Timeline of British diplomatic history

This timeline covers the main points of British (and English) foreign policy from 1485 to the early 21st century.

16th century

- Henry VII becomes king (1485–1509), founding the Tudor dynasty and ending the long civil war called "Wars of the Roses". His foreign policy involves an alliance with Spain, cemented by the marriage of his son Arthur to the Spanish princess Catherine of Aragon. However, after 5 months, Arthur dies at the age of 15. Henry VII reverses the Plantagenet policy of acquiring more French territory; he generally pursues a more defensive, Anglo-centric policy[1]

- 1485–1509: The king promotes the woolen trade with Netherlands; helps English merchants compete with the Hanseatic League; sends John Cabot to explore the New World (1497); launches the Royal Navy

- 1489–91: England sends three expensive military expeditions to keep Brittany out of French control, but fails.

- 1502: Treaty of "perpetual peace" signed with Scotland. The marriage of King James IV of Scotland to Margaret Tudor will eventually lead to the Stuart succession to the English throne.

- 1509–47 Henry VIII becomes king; he revives the old claim to the French throne but France is now a more powerful country and the English control is limited to Calais

- 1511–16: War of the League of Cambrai allied with Spain against France; on losing side.

- 1513 English defeat & kill King James IV of Scotland at Battle of Flodden Field; he was allied with France.

- 1520: 7 June: Henry VIII meets with Francis I of France near Calais at the extravagant "Field of the Cloth of Gold"; no alliance results.[2]

- 1521–26: Italian War of 1521–26 allied with Spain against France; on winning side

- 1525: Queen Catherine does not produce the male heir the king demands, so he decides on a divorce (which angers Spain).

- 1526–30 War of the League of Cognac, allied with France; Spain wins

- 1529 Henry VIII severs ties with Rome because of marriage issue; and declares himself head of the English church; Catholic Spain supports the Pope.

- 1533: Pope Clement VII excommunicates Henry and annuls his divorce from Catharine

- 1542: War with Scotland. James V defeated at the Battle of Solway Moss

- 1551–59: Italian War of 1551–59; allied with Spain against France; on winning side

- 1553–58: Mary I is queen; she promotes Catholicism and an alliance with Catholic Spain[3]

- 1554: Mary I marries Prince Philip of Spain, the king of Spain (1556–98). "The Spanish marriage" was unpopular even though Philip was to have little or no power. However he pushes Mary into alliance with Spain in a war with France that resulted in the loss of Calais in 1558

- 1558–1603 Elizabeth I as Queen;[4] Sir William Cecil (baron Burleigh, 1571) serves as chief advisor; they avoid European wars.[5] Her spymaster Sir Francis Walsingham thwarts numerous plots supported by Spain or France to assassinate the Queen. The long-term English goal becomes a united and Protestant British Isles, through conquest of Ireland and alliance with Scotland. Defence is the mission of a strengthened Royal Navy.[6]

- 1573: Convention of Nymegen a treaty with Spain promising to end support for raids on Spanish shipping by English privateers such as Drake and Hawkins.[7]

- 1580–1620s – English merchants form the Levant Company to promote trade with Ottoman Empire; they build a presence in Istanbul and trade grew as the Turks bought arms and cloth.[8]

- 1585: By the Treaty of Nonsuch with the Netherlands, England supported the Dutch revolt against Spain with soldiers and money. Spain decides this means war and prepares an armada to invade England.[9]

- 1585–1604: Anglo-Spanish War (1585–1604) was an undeclared intermittent naval conflict; English strategy focused on raids on ports such as Cadiz, and seizure of Spanish merchant ships because it was much cheaper than land forces—using privateers ("Sea Dogs") who turned a large profit when they captured prizes—let the naval warfare pay for itself.[10]

- 1588: Massive Spanish invasion thwarted by destruction of Spanish Armada; it is celebrated for centuries as a decisive defeat for England's Catholic enemy.[11]

17th century

- 1603–1714 was the Stuart period[12]

- 1603: James VI of Scotland crowned King of England (as James I of England (1603–25), marking a permanent union of the two thrones

- 1604: King James achieves peace with Spain in Treaty of London; both sides will no longer support rebellions[13]

After years of conflict, Spain and England sign the Treaty of London, 29 August 1604. (painting)

- 1613: James marries his daughter Elizabeth to Frederick V, Elector Palatine, leader of the Protestant Union of German princes. James associates his kingdoms with the anti-Habsburg forces with this marriage.[14]

- 1613–20: Netherlands becomes England's major rival in trade, fishing, and whaling. The Dutch form alliances with Sweden and the Hanseatic League; England counters with an alliance with Denmark

- 1610s: English involvement with Russia; strengthens the Muscovy Company, which has a monopoly on trade with Russia. In 1613 it obtains a monopoly on whaling in Spitsbergen. A Russian embassy comes to London in 1613.[15]

- 1613: The English captain John Saris arrives at Hirado, Japan, with the intent of establishing a trading factory. He met with Tokugawa Ieyasu. However, during the ten-year activity of the company between 1613 and 1623, only four English ships brought cargoes directly from London to Japan.[16]

- 1623. The Amboyna massacre occurs in Japan. England closes its commercial base at Hirado. The relationship ends for more than two centuries.[17]

- 1624–25: The king turns to France after negotiations with Spain for a marriage to the infanta had stalled. With religion closely tied to politics, France demanded an end to the persecution of Catholics in England as a condition for the marriage. The negotiations fail.

- 1627–28: English attempt to aid besieged Huguenots in the Siege of La Rochelle, but fail. This is the only major English contribution to the Thirty Years' War.[18]

- 1639–40: Bishops' Wars with Scotland[19]

- 1642: English Civil War begins see Timeline of the English Civil War and Wars of the Three Kingdoms

- 1652–54: First Anglo-Dutch War[20]

- 1654–60: Anglo-Spanish War (1654–60)[21]

- 1657: Alliance with France signed against Spain.

- 1661: King Louis XIV of France begins his personal reign, taking control of the state. Louis as the leader of the most powerful nation in western Europe begins a policy of aggressively asserting French interests and expanding the borders of France. Until his death in 1715, France's hegemonic aspirations are the principle driving drive in diplomacy in western Europe.[22]

- 1665–67: Second Anglo-Dutch War.[23]

- 1665: Charles II of Spain begins his reign. The last of the Spanish Habsburgs. As Carlos is childless with no Spanish relatives and as he is very sickly, his expected death raises the highly controversial issue of succession to the Spanish throne. The main candidates for the Spanish succession are the French Bourbons and the Austrian Habsburgs.

- 1667: War of Devolution. France attacks Spain and occupies much of the Spanish Netherlands and the Franche-Comté. The prospect that France might annexe the entire Spanish Netherlands is viewed as a threat in London.

- 1667: Treaty of Breda ends of the Dutch war. It is a major turning point after which mercantilism ceased to dominate Anglo-Dutch relations.[24]

- 1668: Triple Alliance of England, Sweden and the United Provinces formed to oppose France. Spain is defeated, but the threat that the Triple Alliance might intervene on Spain's side forces the French to make peace. Louis annexes less Spanish territory than what he planned on. The French decide that the Dutch will be their next target, and accordingly Louis seeks to break up the Triple Alliance by bidding for English and Swedish friendship.[25]

- 1670: Treaty of Dover. Secret Anglo-French alliance formed. In exchange for French subsidies and a promise to send an army to England should another civil war break out between king and Parliament, Charles II agrees to convert to Catholicism and to fight with France against the Dutch. Until the Glorious Revolution of 1688, England was a close ally of France.[26]

- 1672–74: Third Anglo-Dutch War begins.

- 1673: Revelation of the pro-Catholic Secret Treaty of Dover causes public backlash against the war and the Crown.

- 1688–89: William of Orange invades from the Netherlands as King James II flees; becomes William III; called the Glorious Revolution[27] Louis continues to recognise the deposed James II/VII, who takes refuge in France and is promoted by France as the legitimate king of England, a policy known as Jacobitism. French support was a major factor in British diplomacy until the mid-18th century. William allows James and his family to escape after being captured as the threat of a Jacobite restoration supported by France forces gives those who supported the Glorious Revolution a vested interest in ensuring that England is not defeated by France, and James is restored. Parliament accordingly votes for all the war taxes William requests. From William's viewpoint, James is more useful as king in exile in France than as a prisoner in the Tower of London.

- 12 May 1689: Reflecting the changed foreign policy orientation caused by the Glorious Revolution, William has England join the anti-French League of Augsburg and declare war on France (as a stadtholder of the United Provinces, William had already declared war on France on 26 November 1688.[28]).

