Thomas Wyatt (poet)

Sir Thomas Wyatt (1503 – 11 October 1542)[1] was a 16th-century English politician, ambassador, and lyric poet credited with introducing the sonnet to English literature. He was born at Allington Castle near Maidstone in Kent, though the family was originally from Yorkshire. His family adopted the Lancastrian side in the Wars of Roses. His mother was Anne Skinner, and his father Henry had been a Privy Councillor of Henry VII and remained a trusted adviser when Henry VIII ascended the throne in 1509. Thomas followed his father to court after his education at St John's College, Cambridge. Entering the King's service, he was entrusted with many important diplomatic missions. In public life his principal patron was Thomas Cromwell, after whose death he was recalled from abroad and imprisoned (1541). Though subsequently acquitted and released, shortly thereafter he died. His poems were circulated at court and may have been published anonymously in the anthology The Court of Venus (earliest edition c.1537) during his lifetime, but were not published under his name until after his death;[2] the first major book to feature and attribute his verse was Tottel's Miscellany (1557), printed 15 years after his death.[3]

Sir Thomas Wyatt | |

|---|---|

.jpg) (Based on a lost drawing by Hans Holbein the Younger) | |

| Born | Thomas Wyatt 1503 Allington Castle, Kent, England |

| Died | 11 October 1542 (aged 38–39) Clifton Maybank House, Dorset, England |

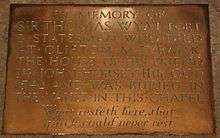

| Resting place | Sherborne Abbey, Dorset |

| Occupation | Politician, Ambassador, Poet |

| Spouse(s) | Elizabeth Brooke |

| Children | Sir Thomas Wyatt the Younger Henry Francis Edward |

| Parent(s) | Sir Henry Wyatt Anne Skinner |

Early life

Thomas Wyatt was born at Allington, Kent in 1503, the son of Sir Henry Wyatt by Anne Skinner, the daughter of John Skinner of Reigate, Surrey.[4] He had a brother Henry, assumed to have died an infant,[5] and a sister Margaret who married Sir Anthony Lee (died 1549) and was the mother of Queen Elizabeth's champion Sir Henry Lee.[6][7]

Education and diplomatic career

Wyatt was over six feet tall, reportedly both handsome and physically strong. He was an ambassador in the service of Henry VIII, but he entered Henry's service in 1515 as "Sewer Extraordinary", and the same year he began studying at St John's College, Cambridge.[8] He accompanied Sir John Russell, 1st Earl of Bedford to Rome to help petition Pope Clement VII to annul Henry VIII's marriage to Catherine of Aragon, freeing him to marry Anne Boleyn. According to some, Wyatt was captured by the armies of Emperor Charles V when they captured Rome and imprisoned the Pope in 1527, but he managed to escape and make it back to England. He was knighted in 1535 and appointed High Sheriff of Kent for 1536.[9] He was elected knight of the shire (MP) for Kent in December 1541.[9]

Marriage and issue

In 1520, Wyatt married Elizabeth Brooke (1503–1550).[10] A year later, they had son Thomas (1521–1554) who led Wyatt's rebellion many years after his father's death.[11] In 1524, Henry VIII assigned Wyatt to be an ambassador at home and abroad, and he separated from his wife soon after on grounds of adultery.[12]

Wyatt's poetry and influence

| Wikisource has original works written by or about: Thomas Wyatt |

Wyatt's professed object was to experiment with the English language, to civilise it, to raise its powers to equal those of other European languages.[13] A significant amount of his literary output consists of translations and imitations of sonnets by Italian poet Petrarch; he also wrote sonnets of his own. He took subject matter from Petrarch's sonnets, but his rhyme schemes are significantly different. Petrarch's sonnets consist of an "octave" rhyming abba abba, followed by a "sestet" with various rhyme schemes. Wyatt employs the Petrarchan octave, but his most common sestet scheme is cddc ee. This marks the beginning of an English contribution to sonnet structure of three quatrains and a closing couplet.[14]

