Sudbury Basin

The Sudbury Basin /ˈsʌdbəri/, also known as Sudbury Structure or the Sudbury Nickel Irruptive, is a major geological structure in Ontario, Canada. It is the third-largest known impact crater or astrobleme on Earth, as well as one of the oldest.[1] The crater formed 1.849 billion years ago in the Paleoproterozoic era.[2]

| Sudbury Structure | |

NASA World Wind satellite image of the Sudbury astrobleme | |

| Impact crater/structure | |

|---|---|

| Confidence | Confirmed |

| Diameter | 130 km (81 mi) |

| Age | 1849 Ma Paleoproterozoic |

| Exposed | Yes |

| Drilled | Yes |

| Location | |

| Coordinates | 46°36′N 81°11′W |

| Country | Canada |

| Province | Ontario |

Location of the crater in Canada | |

_Ontario.jpg)

The basin is located on the Canadian Shield in the city of Greater Sudbury, Ontario. The former municipalities of Rayside-Balfour, Valley East and Capreol lie within the Sudbury Basin, which is referred to locally as "The Valley". The urban core of the former city of Sudbury lies on the southern outskirts of the basin.

The Sudbury Basin is located near a number of other geological structures, including the Temagami Magnetic Anomaly, the Lake Wanapitei impact crater, the western end of the Ottawa-Bonnechere Graben, the Grenville Front Tectonic Zone and the eastern end of the Great Lakes Tectonic Zone, although none of the structures are directly related to each other in the sense of resulting from the same geological processes.

Formation

The Sudbury basin formed as a result of an impact into the Nuna supercontinent from a bolide approximately 10–15 km (6.2–9.3 mi) in diameter that occurred 1.849 billion years ago[2] in the Paleoproterozoic era.

Debris from the impact was scattered over an area of 1,600,000 km2 (620,000 sq mi) thrown more than 800 km (500 mi); rock fragments ejected by the impact have been found as far away as Minnesota.[3]

Models suggest that for such a large impact, debris was most likely scattered globally,[4] but has since been eroded away. Its present size is believed to be a smaller portion of a 130 km (81 mi) round crater that the bolide originally created. Subsequent geological processes have deformed the crater into the current smaller oval shape. Sudbury Basin is the third-largest crater on Earth, after the 300 km (190 mi) Vredefort crater in South Africa, and the 150 km (93 mi) Chicxulub crater under Yucatán, Mexico.

Structure

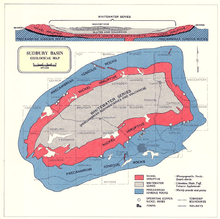

The full extent of the Sudbury Basin is 62 km (39 mi) long, 30 km (19 mi) wide and 15 km (9.3 mi) deep, although the modern ground surface is much shallower.

The main units characterizing the Sudbury Structure can be subdivided into three groups: the Sudbury Igneous Complex (SIC), the Whitewater Group, and footwall brecciated country rocks that include offset dikes and the Sub layer. The SIC is believed to be a stratified impact melt sheet composed from the base up of sub layer norite, mafic norite, felsic norite, quartz gabbro, and granophyre.

The Whitewater Group consists of a suevite and sedimentary package composed of the Onaping (fallback breccias), Onwatin, and Chelmsford Formations in stratigraphic succession. Footwall rocks, associated with the impact event, consist of Sudbury Breccia (pseudotachylite), footwall breccia, radial and concentric quartz dioritic breccia dikes (polymict impact melt breccias), and the discontinuous sub layer.

Because considerable erosion has occurred since the Sudbury event, an estimated 6 km (3.7 mi) in the North Range, it is difficult to directly constrain the actual size of the diameter of the original transient cavity, or the final rim diameter.[5]

The deformation of the Sudbury structure occurred in five main deformation events (by age in Mega years):

- formation of the Sudbury Igneous Complex (1849 Ma)[2]

- Penokean orogeny (1890–1830 Ma)

- Mazatzal orogeny (1700–1600 Ma)[6]

- Grenville orogeny (1400–1000 Ma)

- Lake Wanapitei impact (37 Ma)

Disputes over origin

Some 1.8 billion years of weathering and deformation made it difficult to prove that a meteorite was the cause of the Sudbury geological structures. A further difficulty in proving that the Sudbury complex was formed by meteorite impact rather than by ordinary igneous processes was that the region was volcanically active at around the same time as the impact, and some weathered volcanic structures can look like meteorite collision structures. Since its discovery, a layer of breccia has been found associated with the impact event[7] and stressed rock formations have been fully mapped.

