Svalbard Treaty

The Svalbard Treaty (originally the Spitsbergen Treaty) recognises the sovereignty of Norway over the Arctic archipelago of Svalbard, at the time called Spitsbergen. The exercise of sovereignty is, however, subject to certain stipulations, and not all Norwegian law applies. The treaty regulates the demilitarisation of the archipelago. The signatories were given equal rights to engage in commercial activities (mainly coal mining) on the islands. As of 2012, Norway and Russia are making use of this right.

Long name:

| |

|---|---|

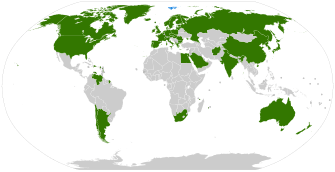

Ratifications of the treaty | |

| Signed | 9 February 1920 |

| Location | Paris, France |

| Effective | 14 August 1925 |

| Condition | Ratification by all the signatory powers |

| Parties | 46[1] - See list |

| Depositary | Government of the French Republic |

| Languages | French and English |

Uniquely, the archipelago is an entirely visa-free zone under the terms of the Svalbard Treaty.[2]

The treaty was signed on 9 February 1920 and submitted for registration in the League of Nations Treaty Series on 21 October 1920.[3] There were 14 original High Contracting Parties: Denmark, France, Italy, Japan, the Netherlands,[4] Norway, Sweden, the United Kingdom (including the dominions of Australia, Canada, New Zealand and South Africa, as well as India), and the United States.[5] Of the original signatories, Japan was the last to ratify the treaty on 2 April 1925, and the treaty came into force on 14 August 1925.[6]

Many additional nations acceded to the treaty after it was ratified by the original signatories, including several before it came into force. As of 2018, there are 46 parties to the treaty.[1]

Name of the treaty

The original treaty is entitled the Treaty recognising the sovereignty of Norway over the Archipelago of Spitsbergen. It refers to the entire archipelago as "Spitsbergen", which had been the only name in common usage since 1596 (with minor variations in spelling). In 1925, five years after the conclusion of the treaty, the Norwegian authorities proceeded to officially rename the islands "Svalbard". This new name was a modern adaptation of the ancient toponym Svalbarði, attested in the Norse sagas as early as 1194. The exonym "Spitsbergen" subsequently came to be applied to the main island in the archipelago. Accordingly, in modern historiography the Treaty of Spitsbergen is commonly referred to anachronistically as the Svalbard Treaty to reflect the name change.[7][8]

History

The archipelago was discovered by the Dutch explorer Willem Barentsz in 1596.[9] It was named Spitsbergen, meaning "sharp-peaked mountains" (literally "spit-bergs"). It was uninhabited.[10] The islands were renamed in the 1920s by Norway as Svalbard.[11]

Spitsbergen/Svalbard began as a territory free of a nation, with people from different countries participating in industries including fishing, whaling, mining, research and later, tourism. Not belonging to any nation left Svalbard largely free of regulations or laws, though there were conflicts over the area due to whaling rights and sovereignty disputes between England, the Netherlands and Denmark–Norway in the first half of the 17th century.[12] By the 20th century mineral deposits were found on the main island and continual conflicts between miners and owners created a need for a government.[13]

Contents

The Spitsbergen Treaty was signed in Paris on 9 February 1920, during the Versailles negotiations after World War I. In this treaty, international diplomacy recognized Norwegian sovereignty (the Norwegian administration went in effect by 1925) and other principles relating to Svalbard. This includes:[5]

- Svalbard is part of Norway: Svalbard is completely controlled by and forms part of the Kingdom of Norway. However, Norway's power over Svalbard is restricted by the limitations listed below:

- Taxation: This allows taxes to be collected, but only enough to support Svalbard and the Svalbard government. This results in lower taxes than mainland Norway and the exclusion of any taxes on Svalbard supporting Norway directly. Also, Svalbard's revenues and expenses are separately budgeted from mainland Norway.

- Environmental conservation: Norway must respect and preserve the Svalbard environment.

- Non-discrimination: All citizens and all companies of every nation under the treaty are allowed to become residents and to have access to Svalbard including the right to fish, hunt or undertake any kind of maritime, industrial, mining or trade activity. The residents of Svalbard must follow Norwegian law, though Norwegian authority cannot discriminate against or favor any residents of any given nationality.

