Sustainable fashion

Sustainable fashion is a movement and process of fostering change to fashion products and the fashion system towards greater ecological integrity and social justice. Sustainable fashion concerns more than addressing fashion textiles or products. It comprises addressing the whole system of fashion. This means dealing with interdependent social, cultural, ecological and financial systems.[1] It also means considering fashion from the perspective of many stakeholders - users and producers, all living species, contemporary and future dwellers on earth. Sustainable fashion therefore belongs to, and is the responsibility of, citizens, public sector and private sector. A key example of the need for systems thinking[2] in fashion is that the benefits of product-level initiatives, such as replacing one fiber type for a less environmentally harmful option, is eaten up by increasing volumes of fashion products. An adjacent term to sustainable fashion is eco fashion.

Introduction

Background

The origins of the sustainable fashion movement are intertwined with those of the modern environmental movement, of which it is a part, and specifically the publication in 1962 of the book Silent Spring by American biologist Rachel Carson.[3] Carson's book exposed the serious and widespread pollution associated with the use of agricultural chemicals, a theme that is still important in the debate around the environmental and social impact of fashion today. The decades which followed saw the impact of human actions on the environment to be more systematically investigated, including the effects of industrial activity, and to new concepts for mitigating these effects, notably sustainable development, a term coined in 1987 by the Brundtland Report.[4]

In the early 1990s and roughly coinciding with the United Nations conference on Environment and Development in 1992, popularly known as the Rio Earth Summit, 'green issues' (as they were called at the time) made their way into fashion and textiles publications.[5][6] Typically these publications featured the work of well-known companies such as Patagonia and ESPRIT, who in the late 1980s brought environmental concerns into their businesses. The owners of those companies at that time, Yvon Chouinard and Doug Tompkins, were outdoorsmen and witnessed the environment being harmed by over production and over consumption of material goods. They commissioned research into the impacts of fibers used in their companies. For Patagonia, this resulted in a lifecycle assessment for four fibers, cotton, wool, nylon and polyester. For ESPRIT the focus was on cotton—and finding better alternatives to it—which represented 90% of their business at that time. Interestingly, a similar focus on materials impact and selection is still the norm in the sustainable fashion thirty years on.[1]

The principles of 'green' or 'eco' fashion, as put forward by these two companies, was based on the philosophy of the deep ecologists Arne Næss, Fritjof Capra, and Ernest Callenbach, and design theorist Victor Papanek.[7] This imperative is also reliant on feminist understanding of human-nature relationships, interconnectedness and “ethics of care” as advocated by Carolyn Merchant,[8] Suzi Gablik,[9] Vandana Shiva,[10] and Carol Gilligan.[11] The legacy of the early work of Patagonia and ESPRIT continues to shape the fashion industry agenda around sustainability today. They co-funded the first organic cotton conference held in 1991 in Visalia, California. And in 1992, the ESPRIT ecollection, developed by head designer Lynda Grose,[12] was launched at retail and it was based on the Eco Audit Guide, published by the Elmwood Institute. Throughout the 1990s and early 2000s, the movement in sustainable fashion broadened to include many brands. Though the primary focus has remained on improving the impacts of products through fiber and fabric processing and material provenance, Doug Tompkins and Yvon Chouinard were early to note the fundamental cause of unsustainability: exponential growth and consumption.[13] ESPRIT placed an ad in Utne Reader in 1990 making a plea for responsible consumption. In 2011 the brand Patagonia ran an ad and a PR campaign "Don't buy this jacket" with a picture of Patagonia merchandise. This message was intended to encourage people to consider the effect that consumption has on the environment, and to purchase only what they need.

In parallel with the industry agenda, a research agenda around sustainable fashion has been in development since the early 1990s, with the field now having its own history, dynamics, politics, practices, sub-movements and evolution of analytical and critical language.[14][15][16][17][18][19] The field is broad in scope and includes technical projects that seek to improve the resource efficiency of existing operations,[20] the work of brands and designers to work within current priorities[21] as well as those which look to fundamentally reimagine the fashion system differently, including the growth logic.[22] In 2019, a group of researchers formed the Union for Concerned Researchers in Fashion to advocate for radical and co-ordinated research activity commensurate with the challenges of biodiversity loss and climate change.[23] In the fall of 2019, the UCRF received the North Star Award at the Green Carpet Fashion Awards, an organization focused on the promotion of sustainability in the fashion industry. As a non-profit organization focused on instigating debate and disseminating scholarly research, the UCRF believes that responses from the fashion industry regarding today's climate crisis has been oversimplified or obstructed by limited business models. According to one of the founders, the UCRF hopes that the award helps bring light to the issues that continually plague the fashion industry. [24]

Purpose

The fashion industry has a clear opportunity to act differently, pursuing profit and growth while also creating new value and deeper wealth for society and therefore for the world economy. It comes with an urgent need to place environmental, social, and ethical improvements on management's agenda.[25][26] The goal of sustainable fashion is to create flourishing ecosystems and communities through its activity.[21] This may include: increasing the value of local production and products; prolonging the lifecycle of materials; increasing the value of timeless garments; reducing the amount of waste; and to reducing the harm to the environment created as a result of production and consumption. Another of its aims can sometimes be seen to educate people to practice environmentally friendly consumption by promoting the "green consumer".[27][28]

There is however a growing concern that "green consumerism" that takes profit and economic growth as primary objectives can deliver the sustainable agenda needed to mitigate and reverse the pollution, labor exploitation and inequalities fashion industry promotes and profits from. If the business model is based on selling more units of clothing, this is unsustainable, however much the garments are "eco friendly." Thus the industry has to change its basic premise for profit, yet this is slow coming as it requires a large shift in business practices, models and tools for assessment.[29] This became apparent in the discussions following the Burberry report of the brand burning unsold goods worth around £28.6m (about $37.8 million) in 2018,[30] exposing not only overproduction and subsequent destruction of unsold stock as a normal business practice, but the behaviours amongst brands that actively undermine a sustainable fashion agenda.[31]

The challenge for making fashion more sustainable requires to rethink the whole system, and this call for action is in itself not new. The Union of Concerned Researchers in Fashion has argued that the industry is still discussing the same ideas as were originally mooted in the late 1980s and early 1990s. When taking the long view and examining fashion and sustainability progress since the 1990s, there are few actual advances in ecological terms. As the Union observes, "So far, the mission of sustainable fashion has been an utter failure and all small and incremental changes have been drowned by an explosive economy of extraction, consumption, waste and continuous labour abuse." [32]

A frequently asked question of those working in the area of sustainable fashion is whether the field itself is an oxymoron.[33] This reflects the seemingly irreconcilable possibility of bringing together fashion (understood as constant change, and tied to business models based on continuous replacement of goods) and sustainability (understood as continuity and resourcefulness).[1] The apparent paradox dissolves if fashion is seen more broadly, not only as a process aligned to expansionist business models,[34][35] and consumption of new clothing, but instead as mechanism that leads to more engaged ways of living[36][22] on a precious and changing earth.[37][38]

Temporal concerns related to fashion

Fashion is, per definition, a phenomenon related to time: a popular expression in a certain time and context. This also affects the perception of what is and should be made more sustainable - if fashion should be "fast" or "slow" - or if it should be more exclusive or inclusive.[39][40] Like much other design, the objects of fashion exist in the interzone between desire and discard along a temporal axis, between the shimmering urge towards life and the thermodynamic fate of death. As noted by cultural theorist Brian Thill, "waste is every object, plus time."[41]

When it comes down to the garments themselves, their durability depends on their use and "metabolism" - certain garments are made to withstand long use (ex. outdoor and hiking wear, winter jackets) whereas other garments have a quicker turn-around (ex. a party top). This means some garments have properties and a use-life that could be made more durable, whereas others should be compostable or recyclable for quicker disintegration.[42] Some garments age well and acquire patina and a romantic enchantment not unlike the wonder, fascination and grandeur of historical ruins, whereas the derelict and discarded rags of last season is an eyesore and nuisance; the first connotes a majesty of taste, whereas the second is the underclass of waste.