Geologists reached consensus by about 1970 that the Sudbury basin was formed by a meteorite impact. Reports published in the late 1960s described geological features that were said to be distinctive of meteorite impact, including shatter cones[8] and shock-deformed quartz crystals in the underlying rock.[9] In 2014, analysis of the concentration and distribution of siderophile elements as well as the size of the area where the impact melted the rock indicated that a comet rather than an asteroid most likely caused the crater.[10][11]

Modern uses

The large impact crater filled with magma containing nickel, copper, platinum, palladium, gold, and other metals. In 1856 while surveying a baseline westward from Lake Nipissing, provincial land surveyor Albert Salter located magnetic abnormalities in the area that were strongly suggestive of mineral deposits. The area was then examined by Alexander Murray of the Geological Survey of Canada, who confirmed "the presence of an immense mass of magnetic trap".

Due to the then-remoteness of the Sudbury area, Salter's discovery did not have much immediate effect. The later construction of the Canadian Pacific Railway through the area, however, made mineral exploration more feasible. The development of a mining settlement occurred in 1883 after earth moving at the railway construction site revealed a large concentration of nickel and copper ore at what is now the Murray Mine site.

As a result of these metal deposits, the Sudbury area is one of the world's major mining communities. The region is one of the world's largest suppliers of nickel and copper ores. Most of these mineral deposits are found on the outer rim of the basin.

Due to the high mineral content of its soil, the floor of the basin is among the best agricultural land in Northern Ontario, with numerous vegetable, berry, and dairy farms located in the valley. However, because of its northern latitude, it is not as productive as agricultural lands in the southern portion of the province. Accordingly, the region primarily supplies products for consumption within Northern Ontario, and is not a major food exporter.

An Ontario Historical Plaque was erected by the province to commemorate the discovery of the Sudbury Basin.[12]

Astronaut training

NASA used the site to geologically train the Apollo astronauts in recognizing rocks formed as the result of a very large impact, such as breccias. Astronauts who would use this training on the Moon included Apollo 15's David Scott and James Irwin, Apollo 16's John Young and Charlie Duke, and Apollo 17's Gene Cernan and Jack Schmitt. Notable geologist instructors included William R. Muehlberger.[13]

See also

References

- "Sudbury". Earth Impact Database. Planetary and Space Science Centre University of New Brunswick Fredericton. Retrieved 2017-10-09.

- Davis, Donald W. (January 23, 2008). "Sub-million-year age resolution of Precambrian igneous events by thermal extraction-thermal ionization mass spectrometer Pb dating of zircon: Application to crystallization of the Sudbury impact melt sheet". Geology. 36 (5): 383–386. Bibcode:2008Geo....36..383D. doi:10.1130/G24502A.1.

- Associated Press: "Ontario crater debris found in Minn.", Star Tribune, July 15, 2007

- Melosh, J. (1989)Impact Cratering: A Geologic Process. Oxford University Press.

- Pye, E.G., Naldrett, A.J. & Giblin, P.E. (1984) The Geology and Ore Deposits of the Sudbury Structure. Ontario Geological Survey, Special Volume 1, Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources.

- Riller, U (2005). "Structural characteristics of the Sudbury impact structure, Canada: Impact-induced versus orogenic deformation-A review". Meteoritics & Planetary Science. 40 (11): 1723–1740. doi:10.1111/j.1945-5100.2005.tb00140.x.

- Beales, FW; Lozej, GP (1975). "Sudbury Basin Sediments and the Meteoritic Impact Theory of Origin for the Sudbury Structure". Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences. 12 (4): 629–635. doi:10.1139/e75-056.

- Bray, JG (1966). "Shatter Cones at Sudbury". The Journal of Geology. 74 (2): 243–245. doi:10.1086/627158.

- French, BM (1967). "Sudbury Structure, Ontario: Some Petrographic Evidence for Origin by Meteorite Impact". Science. 156 (3778): 1094–1098. doi:10.1126/science.156.3778.1094. hdl:2027/pst.000020681982.

- Petrus, JA; Ames, DE; Kamber, BS (2015). "On the track of the elusive Sudbury impact: geochemical evidence for a chondrite or comet bolide". Terra Nova. 27 (1): 9–20. doi:10.1111/ter.12125.

- Ghose, Tia (November 18, 2014). "A Comet Did It! Mystery of Giant Crater Solved". LiveScience. Retrieved November 18, 2014.

- Brown, Alan L. "Discovery of the Sudbury Nickel Deposits". Ontario's Historical Plaques. Retrieved 2018-05-12.

- Phinney, William (2015). Science Training History of the Apollo Astronauts. NASA SP -2015-626. pp. 247, 252.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sudbury_Basin. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sudbury Basin. |

- Earth Impact Database

- Fallbrook Gem and Mineral Society – Sudbury Structure page

- Morgan, JW; Walker, RJ; Horan, MF; Beary, ES; Naldrett, AJ (January 2002). "190Pt– 186Os and 187Re– 187Os systematics of the Sudbury Igneous Complex, Ontario" (PDF). Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta. 66 (2): 273–290. doi:10.1016/S0016-7037(01)00768-2.

- Aerial Exploration of the Sudbury Impact Structure