- Military restrictions: Article 9 prohibits naval bases and fortifications and also the use of Svalbard for war-like purposes. It is not, however, entirely demilitarized.

Disputes regarding natural resources

200-nautical-mile (370 km) zone around Svalbard

There has been a long-running dispute, primarily between Norway and Russia (and before it, the Soviet Union) over fishing rights in the region.[14][15] In 1977, Norway established a regulated fishery in a 200-nautical-mile (370 km) zone around Svalbard (though it did not close the zone to foreign access).[14] Norway argues that the treaty's provisions of equal economic access apply only to the islands and their territorial waters (4 nautical miles at the time) but not to the wider exclusive economic zone. In addition, it argues that the continental shelf is a part of mainland Norway's continental shelf and should be governed by the 1958 Continental Shelf Convention.[15] The Soviet Union/Russia disputed and continues to dispute this position and consider the Spitsbergen Treaty to apply to the entire zone. Talks were held in 1978 in Moscow but did not resolve the issue.[14] Finland and Canada support Norway's position, while most of the other treaty signatories have expressed no official position.[14] The relevant parts of the treaty are as follows:

Ships and nationals of all the High Contracting Parties shall enjoy equally the rights of fishing and hunting in the territories specified in Article 1 and in their territorial waters. (from Article 2)

They shall be admitted under the same conditions of equality to the exercise and practice of all maritime, industrial, mining or commercial enterprises both on land and in the territorial waters, and no monopoly shall be established on any account or for any enterprise whatever. (from Article 3)

Natural resources outside the 200-nautical-mile (370 km) zone

"Mainly the dispute is about whether the Svalbard Treaty also is in effect outside the 12-nautical-mile territorial sea," according to Norway's largest newspaper, Aftenposten.[16] If the treaty comes into effect outside the zone, then Norway will not be able to claim the full 78% of profits of oil- and gas harvesting, said Aftenposten in 2011.[17]

Parties

A list of parties is shown below; the dates below reflect when a nation deposited its instrument of ratification or accession.[1][18] Some parties are successor states to the countries that joined the treaty, as noted below.

| Country | Date of ratification | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Afghanistan | 23 November 1929 | |

| Albania | 29 April 1930 | |

| Argentina | 6 May 1927 | |

| Australia | 29 December 1923 | Extension by the United Kingdom. |

| Austria | 12 March 1930 | |

| Belgium | 27 May 1925 | |

| Bulgaria | 20 October 1925 | |

| Canada | 29 December 1923 | Extension by the United Kingdom. |

| Chile | 17 December 1928 | |

| China | 1 July 1925 | Acceded as the Republic of China. Both the People's Republic of China and the Republic of China claim to be the successor or continuing state, but as of 2018 all other parties to the treaty recognize only the People's Republic of China. |

| Czech Republic | 21 June 2006 | Czechoslovakia acceded to the treaty on 9 July 1930. On 21 June 2006, the Czech Republic informed that it considered itself bound to the treaty since its independence on 1 January 1993, as a successor state. |

| Denmark | 24 January 1924 | Extension to the entire Danish Realm. |

| Dominican Republic | 3 February 1927 | |

| Egypt | 13 September 1925 | |

| Estonia | 7 April 1930 | |

| Finland | 12 August 1925 | |

| France | 6 September 1924 | |

| Germany | 16 November 1925 | Acceded as the Weimar Republic. On 21 October 1974, East Germany informed that it also reapplied the treaty since 7 August 1974. East Germany reunited with West Germany in 1990. |

| Greece | 21 October 1925 | |

| Hungary | 29 October 1927 | |

| Iceland | 31 May 1994 | |

| India | 29 December 1923 | Extension by the United Kingdom. |

| Ireland | 29 December 1923 | Ireland was part of the United Kingdom when the latter signed the treaty, but most of Ireland left the United Kingdom and formed the Irish Free State before the treaty was ratified. On 15 April 1976, Ireland informed that it also applied the treaty since its ratification by the United Kingdom. |

| Italy | 6 August 1924 | |

| Japan | 2 April 1925 | |

| Latvia | 13 June 2016 | |

| Lithuania | 22 January 2013 | |

| Monaco | 22 June 1925 | |

| Netherlands | 3 September 1920 | Extension to the entire Kingdom of the Netherlands. |