- 1689–97 War of the Grand Alliance with France; also called "Nine Years War" or "War of the League of Augsburg" or " King William's War"[29]

- 1697–98: During the Grand Embassy of Peter I the Russian tsar visited England for three months; improved relations and learned the best new technology especially regarding ships and navigation.[30]

- 11 October 1698: Treaty signed between France, England, the Dutch Republic and the Holy Roman Emperor proposing three-fold division of Spain after the soon to be expected death of Carlos II between the French Bourbons, the Austrian Habsburgs and the Bavarian Wittelsbachs. The largest portion of the Spanish realms are to go to Josef Ferdinand of Bavaria. The treaty is undermined when Josef Ferdinand dies in 1699.[31]

1700–1789

- 25 March 1700: Another partition treaty signed between France, England and the United Provinces concerning the Spanish succession with the Bourbons receiving Naples, Sicily, Milan and the Spanish fortresses in Tuscany and the rest of the Spanish realms going to the Austrian Habsburgs.[32] The proposed partition breaks down when the Holy Roman Emperor Leopold I insists that the entire Spanish empire go to his son Archduke Karl.[33]

- 1 November 1700: Carlos II of Spain dies, leaves the entire Spanish succession to Duke Philippe of Anjou, the second son of the Dauphin who becomes King Felipe V of Spain.[34] King Louis XIV of France issues letters patent explicitly stating that Philip is in the line of succession to the French throne, creates the possibility of France and Spain uniting to become a Catholic super-state that would dominate Europe.[35] Additionally, Louis takes the opportunity to remind the world that he recognizes the Catholic the Old Pretender as King James III of England/James VIII of Scotland.[36] Louis's actions which are seen as very threatening to England and all but guarantee a war.

- 1701–15: War of the Spanish Succession against France and Spain, in "Grand Alliance" with Austria, Prussia and the Dutch Republic. Britain fights in support of the Habsburg Archduke Karl of Austria's claim to the Spanish throne.[37]

- 15 May 1702: War declared against France.[38]

- 1704: Gibraltar captured on 4 August by the combined Dutch and British fleets; becomes British naval bastion into the 21st century.[39]

- 1704: An English and Dutch army under John Churchill, 1st Duke of Marlborough defeats the army of Louis XIV of France at Battle of Blenheim in Bavaria.[40]

- 1706–07: The Treaty of Union merges Scotland into Britain; the Kingdom of Great Britain comes into being on 1 May 1707.[41] Scots play an increasingly major role in the British Empire.

- 1708: Louis XIV sues for peace. The French agree to the Allied demand that the Archduke Karl become King of Spain, but the talks break down over the Allied demand that Louis send an army to Spain to depose his grandson Philip.[42]

- 12 June 1709: Louis XIV says he was willing to concede to the Allied demands over the Spanish succession, but rejected the demand that he send an army to Spain to depose as an insult to French national honour.[43] French win the moral high ground as many people in France, Britain and elsewhere see the demand that Louis depose Philip to be outrageous. New French commander Marshal Claude Louis Hector de Villars appointed to oppose Marlborough, proves to be the ablest French general of the war.[44]

- 11 September 1709 -Bloody Battle of Malplaquet. Marlborough victorious over Villars, but Malplaquet is a Pyrrhic victory with the British losing twice what the French suffered.[45] Public opinion in Britain turns against the war after Malplaquet. Vigorous attacks by the Tory opposition on the Whig government for the war, its support of "Butcher Marlborough" and widespread corruption in regards to war contracts.

- 2 October-16 November 1710: General election results in a landslide victory for the Tories on a peace platform.

- 17 April 1711: Holy Roman Emperor Josef I dies, and his younger brother the Archduke Karl is elected his successor.[46] Queen Anne and her ministers see no point to continuing the war as allowing Karl to become King of Spain would create a Habsburg super-state which would be just as much a potential danger as a Bourbon super-state.[47]

- 8 October 1711 -British and French governments sign the "London Preliminaries" to a peace treaty.[48]

- 29 January 1712 -Peace conference opens in Utrecht.[49]

- May 1712: Queen Anne issues "Restraining Orders" that forbid the British Army to fight the French unless attacked.[50] Britain effectively withdraws the war.

- 11, April 1713: Treaty of Utrecht, ends War of the Spanish Succession and gives Britain territorial gains, especially Gibraltar, Acadia. Newfoundland, and the land surrounding Hudson Bay. The lower Great Lakes-Ohio area became a free trade zone.[51] Philip stays on the Spanish throne, but is excluded from the French succession. The Spanish Netherlands becomes the Austrian Netherlands. Having strategically important Low Countries under Bourbon control is seen as a threat to Britain.

- 1714: The Elector of Hanover becomes king of Great Britain as George I; start of the Hanoverian dynasty.[52]

- 1714–1717, 1731–1730: Charles Townshend, 2nd Viscount Townshend largely sets foreign policy as Secretary of State for the Northern Department; after 1726 displaced by Robert Walpole

- 1715: Death of King Louis XIV in France. Regency of Duke of Orleans pursues policy of peace and friendship towards Britain.

- 1718–1720: War of the Quadruple Alliance against Spain.

- 1719: Failed Spanish invasion in support of Jacobites; Spanish fleet dispersed by storms. Spanish land in Scotland but are defeated at Battle of Glen Shiel.

- 1719: King George I orders Royal Navy into action against Sweden as part of the Great Northern War. The use of British power to further Hanoverian goals is deeply unpopular with public opinion.

- 1721: Peace signed with Sweden.

- 1722–1742: Sir Robert Walpole as (in effect) the Prime Minister. He takes charge of foreign policy around 1726; Britain pursues policy of peace and non-intervention in European conflicts.[53]

- 1739–1742: War of Jenkins' Ear begins with Spain over smuggling and trade. Public opinion demanded it over Walpole's opposition; he fell from power. The war was inconclusive and expensive; it hurt legitimate trade. It merged into the War of the Austrian Succession in 1740.[54]

- 1740–1748: War of the Austrian Succession begins, which merges into war with Spain. Britain fights against France and Spain in support of Austria and its new Queen Maria Theresa.[55][56]

- 1744: large-scale French invasion attempt on southern England with Charles Edward Stuart stopped by storms, France declares war.

- 1746: 16 April. Battle of Culloden in Scotland. Final victory of Hanoverians over Jacobites supported by France

- 1748: Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle (1748) ends War of Austrian Succession. The war was indecisive and the "peace" was an armed truce.

- 1754: Undeclared war between France and Britain begins in North America, known as the French and Indian War in the United States. Fighting breaks out in the Ohio river valley between Franco-Indian and British and colonial American forces.[57]

- 1756: Westminster Convention signed between Britain and Prussia. Part of the Diplomatic Revolution that saw Britain drop long-standing ally Austria in favour of Prussia.[58]

- 1756–63 Seven Years' War, Britain, Prussia, and Hanover against France, Austria, the Russian Empire, Sweden, and Saxony. Major battles in Europe and North America; the East India Company also in involved in the Third Carnatic War (1756–1763) in India. Britain victorious and takes control of all of Canada; France seeks revenge.[59]

- 1775–83: American Revolutionary War as Thirteen Colonies revolt; Britain has no major allies.[60]

- 1776: Royal governors expelled from Thirteen United Colonies; they vote independence as the United States of America on 2 July; Declaration of Independence adopted on 4 July; France ships arms to Americans

- 1777: France decides to recognise America in December after British invasion army from Canada surrenders to Americans at the Battle of Saratoga in New York; French goal is revenge from defeat in 1763[61]

- 1778: Treaty of Allies. US and France form military alliance against Britain. The military and naval strengths of the two sides of the war are now about equal.

- 1778: Carlisle Peace Commission offers Americans all the terms they sought in 1775, but not independence; rejected

- 1779: Spain enters the war as an ally of France (but not of US)

- 1780: Russian Empire proclaims "armed neutrality" which helps France & the US and hurts the British cause

- 1780–81: Russia and Austria propose peace terms; rejected by US

- 1781: At peace negotiations in Paris, Congress insists on independence; all else is negotiable; British policy is to help US at expense of France

- 1783: Treaty of Paris ends Revolutionary War; British give generous terms to US with boundaries as British North America on north, Mississippi River on west, Florida on south. Britain gives East and West Florida to Spain[62]

- 1784: Britain allows trade with America but forbid some American food exports to West Indies; British exports to America reach £3.7 million, imports only £750,000

- 1784: Pitt's India Act re-organised the British East India Company to minimise corruption; it centralised British rule by increasing the power of the Governor-General

- 1785: Congress appoints John Adams as minister to Court of St James's

1789–1815

- 1789–1815: The French Revolution polarized British political opinion in the 1790s, with conservatives outraged at killing of the king, the expulsion of the nobles, and the Reign of Terror. Britain was at war against France almost continuously from 1793 until the final defeat of Napoleon in 1815. Its strategy was to mobilize and fund the coalition against France. William Pitt the Younger was the dominant leader until his death in 1806. At home, conservatives castigated every radical opinion as "Jacobin" (in reference to the leaders of the Terror), warning that radicalism threatened an upheaval of British society.[63]

- 1791–92: Government rejects intervention in French Revolution. Reasons are based on realism not ideology and are to avoid French attacks on the Austrian Netherlands; to not worsen the fragile status of King Louis XVI; and to prevent formation of a strong Continental league.[64]

- 1792–1799: French Revolutionary Wars[65]

- 1792–97: War of the First Coalition: Prussia and Austria joined after 1793 by Britain, Spain, the Netherlands, Sardinia, Naples, and Tuscany against French Republic.

