The Man and the Lion

The man and the lion (disputing) is one of Aesop’s Fables and is numbered 284 in the Perry Index.[1] An alternative title is The lion and the statue. The story’s moral is that the source of evidence should be examined before it is accepted.

The fable

A man and a lion dispute which of them is the superior. The man points to a statue of a lion being subdued by a man as his evidence. In the Greek version, the lion retorts that if lions could sculpt, they would show themselves as the victors, drawing the moral that honesty outweighs boasting.[2] In other versions, the lion asks who made the statue and refuses to take it as evidence on learning that it was a man. In the late Latin version of Ademar of Chabannes the lion takes the man to an amphitheatre to demonstrate what happens in reality,[3] while William Caxton has the lion pounce on the man to make its point.[4] But Jefferys Taylor argues facetiously, at the end of his Aesop in Rhyme (1828), that it is the fact that lions cannot sculpt which is the true proof of their inferiority.[5]

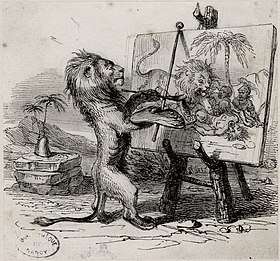

During the Middle Ages some accounts substituted a painting for a statue, and it was following these that Jean de La Fontaine created his Le lion abattu par l'homme (The lion subdued by the man, III.10).[6] There a passing lion retorts to those admiring a hunting scene that if lions could paint the picture would be different. Later illustrators wove whimsical variations on this. Gustave Doré pictured the admirers of a statue in an art gallery in full flight before a bystanding lion. Grandville pictured the lion with artists' implements engaged on his version of the story.[7] Benjamin Rabier's comic publication paired a group of admiring connoisseurs with a pendant of a lion creating his own painting in the desert.[8]

In commenting on the story, Roger L'Estrange pointed out that “’Tis against the rules of common justice for men to be judges in their own case”.[9] A later feminist critique makes the same point,[10] citing Geoffrey Chaucer’s Wyf of Bath, who in defence of her sex demanded “Who peyntede the leoun, tel me who?” and continued the fable’s moral in much the same terms as the lion there.[11]

References

- Aesopica

- Aphthonius, fable 34

- Fable 52

- Fables 4.15

- Fable XXIV

- French text

- Flickr

- Fables de La Fontaine, illustrées par Benjamin Rabier (Paris 1906), p.62

- Fables of Aesop 240

- Lindsay Ann Reid, Ovidian Bibliofictions and the Tudor Book: Metamorphosing Classical Heroines, Routledge 2016, ch.2

- G. A. Rudd, The Complete Critical Guide to Geoffrey Chaucer, Routledge 2001, p.78

External links

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

16th – 19th century Illustrations from books