"Fast fashion"

_01.jpg)

One of the most apparent reasons for the current unsustainable condition of the fashion system is related to the temporal aspects of fashion; the continuous stream of new goods onto the market, or what is popularly called "fast fashion." The term has come to signify cheap, accessible and on-trend clothes, sourced through global production chains and sold through chains such as H&M, Zara, Forever21, etc. The 2012 book Overdressed: The Shockingly High Cost of Cheap Fashion by journalist Elizabeth L. Cline gives a clear introduction to the rise of disposable consumption of fashion and its impacts on the planet, the economy and consumer relationships with clothing.[43]

However, the "fast" aspect of consumption is primarily a problem to the environment when done on a massive scale. As long as fast conspicuous consumption was reserved to the rich, the global impact was not reaching public attention or seen as a problem. That is, "fast" shopping sprees of haute couture is not seen as a problem, rather it is celebrated (for example in movies such as Pretty Woman), whereas when people with less means shop fast fashion it is seen as unethical and a problem.[44] Today, the speed of fast fashion is common across the whole industry as exclusive fashion replicates the fast fashion chains with continuous releases of collections and product drops: the quality of a garment does not necessarily translate to a slower pace of consumption and waste.

"Slow fashion"

Slow fashion can be seen as an alternative approach against fast fashion, based on principles of the slow food movement.[45][46] Characteristics of sustainable fashion match the philosophies of "slow fashion" in that emotional, ecological and ethical qualities are favored over uniform and bland convenience with minimal friction. It requires a changed infrastructure and a reduced through-put of goods. Categorically, slow fashion is neither business-as-usual nor just involving design classics. Nor is it production-as-usual but with long lead times. Slow fashion is a vision of the fashion sector built from a different starting point.[47] Slow fashion is a fashion concept that reflects a perspective, which respects human living conditions, biological, cultural diversity and scarce global resources and creates unique, personalized products.

Slow fashion challenges growth fashion's obsession with mass-production and globalized style and becomes a guardian of diversity. It changes the power relations between fashion creators and consumers and forges new relationships and trust that are only possible at smaller scales. It fosters a heightened state of awareness of the design process and its impacts on resource flows, workers, communities, and ecosystems. [48]

Slow fashion often consists of durable products, traditional production techniques or design concepts that strive to be season-less or last aesthetically and materially for longer periods of time. The impact of slowness aims to affect many points of the production chain. For workers in the textile industry in developing countries, slow fashion means higher wages. For end-users, slow fashion means that the goods are designed and manufactured with greater care and high-quality products. From an environmental point of view, it means that there is less clothing and industrial waste that are removed from use following transient trends.[49] Emphasis is put on durability; emotionally, materially, aesthetically and/or through services that prolong the use-life of garments. New ideas and product innovations are constantly redefining slow fashion, so using a static, single definition would ignore the evolving nature of the concept.

Examples of stability of expression over long times are abundant in the history of dress, not least in ethnic or folk dress, ritual or coronation robes, clerical dress, or the uniforms of the Vatican Guard.[50] The emphasis on slowness in branding is thus an approach that is specific for a niche in the market (such as Western-educated middle-class) that has since the 1990s become dominated by "fast" models. One of the earliest brands that gained global fame with an explicit focus on slow fashion, the UK brand People Tree, embraces the concept of ethical trade, manufactures all products in accordance with ethical commerce standards and supports local producers and craftsmen in developing countries. The People Tree brand is known as the first brand in the world that received the Ethical Trade Brand award, which was given in 2013. In addition to adopting ethical trade, the brand also prefers to use nature-friendly materials, textile products with GOTS certification and local, natural, recyclable material.

The concept of slow fashion is however not without its controversies, as the imperative of slowness is a mandate emerging from a position of privilege. To stop consuming "fast fashion" strikes against low income consumers whose only means to access trends is through cheap and accessible goods. Those who are already having a high position in society can afford to slow down and cement their status and position, while those on their way up resent being told to stay at the lower rungs of the status hierarchy. Another obstacle that the "slow fashion" paradigm is facing is related to consumers' behaviour towards the consumption of fashion and specifically clothing . In fact, sustainability conscious consumers, that usually take into account social and environmental implications of their purchases, may experience an attitude-behaviour gap preventing them to change their consumptions habits when it comes to choose ethical clothing. Purchasing fashion is still perceived as an action connected to social status and it is still strongly emotionally driven.

Garment use and lifespan

The environmental impact of fashion also depends on how much and how long a garment is used. With the fast fashion trend, garments tend to be used half as much as compared to 15 years ago. This is due to the inferior quality of fabrics used but also a result of a significant increase of collections that are being released by the fashion industry. Typically, a garment used daily over years has less impact than a garment used once to then be quickly discarded. Studies have shown that the washing and drying process for pair of classic jeans is responsible for almost two-thirds of the energy consumed through the whole of the jeans' life, and for underwear about 80% of total energy use comes from laundry processes.[1] Thus, use and wear practices affect the lifecycles of garments and needs to be addressed for larger systemic impact.[51]

However, there is a significant difference between making a product last from making a long-lasting product. The quality of the product must reflect the appropriate fit into its lifecycle. Certain garments of quality can be repaired and cultivated with emotional durability. Low-quality products that deteriorate rapidly are not as suitable to be "enchanted" with emotional bonds between user and product.[52]

As highlighted in the research of Irene Maldini, slowing down (in the sense of keeping garments longer) does not necessarily translate into lower volumes of purchased units.[53] Maldini's studies expose how slow fashion, in the sense of longer lasting use phase of garments, tends to indicate that garments stay in the wardrobe longer, stored or hoarded, but does not mean less resources are used in producing garments. Thus slowness comes to mean wardrobes with more lasting products, but the consumption volume and in-flow into the wardrobe/storage stays the same.[54]

Environmental concerns related to fashion

The textiles and fashion industries are amongst the leading industries that affect the environment negatively. One of the industries that greatly jeopardizes environmental sustainability is the textiles and fashion industry, which thus also bears great responsibilities. Globalization has made it possible to produce clothing at increasingly lower prices, prices so low, and collections shifting so fast, that many consumers consider fashion to be disposable.[15] However, fast, and thus disposable, fashion adds to pollution and generates environmental hazards, in production, use and disposal.

Putting the environmental perspective at the center, rather than the logic of the industry, is thus an urgent concern if fashion is to become more sustainable. The Earth Logic fashion research action plan argues for "putting the health and survival of our planet earth and consequently the future security and health of all species including humans, before industry, business and economic growth."[55] In making this argument the Earth Logic plan explicitly connects the global fashion system with the 2018 IPCC Special Report on Global Warming of 1.5 °C.

