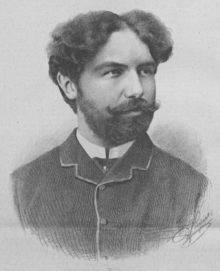

Stéphan Elmas

Stéphan Elmas (Armenian: Ստեփան Էլմաս; 1862 – August 11, 1937) was an Armenian composer, pianist and teacher.[1]

Life

Elmas was born into a family of wealthy entrepreneurs in Smyrna (now İzmir), a city in the Ottoman Empire. It was soon discovered that the little boy was a child prodigy: he began taking piano lessons and writing short piano pieces under the tutelage of a local music teacher, Mr. Moseer, and already at the age of thirteen, the young virtuoso performed an all-Liszt piano recital.

In July 1879, with the encouragement of his teacher – but against the wishes of his family – Stéphan Elmas left for Weimar, Germany, hoping to audition for Franz Liszt. Here he was able to meet the great master: Liszt advised him to go to Austria and work with Professor Anton Door[2] at the Vienna Conservatory [a.k.a. University of Music and Performing Arts, Vienna] and Franz Kremm, the distinguished composer and church musician.

In Vienna, the seventeen-year-old Stéphan divided his time between studying the piano and composition, making his Vienna debut in 1885: an event which received many accolades in the press. Elmas continued to compose, writing many character pieces, including waltzes, mazurkas, nocturnes and impromptus. He dedicated his 6 Etudes (1881) to Franz Liszt and a number of pieces to Victor Hugo.

Elmas stayed in contact with Liszt and frequently sought his advice. In 1886, he briefly returned to his native Smyrna to attend his father’s funeral, but returned to Vienna convinced that Europe had much more to offer him. On February 24, 1887, he gave a highly successful recital in Vienna’s Saal Bösendorfer. A busy concert schedule followed, with Elmas scoring artistic triumphs in France, England, Germany, Austria and Italy. He mostly programmed his own works, but also performed Beethoven, Chopin and Schumann.

During his travels, Elmas became closely acquainted with, among others, the Russian composer and pianist Anton Rubinstein, the French composer Jules Massenet, the French pianist Joseph-Édouard Risler and the French lexicographer Guy de Lusignan. In 1912, he took up permanent residence in Geneva, Switzerland, where he continued to compose, teach and perform. Over time, Elmas became increasingly hard of hearing and grew somewhat of a bitter recluse, cutting himself off from the world.

Thankfully, he befriended Aimée Rapin (1868–1956),[3] the armless Swiss painter, who nursed and consoled him during these difficult times. Elmas was also haunted by the tragic events of the 1915 Armenian Genocide by the Ottoman Turks. Fortunately, his family was able to escape to Athens following the Great Fire of Smyrna in 1922 which followed the Turkish occupation of the city.

Stéphan Elmas dictated his memoirs to Krikor-Hagop, a young journalist. His piano, along with his manuscripts and reminiscences, is now housed at the Charents Museum of Literature and Arts of Armenia. The composer died in Geneva and was buried in the city’s Plainpalais cemetery.[4]

Elmas composed rapidly and with great ease. Perhaps this explains why he sometimes did not revise his compositions sufficiently. However, many of his works are of high quality and perhaps he was most successful in composing his elegant and stylish salon pieces. These pieces seem to be composed for an earlier time: Elmas’s compositions tend to hearken back towards the style of earlier, Romantic composers, rather than forward to the challenging times that were shaping the musical world at the beginning of the new century.

Established in 1988 under the artistic guidance of Alexandre Siranossian, the Stéphan Elmas Foundation aims to disseminate the legacy of the Armenian composer. Recently, the composer’s works have been experiencing a revival, thanks to the efforts of pianist Armen Babakhanian.

Style

Stéphan Elmas began composing near the end of the romantic period. It is no wonder why it is easy to hear influences of Chopin and Grieg in his music, especially in his piano concertos. But there are also a lot of characteristics in his music that are unique to him.