- 1792: Austria and Prussia invade France. The French defeat the invaders and then go on the offensive by invading the Austria Netherlands (modern Belgium) in late 1792. This causes grave tension with Britain as it was British policy to ensure that France could not control the "narrow seas" by keeping the French out of the Low Countries.

- 1792: In India, victory over Tipu Sultan in Third Anglo-Mysore War; cession of one half of Mysore to the British and their allies.

- 1793: France declares war on Britain.

- 1794: Jay Treaty with the United States and normalizes trade; British withdraws from forts in Northwest Territory; decade of peace with U.S. France is angered seeing a violation of its 1777 treaty with the U.S.[66]

- 1802–03: Peace of Amiens allows 13 months of peace with France.[67]

- 1803: Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815) against France[68]

- 1803–06: War of the Third Coalition: Napoleon closes out the Holy Roman Empire.

- 1803: By the Anglo-Russian agreement, Britain pays a subsidy of £1.5 million for every 100,000 Russian soldiers in the field. Subsidies also went to Austria and other allies.[69][70]

- 1804: Pitt organized the Third Coalition against Napoleon; it last until 1806 and was marked by mostly French victories

- 1805: Decisive defeat of the French navy at the Battle of Trafalgar by Nelson; end of invasion threats

- 1806–07: Britain leads the Fourth Coalition in alliance with Prussia, Russia, Saxony, and Sweden. Napoleon leads France to victory at numerous major battles, notably Battle of Jena–Auerstedt)

- 1807: Britain makes the international slave trade criminal; Slave Trade Act 1807; US criminalizes the international slave trade at the same time.[71]

- 1808–14: Peninsular War against Napoleonic forces in Spain; result is victory under the Duke of Wellington[72]

- 1809-1815. Royal Navy defeats French and seizes Ionian Islands. British gain them in 1815 and designate a new colony, United States of the Ionian Islands. It was ceded to Greece in 1864.[73]

- 1812–15: US declares War of 1812 over national honour, neutral rights at sea, British support for western Indians.[74]

- 1813: Napoleon defeated at Battle of the Nations; British gains and threatens France

- 1814: France invaded; Napoleon abdicates and Congress of Vienna convenes

- 1814: Anglo-Nepalese War (1814–1816)

- 1815: With the War of 1812 against the U.S. a military draw, the British abandon their First Nation allies and agree at the Treaty of Ghent to restore the prewar status quo; thus begins a permanent peace along the US-Canada border, marred only by occasional small, unauthorised raids[75]

- 1815: Napoleon returns and for 100 days is again a threat; he is defeated at the Battle of Waterloo and exiled to a distant island; the Napoleonic Wars end, marking the start of the Britain's Imperial Century, 1815–1914.

- 1815: Second Kandyan War (1815) – in Ceylon (now Sri Lanka)

1815–1860

- 1814–22: Castlereagh as Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs (foreign minister) works with the Congress of Vienna to provide a peace in Europe consistent with the conservative mood of the day. His Congress system sees the main powers meeting every two years or so to collectively manage European affairs. It resolves the Polish-Saxon crisis at Vienna and the question of Greek independence at Laibach. The following ten years saw five European Congresses where disputes were resolved with a diminishing degree of effectiveness. Finally, by 1822, the whole system had collapsed.[76] During this period, Russia emerges as Britain's main enemy, mostly because of tensions associated with the Eastern Question. Anglo-Russian rivalry only ends in the early 20th century.

- 1817: Third Anglo-Maratha War (1817–1818) – India

- 1818: Rush–Bagot Treaty with the United States ends incipient naval race on the Great Lakes. Both powers impose limitations on how many warships they will maintain on the Great Lakes.

- 1822–27: George Canning in charge of foreign policy, avoids co-operation with European powers; supports the United States (Monroe Doctrine) to preserve newly independent Latin American states; goal is to prevent French influence and allow British merchants access to the opening markets. Temperley summarizes Canning's policies, which formed the basis of British foreign policy for decades:

- non-intervention; no European police system; every nation for itself, and God for us all; balance of power; respect for facts, not for abstract theories; respect for treaty rights, but caution in extending them … a republic is as good a member of the comity of nations as a monarch. 'England not Europe.' 'Our foreign policy cannot be conducted against the will of the nation.' 'Europe's domain extends to the shores of the Atlantic, England's begins there.'[77]

- 1821–32: Britain supports Greece in the Greek War of Independence from the Ottoman Empire; the 1832 Treaty of Constantinople is ratified at the London Conference of 1832.

- 1824: Anglo-Dutch Treaty of 1824 is signed.

- 1824: First Anglo-Burmese War (1824–1826) in Burma

- 1830–65: Lord Palmerston dominates British foreign policy; his goal was to keep Britain dominant by maintaining the balance of power in Europe; he tried to keep autocratic nations like Russia in check; he supported liberal regimes because they led to greater stability in the international system.[78]

- 1833: Slavery Abolition Act 1833 frees slaves in Empire; the owners (who mostly reside in Britain) are paid £20 million.

- 1839: Treaty of London. Britain, Germany and other powers guarantee the neutrality of Belgium; Germany violated it in 1914, so Britain declared war.[79]

- 1839: Syrian War (1839–40)

- 1839–1842: First Anglo-Afghan War

- 1840: Oriental Crisis. The ambitions of Muhammad Ali, the more or less independent Ottoman governor of Egypt supported by France to take over the Ottoman Empire nearly causes an Anglo-French war.[80]

- 1842: Treaty of Nanking follows military victory in First Opium War with China (1839 to 1842). It opens trade, cedes territory (especially Hong Kong), fixes Chinese tariffs at a low rate, grants extraterritorial rights to foreigners, and provides both a most favoured nation clause, as well as diplomatic representation.[81]

- 1845: Blockade of the Río de la Plata. To block the ambitions of the Argentine dictator Juan Manuel de Rosas to take over Uruguay, Britain and France impose a five-year blockade on the Río de la Plata.

- 1845: Oregon boundary dispute threatens war with the United States.[82]

- 1846: Oregon Treaty ends dispute with the United States. Border between British North American and the United States settled on the 49th parallel.[83][84]

- 1846: The Corn Laws are repealed; free trade in grain[85]

- 1848–49. Second Sikh war; the British East India Company subjugates the Sikh Empire, and annexes Punjab

- 1852: Second Burmese war; British Burma annexed; the remainder of Burma is annexed after the Third Anglo-Burmese War in 1885.[86]

- 1853–56: Crimean War with Russia. British policy, in league with France, is to protect the decaying Ottoman Empire from Russian advances. The war itself is largely fought on the Crimean peninsula in southern Russia, and is mishandled by both sides. British naval success in the Baltic forces Russia to sue for peace; it demilitarises the Black Sea, ensuring British dominance of the eastern Mediterranean.[87]

- 1856: Second Opium War with China.[88]

- 1857: Indian Mutiny suppressed[89]

- 1858: The government of India transferred to the crown; the government appoints a viceroy.

- 1858: The Anglo-Japanese Treaty of Amity and Commerce is signed.

- 1860: Treaty of Tientsin and Convention of Peking. End of war with China. Deeper British commercial involvement in China.[90]

1860–1896

- 1860–1870: The British government gives moral and diplomatic support to the "Risorgimento" (Unification of Italy creation of the modern Italian state against considerable international opposition.[91] The famed hero of unification, Giuseppe Garibaldi was widely celebrated in Britain.

- 1861: Britain, Spain and France land forces in Mexico to demand repayment. Britain and Spain withdraw but France escalates and takes control of Mexico.

- 1861–65: Neutrality in American Civil War, although Prime Minister Palmerston favours the Confederacy and is tempted to recognise the Confederacy, which would lead to war with US.[92]

- 1861: War scare over Trent Affair resolved when US releases Confederate diplomats seized from a British ship.[93]

- 1864: Britain avoids involvement in the War between Denmark on the one side and Prussia and Austria regarding the Schleswig-Holstein question.[94]

- 1865: Anglo-Moroccan Accords signed by John Drummond-Hay helps preserve Moroccan independence during the Scramble for Africa but reduces the sultanate's customs and royal trade monopolies.

- 1867: British North America Act, 1867, creates Canada, a federation with internal self-government; foreign and defence matters handled by London. The long-term goal is for Canada to pay for its own defence.