Furthermore, the Earth Logic fashion research action plan sets out a range of possible areas for work in sustainable fashion that scientific and research evidence suggests are the most likely to deliver change of the scale and pace needed to respond to challenges like climate change. Earth Logic’s point of departure is that the planet, and its people, must be put first, before profit. It replaces the logic of economic growth, which is arguably the single largest factor limiting change towards sustainable fashion, with the logic that puts earth at its center.[56]

Environmental hazards

The clothing industry has one of the highest impacts on the planet. High water usage, pollution from chemical treatments used in dyeing and preparation and the disposal of large amounts of unsold clothing through incineration or landfill deposits are hazardous to the environment.[57] There is a growing water scarcity, the current usage level of fashion materials (79 billion cubic meters annually) is very concerning, because textile production mostly takes place in areas of fresh water stress.[58] Only around 20% of clothing is recycled or reused, huge amounts of fashion product end up as waste in landfills or is incinerated.[59] It has been estimated that in the UK alone around 350,000 tons of clothing ends up as landfill every year. According to Earth Pledge, a non-profit organisation committed to promoting and supporting sustainable development, "At least 8,000 chemicals are used to turn raw materials into textiles and 25% of the world's pesticides are used to grow non-organic cotton. This causes irreversible damage to people and the environment, and still two thirds of a garment's carbon footprint will occur after it is purchased."[60] The average American throws away nearly 70 pounds of clothing per year.[61] There is an increasing concern as microfibers from synthetic fabrics are polluting the earths waters through the process of laundering. Microfibers are tiny threads that are shed from fabric. These microfibers are too small to be captured in waste water treatment plants filtration systems and they end up entering our natural water systems and as a result contaminating our food chain. One study found that 34.8% of microplastics found in oceans come from the textile and clothing industry and majority of them were made of polyester, polyethylene, acrylic, and elastane.[62] but a study off the coast of the UK and US by the Plymouth Marine Laboratory in May 2020 suggested there are at least double the number of particles as previously though.[63] Eliminating synthetic materials used in clothing products can prevent harmful synthetics and microfibers from ending up in the natural environment.

Social concerns related to fashion

One of the main social issues related to fashion concerns labor. Since the Triangle shirtwaist factory fire in 1911, labor rights in the fashion industry has been at the center of this issue.[64] The 2013 Savar building collapse at Rana Plaza, where 1138 people died, put the spotlight once again on the lack of transparency, poor working conditions and hazards in fashion production.[65][66] Attention is increasingly being placed on labour rights violations in other parts of the whole fashion product lifecycle from textile production and processing,[67][68] retail and distribution[69] and modelling[70] to the recycling of textiles.[71] Whilst the majority of fashion and textiles are produced in Asia, Central America, Turkey, North Africa, the Caribbean and Mexico, there is still production across Europe where exploitative working conditions are also found such as in Leicester in the UK Midlands[72] and Central and Eastern Europe.[73]

The fashion industry benefits from racial, class and gender inequalities.[74] These inequalities and pressure from brands and retailers in the form of low prices and short lead times contribute to exploitative working conditions and low wages.[75] Also "local" production, such as garments labeled as "Made in Italy" are engaged in global sourcing of labor and worker exploitation, bypassing unions and social welfare contracts.[76]

The number of workers employed in textiles, clothing and footwear is unknown due to the differences in statistical measures.[77] It is generally accepted that at least 25 million people, the majority women, work in garment manufacture and up to 300 million in cotton alone.[78] Nevertheless, it is really difficult to estimate exactly how many people work in the production sector, because small-scale manufacturing and contracting firms that operate illegally continue to exist within the industry. On the 24th of April 2013, Rana Plaza disaster happened as one of the biggest tragedies in history of the fashion industry. The search for the dead ended on 13 May 2013 with a death toll of 1,134. Approximately 2,500 injured people were rescued from the building alive. It is considered the deadliest garment-factory disaster in history, as well as the deadliest structural failure in modern human history.[79]

The environmental impact of fashion also affects communities located close to production sites. There is little easily accessible information about these impacts, but it is known that water and land pollution from toxic chemicals used to produce and dye fabrics and have serious negative consequences for the people living near factories.[80] At the global level, fashion is contributing to climate change and threatens biodiversity, which have social consequences for everyone.

Transparency

Supply chain transparency has been a recurring controversy for the fashion industry, not least since the Rana Plaza accident. The issue has been pushed by many labor organizations, not least Clean Clothes Campaign and Fashion Revolution. Over the last years, over 150 major brands including Everlane, Filippa K and H&M have answered by publicizing information about their factories online. Every year, Fashion Revolution publishes a Fashion Transparency Index [81][82] which rates the world's largest brands and retailers according to how much information they disclose about their suppliers, supply chain policies and practices, and social and environmental impact.

However, the focus on transparency and traceability has so far not shown the promise expected. Even if a consumer can find information on the clothing label, such as the address of the factory and how many people work there, it says nothing about the salaries and living conditions of the workers, the factory's subcontracting practices, or the environmental impact of sourcing and production. The focus on transparency has so far not bridged information with systemic action and impact. While the agenda of transparency is honourable and important, it is toothless if not paired with real improvements, policy change and legal action which holds corporations and factories responsible for misconduct.

Diversity and inclusion

In addition, fashion companies are criticised for the lack of size, age, physical ability, gender and racial diversity of models used in photo shoots and catwalks.[83] A more radical and systemic critique of social inequality in fashion concerns the exclusion and aesthetic supremacy inherent and accentuated through fashion that still remains unquestioned under the current environmentally focused discourse on sustainable fashion.[84][40]

It is worth noticing that while social "inclusivity" has become almost a norm amongst brands marketing ethical and sustainable fashion, the norm for what is considered a "beautiful" and "healthy" body keeps narrowing down under what researchers have called the current "wellness syndrome."[85] With the positive thinking of inclusivity, the assumption is that you can be whatever you want to be, and thus if you are not living up to the ideals it is your own fault. This optimism hides the diktat of aesthetic wellness, which turns inclusion into an obligation to look good and be dressed in fashionable clothes, a "democratic" demand for aesthetic as well as ethical perfection, as argued by philosopher Heather Widdows.[86]

Global concerns related to fashion

The impact of fashion across the planet is unevenly distributed. Whereas much of the benefits of cheap and accessible clothes targets and benefits the socially mobile classes in metropolitan areas in the Global North, developing countries take a much proportion of the negative impact from the fashion system in terms of waste, pollution, and ecological injustices.

The current focus on solutions related to "reduce, reuse, recycle," which are primarily promoted through brand initiatives, fails to address the global impact of the fashion system. Not only does it push responsibility for systemic issues onto the individual, but it also primarily positions fashion in a Western consumerism context, and puts Euro-centric models of status, individualism, and consumerism as universal models for social life and aspirations.

China

China has emerged as the largest exporter of fast fashion, accounting for 30% of world apparel exports.[87] However, some Chinese workers make as little as 12–18 cents per hour working in poor conditions.[88] Each year Americans purchase approximately 1 billion garments made in China. Today's biggest factories and mass scale of apparel production emerged from two developments in history. The first involved the opening up of China and Vietnam in the 1980s to private and foreign capital and investments in the creation of export-oriented manufacturing of garments, footwear, and plastics, part of a national effort to boost living standards, embrace modernity, and capitalism.[89] Second, the retail revolution within the U.S. (example Wal-Mart, Target, Nike) and Western Europe, where companies no longer manufactured but rather contracted out their production and transformed instead into key players in design, marketing, and logistics, introducing many new different product lines manufactured in foreign-owned factories in China.[89] It is the convergence of these two phenomena that has led to the largest factories in history from apparels to electronics. In contemporary global supply chains it is retailers and branders who have had the most power in establishing arrangements and terms of production, not factory owners.[90] Fierce global competition in the garment industry translates into poor working conditions for many laborers in developing nations. Developing countries aim to become a part of the world's apparel market despite poor working conditions and low pay. Countries such as Honduras and Bangladesh export large amounts of clothing into the United States every year.[88]

Economic concerns related to fashion

At the heart of the controversy concerning "fast fashion" lies the acknowledgement that the "problem" of unsustainable fashion is that cheap, accessible and on-trend clothes have become available to people of poorer means. This means more people across the world have adopted the consumption habits that in the mid-twentieth century were still reserved for the rich. To put it differently, the economic concern of fashion is that poor people now have access to updating their wardrobes as often as the rich. That is, "fast" fashion is only a problem when poor people engage in it. In alignment with this, blame is often put on poor consumers; they don't buy quality goods, buy too much and too cheap, etc.

