Timeline of healthcare in Ethiopia

This is a timeline of healthcare in Ethiopia, focusing especially on modern science-based medicine healthcare. Major events such as policies and organizations are described.

Big picture

| Year/period | Key developments |

|---|---|

| Prior to 1896 | Local traditional African medicine is present in Ethiopia for most of its history. |

| 1896–onward | Western medicine is consolidated after first hospital is built by Europeans.[1] |

| 1948–onward | The Ministry of Health is established.[1] |

| Present | Today, the major health problems of Ethiopia remain largely preventable communicable diseases and nutritional disorders. The rate of morbidity and mortality remain high and the health status is relatively poor. Physician brain drain is an actual major issue.[1] |

Full timeline

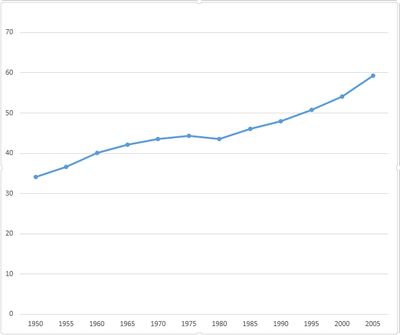

Evolution of life expectancy in Ethiopia for the period 1950–2005.[2]

| Year/period | Type of event | Event | Location |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1896 | Organization | The Russian Red Cross builds the first hospital in Ethiopia.[1] | |

| 1939 | Report | First case of onchocerciasis in Ethiopia is reported.[3] | |

| 1942 | Report | First case of visceral leishmaniasis in Ethiopia is identified.[3] | |

| 1948 | Organization | The Ministry of Health is established.[1] | |

| 1954 | Organization | University of Gondar College of Medicine and Health Sciences is founded.[4] | Gondar |

| 1956 | Campaign | An organized leprosy control program is established in Ethiopia within the Ministry of Health.[3] | |

| 1964 | Policy | Pharmacy Regulation No.288/1964 is introduced. This legislation forms the legal basis for official establishment of drug regulation in Ethiopia, enabling the regulation of the practice of pharmacists, druggists and pharmacy technicians; manufacturing, distribution, and sale of medicines.[5] | |

| 1969 | Report | First case of dracunculiasis is reported in Ethiopia.[3] | |

| 1983 | Campaign | Multiple Drug Therapy (MDT) is massively implemented in Ethiopia, leading to relatively rapid reduction in prevalence of leprosy.[3] | |

| 1988–1989 | Report | The national schistosomiasis survey reports an overall prevalence of 25% over the total population in Ethiopia.[3] | |

| 1989 | Organization | Ethiopiaid is established as a registered charity that generates public funding for local charity partners in Ethiopia.[6] | |

| 1989 | Organization | ActionAid Ethiopia (AAI-E) is founded as a charity organization. It assists in HIV/AIDS and primary health care (PHC), food security and emergency responses, among other interventions.[7] | |

| 1993 | Campaign | The Ethiopian Ministry of Health establishes the National Dracunculiasis Eradication Program, and launches a village-by-village nationwide search during which 1,120 cases are found in 99 villages in the southwest part of the country.[3] | |

| 1994 | Campaign | Leprosy is combined with tuberculosis under a joint control program.[3] | |

| 1996 | Organization | Awassa Health Science College is founded.[8] | Hawassa |

| 1998 | Campaign | Community-based lymphoedema management for podoconiosis is started.[3] | Wolayita Zone |

| 1999 | Campaign | The first national plan to fight onchocerciasis is developed.[3] | |

| 1999 | Policy | Drug Administration and Control Proclamation No.176/1999” is introduced as new regulation, repealing most parts of the regulation 288/1964. The new law establishes an independent Drug Administration and Control Authority (DACA) with further mandate of setting standards of competence for licensing institutions/facilities.[5] | |

| 1999 | Achievement | Ethiopia reaches the leprosy elimination target of 1 case/10,000 population.[3] | |

| 2000 | Campaign | Ethiopia implements the WHO-approved SAFE strategy for trachoma control: surgeries, antibiotics, face and hand washing and environmental hygiene.[3] | |

| 2000 | Organization | The National Onchocerciasis Task Force is established by Ethiopia's Ministry of Health. Its mission encompasses mobilizing and educating onchocerciasis-endemic communities; coordinating Mectizan tablet procurement (donated by Merck) and distribution; and coordinating all partners in the program.[3] | |

| 2001 | Organization | Project Harar is established as a charity organization working in Ethiopia to help children affected by facial disfigurements.[9] | |