- 1868 to 1881: Gladstone formulates a moralistic policy regarding Afghanistan.[95]

- 1871: Taking advantage of France's distress, Russia abrogates the 1856 Treaty of Paris and remilitarises the Black Sea. The action is approved at the London Convention of 1871. Revival of rivalry with Russia in the Near East.[96]

- 1871: Treaty of Washington with the United States, sets up arbitration that settles the Alabama Claims in 1872 in US favour.

- 1871: The unification of Germany following its defeat of France leads the government to expand the Army, and put Edward Cardwell in charge of modernizing the forces.[97][98]

- 1873: The Imperial College of Engineering opens in Tokyo with Henry Dyer as principal; Japan studies and copies British technology and business methods

- 1874–1880. The Conservative government of Benjamin Disraeli scored a number of achievements. In 1875 came the purchase of the controlling shares in the Suez Canal company. By negotiations, Russia gave up substantial gains in the Balkans and a foothold in the Mediterranean. Britain gains control of Cyprus from the Ottomans as a naval base covering the Eastern Mediterranean. In exchange, Britain guaranteed the Asiatic territories of the Ottoman Empire. Britain did not do well in conflicts in Afghanistan and South Africa.[99]

- 1875–1900: Britain joins in the Scramble for Africa with major gains in East Africa, South Africa, and West Africa, and keeps "temporary" control of Egypt. [100]

- 1875–1898: Tensions with France were high over African colonies. At the Fashoda Incident in 1898 fighting was possible, but France retreated and tensions ended.[101]

- 1875: The British government purchases the Suez Canal shares from the almost bankrupt khedive of Egypt, Isma'il Pasha. French investors own the majority of shares.[102]

- 1875–78: Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli works during the Near East crisis to diminish rival Russian interests in the Ottoman Empire. He gained what he wanted at the Congress of Berlin (1878), but did not find a solution to the Eastern Question in the Balkans.[103]

- 1876: Bulgarian Horrors causes outrage in Britain. Gladstone stages nationwide speaking tour attacking Disraeli government for its support of the Turks.[104]

- 1877–78: Russian-Turkish War ends in a Russian victory. The Treaty of San Stefano is widely seen as an unacceptable increase in Russian power in the Balkans.

- 1878: Widespread "jingoism" celebrates sending a British fleet into Turkish waters to counter the advance of Russia.

- 1878: Treaty of Berlin gives Britain possession of Cyprus. Britain leases Cyprus from Turkey in order to block possible Russian expansion. In 1914 Britain annexed Cyprus and made it a crown colony in 1927. Disraeli boasts that he secured "Peace with honour" as well as Cyprus.[105]

- 1879: Egypt goes bankrupt. Loss of Egyptian financial independence to a consortium of European bankers. Evelyn Baring sent to reorganise the Egyptian government in order that Egypt could pay off its debts.[106]

- 1879: Anglo-Zulu War. British forward policy in South Africa aiming at complete control of the country as Britain wishes to maintain control over the alternative Cape route in case the Suez Canal should not be available.

- 1880: Foreign policy is a major issue in the British general election, helping Liberals under Gladstone to defeat Disraeli's Conservative Party by a landslide.[107]

- 1880–81: First Boer War; Britain defeated by the South African Republic of the Afrikaners

- 1880s: Gladstone calls for a "Concert of Europe" – a peaceful European order that overcomes traditional rivalries by emphasising co-operation over conflict, mutual trust over suspicion. He proposes that the rule of law should supplant the reign of force and begger-thy-neighbor policies. However, he was outmaneuvered by Bismarck's system of "realpolitik" using manipulated alliances and antagonisms.[108]

- 1881: Pretoria Convention ends war with the Transvaal and Orange Free State. Henceforward, the Boer republics are independent with a vague British claim of suzerainty. Source of much future tension as the Boer republics see themselves as completely independent states while Britain does not.

- 1882: Uprising in Egypt led by Ahmed Orabi against the foreign control of the government. British take control of Egypt after a war (although it remains nominally part of Ottoman Empire).

- 1883: United Kingdom–Korea Treaty of 1883 is signed.

- 1883–1907: Lord Cromer rules Egypt as consul general[109]

- 1885: The Panjdeh incident causes a war scare with Russia.

- 1885–1902: Historians agree that Lord Salisbury as foreign minister and prime minister was a strong and effective leader in foreign affairs. He had a superb grasp of the issues, and proved:

- a patient, pragmatic practitioner, with a keen understanding of Britain's historic interests....He oversaw the partition of Africa, the emergence of Germany and the United States as imperial powers, and the transfer of British attention from the Dardanelles to Suez without provoking a serious confrontation of the great powers.[110]

- 1886: Witwatersrand Gold Rush. Gold is discovered in the Transvaal. The new wealth of the South African Republic threatens to undermine the assumptions behind the Pretoria convention as it was felt that the two Boer republics were too small and weak to threaten British rule over the Cape Colony and Natal, and thus British control over the Cape route to India. Now with gold being mined in the Witwatersrand, the South African Republic uses its new wealth to go on an arms-buying spree in Europe, which potentially could threaten the British position in South Africa. Renewed British push to bring all of southern Africa under its control.

- 1887: To protect the Suez Canal and the sea lanes to India and Asia, Prime Minister Salisbury signs the Mediterranean Agreements (March and December 1887) with Italy and Austria. This aligns Britain indirectly with Germany and the Triple Alliance.[111]

- 1889: Salisbury increases he dominance of the Royal navy through the Naval Defence Act 1889, with an extra £20 million for ten new battleships, thirty-eight new cruisers, eighteen new torpedo boats and four new fast gunboats.

- 1890–1896: Britain suffers a series of diplomatic reverses, including the abandonment of the Congo treaty with Belgium; the French conquest of Madagascar; the collaboration of France, Russia and Germany in the Far East; the Venezuela crisis with United States; the Armenian massacres in the Ottoman Empire; the emerging alliance between France and Russia; and the debacle of the Jameson Raid; debates focus on Britain's lack of allies.[112]

- 1890–1902: Salisbury promotes a policy of Splendid isolation with no formal allies.[113]

- 1890: The South African Republic passes a law that disenfranchised most of the uitlanders as foreign, mostly British workers in the Transvaal's gold fields are known. The uitlander issue becomes a major source of strain and tension in the following decade.

- 1890: Heligoland–Zanzibar Treaty with Germany. Britain gains the German colony of Zanzibar while giving up a small strategic island off the German coast, and agrees on boundaries in Africa.[114]

President Cleveland twists the tail of the British Lion regarding Venezuela—a policy hailed by Irish Catholics in the United States; cartoon in Puck by J.S. Pughe, 1895

- 1895: Venezuela Crisis. Border dispute with Venezuela causes major Anglo-American crisis when the United States intervenes to take Venezuela's side. It was resolved through arbitration and was last crisis that threatened war with the United States.[115]

- 1894–96: Britain puts pressure on Turkey to stop its mistreatment of Christians. A series of escalating atrocities against the Armenians living in Turkey causes public outrage in Britain. All efforts to coordinate sanctions or punishments with the other Powers fail, and the Armenians get no help.[116][117]

- 1895–96: Jameson Raid. Botched attempt at a coup to overthrow President Paul Kruger of the South African Republic, instigated by Cecil Rhodes. The result was to strengthen Afrikaner nationalism and embarrass Britain.[118]

- 1896: January – Germany's Kaiser Wilhelm escalated tensions with his Kruger telegram of January 1896 congratulating President Kruger of the Transvaal for beating off the Jameson raid. German officials in Berlin had managed to stop the Kaiser from proposing a German protectorate over the Transvaal. The telegram backfired, as the British began to see Germany as a major threat and moved to friendlier relationships with France.[119]

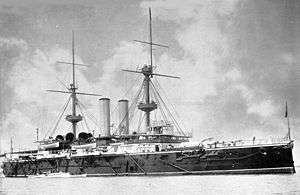

The battleship HMS Royal Sovereign, 1896

1897–1919

- 1897: Admiral Alfred von Tirpitz appointed German Naval Secretary of State; beginning of the transformation of German Navy from small, coastal defence force to a fleet meant to challenge British naval power. Tirpitz calls for Riskflotte (Risk Fleet) that would make it too risky for Britain to take on Germany as part of wider bid to alter the international balance of power decisively in the Reich"s favour.[120]

- 1897: German Foreign Secretary Bernhard von Bülow calls for Weltpolitik (World politics). New policy of Germany to assert its claim to be a global as opposed to a European power. Germany abandons Bismarck-era policy of being a conservative power committed to upholding the status quo, and instead becomes a revisionist power intent on challenging and upsetting international order. It was now the policy of Germany to assert its claim to be a global power. The long-run result was the inability of Britain and Germany to be friends or to form an alliance.[121]

- 1898: First Navy Law passed in Germany that commits the Reich to building up its fleet to achieve Tirpitz's vision.[122]

- 1898: Convention for the Extension of Hong Kong Territory with China.[123]

- 1898: Anglo-Egyptian control over Sudan established.[124]