The economic concerns of fashion also means many of the sustainable "solutions" to fashion, such as buying high-quality goods to last longer, are not accessible to people with less means. From an economic perspective, sustainability thus remains a moralizing issue of educated classes teaching the less educated "responsible consumption," and a debate that mainly concerns promoting frugality and austerity to those with less means. It is seen as an opportunity by businesses that allow resale of luxury goods. [91]

The distribution of value within the fashion industry is another economic concern, with garment workers and textile farmers and workers receiving low wages and prices.[92][93]

Sustainable clothing

Sustainable clothing refers to fabrics derived from eco-friendly resources, such as sustainably grown fiber crops or recycled materials. It also refers to how these fabrics are made. Historically, being environmentally conscious towards clothing meant (1) buying clothes from thrift stores or any shops that sell second-hand clothing, or (2) donating used clothes to shops previously mentioned, for reuse or resale. In modern times, with a prominent trend towards sustainability and being ‘green’, sustainable clothing has expanded towards (1) reducing the amount of clothing discarded to landfills, and (2) decreasing the environmental impact of agro-chemicals in producing conventional fiber crops (e.g. cotton).

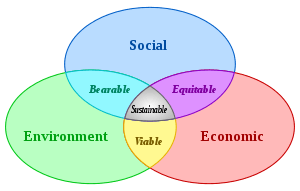

Under the accordance of sustainability, recycled clothing upholds the principle of the "Three R’s of the Environment": Reduce, Reuse, and Recycle, as well as the "Three Legs of Sustainability": Economics, Ecology, and Social Equity.

Through the utilization of recycled material for the manufacturing of clothing, this provides an additional realm of economic world profit. Sustainable Clothing will provide a new market for additional job opportunities, continuous net flow of money in the global economy, and the consumption reduction of raw materials and virgin resources. Source reduction or reducing the use of raw materials and virgin resources can ultimately reduce carbon emissions during the manufacturing process as well as the resources and carbon emissions that are related to the transportation process. This also prevents the unsustainable usage of extracting materials from the Earth by making use of what has already been used (i.e. recycling).

Recycled clothing

Recycled or reclaimed fibres are recovered from either pre or post-consumer sources. Those falling into the category of 'pre-consumer' are unworn/unused textile wastes from all the various stages of manufacture. Post-consumer textile waste could be any product which has been worn/used and have (typically) been discarded or donated to charities. Once sorted for quality and colour, they can be shredded (pulled, UK or picked, US) into a fibrous state. According to the specification and end use, these fibres can be blended together or with 'new' fibre.

While most textiles can be recycled, in the main they are downgraded almost immediately into low-quality end-uses, such as filling materials. The limited range of recycled materials available reflects the market dominance of cheap virgin fibres and the lack of technological innovation in the recycling industry. For 200 years recycling technology has stayed the same; fibres are extracted from used fabric by mechanically tearing the fabric apart using carding machines. The process breaks the fibres, producing much shorter lengths that tend to result in a low quality yarn. Textiles made from synthetic fibres can also be recycled chemically in a process that involves breaking down the fibre at the molecular level and then repolymerizing the feedstock. While chemical recycling is more energy intensive than mechanical pulling, the resulting fibre tends to be of more predictable quality. The most commonly available recycled synthetic fibre is polyester made from plastic bottles, although recycled nylon is also available[94]

In addition to promoting a sounder environment by producing newer clothing made with sustainable, innovative materials, clothing can also be donated to charities, sold into consignment shops, or recycled into other materials. These methods reduce the amount of landfill space occupied by discarded clothes. According to the United States Environmental Protection Agency's 2008 Report on Municipal Solid Waste (MSW), Generation, Recycling, and Disposal in the United States defines clothing as non-durable – generally lasts less than three years – textiles. In 2008, approximately 8.78 millions of tons of textiles were generated, 1.45 millions of tons were recovered and saved from landfills resulting in a rate of almost 17%. The EPA report also states that the amount of MSW being "Discarded" is 54%, "Recovered" is 33%, and "Combusted with Energy recovery" is 13%.[95] Approximately two-thirds of clothing materials are sent to landfills, making it the fastest growing component of waste in the household waste stream. As of 2009, textiles disposed of in landfill sites have risen from 7% to 30% within the last five years.[96]

Total MSW Generation by category, 2008, 250 million tons (before recycling)

Total MSW Generation by category, 2008, 250 million tons (before recycling)

Upcycling

Upcycling in fashion signifies the process of reusing the unwanted and discarded materials (ex. fabric scraps or clothes) into new materials or products without compromising the value and the quality of the used material. In order to implement the upcycling method, it is important to have an overview of the textile waste available because this is what dictates the garment that can be created. Using upcycling in fashion design emphasizes the importance of a local approach. Thus, both the input material (waste) and the production ideally should be local. Since levels of waste production and volumes of waste can differ by region, the first step to collecting materials for upcycling is to carry out a local textile waste study. The definition of textile waste can be production waste, pre-consumer waste, and post-consumer waste.[97]

Typically, upcycling creates something new and better from the old or used or disposed items. The process of upcycling requires a blend of factors like environmental awareness, creativity, innovation and hard work and results in a unique sustainable product. Upcycling aims at the development of products truly sustainable, affordable, innovative and creative. For example, downcycling produces cleaning rags from worn T-shirts, whereas upcycling recreates the shirts into a value-added product like unique handmade braided rug.[98]

Upcycling can be seen as one of the waste management strategies. There are different types of strategies. From least to most resource-intensive, the strategies are the reuse of product, repairing and reconditioning to keep products as long as possible, recycling the raw materials.[99] The reuse of textile products 'as is' brings significant environmental savings. In the case of clothing, the energy used to collect, sort and resell second-hand garments in between 10 and 20 times less than that needed to make a new item.[100]

Sustainable consumption practices for enhanced product life

There are negative social and environmental impacts at all stages of the fashion product life: materials production and processing, manufacture of garments, retail and marketing, use and maintenance and at the discard phase. For some products, the environmental impact can be greater at the use phase than material production.[101]

Consumer engagement

Consumer engagement challenges the "passive" mode of ready-to-wear fashion where consumers have few interfaces and little incentive to be active with their garments; to repair, change, update, swap, and learn from their wardrobe.[22] The term "folk fashion" has been used in the emphasis on craft engagements with garments where the community heritage of skills are in focus.[102] There are currently many designers trying to find ways that experiment with new models of action that deposes passivity and indifference while preserving the positive social dynamics and sensibilities fashion offers, often in relation to Alvin Toffler's notion of the "prosumer" (portmanteau of producer and consumer). Notions of participatory design, open sourcefashion, and fashion hacktivism are parts of such endeavors, mixing techniques of dissemination with empowerment, reenechantment and Paulo Freire's "Pedagogy of the Oppressed."[1][103][104][105] An example of such consumer engagement can be Giana Gonzalez and her project "Hacking Couture" which has tested such methods across the world since 2006.[106] As highlighted in the research of Jennifer Ballie, there is also an increasing interest across industry to produce unique experiences amongst users, connecting co-design with social media apps and tools to enhance the user experience of consumers.[107]

Enhancing the lifespan of products have been yet another approach to sustainability, yet still only in its infancy. Upmarket brands have long supported the lifespan of their products through product-service systems, such as re-waxing of classic outdoor jackets, or repairs of expensive hand-bags, yet more accessible brands do still not offer even spare buttons in their garments. One such approach concerns emotionally durable design, yet with fashion's dependency on continuous updates, and consumer's desire to follow trends, there is a significant challenge to make garments last long through emotional attachment. As with memories, not all are pleasant, and thus a focus on emotional attachment can result in favoring a normative approach to what is considered a good enough memory to manifest emotionally in a garment. Cultural theorist Peter Stallybrass approaches this challenge in his essay on poverty, textile memory, and the coat of Karl Marx.[108]

