Tamga

A tamga or tamgha (Old Turkic: 𐱃𐰢𐰍𐰀, Turkish: damga, Ottoman Turkish: طمغا, Azerbaijani: damğa; "stamp, seal") is an abstract seal or stamp used by Eurasian nomadic peoples and by cultures influenced by them. The tamga was normally the emblem of a particular tribe, clan or family. They were common among the Eurasian nomads throughout Classical Antiquity and the Middle Ages (including Iranians (Alans, Sarmatians, Scythians), Mongols and Turkic peoples.

- For the prehistoric organism, see Tamga (genus)

Similar "tamga-like" symbols were sometimes adopted by sedentary peoples adjacent to the Pontic-Caspian steppe both in Eastern Europe and Central Asia.[1][2][3][4] Archaeologists prize tamgas as a first-rate source for the study of present and extinct cultures.

Medieval tamgas

Mongol empire

Since the time when the ancients, including the Mongol nations have developed into relative groups, origins, and ethnic groups, the symbol and belief of a clan have emerged, and a custom to distinguish their origins and relatives have been established. Consequently, when labor distributions within clans began to develop and people started to manage an economy, various tamgas, drawings, notes and earmarks have been used as an identification sign for labor instruments and utilities as well as in domestication of animals. Every time the clan branched off due to internal clashes, the number of derivative tamghas gradually developed into personal, family, lineage, khans, and state tamghas. Those new tamghas were created through adding new markings on the original tamgha, in order to conserve the tradition. In the Mongol Empire a Tamgha was a seal placed on taxed items, and by extension, a tax on commerce (and see Eastern Europe below).[5]

"Tamga" or "tamag" literally means a stamp or seal in the Mongolian language. Tamgas are also stamped using hot irons on domesticated animals such as horses in present-day Mongolia and others to identify that the livestock belongs to a certain family while they graze during the day on their own. In this regard, each family has their own tamga markings for easier identification. Tamga marking in that case is not very elaborate and is just a curved iron differentiating from other families' tamgas. The President of Mongolia also passes the tamag "state seal" when he or she transitions the position to the new president. In the presidential case, the tamag or seal is a little more elaborate and is contained in a wooden box.

Turkic peoples

.jpg)

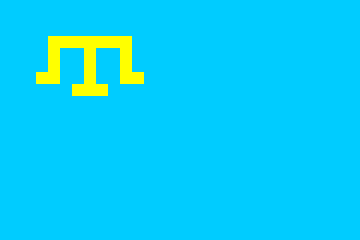

The Turks who remained pastoral nomad kings in eastern Anatolia and Iran however, continued to use their clan tamgas, and in fact they became high-strung nationalistic imagery. The Ak Koyunlu and Kara Koyunlu, like many other royal dynasties in Eurasia, put their tamga on their flags and stamped their coinage with it.

For those Turks who never left their homeland of Turkestan in the first place it remained and still is what it was originally, a cattle brand and clan identifier.

Among modern Turkic peoples, the tamga is a design identifying property or cattle belonging to a specific Turkic clan, usually as a cattle brand or stamp.

When Turkish clans took over more urban or rural areas, tamgas dropped out of use as pastoral ways of life became forgotten. This is most evident in the Turkish clans who took over western and eastern Anatolia following the Battle of Manzikert. The Turks who took over western Anatolia founded the Sultanate of Rûm and became Roman-style aristocrats. Most of them adopted the (at the time) Muslim symbol of the Seal of Solomon after the Sultanate disintegrated into a mass of feuding ghazi states (see Isfendiyarids, Karamanids). Only the Ottoman ghazi state (later to become the Ottoman Empire) kept its tamga, and this was highly stylized, so much so that the bow was stylized down eventually to a crescent moon.