- 1898: Fashoda Incident threatens war with France over control of upper Nile River (in present-day eastern South Sudan); the French back down. The long-term British goal is to link South Africa to Egypt with the Cape to Cairo Railway. It would facilitate governance, give rapid mobility to the military, promote settlement and foster trade. Most of the railway is eventually built, but there were gaps.[125]

- 1898: Spanish–American War. Britain maintains pro-American neutrality. Anglo-American relations began to improve markedly at the end of the 19th century.[126]

- 1899: Britain endorses the "Open Door Policy" allowing the world access to Chinese markets.[127]

- 1899: Bloemfontein Conference between Alfred Milner, the British High Commissioner for South Africa and President Paul Kruger of the Transvaal. Principal issue the status of the uitlanders and the English language together with Milner's demand that the Transvaal's sovereignty be sharply reduced. Conference ends in failure.[128]

- 1899: Colonial Secretary Joseph Chamberlain's offer of an alliance with Germany is refused by Berlin.[129]

- 1899: Beginning of the Second Boer War when the Transvaal (South African Republic) declares war on Britain.[130][131]

- 1899: The first Hague Conference was a major effort to codify the rules for international peace. It set up machinery to help resolve international disputes. Britain and Russia used its procedures in resolving the Dogger Bank incident of 1904. It established a Permanent Court of Arbitration. It did little to slow the arms race in Europe. Its declaration banning the use of poison gas was simply ignored.[132]

- 1900: British forces join in international rescue in Peking, China, & suppress the anti-Western Boxer Rebellion.[133]

- 1900: Second Navy Law passed in Germany calling for huge increase in the size of the German Navy.

- 1901: Hay–Pauncefote Treaty with US nullifies Clayton–Bulwer Treaty of 1850; allows U.S. to build the Panama Canal & guarantees open passage for any nation. Panama Canal opens in 1914.[134]

- 1902: Lenient Treaty of Vereeniging. Boer War ends in a British victory; Transvaal and Orange Free State are annexed and in 1910 become part of Union of South Africa. Boer leaders especially Jan Smuts accepted as British leaders.[135]

- 1902: Reports from Captain Watson, naval attaché to Germany indicate that the German build-up that had begun in 1898 is intended to build a fleet meant to challenge British sea power. Beginning of the Anglo-German naval race.[136]

- 1902: The Anglo-Japanese Alliance is signed; in 1905 it is renewed and expanded; it is not renewed in 1923.[137]

- 1903: King Edward VII, new to the throne but long familiar with France, makes a highly successful visit to Paris, turning hostility into friendship.[138]

- 1903: Younghusband expedition to Tibet. Britain invades Tibet to counter supposed Russian influence at the court of the Dali Lama that seems to be threatening India.[139]

- 1904: Beginning of the Russo-Japanese War. Britain supports Japan while France and Germany support Russia. Britain shares signet (signals intelligence) with Japan against Russia.[140] Due to shared intelligence with Japan, British decision-makers increasingly come to the conclusion that Germany is supporting Russia as part of a bid to disturb the balance of power in Europe.[141]

- 1904: 8 April. Three agreements with France ("Entente cordiale") end many points of friction. France recognises British control over Egypt, while Britain reciprocates regarding France in Morocco. France drops exclusive fishery rights on the shores of Newfoundland and in return receives an indemnity and territory in Gambia (Senegal) and Nigeria. Britain drops complaints regarding the French customs régime in Madagascar. Spheres of influence are defines in Siam (Thailand). Issues regarding New Hebrides are settled in 1906. Which means doing we see its rights in Egypt, it became possible for the British to significantly extend their control. The Entente was negotiated between the French foreign minister, Théophile Delcassé, and the British foreign secretary, Lord Lansdowne.[142]

- 1904: Convention with Tibet allowing a British trade mission to be established and is intended to pull Tibet within the British sphere of influence.[143]

- 1904: Dogger Bank incident. Russian Baltic fleet en route to Korea to fight Japan accidentally fires on British fishing trawlers. Britain and Russia almost go to war. Crisis ends when Russia apologises and pays compensation.[144]

- 1905: First Moroccan Crisis. Germany threatens war with France in an attempt to break entente cordiale. Britain makes it clear that in the event of a German attack on France, Britain will intervene on France's side.[145]

- 1905: Persian Constitutional Revolution causes tension with Russia. Britain supports Persian liberals while Russia supports the Shah.[146]

- 1906: Algeciras Conference ends the Moroccan Crisis in a diplomatic defeat for Germany as France took the dominant role in North Africa. The Crisis brought London and Paris much closer and set up the presumption they would be allies if Germany attacked either one.[147]

- 1906: Britain reacted to Germany's accelerated naval arms race by major innovations, especially those developed by Lord Fisher. The launch of HMS Dreadnought rendered all other battleships technically obsolete and marked British success in maintaining both qualitative and quantitative lead in the naval race with Germany.[148]

- 1906: Third Navy Law passed in Germany. Germany plans to build "all big gun" ships of its own to keep up with Britain in the naval race.

The Triple Entente formed 1907 (in grey) versus the Triple Alliance of 1882–1914, shown in red.

- 1907: Anglo-Russian Entente was achieved and outstanding disputes between Britain and Russia settled. It ended The Great Game regarding control of Tibet, Persia, and Afghanistan.[149]

- 1907: Triple Entente with France and Russia, stands opposed to the Triple Alliance of Germany, Austria and Italy.[150]

- 1908: Fourth Navy Law passed in Germany; British popular response was a clamour for more warship construction under the slogan "We want eight and won't wait" when it appears that Germany is winning the naval race.

- 1911: Reports from Captain Watson, naval attaché to Germany indicate growing power and efficiency of German warships, heavy guns and sailors.[151]

- 1911: Agadir Crisis France strong-armed itself into seizing more control over Morocco. The German Foreign Minister Alfred von Kiderlen-Waechter was not opposed to these moves, but he felt Germany was entitled to some compensation elsewhere in Africa. He sent a small warship, made saber-rattling threats, and whipped up anger among German nationalists. France and Germany soon agreed on a compromise. However, the British cabinet was alarmed at Germany's aggressiveness toward France. David Lloyd George made a dramatic "Mansion House" speech that denounced the German move an intolerable humiliation. There was talk of war, and Germany backed down. Relations with Berlin remained sour.[152]

- 1911: Reciprocity treaty lowering tariffs between Canada and US fails on surge of pro-British, anti-American sentiments led by Conservative Party.[153]

- 1912: Fifth Navy Law passed in Germany Expanding the German fleet as a threat to the Royal Navy's control of the seas.

- 1912: Haldane Mission to Germany. Richard Haldane visits Berlin to meet with high officials in an attempt to end the naval race with Germany. Haldane's offer of a "naval holiday" in building warships ends in failure when the Germans attempt to link a "naval holiday" with a British promise to remain neutral if Germany should attack France; Admiral Tirpitz orders further naval construction.[154][155]

- 1914: July Crisis triggered when Austria-Hungary submits ultimatum to Serbia containing terms meant to inspire rejection. Foreign Secretary Edward Grey tries hard to maintain peace and mediate a compromise, but falls short.

- 1914: 4 August- The king, in the name of Britain and his Empire declares war on Germany and Austria following German violation of the neurality of Belgium.

- 1914: Stalemate on Western Front, but Britain & dominions seize the overseas German colonies

- 1915: British passenger liner RMS Lusitania torpedoed without warning by German submarine and sinks in 18 minutes; 1,200 dead. Germany violated international law by not allowing passengers to escape.

- 1915: Treaty of London brings Italy into the war on the Allied state. Italy is secretly promised major gains at the expense of Austria-Hungary.

- 1916: Sykes–Picot Agreement is signed. Britain and France decide on spheres of influence if the Ottoman Empire should come to an end.

- 1917: 7 April. US declares war on Germany and Austria; does not actually join Allies and remains independent force; sends token army in 1917. A major factor in bringing the United States into war is the Zimmermann Telegram, a German proposal for anti-American alliances with Mexico and Japan that was intercepted, decoded and leaked by the British.

- 1917: Balfour Declaration is issued giving British support for a Jewish "national home" in Palestine.

- 1918: Britain accepts the Fourteen Points, the American statement of war aims.

- 1918: Beginning of British intervention in the Russian Civil War. After the end of World War I, Britain will be the biggest supporter of the Russian White forces.