Clothing swapping

Clothing swapping can further promote the reduction, reuse, and recycling of clothing. By reusing clothing that's already been made and recycling clothing from one owner to another, source reduction can be achieved. This moves away from usage of new raw materials to make more clothing available for consumption. Through the method of clothing swapping, an alternative resource for consumers to ultimately save in regards to money and time is provided. It reduces transportation emissions, costs, and the time it takes to drive and search through the chaos of most clothing stores. Swapping clothes further promotes the use of sustainable online shopping and the internet as well as an increase of social bonds through online communication or effective personal communication in "clothing swap parties". The EPA states, that by reusing items, at the source waste can be diverted from ending up in landfills because it delays or avoids that item's entry in the waste collection and disposal system.[109]

Sustainable clothing through charities

People can opt to donate clothing to charities. In the UK, a charity is a non-profit organization that is given special tax form and distinct legal status.[110] A charity is "a foundation created to promote the public good".[111] People donating clothing to charitable organizations in America are often eligible for tax deductions, albeit the donations are itemized.[112]

Clothing donations

Generally, charitable organizations often sell donated clothing rather than directly giving the clothing away. Charities keep 10% of donated clothing for their high quality and retail value for the thrift shops.[113] Charities sell the rest of the donations to textile recycling businesses.[113]

Examples of charitable organization

The following is a list of few charitable organizations known for accepting clothing donations.

- Salvation Army

An Evangelical Christian-based non-profit organization founded in 1865, United Kingdom.[114]

- Goodwill Industries

A non-profit organization founded in 1902, United States, at Boston, MA. Originally started as an urban outreach [115]

- United Way

A non-profit organization originally named Charity Organization Society, established 1887, United States. Currently a coalition of charitable organizations.[116]

- Oxfam International

A non-profit organization founded in 1942, United Kingdom. Formerly Oxfam Committee for Famine Relief. Originally established to mitigate famines in Greece caused by Allied naval blockades during World War II.[117]

Controversy

There are "charities" that are actually for-profit organizations. These organizations are often multibillion-dollar firms that keep profits accrued from selling donated clothing.[118] Monetary donations are given for public goodwill, but only at relatively few percentages.[118] For example, Planet Aid, a supposedly non-profit organization that collects donated clothing, reportedly gives only 11% of its total income to charities.[118] Such organizations often use drop-off boxes to collect clothes. These drop-off boxes look similar to their non-profit counterparts, which mislead the public into donating their clothes to them.[119] Such public deception prompted backlash, one example where a mayor called for the city's removal of for-profit clothing donation bins.[120] To search for reputable charities, see Charity Navigator's website.[121]

Consignment

In layman’s terms, a clothing consignment shop sells clothes that are owned not by the shop’s owner but by the individual who had given (or consigned) the items to the shop for the owner to sell.[122] The shop owner/seller is the consignee and the owner of the items is the consignor. Both the consignor and the consignee receive portions of the profit made from the item. However, the consignor will not be paid until the items are sold. Therefore, unlike donating clothing to charities, people who consign their clothes to shops can make profit.

Textile recycling

According to an ABC News report, charities keep approximately 10% of all the donated clothing received.[113] These clothes tend to be good quality, fashionable, and high valued fabrics that can easily be sold in charities’ thrift shops. Charities sell the other 90% of the clothing donations to textile recycling firms.[113]

Textile recycling firms process about 70% of the donated clothing into industrial items such as rags or cleaning cloths.[113] However, 20-25% of the second-hand clothing is sold into an international market.[113] Where possible, used jeans collected from America, for example, are sold to low-income customers in Africa for modest prices, yet most end up in landfill as the average US sized customer is several sizes bigger than the global average.[123]

Sustainable fashion organisations and companies

There is a broad range of organisations purporting to support sustainable fashion, some representing particular stakeholders, some addressing particular issues, and some seeking to increase the visibility of the sustainable fashion movement. They also range from the local to global. It is important to examine the interests and priorities of the organisations.

Organisations

- Fashion Revolution is a not-for-profit global movement founded by Carry Somers and Orsola de Castro which highlights working conditions and the people behind the garments. With teams in over 100 countries around the world, Fashion Revolution campaigns for systemic reform of the fashion industry with a focus on the need for greater transparency in the fashion supply chain. Fashion Revolution has designated the anniversary of the Rana Plaza disaster in Bangladesh as Fashion Revolution Day. Fashion Revolution Week takes place annually during the week on which the anniversary falls. Over 1000 events take place around the world, with millions of people engaging online and offline.[124] Fashion Revolution publishes the Fashion Transparency Index annually, ranking the largest fashion brands in the world on how much they disclose about their policies, practices, procedures and social and environmental impact.[125]

- The National Association of Sustainable Fashion Designers is an organisation aimed to assist entrepreneurs with growing fashion businesses that create social change and respect the environment. They provide specialized education, training and programs that can transform the fashion industry by cultivating collaboration, sustainability and economic growth.

- Red Carpet Green Dress, founded by Suzy Amis Cameron, is a global initiative showcasing sustainable fashion on the red carpet at the Oscars.[126] Talent supporting the project includes Naomie Harris, Missi Pyle, Kellan Lutz and Olga Kurylenko.

- Undress Brisbane is an Australian fashion show that sheds light on sustainable designers in Australia.[127]

- Global Action Through Fashion is an Oakland, California-based Ethical Fashion organization working to advocate for sustainable fashion.[128]

- Ecoluxe London, a not-for-profit platform, supports luxury with ethos through hosting a biannual exhibition during London Fashion Week and showcasing eco-sustainable and ethical designers.[129][130]

- Fashion Takes Action formed in 2007 and received a non-profit status in 2011. It is an organisation that promotes social justice, fair trade and sustainable clothing production as well as advances sustainability in the fashion system through education, awareness and collaboration. FTA promotes sustainable fashion via social media, PR, hosting fashion shows, public talks, school lectures and conferences.[131]

- The Ethical Fashion Initiative, a flagship program of the International Trade Centre, a joint agency of the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) and World Trade Organization, enables artisans living in urban and rural poverty to connect with the global fashion chain.[132][133] The Initiative also works with the rising generation of fashion talent from Africa, encouraging the forging sustainable and fulfilling creative collaborations with artisans on the continent.[134][135] The Ethical Fashion Initiative is headed by Simone Cipriani.

Companies

- Eluxe Magazine, the world's first sustainable luxury magazine, was founded in 2013. The organisation also launched the Eluxe Awards, the world's first awards for sustainable luxury, in 2016.

- Eco Age, a consultancy company specialising in enabling businesses to achieve growth and add value through sustainability, is an organisation that promotes sustainable fashion. Its creative director, Livia Firth, is also the founder of the Green Carpet Challenge which aims to promote ethically made outfits from fashion designers.[136]

- Trans-America Trading Company is one of the biggest of about 3,000 textile recycler's in the United States.[137] Trans-America has processed more than 12 million pounds of post consumer textiles per year since 1942. At its 80,000-square-foot sorting facility, workers separate used clothing into 300 different categories by type of item, size, and fiber content. About 30% of the textiles are turned into absorbent wiping rags for industrial uses, and another 25–30% are recycled into fiber for use as stuffing for upholstery, insulation, and the manufacture of paper products.[138]

- ViaJoes - Sustainable clothing manufacturer producing eco friendly fabrics from recycled cotton and other sustainable products confirmed to GOTS[139] - Global Organic Textile Standard International Working Group standard

Materials

There are many factors when considering the sustainability of a material. The renewability and source of a fiber, the process of how a raw fiber is turned into a textile, the impact of preparation and dyeing of the fibers, energy use in production and preparation, the working conditions of the people producing the materials, and the material's total carbon footprint, transportation between production plants, chemicals used to keep shipments fresh in containers, shipping to retail and consumer, how the material will be cared for and washed, the processes of repairs and updates, and what happens to it at the end of life. The indexing of the textile journeys is thus extremely complex. In sustainability, there is no such thing as a single-frame approach. Issues dealt with in single frames will almost by definition lead to unwanted and unforeseen effects elsewhere. [99]

Overall, diversity in the overall fiber mix is needed; in 2013 cotton and polyester accounted for almost 85% of all fibers, and thus their impacts were, and continue to be, disproportionately magnified.[140] Also, many fibers in the finished garments are mixed to acquire desired drape, flexibility or stretch, thus affecting both care and the possibility to recycle the material in the end.

