Timeline of typhoid fever

This is a Timeline of typhoid fever, describing major events such as scientific/medical developments and notable epidemics.

Big picture

| Year/period | Key developments |

|---|---|

| 1890s | Several different researchers work on the idea of protection against typhoid fever at the same time.[1] |

| 20th Century | Throughout the century, the incidence of typhoid fever steadily declines, due to the introduction of vaccinations and improvements in public sanitation and hygiene. In particular, the water chlorination would significantly reduce the incidence of typhoid fever among the population.[2] |

| 1980s | Antibiotics like fluoroquinolones such as ciprofloxacin and ofloxacin become widespread especially in countries where multidrug resistance is a problem.[3] |

| Recent years | According to the World Health Organization, there are about 22 million cases of typhoid fever and 200,000 deaths annually.[4][1][3] |

Full timeline

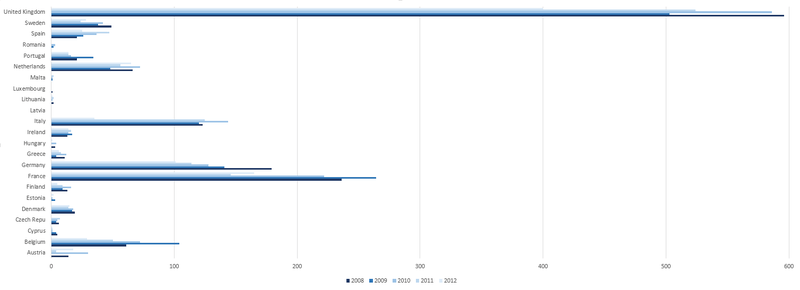

Number of confirmed typhoid-paratyphoid fever reported cases in European countries in the period 2008–2012, illustrating the proportion among countries. Highest rates were given in Northwestern Europe and Scandinavia.[5]

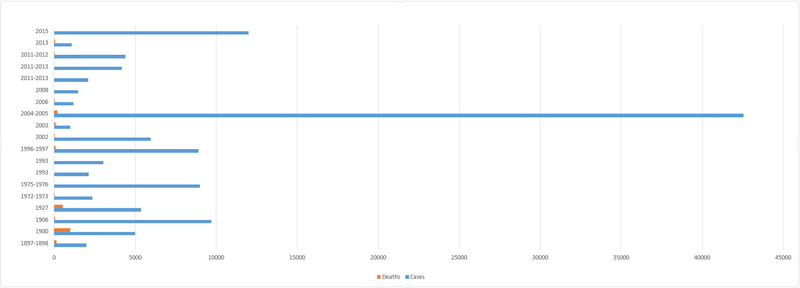

Number of cases and deaths due to typhoid fever, by outbreak. Higher death rates are noticeable in earlier outbreaks.[6]

| Year or period | Type of event | Event | Geographical location |

|---|---|---|---|

| 460–377 BC | Scientific development | Greek physician Hippocrates describes clinical features resembling typhoid fever.[7] | Greece |

| 430–424 BC | Epidemic | Typhoid fever epidemic ravages Athens, whiping out about one third of its population.[8] | Greece |

| 1643 | Scientific development | English physician Thomas Willis describes typhoid fever in his Treatise on Fevers.[7][9] | United Kingdom |

| 1826 | Scientific development | French worker Pierre Bretonneau describes the constancy of intestinal lessions and attempts to clarify the pathology of typhoid fever.[7] | France |

| 1829 | Medical development | French physician Pierre Charles Alexander Louis becomes the first to use the word Thyphoide.[7] | |

| 1836 | Medical development | William Wood Gerhard differentiates typhus and typhoid as two distinct clinical entities and establishes the differential clinical and pathological features of both diseases.[7] | |

| 1838 | Medical development | English epidemiologist William Budd, while treating an outbreak of typhoid, notes that the poison (as he then calls it) is present in the excretions of the infected and could be transmitted to healthy people through contaminated water consumption. Upon realizing this association, Budd suggests isolating excrement to help control future outbreaks.[2][10] | United Kingdom |

| 1842 | Scientific development | John Goodsir describes differences in pathological lessons between typhus and typhoid fever.[7] | United Kingdom (Edinburgh) |

| 1861–1865 | Epidemic | About 80,000 soldiers die as a result of typhoid fever or dysentery in the American Civil War.[2] | United States |

| 1874 | Scientific development | Leydon links typhoid to symptoms in the nervous system. For some time typhoid fever would be described as brain fever and nervous fever.[7] | |

| 1880 | Scientific development | Kart Joseph Ebert first demonstrates the presence of bacterium salmonella typhi in the histologic sections of spleen and mesenteric glands of patients who had died of typhoid fever.[7][9] | |