- 1918: November. Britain and Allies defeat Germany, Austria-Hungary and Turkey; their empires dissolved (along with Russian Empire)

- 1919: Treaty of Versailles Prime Minister David Lloyd George was a key negotiator. In the Khaki Election of 1918, coming days after the Allied victory over Germany, Lloyd George promised to impose a harsh treaty on Germany. At the Versailles Conference, however, he took a much more moderate approach. France and Italy however demanded and achieved harsh terms, including German admission of guilt for starting the war (which humiliated Germany), and a demand that Germany pay the entire Allied cost of the war, including veterans' benefits and interest.[156]

- 1919: League of Nations formed, with Britain an active member, along with the Dominions and India

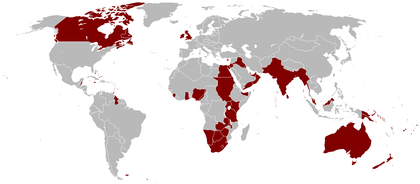

British Empire in 1921

1920–1934

- 1919: Greco-Turkish War begins. Britain was chief supporter of Greece, but it did poorly.[157]

- 1919: War Secretary Winston Churchill introduces the Ten Year Rule that military spending is to be based on the assumption that there will be no major war for the next ten years. The Ten Year Rule leads to a huge decline in military spending.[158]

- 1920: Leonid Krasin visits London to meet Lloyd George. First official contact between Soviet Russia and Britain.[159]

- 1921: Anglo-Soviet Trade Agreement is signed. First treaty between Britain and Soviet Russia.[160]

- 1921: Franklin-Bouillon Agreement is signed. France supports Turkey in the Greco-Turkish War while Britain continues to support Greece.[161]

- 1922: Washington Naval Conference concluding in the Four-Power Treaty, Five-Power Treaty, and Nine-Power Treaty; major naval disarmament for 10 years with sharp reduction of all major navies. Britain abandons claim to have navy "second to none", and recognises United States Navy as equal. The costs of naval races with the U.S. and Japan are prohibitively expensive for a British economy weakened by World War I. The relative naval strengths of the major powers are fixed at GB = 5, US = 5, Japan = 3, France = 1.75, Italy = 1.75. Britain does not build up to its allowed maximum. The powers will abide by the treaty for ten years, then begin a naval arms race.[162][163]

- 1922: League of Nation awards Britain a mandate to control Palestine, which it had conquered from the Ottoman Empire in 1917. The mandate lasts until 1948.[164]

- 1922: Genoa conference. Britain clashes openly with France over the amount of reparations to be collected from Germany.[165]

- 1922: Alliance with Japan ends; Canada and Australia disliked the treaty, as did the U.S.[166]

- 1922: Chanak Crisis. Britain almost goes to war with Turkey. Some of the Dominions refuse to promise to war if Britain does, which comes as a major shock in Whitehall. The intention of Lloyd George to go to war with Turkey causes the downfall of his government.[167]

- 1923: The British government renegotiated its £978 million war debt to the US Treasury by promising regular payments of £34 million for ten years then £40 million for 52 years. The idea was for the US to loan money to Germany, which in turn paid reparations to Britain, which in turn paid off its loans from the US government. In 1931 all German payments ended, and in 1932 Britain suspended its payments to the US. All the First World War debts were finally repaid after 1945.[168]

- 1923: France occupies the Ruhr following German default in reparations. Britain wanted Germany's economy to revive, so could make reparation payments and increased trade. France rejected Britain's argument, and along with Belgium occupied the Ruhr 1922–25. British policy was then uncertain, until it hit on the idea of inviting the Americans to resolve the problem, which was done with the Dawes Plan.[169][170][171]

- 1923: Treaty of Lausanne with Turkey. Britain was forced to make major concessions to the Turks as compared to the previous Treaty of Sèvres of 1920.[172]

- 1924: London conference between Labour Prime Minister Ramsay MacDonald and French Premier Édouard Herriot. Britain forced France to reduce the amount of reparations to be collected from Germany. The British diplomat Sir Eric Phipps commented that "The London Conference was for the French 'man in the street' one long Calvary as he saw M. Herriot abandoning one by one the cherished possessions of French preponderance on the Reparations Commission, the right of sanctions in the event of German default, the economic occupation of the Ruhr, the French-Belgian railroad Régie, and finally, the military occupation of the Ruhr within a year".[173]

- 1924: The Geneva Protocol, (Protocol for the pacific settlement of international disputes) was a proposal to the League of Nations presented by Prime Minister Ramsay MacDonald, and his French counterpart Édouard Herriot. It set up compulsory arbitration of disputes, and a created a method to determine who was the aggressor in international conflicts. All legal disputes between nations would be submitted to the World Court. It called for a disarmament conference in 1925. Any government which refused to comply in a dispute would be named an aggressor. Any victim of aggression was to receive immediate assistance from the League members. McDonald lost power and the new Conservatives government condemned the proposal, fearing it would lead to conflict with the United States. Washington also opposed it, and so did all the British dominions. The proposal was tabled in 1925 and never went into effect.[174][175]

- 1924: Labour government establishes diplomatic relations with Soviet Russia.[176]

- 1925: Locarno Treaties normalise the status of Germany, although the provisions of the Versailles Treaty still apply; begins a decade of British efforts to stabilise a new European status quo, hoping that stability, plus trade, would prevent another war.[177][178]

- 1926: Dispute with Turkey over Mosul ends. Turkey ends claim to Mosul region of Iraq.[179]

- 1927: British police raid ARCOS office in London. Relations with the Soviet Union are broken off following discovery of the Soviet spy ring operating out of the ARCOS building.[180]

- 1929: MacDonald's Labour government restores relations with the Soviet Union.[181]

- 1929: MacDonald visits the United States; first visit to the US by a sitting British Prime Minister.[182]

- 1929–31: Labour Foreign Minister Arthur Henderson gives strong support to League of Nations.[183]

- 1931: Statute of Westminster recognises the full independence to the Dominions.[184]

- 1932: British policy in the Far East faces a crisis in 1932, when the Japanese attacked Shanghai. Of all British foreign investment, 6% is in China and two-thirds of that is in Shanghai. As a result, the Ten Year Rule is dropped. (It said the military planning should assume that no war would take place in the next ten years.) The Cabinet authorises a modest increase in the Royal Navy budget based on the assumption that there might a war with Japan sometime within the next decade, through constraints imposed by the Great Depression limit how much money will be spent. Beginning of British rearmament.[185]

- 1932: Britain suspends its World War I debt payments to the United States.

- 1934: A secret report by the Defence Requirements Committee identifies Germany as the "ultimate potential enemy"; calls for Continental expeditionary force of five mechanised divisions and fourteen infantry divisions. Budget restraints prevent formation of this large force.[186]

- 1934: Beginning of the "air panic" of 1934–35, where exaggerated claims of German air strength are made in the British press. Royal Air Force becomes the main beneficiary of rearmament.[187]

1935–1945

- 1935: The Peace Ballot is held with 11.5 million votes cast. The strong affirmative vote was ambiguous and the campaign was distorted by bias. Political leaders ignored it as an expression of wishful thinking rather than a serious statement of foreign policy.[188][189]

- 1935: Stresa Front formed following summit between Prime Minister Ramsay MacDonald, French Premier Pierre Laval and Italian Prime Minister Benito Mussolini vaguely sought to oppose any challenge to the Treaty of Versailles via force. Mussolini mistakenly feels that Britain has no interest in Ethiopia.[190]

- 1935: Anglo-German Naval Agreement signed in London. It is meant to avoid a repeat of the pre-1914 Anglo-German naval race.[191]

- 1935: Italy invades Ethiopia. Beginning of a crisis in Anglo-Italian relations as Britain makes half-hearted attempts to uphold collective security. Mussolini threatens of war against Britain.[192]

- 1935: Election of 1935 takes place. Government of Stanley Baldwin is returned to power with a promise to uphold collective security.

- 1935: Hoare–Laval Pact with France proposes to appease Italy and evades League sanctions against Italy for invading Ethiopia. The proposal was approved by the cabinet but public reaction is highly negative and Foreign Minister Samuel Hoare is forced to resign, replaced by Anthony Eden.[193][194][195]

- 1936: Remilitarization of the Rhineland. Germany remilitarises the German Rhineland in explicit violation of the Versailles and Locarno treaties which said the area had to remain without soldiers. The Baldwin government protested, but valued peace highly and did not take action. France had sufficient military superiority to expel Germany from the Rhineland but instead chose to follow Britain and do nothing. It lacked confidence in its military and feared another costly war.[196][197]

- 1936–39: British opinion is deeply split on the Spanish Civil War with the government tending to favour the right-wing Nationalists while intellectuals and unions favoured the Republic because it was anti-Fascist. Communists were leaders in protest efforts, and enlisted 2500 British and Irish volunteers go to Spain to fight for the Republic; 500 were killed.[198] The government joins major powers in proclaiming neutrality and opposes arms shipments to either side, fearing the war might spread. Nevertheless, Germany and Italy supply the Nationalists and the USSR supplies the Republicans. The Nationalists under Francisco Franco are completely victorious in 1939.[199]

- 1937: Japanese planes attack British gunboats in the Yangtze River and machine-gun the car of the British Ambassador to China, Sir Hughe Knatchbull-Hugessen, who is badly injured. As these attacks occurred at the same time as the sinking of USS Panay, Britain suggests that an Anglo-American blockade of Japan as a response. The American President Franklin Roosevelt refuses the British offer and instead accepts Japanese apology, through he does allow the secret Anglo-American naval talks to be begin in early 1938.