Wyatt experimented in stanza forms including the rondeau, epigrams, terza rima, ottava rima songs, and satires, as well as with monorime, triplets with refrains, quatrains with different length of line and rhyme schemes, quatrains with codas, and the French forms of douzaine and treizaine.[15] He introduced the poulter's measure form, rhyming couplets composed of a 12-syllable iambic line (Alexandrine) followed by a 14-syllable iambic line (fourteener),[16] and he is considered a master of the iambic tetrameter.[17]

Wyatt's poetry reflects classical and Italian models, but he also admired the work of Geoffrey Chaucer, and his vocabulary reflects that of Chaucer; for example, he uses Chaucer's word newfangleness, meaning fickle, in They flee from me that sometime did me seek. Many of his poems deal with the trials of romantic love, and the devotion of the suitor to an unavailable or cruel mistress.[18] Other poems are scathing, satirical indictments of the hypocrisies and pandering required of courtiers who are ambitious to advance at the Tudor court.

Wyatt's poems are short but fairly numerous. His 96 love poems appeared posthumously (1557) in a compendium called Tottel's Misceallany. The most noteworthy are thirty-one sonnets the first in English. Ten of them were translations from Petrarch, while all were written in the Petrarchan form, apart from the couplet ending which Wyatt introduced. serious and reflective in tone, the sonnet shows some stiffness of construction and the metrical uncertainty indicative of difficulty Wyatt found in the new form. Yet their conciseness represents a great advance on the prolixity and uncouthness of much earlier poetry. Wyatt was also responsible for the most important introduction of the personal note into English. Poetry, for, though following his models closely, he wrote of his own experiences. His epigrams, songs and rondeaux are lighter than the sonnets, and they also reveal the care and the elegance that were typical of the new romanticism. His satires are composed in the Italian terza rima, once again showing the direction of the innovating tendencies.

Attribution

The Egerton Manuscript[19] is an album containing Wyatt's personal selection of his poems and translations which preserves 123 texts, partly in his handwriting. Tottel's Miscellany (1557) is the Elizabethan anthology which created Wyatt's posthumous reputation; it ascribes 96 poems to him,[20] 33 not in the Egerton Manuscript. These 156 poems can be ascribed to Wyatt with certainty on the basis of objective evidence. Another 129 poems have been ascribed to him purely on the basis of subjective editorial judgment. They are mostly derived from the Devonshire Manuscript Collection[21] and the Blage manuscript.[22] Rebholz comments in his preface to Sir Thomas Wyatt, The Complete Poems, "The problem of determining which poems Wyatt wrote is as yet unsolved".[23] However, this statement is predicated on his preface's perfunctory rejection of the most significant contribution to its resolution, Richard Harrier's The Canon of Sir Thomas Wyatt's Poetry, which presents an analysis of the documentary evidence establishing a solid case for rejecting 101 of the 129 texts ascribed to Wyatt on no objective basis whatsoever.

Assessment

Critical opinions have varied widely regarding Wyatt's work.[24] Eighteenth century critic Thomas Warton considered Wyatt "confessedly an inferior" to his contemporary Henry Howard, and felt that Wyatt's "genius was of the moral and didactic species" but deemed him "the first polished English satirist".[25] The 20th century saw an awakening in his popularity and a surge in critical attention. C. S. Lewis called him "the father of the Drab Age" (i.e. the unornate), from what he calls the "golden" age of the 16th century.[26] Patricia Thomson describes Wyatt as "the Father of English Poetry".[24]

Rumoured affair with Anne Boleyn

Many have conjectured that Wyatt fell in love with Anne Boleyn in the early- to mid-1520s. Their acquaintance is certain, but it is not certain whether the two shared a romantic relationship. George Gilfillan implies that Wyatt and Boleyn were romantically involved.[27] In his verse, Wyatt calls his mistress Anna and might allude to events in her life:[27]