Cellulose fibers

Natural fibers are fibers which are found in nature and are not petroleum-based. Natural fibers can be categorized into two main groups, cellulose or plant fiber and protein or animal fiber. Uses of these fibers can be anything from buttons to eyewear such as sunglasses.[141]

Other than cotton, the most common plant-based fiber, cellulose fibers include: jute, flax, hemp, ramie, abaca, bamboo (used for viscose), soy, corn, banana, pineapple, beechwood (used for rayon). Alternative fibers such as bamboo (in yarn) and hemp (of a variety that produces only a tiny amount of the psychoactive component found in cannabis) are coming into greater use in so-called eco-fashions.[137]

Cotton

Cotton, also known as vegetable wool, is a major source of apparel fiber. Celebrated for its excellent absorbency, durability, and intrinsic softness, cotton accounts for over 50% of all clothing produced worldwide. This makes cotton the most widely used clothing fiber.[142] Cotton is one of the most chemical-intensive crops in the world.[143] Conventionally grown cotton uses approximately 25% of the world's insecticides and more than 10% of the world's pesticides.[144] However, growing and processing this particular fiber crop is largely unsustainable. For every pound of cotton harvested, a farmer uses up 1/3 lb of chemical, synthetic fertilizer.[145] As a whole, the US cotton production makes up 25% of all pesticides deployed in the United States. Worldwide, cotton takes up 2.4% of all arable lands yet requires 16% of the world's pesticides.[146] Furthermore, the cotton hulls contain the most potent insecticide residues. They are often used as cattle feed, which means that consumers are purchasing meat containing a concentration of pesticides.[146] The processing of cotton into usable fibers also adds to the burden on the environment. Manufacturers prefer cotton to be white so that cotton can easily be synthetically dyed to any shade of color.[147] Natural cotton is actual beige brown, and so during processing, manufacturers would add bleach and various other chemicals and heavy metal dyes to make cotton pure white.[148] Formaldehyde resins would be added in as well to form "easy care" cotton fabric.[148]

Bt cotton

To reduce the use of pesticides and other harmful chemicals, companies have produced genetically modified (GMO) cottons plants that are resistant to pest infestations. Among the GMO are cotton crops inserted with the Bt (Bacillus thuringiensis) gene.[149] Bt cotton crops do not require insecticide applications. Insects that consume cotton containing Bt will stop feeding after a few hours, and die, leaving the cotton plants unharmed.[150]

As a result of the use of Bt cotton, the cost of pesticide applications decreased between $25 and $65 per acre.[151] Bt cotton crops yield 5% more cotton on average compared to traditional cotton crops.[151] Bt crops also lower the price of cotton by 0.8 cents per pound.[151]

However, there are concerns regarding Bt technology, mainly that insects will eventually develop resistance to the Bt strain. According to an article published in Science Daily, researchers have found that members from a cotton bollworm species, Helicoverpa zea, were Bt resistant in some crop areas of Mississippi and Arkansas during 2003 and 2006.[152] Fortunately, the vast majority of other agricultural pests remain susceptible to Bt.[152]

Micha Peled's documentary exposé Bitter seeds on BT farming in India reveals the true impact of genetically modified cotton on India's farmers, with a suicide rate of over a quarter million Bt cotton farmers since 1995 due to financial stress resulting from massive crop failure and the exorbitantly high price of Monsanto's proprietary BT seed. The film also refutes false claims purported by the biotech industry that Bt cotton requires less pesticide and empty promises of higher yields, as farmers discover the bitter truth that in reality Bt cotton in fact requires a great deal more pesticide than organic cotton, and often suffer higher levels of infestation by Mealybug resulting in devastating crop losses, and extreme financial and psychological stress on cotton farmers. Due to the biotech seed monopoly in India, where Bt cotton seed has become the ubiquitous standard, and organic seed has become absolutely unobtainable, thus coercing all cotton farmers into signing Bt cotton seed purchase agreements which enforce the intellectual property interests of the biotech multinational corporation Monsanto.[153]

Organic cotton

Organic cotton is grown without the use of any genetically modification to the crops, without the use of any fertilizers, pesticides, and other synthetic agro-chemicals harmful to the land.[154] All cotton marketed as organic in the United States is required to fulfill strict federal regulations regarding how the cotton is grown.[155] This is done with a combination of innovation, science and tradition in order to encourage a good quality of life and environment for all involved. [156] Organic cotton uses 88% less water and 62% less energy than conventional cotton. [157]

Organic Cotton

Organic Cotton

Naturally colored cotton

Cotton is naturally grown in varieties of colors. Typically, cotton color can come as mauve, red, yellow, and orange hues.[147] The use of naturally colored cotton has long been historically suppressed, mainly due to the industrial revolution.[147] Back then, it was much cheaper to have uniformly white cotton as a raw source for mass-producing cloth and fabric items.[147] Currently, modern markets have revived a trend in using naturally colored cotton for its noted relevance in reducing harmful environmental impacts. One such example of markets opening to these cotton types would be Sally Fox and her Foxfiber business—naturally colored cotton that Fox has bred and marketed.[158] On an additional note, naturally colored cotton is already colored, and thus do not require synthetic dyes during process. Furthermore, the color of fabrics made from naturally colored cotton does not become worn and fade away compared to synthetically dyed cotton fabrics.[159]

Soy

Soy fabrics are derived from the hulls of soybeans—a manufacturing byproduct. Soy fabrics can be blended (i.e. 30%) or made entirely out of soy fibers.[160] Soy clothing is largely biodegradable, so it has a minimal impact on environment and landfills. Although not as durable as cotton or hemp fabrics, soy clothing has a soft, elastic feel.[161] Soy clothing is known as the vegetable cashmere for its light and silky sensation.[161] Soy fabrics are moisture absorbent, anti-bacterial, and UV resistant.[161] However, soy fabrics fell out of public knowledge during World War II, when rayon, nylon, and cotton sales rose sharply.[162]

Soybean Plant

Soybean Plant

Hemp

Hemp, like bamboo, is considered a sustainable crop. It requires little water to grow, and it is resistant to most pests and diseases.[163] The hemp plant's broad leaves shade out weeds and other plant competitors, and its deep taproot system allows it to draw moisture deep in the soil.[164] Unlike cotton, many parts of the hemp plant have a use. Hemp seeds, for example, are processed into oil or food.[163] Hemp fiber comes in two types: primary and secondary bast fibers. Hemp fibers are durable and are considered strong enough for construction uses.[164] Compared to cotton fiber, hemp fiber is approximately 8 times the tensile strength and 4 times the durability.[164]

Hemp fibers are traditionally coarse, and have been historically used for ropes rather than for clothing. However, modern technology and breeding practices have made hemp fiber more pliable, softer, and finer.

Fibers from a Hemp plant.

Fibers from a Hemp plant.

Bamboo

Bamboo fabrics are made from heavily pulped bamboo grass. Making clothing and textile from bamboo is considered sustainable due to the lack of need for pesticides and agrochemicals.[165] Naturally disease and pest resistant, bamboo is also fast growing. Compared to trees, certain varieties of bamboo can grow 1–4 inches long per day, and can even branch and expand outward because of its underground rhizomes.[166] Like cotton fibers, bamboo fibers are naturally yellowish in color and are bleached white with chemicals during processing.

