The Anatomy of Melancholy

The Anatomy of Melancholy (full title: The Anatomy of Melancholy, What it is: With all the Kinds, Causes, Symptomes, Prognostickes, and Several Cures of it. In Three Maine Partitions with their several Sections, Members, and Subsections. Philosophically, Medicinally, Historically, Opened and Cut Up) is a book by Robert Burton, first published in 1621,[1] but republished five more times over the next seventeen years with massive alterations and expansions.

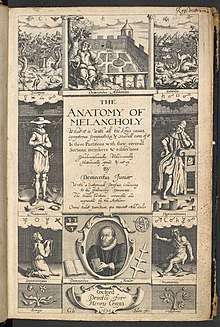

Allegorical frontispiece to the 1628 third edition, engraved by Christian Le Blon. | |

| Author | Robert Burton |

|---|---|

| Country | Britain |

| Language | English |

Publication date | 1621, 1624, 1628, 1632, 1638, and 1651. |

| Media type | |

Overview

On its surface, the book is presented as a medical textbook in which Burton applies his vast and varied learning, in the scholastic manner, to the subject of melancholia (which includes, although it is not limited to, what is now termed clinical depression). Although presented as a medical text, The Anatomy of Melancholy is as much a sui generis work of literature as it is a scientific or philosophical text, and Burton addresses far more than his stated subject. In fact, the Anatomy uses melancholy as the lens through which all human emotion and thought may be scrutinized, and virtually the entire contents of a 17th-century library are marshalled into service of this goal.[2] It is encyclopedic in its range and reference.

In his satirical preface to the reader, Burton's persona and pseudonym "Democritus Junior" explains, "I write of melancholy by being busy to avoid melancholy." This is characteristic of the author's style, which often supersedes the book's strengths as a medical text or historical document as its main source of appeal to admirers. Both satirical and serious in tone, the Anatomy is "vitalized by (Burton's) pervading humour",[3] and Burton's digressive and inclusive style, often verging on a stream of consciousness, consistently informs and animates the text. In addition to the author's techniques, the Anatomy's vast breadth – addressing topics such as digestion, goblins, the geography of America, and others[2] – make it a valuable contribution to multiple research disciplines.

Publication

Burton was an obsessive rewriter of his work and published five revised and expanded editions of The Anatomy of Melancholy during his lifetime. It has often been out of print, most notably between 1676 and 1800.[4] Because no original manuscript of the Anatomy has survived, later reprints have drawn more or less faithfully from the editions published during Burton's life.[5] Early editions are now in the public domain, with several available in their entirety from a number of online sources such as Project Gutenberg. In recent years, increased interest in the book, combined with its status as a public domain work, has resulted in a number of new print editions, most recently a 2001 reprinting of the 1932 edition by The New York Review of Books under its NYRB Classics imprint (ISBN 0-940322-66-8).[2]

Synopsis

Burton defined his subject as follows:

Melancholy, the subject of our present discourse, is either in disposition or in habit. In disposition, is that transitory Melancholy which goes and comes upon every small occasion of sorrow, need, sickness, trouble, fear, grief, passion, or perturbation of the mind, any manner of care, discontent, or thought, which causes anguish, dulness, heaviness and vexation of spirit, any ways opposite to pleasure, mirth, joy, delight, causing forwardness in us, or a dislike. In which equivocal and improper sense, we call him melancholy, that is dull, sad, sour, lumpish, ill-disposed, solitary, any way moved, or displeased. And from these melancholy dispositions no man living is free, no Stoic, none so wise, none so happy, none so patient, so generous, so godly, so divine, that can vindicate himself; so well-composed, but more or less, some time or other, he feels the smart of it. Melancholy in this sense is the character of Mortality... This Melancholy of which we are to treat, is a habit, a serious ailment, a settled humour, as Aurelianus and others call it, not errant, but fixed: and as it was long increasing, so, now being (pleasant or painful) grown to a habit, it will hardly be removed.

In attacking his stated subject, Burton drew from nearly every science of his day, including psychology and physiology, but also astronomy, meteorology, and theology, and even astrology and demonology.

Much of the book consists of quotations[6] from various ancient and medieval medical authorities, beginning with Hippocrates, Aristotle, and Galen. Hence the Anatomy is filled with more or less pertinent references to the works of others. A competent Latinist, Burton also included a great deal of Latin poetry in the Anatomy, and many of his inclusions from ancient sources are left untranslated in the text.