- 1938: Mexican oil expropriation. The government of Lázaro Cárdenas nationalises land owned by British oil companies in Mexico.[200]

- 1938: Anglo-Italian Easter Accords are signed. Britain tries to restore relations with Italy.[201]

- 1938: Foreign Secretary Anthony Eden used secret intelligence reports to conclude Italy was an enemy. He resigned in protest over Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain's moving closer to Italy to block Germany.[202]

- 1938 – Hitler threatens war over the alleged mistreatment of ethnic Germans in the Sudetenland, a part of Czechoslovakia. Intense appeasement efforts by Britain and France to avoid war by concessions to Germany. Czechoslovakia is not consulted.[203]

- 1938: Britain and France signed the Munich Agreement with Nazi Germany. Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain promises it means "peace in our time." Historians differ sharply; some argue the appeasement was cowardice; others argue it saved Britain, which was not prepared for war with Germany.[204][205]

- 1939: Jan. – Appeasement policy ends as Germany seizes all of Czechoslovakia

- 1939: 31 March- Prime Minister Chamberlain issues "guarantee" of Polish independence in the House of Commons in co-operation with France; they will go to war should Polish independence be threatened.

- 1939: Tientsin Incident. Britain and Japan almost to war when Japan blockades British concession in Tianjin, China.[206]

- 1939: Britain signs a defence treaty with Poland, guaranteeing its boundaries against German threats.[207]

- 1939: 1 September- Germany invades Poland; Britain and France declare war on 3 September.

- 1939–40: "Phoney war" with little action on the Western Front

- 1940: British army trapped and narrowly escapes at Dunkirk.[208]

- 1940: September. Britain trades bases on its colonies in the Western Hemisphere for destroyers from the United States. The destroyers were used to defend convoys. The colonies were used as bargaining counters to secure American friendship and to minimize creeping American influence.[209]

- 1941: January – Britain informs the United States that unless aid is offered, Britain will be bankrupt later that year.

- 1941: The United States begins Lend-Lease to support Allied war effort; $31.4 billion is given away to Britain and $11.3 billion to the Soviet Union. Canada in a separate programs gives $4.7 billion. Unlike American aid in 1917–18, Lend Lease is not a loan and does not have to be repaid.[210][211]

- 1941, 22 June – Germany launched Operation Barbarossa invading the USSR, which became one of the Allies of World War II fighting against the Axis powers.

- 1941: Prime Minister Churchill agrees on Atlantic Charter with President Roosevelt.[212]

- 1941: The Anglo-Soviet invasion of Iran occupied a neutral country on pretext that Iran didn't let go of German advisors in Iran.

- 1941–45: The Arctic convoys transported supplies Britain gave without charge to the USSR during the war.[213]

- 1941: Japan attacks the United States, Britain and the Netherlands. Japanese seize Hong Kong, Brunei, Malaya, Sabah, Sarawak, Singapore, and Burma; Gross mistreatment of prisoners of war.[214]

- 1942: Britain and USSR agree that after victory Poland's boundaries would be moved westward, so that the USSR took over lands in the east while Poland gained lands in the west that had been under German control. They agreed on the "Curzon Line" as the boundary between Poland and the Soviet Union and the Oder-Neisse line would become the new boundary between Germany and Poland. The proposed changes angered the Polish government in exile in London, which was not consulted.

- 1943: A. J. P. Taylor asserts, "1943 was the year when world leadership moved from Great Britain to the United States."[215]

- 1943: The Casablanca Conference in Morocco, 14–23 January, brought together Churchill, Roosevelt and Charles de Gaulle. The Allies announced a policy of "unconditional surrender" from the Axis powers.[216]

- 1943: Aug. Quebec Conference ("Quadrant"). Combined Chiefs (US and UK) agree on 29 divisions to land in France in Operation Overlord in May 1944. Plans also discussed re landings in southern France, and operations in Burma, China and Pacific, and to share atomic bomb project.[217]

- 1943: An agreement is signed ending all British extraterritorial rights in China.

- 1944: Argentina refused to go along with the American anti-German policies. Washington responded by trying to shut down Argentine exports. In 1944 President Franklin Roosevelt asked Prime Minister Winston Churchill to stop buying Argentine beef and grain. Churchill refused, saying the food was urgently needed.[218]

- 1944 September – Churchill and Roosevelt and Combined Chiefs meet in Second Quebec Conference ("Octagon"). Discussion of Pacific strategy; agreement (later revoked) on Morgenthau Plan to demilitarise Germany.[219]

- 1944 October – Churchill and Foreign Minister Eden meet in Moscow with Stalin and his foreign minister Vyacheslav Molotov. They planned who would control what in postwar Eastern Europe. They agreed to give 90% of the influence in Greece to Britain and 90% in Romania to Russia. Russia gained an 80%/20% division in Bulgaria and Hungary. There was a 50/50 division in Yugoslavia, and no Russian share in Italy.[220][221]

- 1944 December- Battle of Athens. British troops battle the Communist ELAS forces for control of Athens.[222]

1945–1989

- 1944–47: The Jewish insurgency in Palestine as Jews confront Arabs and British in quest for independent Israel in Palestine, for which Britain holds the League of nations mandate.[223][224][225]

- 1945: World War II ends. Victory over Germany and Japan. Britain is financially exhausted as Lend Lease aid from the US suddenly ends in August. An "Age of Austerity" and cutbacks begins.

- 1945–46: Parliament approves a $3.75 billion low-interest loan from the US Treasury in 1946,[226] plus $1.2 billion from Canada.[227]

- 1945–1957: Despite tight budgets Britain uses cultural diplomacy in the Middle East. The British Council, the BBC and the official overseas information services mobilises pro-democracy organisations and educational exchanges, as well as magazines, book distribution, and films industry to bolster British prestige and promote democracy.[228]

- 1946: UKUSA Agreement on continuing war-time signet work between the United States and the United Kingdom.

- 1947: The government decides in secret to build an atomic bomb.[229]

- 1947: Government informs the United States that Britain cannot afford to subsidise the Greek government in its Greek Civil War against Communist guerrillas.[230]

- 1947–48: Britain withdraws from the Palestine Mandate it held since 1920 and turns the issue over to the U.N. Financial exhaustion was a main reason, but also strategic concerns, for its involvement was alienating Arab nations whose good will was desired.[231]

- 1948–49: The Berlin Blockade threatens Britain's status in West Berlin. The RAF plays a major role in the Berlin Airlift and the Soviets finally relent.[232]

- 1948–1960: Malayan Emergency, a civil war against the Communist-led Malayan National Liberation Army (MNLA); Britain is victorious in the end.[233]

- 1949: Britain becomes founding member of NATO.[234]

- 1949: Amethyst incident. Frigate HMS Amethyst is fired upon by Chinese Communists on the Yangtze River.[235]

- 1950: Britain recognises China in January, over American objections.[236]

- 1950–1953: Britain fights under the UN flag in the Korean War against Communist forces from North Korea and China.[237]

- 1951: Britain strenuously opposes use of nuclear weapons in Korea as discussed by the US[238]

- 1951: Egypt renounces the 1936 treaty. Egyptians begin guerrilla attacks against the British Suez Canal base. Low-level warfare between British forces and the Egyptians for next several years.

- 1951: Abadan Crisis. The government of Mohammad Mosaddegh in Iran nationalises the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company.

- 1952: In response to Egyptian attacks, British forces storm and take a police station in Ismaïlia. The Ismaïlia incident ignites anti-British rioting all over Egypt.

- 1953: American and British intelligence agencies support coup in Iran.

- 1954: Prime Minister Churchill refuses a French request to intervene in Vietnam.[239]

- 1954: Treaty signed with Egypt ending the British Suez Canal base.

- 1955: Geneva summit attended by Prime Minister Anthony Eden. Last time that a British Prime Minister attended a summit of the super-powers.

- 1955–63: Yemen emerges as a trouble spot in an old-rich region where the Soviets sponsor a revolt. Civil war erupts in 1962 as Britain tries to protect its colony in Aden.[240]

- 1955: Baghdad Pact signed. Alliance intended to maintain British influence in the Near East.

- 1956: In the Suez Crisis Egypt nationalised the Suez Canal, a vital waterway carrying most of Europe's oil from the Middle East. Britain and France, in league with Israel, invaded to seize the canal and overthrow President Nasser. The United States strenuously objected, using heavy diplomatic and financial pressure to force the invaders to withdraw. British policy had four goals: to control the Suez Canal; ensure the flow of oil; remove Nasser; and keep the Soviets out of the Middle East. It failed on all four.[241]

- 1958–60: As the anti-nuclear movement gains momentum, Britain, the US and the USSR suspend nuclear tests and hold test ban talks in Geneva. However Prime Minister Harold Macmillan decides not to criticise French nuclear tests in 1960. His goals were to gain French support for Britain's joining the European Economic Community, and also French backing for a four-power summit to promote détente.[242]

- 1958: Anglo-American nuclear treaty establishes basis for co-operation on nuclear weapons development.

