Syncopation

In music, syncopation involves a variety of rhythms played together to make a piece of music, making part or all of a tune or piece of music off-beat. More simply, syncopation is "a disturbance or interruption of the regular flow of rhythm": a "placement of rhythmic stresses or accents where they wouldn't normally occur".[1] It is the correlation of at least two sets of time intervals.[2]

Syncopation is used in many musical styles, especially dance music: "All dance music makes use of syncopation, and it's often a vital element that helps tie the whole track together".[3] In the form of a back beat, syncopation is used in virtually all contemporary popular music.

Syncopation can also occur when a strong harmony is placed on a weak beat, for instance, when a 7th-chord is placed on the second beat of 3

4 measure or a dominant chord is placed at the fourth beat of a 4

4 measure. The latter frequently occurs in tonal cadences in 18th- and early-19th-century music and is the usual conclusion of any section.

A hemiola can also be seen as one straight measure in three with one long chord and one short chord and a syncope in the measure thereafter, with one short chord and one long chord. Usually, the last chord in a hemiola is a (bi-)dominant, and as such a strong harmony on a weak beat, hence a syncope.

Types of syncopation

Technically, "syncopation occurs when a temporary displacement of the regular metrical accent occurs, causing the emphasis to shift from a strong accent to a weak accent".[4] "Syncopation is", however, "very simply, a deliberate disruption of the two- or three-beat stress pattern, most often by stressing an off-beat, or a note that is not on the beat."[5]

Suspension

In the following example, there are two points of syncopation where the third beats are carried over (sustained) from the second beats. In the same way, the first beat of the second bar is carried over from the fourth beat of the first bar.

Though syncopation may be highly complex, dense or complex-looking rhythms often contain no syncopation. The following rhythm, though dense, stresses the regular downbeats, 1 and 4 (in 6

8):[5]

However, whether it's a placed rest or an accented note, any point in a piece of music that moves the listener's sense of the downbeat is a point of syncopation because it's shifting where the strong and weak accents are built.[5]

Off-beat syncopation

The stress can shift by less than a whole beat, so it falls on an offbeat, as in the following example, where the stress in the first bar is shifted back by an eighth note (or quaver):

Whereas the notes are expected to fall on the beat:

Playing a note ever so slightly before, or after, a beat is another form of syncopation because this produces an unexpected accent:

It can be helpful to think of a 4

4 rhythm in eighth notes and count it as "1-and-2-and-3-and-4-and". In general, emphasizing the "and" would be considered the off-beat.

Anticipated bass

Anticipated bass[6] is a bass tone that comes syncopated shortly before the downbeat, which is used in Son montuno Cuban dance music. Timing can vary, but it usually falls on the 2+ and the 4 of the 4

4 time, thus anticipating the third and first beats. This pattern is commonly known as the Afro-Cuban bass tumbao.

Transformation

Richard Middleton[7] suggests adding the concept of transformation to Narmour's[8] prosodic rules which create rhythmic successions in order to explain or generate syncopations. "The syncopated pattern is heard 'with reference to', 'in light of', as a remapping of, its partner." He gives examples of various types of syncopation: Latin, backbeat, and before-the-beat. First however, one may listen to the audio example of stress on the "strong" beats, where expected: ![]()

Latin equivalent of simple 4

4

4

In the example below, the first two measures has an unsyncopated rhythm is shown in the first measure The third measure has a syncopated rhythm in which the first and fourth beat are provided as expected, but the accent unexpectedly lands in between the second and third beats, creating a familiar "Latin rhythm" known as tresillo.

Backbeat transformation of simple 4

4

4

The accent may be shifted from the first to the second beat in duple meter (and the third to fourth in quadruple), creating the backbeat rhythm:

Different crowds will "clap along" at concerts either on 1 and 3 or on 2 and 4, as above.

"Satisfaction" example

The phrasing of "Satisfaction" is a good example of syncopation.[5] It is derived here from its theoretic unsyncopated form, a repeated trochee (¯ ˘ ¯ ˘). A backbeat transformation is applied to "I" and "can't", and then a before-the-beat transformation is applied to "can't" and "no".[7]

1 & 2 & 3 & 4 & 1 & 2 & 3 & 4 &

Repeated trochee: ¯ ˘ ¯ ˘

I can't get no – o

Backbeat trans.: ¯ ˘ ¯ ˘

I can't get no – o

Before-the-beat: ¯ ˘ ¯ ˘

I can't get no – o

This demonstrates how each syncopated pattern may be heard as a remapping, "with reference to" or "in light of", an unsyncopated pattern.[7]

History

Syncopation has been an important element of European musical composition since at least the Middle Ages. Many Italian and French compositions of the music of the 14th-century Trecento make use of syncopation, as in of the following madrigal by Giovanni da Firenze. (See also hocket.)