Kombucha (SCOBY)

Burnished by a grant from the US. Environmental Protection Agency, associate professor Young-A Lee and her team are growing vats of gel-like film composed of cellulose fiber, a byproduct of the same symbiotic colonies of bacteria and yeast (abbreviated SCOBY) found in another of the world's popular "live culture" foods: kombucha. Once harvested and dried, the resulting material has a look and feel much like leather.[167] The fibres are 100 percent biodegradable, they also foster a cradle-to-cradle cycle of reuse and regeneration that leaves behind virtually zero waste. However, this material takes a long time to grow about three to four weeks under lab-controlled conditions. Hence mass production is an issue. In addition, tests revealed that moisture absorption from the air softens this material makes it less durable. Researchers also discovered that cold conditions make it brittle.[167]

S.Café

S.Café technology involves recycling used ground coffee beans into yarns. A piece of S.Café fabric is made with less energy in the process and is able to mask body odour. In addition, S.Café yarn offers 200% faster drying time compared to conventional cotton, with the ability to save energy in the process.[168]

S. Café coffee grounds come with numerous microscopic pores, which create a long-lasting natural and chemical free shield for yarn or fiber, reflecting UV rays and provide a comfortable outdoor experience.[168]

Other cellulose fibers

Other alternative biodegradable fibers being developed by small companies include:

Protein fibers

Protein fibers originate from animal sources and are made up of protein molecules. The basic elements in these protein molecules being carbon, hydrogen oxygen and nitrogen.[172] Natural protein fibers include: wool, silk, angora, camel, alpaca, llama, vicuna, cashmere, and mohair.

Wool

Just as in cotton production, pesticides are used in the cultivation of wool, although quantities are considerably smaller and it is thought that good practice can significantly limit any negative environmental impact. Sheep are treated either with injectable insecticides, a pour-on preparation or dipped in a pesticide bath to control parasite infection, which if left untreated can have serious welfare implications for the flock. When managed badly, these pesticides can cause harm to human health and watercourses both on the farm and in subsequent downstream processing. [99]

Silk

Most commercially produced silk is of the cultivated variety and involves feeding the worms a carefully controlled diet of mulberry leaves grown under special conditions. Selected mulberry trees are grown to act as homes for the silkworms. The fibers are extracted by steaming to kill the silk moth chrysalis and then washed in hot water to degum the silk. [99]

Other natural materials

MuSkin

Italian company Zero Grado Espace has developed MuSkin, an alternative to leather made from the cap of the phellinus ellipsoideus mushroom, a parasitic fungus that grows in subtropical forests. It is water repellent and contains natural penicillin substances which limit bacteria proliferation.[173]

Wild rubber

Wild Rubber, developed by Flavia Amadeu and Professor Floriano Pastore at the University of Brazil, is an initiative that promotes wild rubber material which comes from the sap or latex of the pará rubber tree that grows within a biodiverse ecosystem in the Amazon Rainforest, Acre, Brazil. It is tapped by local communities who typically have a close relationship the forest and will gather medicinal plants or wild food during their tapping rounds.[174]

Qmilk

Qmilch GmbH, a German company has innovated a process to produce a textile fiber from casein in milk but it cannot be used for consumption. Qmilk fiber is made from 100% renewable resources. In addition, for the production of 1 kg of fiber Qmilch GmbH needs only 5 minutes and max. 2 liters of water.[175] This implies a particular level of cost efficiency and ensures a minimum of CO2 emissions. Qmilk fiber is biodegradable and leaves no traces. In addition, it is naturally antibacterial, especially against the bacterial strains, Staphylococcus aureus and Pseudomonas aeruginosa and is ideal for people that suffer from textile allergies.

Fabrics made from Qmilk fiber provide high wearing comfort and a silky feel. The organic fiber is tested for harmful substances and dermatologically tested for the wearer's skin and body compatibility 0% chemical additives.[175]

Manufactured fibers

Manufactured fibers sit within three categories:[176] Manufactured cellulosic fibers, manufactured synthetic fibers and manufactured protein fiber (azlon). Manufactured cellulosic fibers include modal, Lyocell (also known under the brand name Tencel), rayon/viscose made from bamboo, rayon/viscose made from wood and polylactic acid (PLA). Manufactured synthetic fibers include polyester, nylon, spandex, acrylic fiber, polyethylene and polypropylene (PP). Azlon is a manufactured protein fiber.

PET plastic

PET plastics are also known as Polyethylene terephthalate(PETE). PET's recycling code, the number within the three chasing arrows, is one. These plastics are usually beverage bottles (i.e. water, soda, and fruit juice bottles). According to the EPA, plastic accounts for 12% of the total amount of waste we produce.[95] Recycling plastic reduces air, water, and ground pollution. Recycling is only the first step; investing and purchasing products manufactured from recycled materials is the next of many steps to living sustainably.

- Recyclables at transfer station, Gainesville, FL.

Clothing can be made from plastics. Seventy percent of plastic-derived fabrics come from polyester, and the type of polyester most used in fabrics is polyethylene terephthalate (PET).[177] PET plastic clothing come from reused plastics, often recycled plastic bottles.[178] The Coca-Cola Company, for example, created a "Drink2Wear" line of T-shirts made from recycled bottles.[179] Generally, PET plastic clothing are made from recycled bottles as follows: plastic bottles are collected, compressed, baled, and shipped into processing facilities where they will be chopped into flakes, and melted into small white pellets. Then, the pellets are processed again, and spun into yarn-like fiber where it can be made into clothing.[180] One main benefit of making clothes from recycled bottles is that it keep the bottles and other plastics from occupying landfill space. Another benefit is that it takes 30% less energy to make clothes from recycled plastics than from virgin polyesters.[181]

Production

Whereas many producers have since the turn of the century been striving for a cradle-to-cradle model of production, or a circular economy, there has so far been no successful example of fully sustainable production, as there is environmental impact from all extractive production practices (in processes of material production, dying, assembly, accessorizing, shipping, retail, washing, recycling etc.) There are many small initiatives towards change, yet so far all these incremental improvements have been drowned by the explosive popularity of "fast" fashion and its economy of extraction, consumption, waste.

Producers

The global political economy and legal system supports a fashion system that enables fashion that has devastating environmental, social, cultural and economic impacts to be priced at a lower price than fashion which involves efforts to minimize harm in the growth, manufacturing, and shipping of the products. This results in higher prices for fashion made from reduced impact materials than clothing produced in a socially and environmentally damaging way (sometimes referred to as conventional methods).[182]

Innovative fashion is being developed and made available to consumers at different levels of the fashion spectrum, from casual clothing to haute couture which has a reduced social and environmental impact at the materials and manufacture stages of production[137] and celebrities, models, and designers have recently drawn attention to socially conscious and environmentally friendly fashion.

