Treaty of Madrid (1667)

The Treaty of Madrid, also known as The Earl of Sandwich's Treaty, was signed on 23 May, 1667 by England and Spain. It was one of a series of agreements made in response to French expansion under Louis XIV.

| |

| Context | Spain and England undertake not to assist enemies of the other; England agrees to mediate an end to the Portuguese Restoration War; Spain awards England commercial privileges |

|---|---|

| Signed | 23 May 1667 |

| Location | Madrid |

| Condition | 21 September 1667 |

| Negotiators | |

| Signatories | |

| Parties | |

| Ratifiers | |

| Language | Latin |

The parties agreed commercial terms allowing English merchants trading privileges within the Spanish Empire, which remained in place until superseded by the Treaty of Utrecht in 1714. They undertook not to assist each other's enemies, while England also agreed to mediate an end to the 1640 to 1668 Portuguese Restoration War; this resulted in the 1668 Treaty of Lisbon between Spain and Portugal.

The issue of Spanish possessions captured by England in the 1654-60 Anglo-Spanish War were settled in the subsequent 1670 Treaty of Madrid.

Background

The treaty was one of a series of agreements signed between 1662 and 1668, driven by changes in the European balance of power. These included the weakening of the relationship between France and the Dutch Republic, allies in the Eighty Years' War, and Spain's eclipse by France under Louis XIV.[1]

By the middle of the 17th century, the Spanish Empire remained a huge global confederation but needed peace after a century of continuous warfare. The Franco-Spanish War of 1635-59 concluded with the Treaty of the Pyrenees; the Anglo-Spanish War of 1654-60 involving the Commonwealth of England was suspended after the Restoration of Charles II in 1660.[2]

Spain now focused on ending the long-running Portuguese Restoration War; in 1656, Philip IV agreed to help Charles regain his throne, in return for assistance against Portugal. However, in May 1661, Charles agreed to marry Catherine of Braganza and provide Portugal military support.[3]

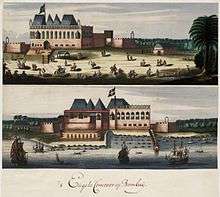

This was the result of various factors, one being Philip's insistence on the return of Jamaica, captured in 1656, and Dunkirk, captured in 1658; previously part of the Spanish Netherlands, Charles sold it to France in 1662. Relinquishing Jamaica was viewed with great hostility in England, where Parliament voted to annex it in September 1660. English merchants gained access to Portuguese markets in Brazil, Africa and the Far East; the acquisition of Tangier and Bombay provided bases in the Mediterranean and on the Surat coast. This made it too attractive to refuse but impacted Anglo-Spanish relations.[4]

Negotiations

Sir Richard Fanshawe, English ambassador in Portugal from 1662 to 1666, was also appointed ambassador to Spain in 1664. He was instructed to agree a treaty of commerce, obtain reparations for losses and confirm possession of territories captured from 1654 to 1660, primarily Jamaica.[5]

In 1663, Philip launched a major military offensive against Portugal and refused to negotiate while England was assisting 'rebels'.[6] Talks opened in 1664 when the offensive failed, halted when the Second Anglo-Dutch War began in March 1665, then restarted following Spanish defeat at the Battle of Montes Claros in June.[7] Philip died in September, leaving his three year old son Charles II as king, and his wife Mariana of Austria as regent.[8]

Ending the war with Portugal was a priority for the new Spanish government and Juan Nithard made an Anglo-Spanish treaty dependent on English help in achieving this. However, Louis encouraged Portugal to insist on harsh terms, seeking to prevent Spain reinforcing the Spanish Netherlands.[9]

In December, Fanshawe finalised terms with Count Peñaranda, a member of the Spanish Regency Council, using the 1630 Treaty of Madrid as a base. They were unaware of discussions in London between the Spanish ambassador, Count Molina, the Duke of York and Arlington. Charles refused to ratify Fanshawe's version, claiming he had exceeded instructions and replaced him with Lord Sandwich. Fanshawe died in June 1666, shortly before returning home.[10]