And now I follow the coals that be quent,

From Dover to Calais against my mind

Gilfillan argues that these lines could refer to Anne's trip to France in 1532 prior to her marriage to Henry VIII[27] and could imply that Wyatt was present, although his name is not included among those who accompanied the royal party to France.[27] Wyatt's sonnet "Whoso List To Hunt" may also allude to Anne's relationship with the King:[27]

Graven in diamonds with letters plain,

There is written her fair neck round about,

"Noli me tangere [Do not touch me], Caesar's, I am".

In still plainer terms, Wyatt's late sonnet "If waker care" describes his first "love" for "Brunette that set our country in a roar" -- clearly Boleyn.

Imprisonment on charges of adultery

In May 1536, Wyatt was imprisoned in the Tower of London for allegedly committing adultery with Anne Boleyn.[28] He was released later that year thanks to his friendship or his father's friendship with Thomas Cromwell, and he returned to his duties. During his stay in the Tower, he may have witnessed Anne Boleyn's execution (19 May 1536) from his cell window, as well as the executions of the five men with whom she was accused of adultery; he wrote a poem which might have been inspired by that experience.[29]

Around 1537, Elizabeth Darrell was his mistress, a former maid of honour to Catherine of Aragon. She bore Wyatt three sons.[30]

By 1540, he was again in the king's favour, as he was granted the site and many of the manorial estates of the dissolved Boxley Abbey. However, he was charged again with treason in 1541; the charges were again lifted, but only thanks to the intervention of Queen Catherine Howard and on the condition of reconciling with his wife. He was granted a full pardon and restored once again to his duties as ambassador. After the execution of Catherine Howard, there were rumours that Wyatt's wife Elizabeth was a possibility to become Henry VIII's next wife, despite the fact that she was still married to Wyatt.[31] He became ill not long after and died on 11 October 1542 around age 39. He is buried in Sherborne Abbey.[32]

Descendants and relatives

Long after Wyatt's death, his only legitimate son Sir Thomas Wyatt the Younger led a thwarted rebellion against Henry's daughter Mary I, for which he was executed. The rebellion's aim was to set the Protestant-minded Elizabeth on the throne, the daughter of Anne Boleyn.[33] His sister Margaret Wyatt was the mother of Henry Lee of Ditchley, from whom descended the Lee family of Virginia, including Robert E. Lee. Wyatt was an ancestor of Wallis Simpson, wife of King Edward VIII, later Duke of Windsor.[34] Thomas Wyatt's great-grandson was Virginia Colony governor Sir Francis Wyatt.[35]

Notes

- Lindsey 1996.

- Huttar 1966

- Shulman 2012, p. 353

- Richardson IV 2011, p. 382; Burrow 2004.

- Burrow 2004.

- Burrow 2004

- Chambers 1936, p. 248.

- "Wyatt, Thomas (WT503T)". A Cambridge Alumni Database. University of Cambridge.

- Miller 1982

- Richardson IV 2011, pp. 381–2.

- Philipot 1898, p. 142

- Shulman 2012, pp. 227–229

- Tillyard 1929.

- The Norton Anthology of English Literature: Sixteenth/Early Seventeenth Century, Volume B, 2012, pg. 647

- Berdan 1931.

- Schmidt 1988.

- Rebholz 1978, p. 45.

- Ward & Trent, eds., et al. Vol. 3 1907–21.

- Egerton Manuscript 2711, British Museum

- Parker 1939, p. 669–677.

- The Devonshire Maunscript Collection of Early Tudor poetry 1532–41, British Museum

- Blage MS, Trinity College, Dublin

- Rebholz 1978, p. 9.

- Thomson 1974.

- Warton 1781.

- Lewis 1954.

- Gilfillan 1858, p. x.