| 1885 | Scientific development | German bacteriologists Richard Pfeiffer first discovers the presence of typhus–causing bacterium salmonella typhi in stools.[7] | Germany |

| 1886 | Scientific development | German bacteriologist Ferdinand Adolph Hueppe demonstrates the presence of typhus–causing bacterium salmonella typhi in urine.[7] | |

| 1894 | Scientific development | Austrian pathologist Hans Chiari successfully cultures typhoid bacillus in gallblader.[7] | |

| 1896 | Scientific development | German bacteriologists Richard Pfeiffer and Wilhelm Kolle demonstrate that inoculation with killed typhoid bacteria results in human immunity against typhoid fever.[1] | Germany |

| 1896 | Scientific development | French physicians Émile Achard and Raoul Bensaude isolate bacterium salmonella paratyphi B and are the first to use the term paratyphoid fever.[7] | France |

| 1896 | Scientific development | George Widal develops a typhoid fever diagnostic using the serum of patients who are recovering from the disease.[9][7] | |

| 1897 | Medical development | British bacteriologist Almroth Wright develops a vaccine prepared from killed typhoid bacilli as a preventive of typhoid.[1] | United Kingdom |

| 1897–1898 | Epidemic | Typhoid fever epidemic breaks out in Maidstone, England, involving 2,000 people and claiming 143 lives.[6] | United Kingdom |

| 1899–1902 | Epidemic | Second Boer War. Typhoid fever is estimated to be the cause of twice as many deaths as from weapons.[7] In an outbreak in 1900 in Bloemfontein, 5,000 cases and 143 deaths are calculated.[6] | South Africa |

| 1906 | Epidemic | Typhoid fever epidemic breaks out in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, involving 9,712 people and claiming 63 lives.[6] | United States |

| 1907–1915 | Infection | Irish immigrant Mary Mallon (better known as Typhoid Mary) becomes the first person in the United States identified as an asymptomatic carrier of the pathogen associated with typhoid fever. Presumed to have infected 51 people (three of whom die), Mary Mallon would be forcibly isolated for quarantine purposes twice in her life, once in 1907 and again in 1915. The second time she would not be released, dying in isolation at the age of 69.[2][11][9] | United States |

| 1909 | Medical development | United States Army physician Frederick F. Russell develops a perfected typhoid fever vaccine, and the first in the United States. Russell would begin immunizing volunteers in the army, and after demonstrating its effectiveness, the army would make would make typhoid immunization compulsory, reducing the rate from 243 to 4.41 in three years.[12][1][13] | United States |

| 1914 | Campaign | Typhoid vaccination moves beyond military forces and are released for the general public.[1] | United States |

| 1927 | Epidemic | Typhoid fever epidemic breaks out in Montreal. 5,353 cases and 538 deaths are recorded. Milk is found to be the source of the outbreak.[6] | Canada |

| 1948 | Medical development | American medical researcher Theodore Woodward and colleagues publish the first report on the use of Chloramphenicol for the treatment of typhoid fever. Chloroamphenicol would revolutionize the field by reducing both morbidity and mortality.[3][14][9][7] | |

| 1953 | Scientific development | Antibacterial agent furazolidone is reported effective in vitro for treating common species of salmonella. The drug would later be used for the treatment against typhoid fever.[15][7] | |

| 1961 | Medical development | Ampicillin is introduced for the treatment against typhoid fever.[16][7] | |

| 1969 | Medical development | Antibiotic agent Trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole (also known as co-trimoxazole) is introduced. The drug would prove to be effective in the treatment against typhoid fever.[17][7] | |

| 1972 | Medical development | Researchers from Beecham Group develop antibiotic amoxicillin. It would prove to be very effective against typhoid fever, reducing the risk of the carrier state. Amoxicilin is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines.[7][18] | |

| 1972–1973 | Epidemic | Typhoid fever epidemic breaks out in Mexico City, involving 9,000 cases. Contamination of a municipal water supply is found to be the source of the outbreak.[6] | Mexico |

| 1975–1976 | Epidemic | Typhoid fever epidemic breaks out in Maharashtra. 2,343 cases and 39 deaths are calculated.[6] | Mexico |

| 1986 | Medical development | Researchers at the United States National Institutes of Health develop an injectable subunit vaccine Vi-polysaccharide vaccine (sold as Typhim Vi by Sanofi Pasteur and Typherix by GlaxoSmithKline), for immunization against typhoid fever.[3] | United States |

| 1993 | Epidemic | Typhoid fever epidemic breaks out in Mpumalanga, South Africa. Contamination of water supplies is associated. Over 1000 cases are reported.[19] | South Africa |

| 1997 | Epidemic | Quinolone-resistant typhoid breaks out in Tajikistan, involving 8,000 people and claiming 150 lives.[20] | Tajikistan |

| 2001 | Epidemic | Typhoid fever epidemic breaks out in vaccinated members of the French Armed Forces in Ivory Coast.[21] | Ivory Coast |

| 2007 | Medical development | Live attenuated vaccine (DV-STM-07) is developed for immunization against typhoid fever.[3] | |

| 2012 | Epidemic | Typhoid fever epidemic breaks out in Harare, Zimbabwe. Contaminated water sources are associated. As of 2017, the epidemic is still ongoing, with over 4,000 cases diagnosed to date.[19] | Zimbabwe |