In March 1667, France and Portugal signed the Treaty of Lisbon, a ten year offensive and defensive alliance against Spain; on 24 May, French troops entered the Spanish Netherlands in the War of Devolution. Facing the prospect of years of war with Portugal and the loss of their provinces to France, Spain now quickly came to terms.[11]

Terms

The prominence of commercial issues in 17th and 18th century diplomacy derived from the economic theory of Mercantilism, which viewed global trade as finite. Increasing your share meant taking it from others, so states protected their own using tariffs or import bans, while attacking the colonies or ships of others.[12] English complaints related to two areas; exclusion from markets within the Spanish Empire, and restrictions on direct trade between mainland Spain and England.[13]

The 1630 treaty was annulled and on 23 May 1667, England and Spain signed two new treaties; a commercial deal and an agreement by England to mediate a truce between Portugal and Spain.[14] In a separate article, each party undertook not to assist enemies of the other; England would withdraw its Portuguese expeditionary force, while Spain remained neutral in the Anglo-Dutch war.[15]

The commercial treaty consisted of forty separate articles, the most important being Article Seven, part of Fanshawe's draft but omitted from the original terms.[15] English merchants were given equal status with the Dutch and granted the right to import goods tax free into European Spain.[16] Articles Seven, Eight, Eleven and Twelve went further than this, by allowing English colonies in North America and the East India Company to ship goods direct to Spanish ports.[13]

By granting English merchants trading rights within Spanish America, the treaty accepted England's presence in the Caribbean and occupation of Jamaica, although this was not formally recognised until 1670. Article Ten broadly exempted English ships and warehouses in Spanish ports from customs inspections, disputes being referred to a local judge, nominated by the English and confirmed by Madrid.[17]

Articles Fourteen through Seventeen allowed English ships access to ports throughout the Spanish Empire, a significant concession since it greatly increased their operating range.[13] Article Thirty-Eight made English merchants equivalent to the Dutch and French by awarding them most favoured nation status; its implementation was resisted by Spanish merchants and had to be re-iterated in the 1670 Treaty.[18]

These concessions were the first step in challenging Dutch economic supremacy outside Europe and thus of greater significance than often appreciated; they remained in place until the outbreak of the War of the Spanish Succession in 1701.[19]

Aftermath

Economic historian Guillermo Pérez Sarrión claims the 1667 treaty demonstrates 'England's absolute dominance of Anglo-Spanish trade'.[20] One London merchant later described it as ‘the best flower in our garden'; English goods were imported through Cadiz, then sold locally or re-exported to the colonies, Spanish dye and wool going the other way.[21]

Franco-Spanish trade primarily consisted of bulk imports like grain and timber, which were easily regulated by local authorities. English trade was predominantly maritime, within the vast Spanish Empire, and much harder to control; the treaty effectively permitted ships captains to decide what goods were listed on their manifest as 'English'.[22] This allowed English merchants to evade customs duties, demand from Spanish colonists creating a large and extremely profitable black market.[23]

In September, Afonso VI of Portugal was deposed in a coup led by his brother Pedro; the previous treaty with France was annulled and with England as mediator, Spain and Portugal signed the Treaty of Lisbon on 13 February 1668.[24] Relieved of this burden and backed by the Triple Alliance, Spain ended the War of Devolution with France by agreeing the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle on 5 May.[25]

The question of Spanish possessions in the West Indies captured by England in the previous war was later settled in the 1670 Treaty of Madrid.[14]

References

- Israel 1989, pp. 197-198.

- Davenport & Paullin 1917, p. 50.

- Belcher 1975, pp. 70-71.

- Belcher 1975, pp. 72-73.

- Riley 2014, p. 58.

- Davenport & Paullin 1917, p. 94.

- Riley 2014, pp. 122-123.

- Cowans 2003, pp. 26–27.

- Geyl 1936, pp. 311-312.