- 1958: Britain sends troops to Jordan to restore order following riots against pro-British King Hussein.

- 1959–1960: Zürich and London Agreement between Britain, Greece and Turkey grants independence to Cyprus.

- 1960: Prime Minister Harold Macmillan gives "wind of change" speech in South Africa. It signals an intention to soon grant independence to the remaining colonies in Asia, the Caribbean and Africa.[243]

- 1961: Britain sends troops to Kuwait following threats by Iraqi leader Abd al-Karim Qasim that he will invade Kuwait. Iraq is deterred from invading.

- 1962–1966: Indonesian confrontation. Britain fights undeclared war against Indonesia in defence of Malaysia.

- 1968: Britain announces withdrawal of military forces "East of Suez".

- 1971: In a reversal of the withdrawal of military forces "east of Suez", Britain signs the Five Power Defence Arrangements with Australia, New Zealand, Malaysia and Singapore. The alliance is intended to protect Singapore and Malaysia from Indonesia.

- 1972: Ugandan dictator Idi Amin expels the so-called "Asians", Ugandans of South Asian background, most of whom hold British pass-ports and come to Britain.

- 1973: Britain joins European Community after France blocked its first application in 1961.[244]

- 1974: Turkey invades Cyprus. Britain is obliged to defend Cyprus under 1960 treaty, but chooses not to.

- 1976: Britain needs bail-out by the IMF to avoid defaulting on debts.[245]

- 1979: Strongly protests Soviet invasion of Afghanistan[246]

- 1980: Death of a Princess airs in Britain. Saudi Arabia breaks relations with Britain over the airing of the film, which it is claimed was insulting towards the House of Saud. Relations restored later that year.

- 1982: Victory in War with Argentina over Falkland Islands[247]

- 1984: Murder of Yvonne Fletcher. British policewoman killed by Libyan diplomat. Britain breaks relations with Libya.

- 1984: Thatcher wins rebate from European Union.[248]

- 1984: Signs treaty with China to return Hong Kong in 1997.[249]

- 1986: Hindawi affair. Britain breaks diplomatic relations with Syria after it emerges that Syria was involved in an attempt to bomb El Air flight out of London.

- 1989: Ruhollah Khomeini issues a fatwa sentencing British author Salman Rushdie to death. Britain breaks diplomatic relations with Iran.[250]

Since 1990

- 1989: Collapse of Communist control in Eastern Europe

- 1990: Thatcher sends troops to Middle East following Iraqi invasion of Kuwait.

- 1990: Two plus four treaty restores full sovereignty to Germany and ends British occupation rights that had existed since 1945.

- 1991: Britain fights in Gulf War against Iraq.

- 1991: Cold War ends as Communism in USSR ends and the USSR is broken up

- 1992: Black Wednesday. Britain forced out of the European Exchange Rate Mechanism.

- 1994: Relations restored with Iran.

- 1997–2007: Prime Minister Tony Blair built his foreign policy on two traditional principles (close ties with US and EU) and a new activist philosophy of 'interventionism'.[251][nb 1]

- 2001: Britain joins war on terror.[253]

- 2001–2014: British combat forces with NATO in Afghanistan;[254] a few hundred troops remain to provide training until 2016.[255]

- 2016: P5+1 and EU implement a deal with Iran intended to prevent the country gaining access to nuclear weapons.[256]

- 2016: The United Kingdom votes for "Brexit" to leave the European Union

- 2016: David Cameron resigns as Prime Minister following his defeat in the Brexit referendum. He was succeeded by Conservative Theresa May.

Prominent diplomats

See the full list at Secretary of State for Foreign and Commonwealth Affairs

- Earl of Clarendon (1800–70). foreign secretary (1865–66, 1868–1870).

- 1st Earl Granville, (1773–1846) known as Viscount Granville from 1815 to 1833, and as Earl Granville from 1833–36; diplomat

- 2nd Earl Granville, (1815–1891), Liberal statesman and diplomat; known for his pacific stewardship of Britain's external relations, 1870–74 and 1880–85, in co-operation with Prime Minister Gladstone.

- Lord Palmerston, (1784–1865) Whig/Liberal foreign minister or prime minister (1830–1865 with interruptions)

- Lord Salisbury (1830–1903) Conservative foreign minister and/or prime minister (1878–1902 with interruptions)

- Joseph Chamberlain, (1836–1914), Liberal Unionist Secretary of State for the Colonies (1895–1903).

See also

- History of the foreign relations of the United Kingdom

- American Revolution

- Anglophobia

- British Empire

- British military history

- List of wars involving England, before 1707

- List of wars involving Great Britain

- English colonial empire

- History of England

- History of the Royal Navy

- History of the United Kingdom, since 1707

- International relations 1648-1814

- International relations of the Great Powers (1814–1919)

- Diplomatic history of World War I

- International relations (1919–1939)

- Diplomatic history of World War II

- Cold War

- Foreign relations of the United Kingdom

- Belgium–United Kingdom relations

- Canada–United Kingdom relations

- China–United Kingdom relations

- Denmark–United Kingdom relations

- Egypt–United Kingdom relations

- France–United Kingdom relations

- Germany–United Kingdom relations

- Greece–United Kingdom relations

- Indonesia–United Kingdom relations

- Iran–United Kingdom relations

- Israel–United Kingdom relations

- Italy–United Kingdom relations

- Japan–United Kingdom relations

- Latin America–United Kingdom relations

- Netherlands–United Kingdom relations

- Poland–United Kingdom relations

- Portugal–United Kingdom relations

- Serbia–United Kingdom relations

- Turkey–United Kingdom relations

- United Kingdom–United States relations

- United Kingdom and the United Nations

Notes

- Military interventions include the 1999 Kosovo peacekeeping force, 2000 intervention in the Sierra Leone Civil War,[252] and the 2003 Iraq War.

References

- John M. Currin, "Henry VII and the treaty of Redon (1489): Plantagenet ambitions and early Tudor foreign policy", History (1996) 81# 263, pp 343–58

- Joycelyne Gledhill Russell, The Field of the Cloth of Gold: Men and Manners in 1320 (1969).

- David M. Loades, The Reign of Mary Tudor: Politics, Government and Religion in England, 1553–58 (1991)

- Charles Beem, The Foreign Relations of Elizabeth I (2011) excerpt and text search

- Benton Rain Patterson, With the Heart of a King: Elizabeth I of England, Philip II of Spain & the Fight for a Nation's Soul & Crown (2007)

- Jane E.A. Dawson, "William Cecil and the British Dimension of Early Elizabethan Foreign Policy", History, June 1989, Vol. 74 Issue 241, pp 196–216

- R.B. Mowat, History of European Diplomacy, 1451–1789 (1928) pp 133–40.

- Maria Blackwood, "Politics, Trade, and Diplomacy: The Anglo-Ottoman Relationship, 1575–1699", History Matters (May 2010), pp 1–34

- R. B. Wernham, Before the Armada: The growth of English foreign policy 1485–1588 (1966)

- Angus Konstam and Angus McBride, Elizabethan Sea Dogs 1560–1605 (2000) p. 4

- Geoffrey Parker, "Why the Armada Failed", History Today (May 1988) pp 26–33.

- G.M.D. Howat, Stuart and Cromwellian Foreign Policy (1974)

- W. B. Patterson (2000). King James VI and I and the Reunion of Christendom. Cambridge U.P. p. 70. ISBN 9780521793858.

- W. B. Patterson, "King James I and the Protestant cause in the crisis of 1618–22." Studies in Church History 18 (1982): 319–334.

- Maija Jansson, Nikolai Rogozhin, and Paul Bushkovitch, eds. England and the North: The Russian Embassy of 1613–1614 (1994).

- Adam Clulow, "Commemorating Failure: The Four Hundredth Anniversary of England's Trading Outpost in Japan." Monumenta Nipponica 68.2 (2013): 207-231. online

- Karen Chancey, "The Amboyna massacre in English politics, 1624–1632." Albion 30.4 (1998): 583-598.

- Thomas Cogswell, "Prelude to Ré: the Anglo-French struggle over La Rochelle, 1624-1627." History 71.231 (1986): 1-21.

- Palmer-Fernande (2003). Encyclopedia of Religion and War. Taylor & Francis. p. 36. ISBN 9780415942461.

- Timothy Venning, Cromwellian Foreign Policy (1995)

- T.P. Grady, Anglo-Spanish Rivalry in Colonial South-East America, 1650–1725 (Routledge, 2015).

- R. M. Hatton, Louis XIV and Europe (1976).