The refrain "Deo Gratias" from the 15th-century anonymous English Agincourt Carol is also characterised by lively syncopation:

“The 15th-century carol repertory is one of the most substantial monuments of English medieval music... The early carols are rhythmically straightforward, in modern 6/8 time; later the basic rhythm is in 3/4, with many cross-rhythms... as in the famous Agincourt carol 'Deo gratias Anglia'. As in other music of the period, the emphasis is not on harmony, but on melody and rhythm.”[9]

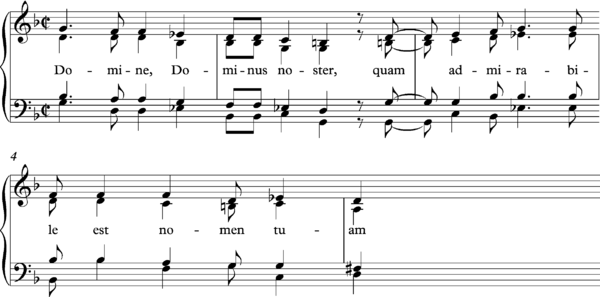

Composers of the musical High Renaissance Venetian School, such as Giovanni Gabrieli (1557–1612), exploited syncopation in both their secular madrigals and instrumental pieces and also in their choral sacred works, such as the motet Domine, Dominus noster:

Denis Arnold (1979, p. 93) says: "the syncopations of this passage are of a kind which is almost a Gabrieli fingerprint, and they are typical of a general liveliness of rhythm common to Venetian music".[10] The composer Igor Stravinsky (1959, p. 91), no stranger to syncopation himself, spoke of "those marvellous rhythmic inventions" that feature in Gabrieli's music.[11]

J. S. Bach and Handel used syncopated rhythms as an inherent part of their compositions. One of the best-known examples of syncopation in music from the Baroque era was the "Hornpipe" from Handel’s Water Music (1733).

Christopher Hogwood (2005, p. 37) describes the Hornpipe as “possibly the most memorable movement in the collection, combining instrumental brilliance and rhythmic vitality… Woven amongst the running quavers are the insistent off-beat syncopations that symbolise confidence for Handel.”[12] Bach's Brandenburg Concerto No. 4 features striking deviations from the established rhythmic norm in its first and third movements. According to Malcolm Boyd (1993, p. 53), each ritornello section of the first movement, "is clinched with an Epilog of syncopated antiphony":[13]

Boyd (1993, p. 85) also hears the coda to the third movement as "remarkable… for the way the rhythm of the initial phrase of the fugue subject is expressed… with the accent thrown on to the second of the two minims (now staccato)":[13]

Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven, and Schubert used syncopation to create variety especially in their symphonies. The opening movement of Beethoven's Eroica Symphony No. 3 exemplifies powerfully the uses of syncopation in a piece in triple time. After setting up a clear pattern of three beats to a bar at the outset, Beethoven disrupts it through syncopation in a number of ways:

(1) By displacing the rhythmic emphasis to a weak part of the beat, as in the first violin part in bars 7–9:

Taruskin (2010, p. 658) describes here how "the first violins, entering immediately after the C sharp, are made palpably to totter for two bars".[14]

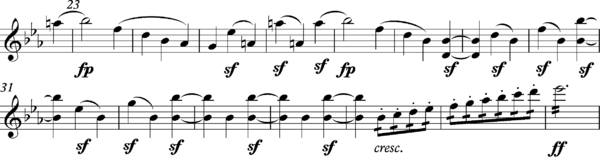

(2) By placing accents on normally weak beats, as in bars 25–26 and 28–35:

This "long sequence of syncopated sforzandi"[14] recurs later during the development section of this movement, in a passage that Antony Hopkins (1981, p. 75) describes as "a rhythmic pattern that rides roughshod over the properties of a normal three-in-a bar".[15]

(3) By inserting silences (rests) at points where a listener might expect strong beats, in the words of George Grove (1896, p. 61), "nine bars of discords given fortissimo on the weak beats of the bar":[16]

See also

- Anacrusis

- Counting (music)

- Syncopation (dance)

- Syncope and epenthesis, analogous linguistic concepts where vocal rhythm causes the loss or addition of sounds to a word

- Hemiola

- Cross-beat

- Nu metal, a subgenre of heavy metal music created in the 1990s, utilising syncopated rhythms.

References

- Hoffman, Miles (1997). "Syncopation". National Symphony Orchestra. NPR. Retrieved 13 July 2009.

- Patterson, William Morrison, "Rhythm of Prose" (Introductory Outline), Columbia University Press 1917.

- Snoman, Rick (2004). Dance Music Manual: Toys, Tools, and Techniques. p. 44. ISBN 0-240-51915-9.

- Reed, Ted (1997). Progressive Steps to Syncopation for the Modern Drummer, p. 33. ISBN 0-88284-795-3.

- Day, Holly and Pilhofer, Michael (2007). Music Theory For Dummies, p. 58–60. ISBN 0-7645-7838-3.

- Peter Manuel (1985). "The anticipated bass in Cuban popular music", Latin American Music Review, Vol. 6, No. 2, Autumn-Winter, pp. 249–261.

- Middleton (1990/2002). Studying Popular Music, p.212-13. Philadelphia: Open University Press. ISBN 0-335-15275-9.

- Narmour (1980). p.147-53. Cited in Middleton (1990/2002), p.212-13.

- https://www.britannica.com/art/carol, accessed 14 March 2019.

- Arnold, D. (1979) Giovanni Gabrieli. Oxford University Press.

- Stravinsky, I. and Craft, R. (1959) Conversations with Igor Stravinsky. London, Faber.

- Hogwood, C. (2005) Handel: Water Music and Music for the Royal Fireworks. Cambridge University press.

- Boyd, M. (1993) Bach: The Brandenburg Concertos. Cambridge University Press.

- Taruskin, R. (2010), The Oxford History of Western Music. Oxford University Press.

- Hopkins, A. (1981) The Nine Symphonies of Beethoven. London, Heinemann.

- Grove, G. (1896) Beethoven and his Nine Symphonies. London, Novello, 1896.

Sources

- Seyer, Philip, Allan B. Novick and Paul Harmon (1997). What Makes Music Work. Forest Hill Music. ISBN 0-9651344-0-7.