| 2004 | Campaign | The Enhanced Outreach Strategy (EOS) program is launched under the mission of deworming 2– to 5-year-old children every six months. The strategy is implemented in every district in the country except Addis Ababa. By 2009 the program has reached more than 11 million children in 624 districts.[3] | |

| 2005–2006 | Report | Survey conducted suggests that Ethiopia is the most trachoma-affected country in the world.[3] | |

| 2006 | Report | The total number of physicians in the public sector in Ethiopia reaches an all-time low of 638.[1] | |

| 2006 | Campaign | A leishmaniasis control program that includes mandatory notification is established.[3] | |

| 2006 | Campaign | Ethiopia's Reproductive Health Strategy (2006–2015) is launched. It identifies six priority areas: social and cultural determinants of women's reproductive health; fertility and family planning; maternal and newborn health; HIV/AIDS; reproductive health of young people; and reproductive organ cancers.[10] | |

| 2009 | Campaign | The Ethiopian Ministry of Health launches a lymphatic filariasis elimination program. The program reaches 84% of its target by providing annual Mass drug administration of a single dose of ivermectin and albendazole to a target of almost 100,000 people.[3] | Gambela Region |

| 2010 | Campaign | More than 14.7 million people receive azithromycin through the Carter Center, using what is known as the MalTra-Week Strategy (combining malaria case detection and treatment with mass azithromycin distribution).[3] | |

| 2010 | Policy | The Ethiopian Drug Administration and Control Authority DACA is restructured as Food, Medicine and Health Care Administration and Control Authority (EFMHACA) by Proclamation No. 661/2009, bearing additional responsibilities like regulation of food, health care personnel and settings.[5] | |

| 2011 | Report | Individual latrine coverage (ownership and utilization) reaches 45% for rural households in Ethiopia.[3] | |

| 2013 | Policy | Ethiopia includes podoconiosis in its national neglected tropical diseases (NTD) master plan, given that the greatest burden of podoconiosis globally is assumed to occur in Ethiopia.[11] | |

| 2016 | Report | Life expectancy in the Ethiopia is estimated at 58 years, being ranked 203rd out of 228 political subdivisions.[12] | |

References

- "Ethiopia's Physician Brain-Drain Problem; What to Do?". Retrieved 14 October 2016.

- "Life Expectancy". Retrieved 18 November 2016.

- Deribe, K; Meribo, K; Gebre, T; Hailu, A; Ali, A; Aseffa, A; Davey, G (2012). "The burden of neglected tropical diseases in Ethiopia, and opportunities for integrated control and elimination". Parasit Vectors. 5: 240. doi:10.1186/1756-3305-5-240. PMC 3551690. PMID 23095679.

- "Training for the future: Building sustainable health systems, one doctor at a time". Retrieved 14 October 2016.

- Suleman, S; Woliyi, A; Woldemichael, K; Tushune, K; Duchateau, L; Degroote, A; Vancauwenberghe, R; Bracke, N; De Spiegeleer, B (2016). "Pharmaceutical Regulatory Framework in Ethiopia: A Critical Evaluation of Its Legal Basis and Implementation". Ethiop J Health Sci. 26: 259–76. doi:10.4314/ejhs.v26i3.9. PMC 4913194. PMID 27358547.

- "Ethiopiaid". Retrieved 20 November 2016.

- "ActionAid". Retrieved 14 October 2016.

- "ETIOLOGY OF BACTERIAL MENINGITIS IN ETHIOPIA, 2007 – 2011: A RETROSPECTIVE STUDY" (PDF). Retrieved 14 October 2016.

- "Project Harar". Retrieved 14 October 2016.

- "Ethiopia's Reproductive Health Strategy" (PDF). Retrieved 17 October 2016.

- Deribe, K; Cano, J; Newport, MJ; Golding, N; Pullan, RL; Sime, H; Gebretsadik, A; Assefa, A; Kebede, A; Hailu, A; Rebollo, MP; Shafi, O; Bockarie, MJ; Aseffa, A; Hay, SI; Reithinger, R; Enquselassie, F; Davey, G; Brooker, SJ (2015). "Mapping and Modelling the Geographical Distribution and Environmental Limits of Podoconiosis in Ethiopia". PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 9: e0003946. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0003946. PMC 4519246. PMID 26222887.

- "Life Expectancy". Retrieved 17 October 2016.

This article is issued from Wikipedia. The text is licensed under Creative Commons - Attribution - Sharealike. Additional terms may apply for the media files.