3D seamless knitting

3D seamless knitting is a technology that allows an entire garment to be knit with no seams. This production method is considered a sustainable practice due to its reduction in waste and labor. By only using the necessary materials, the producers will be more efficient in their manufacturing process. This production method is similar to seamless knitting, although traditional seamless knitting requires stitching to complete the garment while 3D seamless knitting creates the entire garment, eliminating additional work. The garments are designed using 3D software unlike traditional flat patterns. Shima Seiki and Stoll are currently the two primary manufacturers of the technology. The technology is produced through the use of solar energy and they are selling to brands like Max Mara.[183]

Zero-waste

Zero-waste design is a concept that, although has been prevalent for many years, is increasingly being integrated into production. Zero-waste design is used through multiple industries but is very applicable in developing patterns for garments.[103] The concept of zero-waste pattern making is designing the pattern for a garment so that when the textile is cut, there is no extra fabric going to waste. This means the pattern pieces for a garment fit together like puzzle pieces in order to use the entire amount of fabric provided, creating no waste in this step of production.[184]

Dyeing

Traditional methods of dyeing textiles are incredibly harmful towards the earth's water supply, creating toxic chemicals that effect entire communities.[185] An alternative to traditional water dyeing is scCO2 dyeing (super critical carbon dioxide). This process creates no waste by using 100% of the dyes, reducing energy by 60% with no auxiliary chemicals, and leaving a quarter of the physical footprint of traditional dyeing. Different names for this process are Drydye and Colordry.[186] Another company called Colorep has patented Airdye, a similar process that they claim uses 95% less water and up to 86% less energy than traditional dyeing methods.[187]

Comparison websites and ecolabels

So far, no brand can label itself as fully sustainable, and controversies are abundant on exactly how to use the concept in relation to fashion, if it can be used at all, or if labels such "slow" and "sustainable" fashion are inherently an oxymoron.[39] Brands that sell themselves as sustainable often still lack systems to deal with oversupply, take back used clothes, fully recycle fibers, offer repair services, or even support the life of the garment during use (such as instructions on washing, care and repair). Almost no brands offer spare parts, which says a lot about the general life expectancy of garments in general: brand are not supporting consumers to make garments last.

That said, some comparison websites (such as Rank A Brand, Good On You, ...) exist which compare fashion brands on their sustainability record, and these can at least give an indication to consumers.[188][189][190]

There are much ecolabels in existence which focus on textile.[191] Some notable[192] ecolabels include:

- EU Ecolabel

- Fair Trade Certified

- Global Organic Textile Standard

- Oeko-Tex Standard 1000

Sustainable textile brands

Some brands that sell themselves as sustainable are listed below;

- Eastern European prisoners are designing sustainable prison fashion in Latvia and Estonia under the Heavy Eco label,[193] part of a trend called "prison couture".[194]

- Other sustainable fashion brands include Elena Garcia, Nancy Dee, By Stamo, Outsider Fashion, Beyond Skin, Oliberté, Hetty Rose, DaRousso, KSkye the Label,[195] and Eva Cassis.[129][196][197][198][199][200][201]

- The brand Boll & Branch make all of their bedding products from organic cotton and have been certified by Fair Trade USA.[202]

- The Hemp Trading Company is an ethically driven underground clothing label, specializing in environmentally friendly, politically conscious street wear made of hemp, bamboo, organic cotton and other sustainable fabrics.[203]

- Patagonia, a major retailer in casual wear, has been selling fleece clothing made from post-consumer plastic soda bottles since 1993.[137]

- Everlane, a brand that offered the customer a full breakdown of how much it would cost to make each product, from the price of the raw materials and transportation to exactly how much of a markup Everlane would take.[204]

- Pact, a brand that produced Fair Trade Factory Certified™ clothing made out of organic cotton.[205]

- People Tree is a brand that actively supports farmers, producers and artisans through 14 producer groups, in 6 countries. They are a part of the WFTO community and a representative of Fair Trade.[206]

- Wrangler, a historic denim brand, launched a sustainable denim collection called Indigood that uses foam instead of water to dye denim, resulting in 100 per cent less water used, and 60 per cent less energy used.[207]

Designers

There is no certain stable model among the designers for how to be sustainable in practice, and the understanding of sustainability is always a process or a work-in-progress, and varies by who defines what is "sustainable;" farmers or animals, producers or consumers, managers or workers, local businesses or neighborhoods.[28] Thus critical scholars would label much of the business-driven discourse on sustainability as "greenwashing" as under the current economic paradigm, "sustainability" is primarily defined as keeping the wheels of perpetual production and consumption turning; to keep the "perpetuum mobile" of fashion running and in perpetual motion.[208]

There are some designers that experiment in making fashion more sustainable, with various degrees of impact;

- Ryan Jude Novelline created a ballroom gown constructed entirely from the pages of recycled and discarded children's books known as The Golden Book Gown that "prove[d] that green fashion can provide as rich a fantasia as can be imagined."[209][210]

- Eco-couture designer Lucy Tammam uses eri silk (ahimsa/peace silk) and organic cotton to create her eco friendly couture evening and bridal wear collections.[211][212]

- Amal Kiran Jana is a designer from India and the founder of Afterlife Project which is a sustainability development project supporting global and unique designers in 360 degrees. [213]

- Stella McCartney pushes the agenda for sustainable fashion that is animal and eco-friendly. She also uses her name and her brand as a platform to push for a greener fashion industry. The brand uses the EP&L tool which was created to help companies understand their environmental impact by measuring greenhouse gas emissions, land use, water use, water pollution, air pollution and waste across the entire global supply chain.[214]

Controversies

A question at the foundation of sustainable fashion concerns exactly what is to be "sustained" of the current model of fashion. Controversies thus emerge what stakeholder agendas should be prioritized over others.

Greenwashing

A major controversy on sustainable fashion concerns how the "green" imperative is used as a cover-up for systemic labor exploitation, social exclusion and environmental degradation, what is generally labelled as greenwashing. Market-driven sustainability can only address sustainability to a certain degree as brands still need to sell more products in order to be profitable. Thus almost any initiative towards addressing ecological and social issues still contributes to the damage. In a 2017 report, the industry projects that the overall apparel consumption will rise by 63%, from 62 million tons today to 102 million tons in 2030, thus effectively erasing any environmental gains made by current initiatives.[215] As long as the business models of fashion brands are based on growth as well as production and sales of high quantities of garment, almost all initiatives from the industry remains labelled as greenwashing.

Materials controversies

Though organic cotton is considered a more sustainable choice for fabric, as it uses fewer pesticides and chemical fertilizers, it remains less than 1% global cotton production. Hurdles to growth include cost of hand labor for hand weeding, reduced yields in comparison to conventional cotton and absence of fiber commitments from brands to farmers before planting seed. The up front financial risks and costs are therefore shouldered by the farmers, many of whom struggle to compete with economies of scale of corporate farms.

Though some designers have marketed bamboo fiber, as an alternative to conventional cotton, citing that it absorbs greenhouse gases during its life cycle and grows quickly and plentifully without pesticides, the conversion of bamboo fiber to fabric is the same as rayon and is highly toxic. The FTC ruled that labeling of bamboo fiber should read "rayon from bamboo". Bamboo fabric can cause environmental harm in production due to the chemicals used to create a soft viscose from hard bamboo.[216] Impacts regarding production of new materials make recycled, reclaimed, surplus, and vintage fabric arguably the most sustainable choice, as the raw material requires no agriculture and no manufacturing to produce.[217] However, it must be noted that these are indicative of a system of production and consumption that creates excessive volumes of waste.

Second-hand controversies

Used clothing is sold in more than 100 countries. In Tanzania, used clothing is sold at the mitumba (Swahili for "secondhand") markets. Most of the clothing is imported from the United States.[137] However, there are concerns that trade in secondhand clothing in African countries decreases development of local industries even as it creates employment in these countries.[218] While the reuse of materials brings resource savings, there are some concerns that the influx of cheap, second-hand clothing, particularly in Africa, has undermined indigenous textile industries. With the result that clothing collected in the West under the guise of 'charitable donations' could actually create more poverty. [99] And the authors of Recycling of Low Grade Clothing Waste warn that in the long run, as prices and quality of new clothing continue to decline, the demand for used clothing will also diminish.[219]

Marketing controversies

The increase in western consumers’ environmental interest is motivating companies to use sustainable and environmental arguments solely to increase sales. Because environmental and sustainability issues are complex, it is also easy to mislead consumers. Companies can use sustainability as a “marketing ploy” something that can be seen as greenwashing.[220] Greenwashing is the deceptive use of an eco-agenda in marketing strategies.[28] It refers mostly to corporations that make efforts to clean up their reputation because of social pressure or for the purpose of financial gain.

Future of fashion sustainability