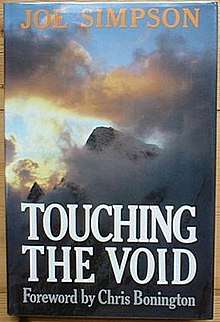

Touching the Void (book)

Touching the Void is a 1988 book by Joe Simpson, recounting his and Simon Yates' successful but disastrous and nearly fatal climb of the 6,344-metre (20,814 ft) Siula Grande in the Peruvian Andes in 1985. It has sold over a million copies and has been translated into over 20 languages[1]. In 2013 the 25th Anniversary eBook edition of Touching the Void was published by DirectAuthors.com. It features additional photography from the expedition.

Plot

In 1985, Simpson and Yates reached the summit of the previously unclimbed west face of Siula Grande. Upon descent, Simpson slipped down an ice cliff and landed awkwardly, breaking his right leg and crushing his tibia into his knee joint. The pair, whose trip had already taken longer than they intended due to bad weather on the ascent, had run out of fuel for their stove and could not melt ice or snow for drinking water. With bad weather closing in and daylight fading, they needed to descend quickly to the glacier, about 3,000 feet (900 m) below.

Yates proceeded to lower Simpson off the North Ridge by tying two 150-foot (46 m) lengths of rope together to make one 300-foot (91 m) rope. However, because the two ropes were tied together, the knot could not go through the belay plate. Simpson would have to stand on his good leg to give Yates enough slack to unclip the rope, in order to thread the rope back through the lowering device with the knot on the other side. With storm conditions worsening and darkness upon them, Yates inadvertently lowered Simpson off a cliff. Because Yates was sitting higher up the mountain, he could not see nor hear Simpson; he could only feel that Simpson had all his weight on the rope. Simpson attempted to ascend the rope using a Prusik knot. However, because his hands were badly frostbitten, he was unable to tie the knots properly and accidentally dropped one of the cords required to ascend the rope.

The pair were both in mortal danger. Simpson could not climb up the rope, Yates could not pull him back up, the cliff was too high for Simpson to be lowered down, and they could not communicate. They remained in this position for some time, until it was obvious to Yates that the snow around his belay seat was about to give out. Because the pair were tied together, they would both be pulled to their deaths. Yates had to cut the rope in order to save his own life. Simpson plummeted down the cliff and into a deep crevasse. Exhausted and suffering from hypothermia, Yates dug himself a snow cave to wait out the storm. The next day, Yates carried on descending the mountain by himself. When he reached the crevasse he realized the situation that Simpson had been in and what had happened when he cut the rope. After calling for Simpson and hearing no reply, Yates made the assumption that Simpson had died and so continued down the mountain alone.

Simpson, however, was still alive. He had survived the 150-foot (46 m) fall despite his broken leg and had landed on a small ledge inside the crevasse. When he regained consciousness, he discovered that the rope had been cut and realized that Yates would presume that he was dead. He therefore had to save himself. It was impossible for him to climb up to the entrance of the crevasse, because of the overhanging ice and his broken leg. Therefore, his only choice was to lower himself deeper into the crevasse and hope that there was another way out. After lowering himself, Simpson found another small entrance and climbed back onto the glacier via a steep snow slope.

From there, Simpson spent three days without food and with almost no water, crawling and hopping five miles (8 km) back to their base camp. This involved navigating the glacier (which was scattered with more crevasses) and the moraines below. Exhausted and delirious, he reached base camp only a few hours before Yates intended to leave the base camp and return to civilization.

Simpson's survival is regarded by mountaineers as amongst the most remarkable instances of survival against the odds.[2]

Awards

The book won the 1989 Boardman Tasker Prize for Mountain Literature[3] and the 1989 NCR Book Award.

Adaptations

In 2003, fifteen years after it was first published, the book was turned into a documentary film of the same name, directed by Kevin MacDonald. The film won the Alexander Korda Award for Best British Film at the 2003 BAFTA Awards [4] and was featured at the 2004 Sundance Film Festival.[5] In 2014, the book was being used in the English literature AQA GCSE course nationally in England.

In 2017, it was announced the book was being adapted for the stage by David Greig[6] and that the play would receive its world premiere the following year[7] and would begin previews at the Bristol Old Vic on 8 September 2018,[8] with an official opening night on 18 September,[9] booking for a limited period until 6 October.[8]

Notes

- http://www.parliamentspeakers.com/News/Touching%20the%20Void%20book%20review%20%20Joe%20Simpson

- Mountaineering: The Making of Touching the Void | Mountaineering. OutsideOnline.com. Retrieved on 2012-06-23.

- The Boardman Tasker Prize Archived 2009-02-25 at the Wayback Machine. Boardmantasker.com. Retrieved on 2012-06-23.

- Orange British Academy Film Awards. BAFTA. Retrieved on 2012-06-23.

- JOE SIMPSON: Touching the Void Archived 2011-01-11 at the Wayback Machine. Wolfman Productions. Retrieved on 2012-06-23.

- "Touching the Void to be brought to the stage in Edinburgh". scotsman.com. The Scotsman. 8 November 2017. Retrieved 20 September 2018.

- "Bristol Old Vic announces Touching the Void and The Cherry Orchard adaptations for 2018". whatsonstage.com. Whats On Stage. 8 November 2017. Retrieved 20 September 2018.

- "Touching the Void". bristololdvic.org.uk. Bristol Old Vic. 8 September 2018. Retrieved 23 September 2018.

- "New Tour Dates Announced For Tom Morris' Production Of TOUCHING THE VOID". broadwayworld.com. Broadway World. 18 September 2018. Retrieved 7 October 2018.

References

- Simpson, Joe (1988). Touching the Void. Perennial. p. 218. ISBN 978-0-06-073055-0.

- Touching the Void – 25th Anniversary ebook Edition Interview