See also

References

- "Typhoid Fever Symptoms and Causative Agent". historyofvaccines.org. Retrieved 10 February 2017.

- "Typhoid Fever History". news-medical.net. Retrieved 11 February 2017.

- Marathe, Sandhya A.; Lahiri, Amit; Devi Negi, Vidya; Chakravortty, Dipshikha (2012). "Typhoid fever & vaccine development: a partially answered question". The Indian Journal of Medical Research. 135 (2): 161–169. PMC 3336846. PMID 22446857.

- "Typhoid Fever Quick Overview". emedicinehealth.com. Retrieved 10 February 2017.

- "Annual epidemiological report 2014" (PDF). europa.eu. Retrieved 4 March 2017.

- Berger, Stephen (2017-01-20). Typhoid and Enteric Fever: Global Status: 2017 edition. ISBN 9781498816878. Retrieved 4 March 2017.

- Khosla, S.N. (2008). Typhoid Fever – Its Cause, Transmission And Prevention. ISBN 9788126909124. Retrieved 3 March 2017.

- "Top 10 epidemic diseases that were common in ancient world". ancienthistorylists.com. Retrieved 3 March 2017.

- Emmeluth, Donald; Alcamo, Edward (2009). Typhoid Fever. ISBN 9781438101774. Retrieved 3 March 2017.

- Moorhead, Robert (2002). "William Budd and typhoid fever". Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. 95 (11): 561–564. doi:10.1258/jrsm.95.11.561. PMC 1279260. PMID 12411628.

- "'Typhoid Mary' Dies of a Stroke at 68 – Carrier of Disease, Blamed for 51 Cases and 3 Deaths, but She Was Held Immune – Services This Morning – Epidemic Is Traced". Archived from the original on 5 June 2011. Retrieved 11 February 2017.CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link)

- Byerly, Carol R (2005-04-05). Fever of War: The Influenza Epidemic in the U.S. Army during World War I. ISBN 9780814789636. Retrieved 4 March 2017.

- Cirillo, Vincent J. (2004). Bullets and Bacilli: The Spanish–American War and Military Medicine. ISBN 9780813533391. Retrieved 4 March 2017.

- Bitar, R; Tarpley, J. (1985). "Intestinal perforation in typhoid fever: a historical and state-of-the-art review". Reviews of Infectious Diseases. 7 (2): 257–71. doi:10.1093/clinids/7.2.257. PMID 3890098.

- Bierer, Bert W.; Vickers, C. L. (1960). "Nitrofuran Medication for Experimental Salmonella typhimurium Infection in Poults". Avian Diseases. 4 (1): 22–37. doi:10.2307/1587464. JSTOR 1587464.

- Simon, Harold J.; Miller, Raymond C. (1966). "Ampicillin in the Treatment of Chronic Typhoid Carriers — Report on Fifteen Treated Cases and a Review of the Literature". N Engl J Med. 274: 807–15. doi:10.1056/NEJM196604142741501. PMID 5908876.

- LACEY, R. W. "Do Sulphonamide-Trimethoprim Combinations Select Less Resistance to Trimethoprim Than The Use of Trimethoprim Alone?" (PDF). The Journal of Medical Microbiology. Retrieved 3 March 2017.

- "Amoxicillin". emedexpert.com. Retrieved 3 March 2017.

- "Typhoid -caused by Salmonella Typhi-Frequently Asked Questions". South African National Institute for Communicable Diseases. Retrieved 4 March 2017.

- "Salmonella typhi (Typhoid Fever) and S. paratyphi (Paratyphoid Fever)". antimicrobe.org. Retrieved 4 March 2017.

- Michel, Rémy; Garnotel, Eric; Spiegel, André; Morillon, Marc; Saliou, Pierre; Boutin, Jean-Paul. "Outbreak of Typhoid Fever in Vaccinated Members of the French Armed Forces in the Ivory Coast". European Journal of Epidemiology.

This article is issued from Wikipedia. The text is licensed under Creative Commons - Attribution - Sharealike. Additional terms may apply for the media files.