Stereobelt

The Stereobelt was the first patented personal stereo audio cassette player. It was devised by the German-Brazilian Andreas Pavel.[1]

A former television executive and book editor, Pavel devised the Stereobelt to "add a soundtrack to real life" by allowing the user to play high-fidelity music through headphones while participating in daily activities. Pavel says the initial test of a prototype hardware took place in February 1972 in St. Moritz, Switzerland, when Pavel pushed the play button to start the song Push Push by Herbie Mann and Duane Allman. Pavel experienced a "floating" sensation as he listened to the music and watched the mountain snow fall, realizing that his new device could provide "the means to multiply the aesthetic potential of any situation."[1]

Pavel approached electronics manufacturers such as ITT, Grundig, Yamaha and Philips with his invention, but said the companies felt that no one would ever want to wear headphones in public for listening to music. Frustrated with his lack of progress, and learning that it was important to protect his idea, Pavel filed a patent for the Stereobelt in Italy in 1977, followed by patent applications in Germany and the United Kingdom in 1978, and later the United States and Japan.

Legal battle

Sony began selling their Walkman personal stereo in 1979. The prototype Walkman was a playback only adaptation of the existing Sony Pressman, a compact cassette recorder and portable audio player for journalists. In negotiations that began in 1980 and ended in 1986, Sony agreed to pay Pavel limited royalties for the sales of certain Walkman models sold in his home country of Germany only (about DM 150,000, almost 1% of Sony's Walkman profit in Germany).

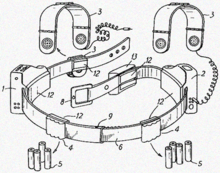

A second round of legal battles between Pavel and Sony that began in 1990 through the England and Wales Patents County Court ended in 1996 after Judges ruled in Sony's favour, leaving Pavel to pay almost 3 million euros ($3.68 million) in court costs.[2] Sony contended the Walkman evolved from a succession of portable mono and stereo cassette recorders spanning over a decade, starting with the TC-50 in 1968, illustrated in court with chronological charts.[3] They never sought to file patents on the Walkman, its legal team argued, because the technology was innovative but not wholly inventive, rendering any such filing invalid.[4][5] Counsel representing Sony and Toshiba, who also appeared in opposition, further argued that Pavel's idea consisted of multiple components, namely a belt-like garment that housed an amplifier and battery pack separately, and lacked a stability mechanism to counter movement. Pavel's legal representatives countered that, although the patent describes a stereo system in conjunction with a belt, "his claim covers all personal stereos"[6] and Sony's own charts appeared to show their personal audio equipment getting larger with time, not smaller or more refined.[3]

Pavel's legal challenge was lost in 1993 and his patent revoked. Judge Peter Ford adjudicated the patent to be invalid because the technology was "obvious and not significantly inventive". The case proceeded to the Appeals Court where Pavel lost again in 1996.[7] The Court of Appeal reexamined a range of prior art and considered testimony from new witnesses. Various brand models were the subject of dispute, including stereophonic cassette players and radios that supported headphone use; some with small carry handles, others belt clips or shoulder straps. Pavel's team argued that "a belt in the form of a shoulder strap was not for personal wear."[8] It was submitted that if their client's invention was obvious, as held by the original Judge, such a design would have been patented sooner. It was the "concept" of a personal stereo player that "changed the listening habits of the world", not the design package, which Pavel's team described as "window dressing". This was borne out by the "explosive success" of the Walkman. Lord Justice John Hobhouse, Lord Justice Brian Neill, and Lord Justice William Aldous disagreed, citing the Walkman's form factor, minimal operating power, and ability to reproduce high-quality sound at a reasonable cost as central reasons for its appeal and popularity. "Although the Walkman was a great commercial success, the attempt to rely upon that success to support invention is fallacious".[8][3]

The ruling was foreshadowed by New Scientist shortly after the British patent was granted to Pavel in 1982. Claiming a "monopoly" on personal stereo equipment, the magazine cautioned that his diagram might prove too broad and of no practical legal value. "Sony's breakthrough with Walkman was in the players high quality reproduction, low powered consumption and the tape drives ability to run smoothly, even when the wearer runs." Details for which, the magazine noted, were absent in Pavel's patent.[9]

Finally in 2003, with Pavel threatening to file infringement proceedings in the remaining two countries where he held patents, Sony approached him with a view to settling the matter amicably, which led to both parties signing a contract and confidentiality agreement in 2004. The settlement was reported to be a cash payment in the "low eight figures" and ongoing royalties of the sale of certain Walkman models.[1] After signing the agreement, Pavel told Der Spiegel he planned to approach other audio manufacturers such as Apple Inc. over their digital iPod media player.[2]

See also

References

- US patent 4412106, Andreas Pavel, "High fidelity stereophonic reproduction system", issued 1983-10-25

Footnotes

- Rohter, Larry (December 17, 2005). "Unlikely trendsetter made earphones a way of life". The New York Times.

- Dumout, Estelle (June 4, 2004). "Sony pays millions to inventor in Walkman dispute". CNET News.

- "See you in court". The Independent. Retrieved August 24, 2019.

- "Patents: Saved by the belt". New Scientist. Retrieved August 23, 2019.

- "A patent mystery: Who invented the portable personal stereo?". The Independent. Retrieved August 23, 2019.

- "Patents: Walkman's wrangle heard in court". New Scientist. Retrieved August 23, 2019.

- "Inventor fights Sony for patent". The Independent. Retrieved August 23, 2019.

- Andreas Pavel v Sony Corporation, Sony UK Ltd, Toshiba Ltd. 21 March, 1996. CCRTF 93/1605/B

- "Stationary patent (on Google Books)". New Scientist. Vol. 93 no. 1288. 14 January 1982.