- Warnicke, Retha M. (1989). The Rise and Fall of Anne Boleyn. Cambridge University Press. pp. 64–65. ISBN 9780521370004.

- "Wyatt: V. Innocentia Veritas Viat Fides". Luminarium.org. Retrieved 6 August 2012.

- "A Who'S Who of Tudor Women (D)". Kateemersonhistoricals.com. Archived from the original on 2 June 2012. Retrieved 6 August 2012.

- Hart 2009, p. 197.

- "Sherborne Abbey: The Horsey Tomb". Archived from the original on 8 November 2007. Retrieved 13 July 2008.

- Thomson 1964, p. 273.

- Vickers, Hugo (2011). Behind Closed Doors: The Tragic, Untold, Story of the Duchess of Windsor. London: Hutchinson. p. 377. ISBN 978-0-09-193155-1.

- Bernhard 2004.

References

- Archer, Ian W. "Wyatt, Sir Thomas (b. in or before 1521, d. 1554)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/30112. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Berdan, John Milton (1931), Early Tudor Poetry, 1485–1547, MacMillan

- Bernhard, Virginia (2004), "Wyatt, Sir Francis (1588–1644)'", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press

- Brigden, Susan (2012), Thomas Wyatt: The Heart's Forest, Faber & Faber, ISBN 978-0-571-23584-1

- Burrow, Colin (2004). "Wyatt, Sir Thomas (c.1503–1542)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/30111. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Daalder, Joost, ed (1975), Sir Thomas Wyatt, Collected Poems, London: Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-281155-4CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Gilfillan, George (1858). The Poetical Works of Sir Thomas Wyatt. Edinburgh: James Nichol. Retrieved 5 November 2013.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Harrier, Richard (1975). The Canon of Sir Thomas Wyatt's Poetry. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Huttar, Charles A. (1966). "Wyatt and the Several Editions of 'The Court of Venus'". Studies in Bibliography. 19: 181–195.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lindsey, Karen (1996), Divorced, Beheaded, Survived: Feminist Reinterpretation of the Wives of Henry VIII, Da Capo Press

- Miller, Helen (1982). "WYATT, Sir Thomas I (by 1504–42), of Allington Castle, Kent.". In Bindoff, S. T. (ed.). The History of Parliament: the House of Commons 1509–1558. Members. Historyofparliamentonline.org. Retrieved 20 October 2013.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Parker, William (1939), "The Sonnets in Tottel's Miscellany", PMLA, 54 (3): 669–677, doi:10.2307/458477, JSTOR 458477

- Philipot, John (1898). Hovenden (ed.). The Visitation of Kent, Taken in the Years 1619–1621, (The Publications of the Harleian Society, vol. xlii). London: Harleian Society.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Rebholz, R A, ed (1978), Wyatt:The Complete Poems, London: Penguin Books, ISBN 978-0-14-042227-6CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Shulman, Nicola (2011), Graven With Diamonds: The Many Lives of Thomas Wyatt: Courtier, Poet, Assassin, Spy, Short Books, ISBN 978-1-906021-11-5CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Tillyard, E M W (1929), The Poetry of Sir Thomas Wyatt, A Selection and a Study, London: The Scholartis Press, ISBN 978-0-403-08614-6

- Thomson, Patricia (1964), Sir Thomas Wyatt and His Background, London: Routledge, OCLC 416980380

- Thomson, P (1974), Introduction to Wyatt:The Critical Heritage, London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, ISBN 0-7100-7907-9

External links

- "Archival material relating to Thomas Wyatt". UK National Archives.

- Works by or about Thomas Wyatt at Internet Archive

- Works by Thomas Wyatt at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Life and works

- Modern English translation of "Whoso List to Hunt"

- Portraits of Sir Thomas Wyatt at the National Portrait Gallery, London

- WYATT, Sir Thomas I (by 1504–42), of Allington Castle, Kent. History of Parliament Online