The Anatomy of Melancholy is an especially lengthy book, the first edition being a single quarto volume nearly 900 pages long; subsequent editions were even longer.[7] The text is divided into three major sections plus an introduction, the whole written in Burton's sprawling style. Characteristically, the introduction includes not only an author's note (titled "Democritus Junior to the Reader"), but also a Latin poem ("Democritus Junior to His Book"), a warning to "The Reader Who Employs His Leisure Ill", an abstract of the following text, and another poem explaining the frontispiece. The following three sections proceed in a similarly exhaustive fashion: the first section focuses on the causes and symptoms of "common" melancholies, while the second section deals with cures for melancholy, and the third section explores more complex and esoteric melancholies, including the melancholy of lovers and all varieties of religious melancholies. The Anatomy concludes with an extensive index (which, many years later, The New York Times Book Review called "a readerly pleasure in itself"[8]). Most modern editions include many explanatory notes, and translate most of the Latin.[2]

Critical reception

Admirers of The Anatomy of Melancholy range from Samuel Johnson,[9] Holbrook Jackson (whose Anatomy of Bibliomania [1931] was based on the style and presentation), George Armstrong Custer, Charles Lamb and John Keats (who said it was his favorite book) to Northrop Frye, Stanley Fish, Philip Pullman,[10] Cy Twombly, Jorge Luis Borges (who used a quote as an epigraph to his story "The Library of Babel"), O. Henry (William Sidney Porter), Amalia Lund, William Gass, Nick Cave, Samuel Beckett[11] and Jacques Barzun (who sees in it many anticipations of 20th-century psychiatry).[12] According to The Guardian literary critic Nick Lezard, the Anatomy "survives among the cognoscenti".[13] Washington Irving uses a quote from the book on the title page of The Sketch Book.

Burton's solemn tone and his endeavor to prove indisputable facts by weighty quotations were ridiculed by Laurence Sterne in Tristram Shandy.[14][15] Sterne also mocked Burton's divisions in the titles of his chapters, and parodied his grave and sober account of Cicero's grief for the death of his daughter Tullia.[14]

Notes

- Edwards, M. (2010). "Mad world: Robert Burton's the Anatomy of Melancholy". Brain. 133 (11): 3480–3482. doi:10.1093/brain/awq282.

- Nicholas Lezard (17 August 2001). "The Book to End All Books". The Guardian. Retrieved 20 June 2016.

- Émile Legouis, A History of English Literature (1926)

- The Complete Review discussion of The Anatomy of Melancholy

- William H. Gass, Introduction to The Anatomy of Melancholy, New York Review of Books 2001 ISBN 0-940322-66-8

- "Introduction · the Anatomy of Melancholy · USU Digital Exhibits".

- Nuttall, A. D. (1989-11-23). "Joke Book?". London Review of Books. pp. 18–19.

- Thomas Mallon, The New York Times Book Review, October 3, 1991

- Dunea, G. (2007). "The Anatomy of Melancholy". BMJ : British Medical Journal. 335 (7615): 351.2–351. doi:10.1136/bmj.39301.684363.59. PMC 1949452.

- Pullman, Philip (2005-04-09). "Reasons to be cheerful".

- McCrum, Robert (2017-12-18). "The 100 best nonfiction books: No 98 – the Anatomy of Melancholy by Robert Burton (1621)". The Guardian.

- Jacques Barzun, From Dawn to Decadence, 221-224.

- Nick Lezard, "Classics of the Future", The Guardian, September 16, 2000.

- Ferriar (1798), chapter 3, pp. 55–9, 64.

- Petrie (1970) pp. 261–2.

References

- Ferriar, John (1798) Illustrations of Sterne

- Petrie, Graham (1970) A Rhetorical Topic in "Tristram Shandy", Modern Language Review, Vol. 65, No. 2, April 1970, pp. 261–66

Further reading

- Edward W. Adams (1896). "Robert Burton and the 'Anatomy of Melancholy'," The Gentleman's Magazine, Vol. CCLXXXI, pp. 46–53.

- William Monahan (Fall 2001). "Remedial Reading: The Anatomy of Melancholy by Robert Burton, introduction by William H. Gass". Bookforum. Retrieved 14 April 2007. The introduction by author William H. Gass runs just under 10 pages.

- Mary Ann Lund (2010). "Melancholy, Medicine and Religion in Early Modern England: Reading The Anatomy of Melancholy". Cambridge University Press.

- Susan Wells (2019). Robert Burton's Rhetoric: An Anatomy of Early Modern Knowledge. Pennsylvania State University Press.

External links

Online editions

- The 1638 edition on Google Books

- The Anatomy of Melancholy at Project Gutenberg

- The Anatomy of Melancholy Online reading and multiple ebook formats at Ex-classics

- The Anatomy of Melancholy at Making of America

- The Anatomy of Melancholy at PsyPlexus

- The Anatomy of Melancholy at Internet Archive – scan of 1896 edition

- The Anatomy of Melancholy Librivox audio recording (public domain)

Discussions of the book

- "The Anatomy of Melancholy" – BBC Radio 4 In Our Time programme about the book.

- The Complete Review discussion of The Anatomy of Melancholy