- Lockey 2016, p. 260.

- Feiling 2013, pp. 232-234.

- Rothbard, Murray. "Mercantilism as the Economic Side of Absolutism". Mises.org. Retrieved 30 November 2019.

- McLachlan 1934, p. 299.

- Fisher & Savelle 1967, pp. 66-70.

- Davenport & Paullin 1917, pp. 96-98.

- Andrien & Kuethe 2014, pp. 50-52.

- Andrien & Kuethe 2014, p. 50.

- Stein & Stein 2000, p. 63.

- Lodge 1932, p. 3.

- Sarrion 2016, p. 57.

- Mclachlan 1940, p. 6.

- Sarrion 2016, p. 58.

- Richmond 1920, p. 2.

- Newitt 2004, p. 228.

- Davenport & Paullin 1917, p. 144.

Sources

- Andrien, Kenneth J; Kuethe, Allan J (2014). The Spanish Atlantic World in the Eighteenth Century: War and the Bourbon Reforms, 1713–1796. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781107043572.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Belcher, Gerald (1975). "Spain and the Anglo-Portuguese Alliance of 1661: A Reassessment of Charles II's Foreign Policy at the Restoration". British Studies. 15 (1): 67–88. doi:10.1086/385679. JSTOR 175239.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Cowans, Jon (2003). Modern Spain: A Documentary History. U. of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 0-8122-1846-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Davenport, Frances Gardiner; Paullin, Charles Oscar, eds. (1917). European Treaties Bearing on the History of the United States and Its Dependencies, Vol. 2: 1650-1697 (2018 ed.). Forgotten Books. ISBN 978-0483158924.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Feiling, Keith (2013). British Foreign Policy 1660-1972. Routledge. ISBN 9781136241543.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Fisher, Margaret Anne; Savelle, Max (1967). The origins of American diplomacy: the international history of Angloamerica, 1492-1763 American diplomatic history series Authors. Macmillan.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Geyl, P (1936). "Johan de Witt, Grand Pensionary of Holland, 1653–72". History. 20 (80): 303–319. doi:10.1111/j.1468-229X.1936.tb00103.x. JSTOR 24401084.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Israel, Jonathan (1989). Dutch Primacy in World Trade, 1585–1740 (1990 ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0198211396.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lockey, Brian C (2016). Early Modern Catholics, Royalists, and Cosmopolitans: English Transnationalism and the Christian Commonwealth Transculturalisms, 1400-1700. Routledge. ISBN 9781317147107.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lodge, Richard (1932). "Presidential Address: Sir Benjamin Keene, K.B.: A Study in Anglo-Spanish Relations in the Earlier Part of the Eighteenth Century". Transactions of the Royal Historical Society. 15: 1–43. doi:10.2307/3678642. JSTOR 3678642.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Mclachlan, Jean O (1940). Trade and Peace with Old Spain (2015 ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1107585614.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- McLachlan, Jean (1934). "Documents Illustrating Anglo-Spanish Trade between the Commercial Treaty of 1667 and the Commercial Treaty and the Asiento Contract of 1713". Cambridge Historical Journal. 4 (3): 299–311. doi:10.1017/S1474691300000664. JSTOR 3020673.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Newitt, Malyn (2004). A History of Portuguese Overseas Expansion 1400–1668. Routledge. ISBN 9781134553044.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Richmond, Herbert (1920). The Navy in the War of 1739-48 - War College Series (2015 ed.). War College Series. ISBN 978-1296326296.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Riley, Jonathon (2014). The Last Ironsides: The English Expedition to Portugal, 1662-1668. Helion & Company. ISBN 978-1909982208.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sarrion, Guillermo Perez (2016). The Emergence of a National Market in Spain, 1650-1800: Trade Networks, Foreign Powers and the State. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 9781472586469.

- Stein, Stanley J; Stein, Barbara H (2000). Silver, Trade, and War: Spain and America in the Making of Early Modern Europe. JHU Press. ISBN 9780801861352.