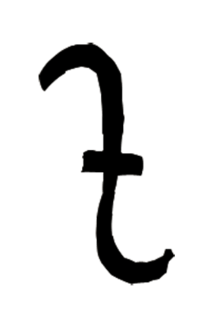

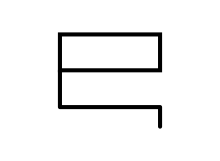

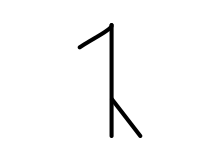

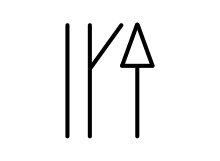

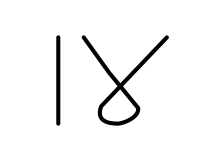

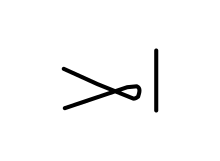

Tamgas of the twenty-one Oghuz tribes (as Charuklug had none) according to Mahmud al-Kashgari in Dīwānu l-Luġat al-Turk:[6]

Kınık

Kınık Kayı

Kayı

Iwa (Yiwa)

Iwa (Yiwa) Salur

Salur Afshar

Afshar

Bugduz

Bugduz Bayat

Bayat Yazigir

Yazigir

Karaboluk

Karaboluk Аlkaboluk

Аlkaboluk

Uregir (Yüregir)

Uregir (Yüregir) Tutirka

Tutirka

Döger

Döger

Chepni

Chepni Charuklug

Charuklug

Eastern Europe

In Russia, the term tamga (тамга) survived in state institution of border customs, with associated cluster of terms: tamozhnya (таможня, customs), tamozhennik (таможенник, customs officer), rastamozhit' (растаможить, pay customs duties), derived from the use of tamga as a certificate of state.

- Tamga of the Bosporan king Tiberius Julius Eupator, crowned by two winged victories. The relief dates to the second century CE.

Example for Rurikid Trident

Example for Rurikid Trident

Islamic empires

In the late medieval Turco-Mongol states, the term tamga was used for any kind of official stamp or seal. This usage persisted in the early modern Islamic Empires (Ottoman Empire, Mughal Empire), and in some of their modern successor states.

In the Urdu language (which absorbed Turkic vocabulary), Tamgha is used as medal. Tamgha-i-Jurat is the fourth highest Military medal of Pakistan. It is admissible to all ranks for gallantry and distinguished services in combat. Tamgha-i-Imtiaz or Tamgha-e-Imtiaz (Urdu: تمغہ امتیاز), which translates as "medal of excellence", is fourth highest honour given by the Government of Pakistan to both the military and civilians. Tamgha-i-Khidmat or Tamgha-e-Khidmat (Urdu: تمغۂ خدمت), which translates as "medal of services", is seventh highest honour given by the Government of Pakistan to both the military and civilians. It is admissible to non-commissioned officers and other ranks for long meritorious or distinguished services of a non-operational nature.

In Egypt, the term damgha (Arabic: دمغة) or tamgha (تمغة) is still used in two contexts. One is a tax or fee when dealing with the government. It is normally in the form of stamps that have to be purchased and affixed to government forms, such as a driver license or a registration deed for a contract. The term is derived from the Ottoman damga resmi. Another is a stamp put on every piece of jewelry made from gold or silver to indicate it is genuine, and not made of baser metals.

See also

Notes

- Neubecker, Ottfried (2002). Heraldik (in German). Orbis. ISBN 3-572-01344-5.

- Brook, Kevin Alan (2006). The Jews of Khazaria (2nd ed.). Rowman and Littlefield. p. 154. ISBN 0-7425-4981-X.

- Franklin, Simon; Shepard, Jonathan (1996). The Emergence of Rus 750–1200. London: Longman. pp. 120–121.

- Pritsak, Omeljan (1998). The Origins of the Old Rus' Weights and Monetary Systems. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Ukrainian Research Institute. pp. 78–79. ISBN 0-582-49090-1.

- Christian, David (1999). A History of Russia, Mongolia and Central Asia. Blackwell. p. 415.

- Mahmûd, Kâşgarlı. Divânü Lugâti't-Türk. Kabalcı Yayınevi. p. 354.

References

- Yatsenko, S. A. (2001). Знаки-тамги ираноязычных народов древности и раннего средневековья [Tamga-signs of Iranic-speaking peoples of antiquity and the early medieval period]. Moscow: Восточная литература. ISBN 5-02-018212-5.

- Paksoy, H. B. (June 2004). "Identity Markers: Uran, Tamga, Dastan". Transoxiana. 8.

- Fetisov, A. (2007). Translated by Galkova, I. "The "Rurikid sign" from the B3 church at Basarabi-Murfatlar" (PDF). Studia Patzinaka. 4 (1): 29–44.

- "Online Ottoman Turkish Dictionary".