| New Zealand | 29 December 1923 | Extension by the United Kingdom. |

| North Korea | 16 March 2016 | |

| Norway | 8 October 1924 | |

| Poland | 2 September 1931 | |

| Portugal | 24 October 1927 | |

| Romania | 10 July 1925 | |

| Russia | 7 May 1935 | Acceded as the Soviet Union. On 27 January 1992, Russia declared that it continued to apply the treaties concluded by the Soviet Union. |

| Saudi Arabia | 2 September 1925 | Acceded as the Kingdom of Hejaz. |

| Slovakia | 21 February 2017 | Czechoslovakia acceded to the treaty on 9 July 1930. On 21 February 2017, Slovakia informed that it considered itself bound to the treaty since its independence on 1 January 1993, as a successor state. |

| South Africa | 29 December 1923 | Extension by the United Kingdom. |

| South Korea | 11 September 2012 | |

| Spain | 12 November 1925 | |

| Sweden | 15 September 1924 | |

| Switzerland | 30 June 1925 | |

| United Kingdom | 29 December 1923 | Extension to Australia, Canada, India, New Zealand and South Africa. Ireland also applied the treaty since its ratification by the United Kingdom. |

| United States | 2 April 1924 | |

| Venezuela | 8 February 1928 |

Yugoslavia also acceded to the treaty on 6 July 1925, but, as of 2018, none of its successor states have declared to continue application of the treaty.

See also

References

Notes

- "Treaties and agreements of France" (in French). Ministry of Foreign Affairs of France (depositary country). Retrieved 19 February 2019.

- Immigrants warmly welcomed, Al Jazeera, 4 July 2006.

- League of Nations Treaty Series, vol. 2, pp. 8–19

- On Dutch interest and historical claims see Muller, Hendrik, ‘Nederland's historische rechten op Spitsbergen’, Tijdschrift van het Koninklijk Nederlandsch Aardrijkskundig Genootschap 2e serie, deel 34 (1919) no. 1, 94–104.

- Original Spitsbergen Treaty

- Spitsbergen Treaty and Ratification (in Norwegian)

- "Norwegian place names in polar regions". Norwegian Polar Institute.

- "History – Spitsbergen – Svalbard". spitsbergen-svalbard.com.

- Grydehøj, Adam (15 November 2019), "Svalbard: International Relations in an Exceptionally International Territory", The Palgrave Handbook of Arctic Policy and Politics, Springer International Publishing, pp. 267–282, ISBN 978-3-030-20556-0, retrieved 13 May 2020 Alt URL

- Torkildsen, Torbjørn; et al. (1984). Svalbard: vårt nordligste Norge (in Norwegian). Oslo: Forlaget Det Beste. p. 30. ISBN 82-7010-167-2.

- Umbreit, Andreas (2005). Guide to Spitsbergen. Bucks: Bradt. pp. XI–XII. ISBN 1-84162-092-0.

- Torkildsen (1984), pp. 34–36

- Arlov, Thor B. (1996). Svalbards historie (in Norwegian). Oslo: Aschehoug. pp. 249, 261, 273. ISBN 82-03-22171-8.

- Alex G. Oude Elferink (1994). The Law of Maritime Boundary Delimitation: A Case Study of the Russian Federation. Martinus Nijhoff. pp. 230–231.

- Willy Østreng (1986). "Norway in Northern Waters". In Clive Archer & David Scrivener (ed.). Northern Waters: Security and Resource Issues. Routledge. pp. 165–167.

- Aftenposten, "USA snuser på Svalbard-olje" by Torbjørn Pedersen, page 14

- Aftenposten, "USA snuser på Svalbard-olje" by Torbjørn Pedersen

- "Treaty concerning the Archipelago of Spitsbergen, including Bear Island". Government of the Netherlands. Retrieved 19 February 2019.

Literature

- Moe, Arild; Schei, Peter Johan (18 November 2005). "The High North – Challenges and Potentials" (PDF). Prepared for French-Norwegian Seminar at IFRI, Paris, 24 November 2005. Fridtjof Nansen Institute (www.fni.no). Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 December 2008. Retrieved 11 August 2008. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help)

External links

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- Treaty between Norway, The United States of America, Denmark, France, Italy, Japan, the Netherlands, Great Britain and Ireland and the British overseas Dominions and Sweden concerning Spitsbergen signed in Paris 9th February 1920.

- Treaty Concerning the Archipelago of Spitsbergen

- Svalbard Treaty and Ratification (in Norwegian)

- Svalbard – an important arena – Speech by Norwegian Minister of Foreign Affairs, 15 April 2006.