the original on November 10, 2013. Retrieved December 26, 2019.

- Przybyla, Heidi; Edelman, Adam (September 24, 2019). "Nancy Pelosi announces formal impeachment inquiry of Trump". NBC News. Archived from the original on September 24, 2019. Retrieved September 24, 2019.

- Schmidt, Michael S.; Barnes, Julian E.; Haberman, Maggie (November 26, 2019). "Trump Knew of Whistle-Blower Complaint When He Released Aid to Ukraine". The New York Times. Archived from the original on November 29, 2019. Retrieved December 26, 2019.

- "Read the Articles of Impeachment against President Trump". The New York Times. December 13, 2019. Archived from the original on December 10, 2019. Retrieved December 26, 2019.

- Shear, Michael D.; Baker, Peter (December 19, 2019). "Trump Impeachment Vote Live Updates: House Votes to Impeach Trump for Abuse of Power". The New York Times. Archived from the original on December 19, 2019. Retrieved December 26, 2019.

- Herb, Jeremy; Raju, Manu (December 19, 2019). "House of Representatives impeaches President Donald Trump". CNN. Archived from the original on December 26, 2019. Retrieved December 26, 2019.

- Fandos, Nicholas (February 5, 2020). "Trump Acquitted of Two Impeachment Charges in Near Party-Line Vote". The New York Times. Retrieved February 7, 2020.

- "How senators voted on Trump's impeachment". Politico. February 7, 2020. Retrieved February 5, 2020.

- "Congressional Resolutions on Presidential Impeachment: A Historical Overview". everycrsreport.com. Archived from the original on December 20, 2019. Retrieved December 20, 2019.

- "The History Place - Impeachment: Richard Nixon". www.historyplace.com. Archived from the original on December 16, 2019. Retrieved December 19, 2019.

- "H.Res.803 - 93rd Congress (1973-1974): Resolution providing appropriate power to the Committee on the Judiciary to conduct an investigation of whether sufficient grounds exist to impeach Richard M. Nixon, President of the United States". www.congress.gov. February 6, 1974. Archived from the original on December 19, 2019. Retrieved December 20, 2019.

- "The Nixon Impeachment Proceedings". LII / Legal Information Institute. Archived from the original on December 9, 2019. Retrieved December 19, 2019.

- Lucas, Fred (December 22, 2019). "A Lesson for Trump? When Impeaching A President Doesn't Go As Planned". nationalinterest.org. Retrieved January 14, 2020.

- "Impeachment Grounds: Part 5: Selected Douglas/Nixon Inquiry Materials". everycrsreport.com. Archived from the original on June 22, 2019. Retrieved December 20, 2019.

- Zeitz, Joshua. "What Democrats Can Learn From the Forgotten Impeachment of James Buchanan". POLITICO. Archived from the original on December 19, 2019. Retrieved December 19, 2019.

- "H.Res. 604". 82nd Congress 2nd Session.

- "Seizure of Steel Mills". Remarks in The: House, Congressional Record. 98: 4222–4240. April 22, 1952.

- Baker, Peter (November 30, 2019). "Long Before Trump, Impeachment Loomed Over Multiple Presidents". New York Times. Archived from the original on December 3, 2019. Retrieved December 3, 2019.

- Baker, Peter (November 30, 2019). "Long Before Trump, Impeachment Loomed Over Multiple Presidents". nytimes.com. Archived from the original on December 3, 2019. Retrieved January 14, 2020.

- McManus, Doyle (June 15, 1987). "Reagan Impeachment Held Possible : It's Likely if He Knew of Profits Diversion, Hamilton Says". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on December 6, 2019. Retrieved December 6, 2019.

- "The Pittsburgh Press - Google News Archive Search". news.google.com.

- "Tentative Description of a Dinner Given to Promote the Impeachment of President Eisenhower". www.citylights.com. Archived from the original on March 23, 2015. Retrieved December 10, 2019.

- Epstein, Jennifer. "Kucinich: Libya action 'impeachable'". POLITICO. Archived from the original on November 8, 2014. Retrieved December 28, 2019.

- "Censured but not impeached". Miller Center. October 3, 2019. Archived from the original on December 20, 2019. Retrieved December 20, 2019.

- "Impeaching James K. Polk | History News Network". historynewsnetwork.org. Archived from the original on December 20, 2019. Retrieved December 20, 2019.

- "'Why We Laugh' Pro Tem". Harper's Weekly. Archived from the original on October 2, 2013. Retrieved June 22, 2013.

- "Johnson Impeachment Asked". timesmachine.nytimes.com.

- Meacham, Jon. "The Hidden Hard-line Side of George H.W. Bush". POLITICO Magazine.

- "H.Res.34 - Impeaching George Herbert Walker Bush, President of the United States, of high crimes and misdemeanors". congress.gov. Retrieved January 14, 2020.

- "H.Res.86 - Impeaching George Herbert Walker Bush, President of the United States, of high crimes and misdemeanors". congress,gov. Archived from the original on August 25, 2018. Retrieved January 14, 2010.

- "H. Res. 1258, 110th Cong". 2008. Archived from the original on October 15, 2008. Retrieved December 15, 2019.

- Man, Anthony (June 10, 2008). "Impeach Bush, Wexler says". South Florida Sun-Sentinel.com. Archived from the original on May 22, 2016. Retrieved June 10, 2008.

- Kucinich, Dennis J. (June 11, 2008). "Actions - H.Res.1258 - 110th Congress (2007-2008): Impeaching George W. Bush, President of the United States, of high crimes and misdemeanors". www.congress.gov. Archived from the original on December 28, 2019. Retrieved December 28, 2019.

- "Barack Obama's Inauguration - Photo Essays". TIME.com. Archived from the original on December 21, 2019. Retrieved December 21, 2019.

- "Enough with impeachment blatherings – San Antonio Express-News". Mysanantonio.com. December 6, 2013. Archived from the original on December 10, 2019. Retrieved May 16, 2014.

- Milbank, Dana (December 3, 2013). "Republicans see one remedy for Obama — impeachment". Washington Post. Archived from the original on December 4, 2019. Retrieved December 3, 2019.

- "Impeach Obama! (And FDR, Eisenhower, Carter, Reagan, Etc.)". NPR.org. Archived from the original on December 9, 2019. Retrieved December 9, 2019.

.jpg)