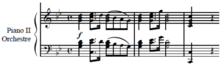

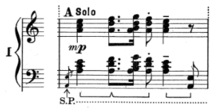

Elmas composed using standard forms, but altering them in his own way. He often expanded rather than contracted formal structures. The first movements of his first and third piano concertos are about 20 minutes long, as played by pianist Armnen Babakhanian. The development section in his third piano concerto is 104 measures, more than 25% of the piece’s 396 measure length. There are many ways that he expanded the form of his first piano concerto, including adding a five measure introduction to the full introduction, having a cadenza at the end of both the exposition and recap, as well as shorter cadenza-like passages at the end of the introduction and development sections, and by returning to the theme from the introduction after the orchestra’s final coda. His third piano concerto also includes an introduction, a cadenza at the end of the exposition and recap, and an additional return to the introduction material in measure 390 after the orchestra’s final coda. His concerto forms also show his added focus on the soloist, as he often doesn’t give a full statement of a theme to the orchestra, as he doesn’t give a full statement of his theme 1 or theme 3 to the orchestra in his first concerto, or a full statement of his first or second themes to the orchestra in his third concerto.

Elmas also often expanded his phrase structure. One of the ways that he did this was simply by repeating phrases, with slight variation. He does this all over his first concerto, such as with this Theme 1 beginning in measure 26 and then repeating it in measure 36. In his third concerto, he does this in his second transition that begins in measure 101, and repeats the small phrase, that is from measures 101-103, four times, with slight variation. Another way is by additionally expanding the repeated phrase portion of a repeated phrase instead of cadencing around the same length of the first phrase by creating a new harmonic sequence based off a motive from the previous theme or elongating the melody. One example of this is in his second theme of his first piano concerto, beginning in measure 110, with a 6 + 6 measure repeated phrase, then repeating this phrase in a smaller 4 measure phrase form across an 18 measure larger phrase.

Stephen Elmas was not afraid to explore new key progressions and structures. For example, in his First piano concerto, he preferenced individualized resolution on a larger scale structure rather than resolving everything to a single unified key, such that in the exposition, he set the introduction in g minor, Theme 1 in g minor, Theme 2 in F major, and Theme 3 in C major, and then in the recap, instead of bringing every theme back to the tonic of g minor, he simply resolves Theme 2 and Theme 3 as if their key in the exposition were a secondary dominant of it in the recap, such that in the recap, Theme 1 is in g minor, Theme 2 is in Bb major, Theme 3 is in F major, but he concludes the piece with the tonic key of g minor with a return to the introduction material. He does a similar thing in his first barcarolle, beginning in Eb minor, climaxing in Eb major in measures 141-156, but then falling back to Eb minor with the opening thematic idea.

Elmas sometimes likes to experiment with various musical modes. His seventh nocturne begins like it is in C# Phrygian mode, sounding like C# minor, but with a lowered second scale degree. The first melodic note is a g#, adding to this harmonic feel. The first notes in the bass also begins with the notes b-a-g#, adding an additional feel of the lowered second as if the tonic were G# Phrygian. This also shows his use of the naturally lowered seventh scale degree, b. This is short lived as it resolves to f# minor. This piece moves to the parallel key of A major, but then moves to the strangely related key of Ab major, a half step lower, bringing back the half-step feel from scale degrees 5-6 in the key of C# Phrygian. Ab major is hard to conceive of from the key of F# minor, as it is the enharmonic second scale degree. His fourth polonaise is set in F# major, a rare key in itself. But he then plays with Bb major in a middle section beginning in measure 57. This could also be the key of Eb minor, as he goes to an eb chord quickly, and then sets a long descending scale-like passage in this harmony. He also goes to Eb major. None of these keys are easily related to the tonic key of F# major, but Eb minor is the enharmonic vi of F# major, and he uses this chord to fall to Db major, the enharmonic V, to return to F# major .

Elmas often embellished his themes by using ornaments or by repeating notes when other composers would simply tie two notes or lengthen the note value. One of his themes that contains an ornament is the introduction theme in his third piano concerto, with an ornament on beat 3 in the first measure and a different ornament on beat three of the second measure of the 3-measure thematic idea. One example of a repeated note is in Theme 1 of his third concerto, which is based on the introduction theme, and instead of making beat one a half note or tying the quarter note to the following eighth note, he decided to repeat the note from beat on again on beat two. The first theme in his third mazurka in Bb major is embellished by chromatic passing tones, a repeated note at the beginning of measure 3, a grace note in measure 3, and a turning figure in measure 8. Theme 2 in his fourth mazurka is made of a single note that repeats 3 times (plays 4 times total), beginning in measure 21. His fifth mazurka also contains a repeating note pattern in its first theme, playing a note two times in a row, beginning in measure 2.

It is also easy to see influence by other composers in his themes. Theme 2 in his third concerto bears a striking resemblance to Edvard Greige’s first theme in his piano concerto in a minor.

He also related themes that were from other compositions of his. One example of this is in the orchestra coda of his third piano concerto, where I believe he is finally allowing the orchestra to play a modified version of the first theme from his first piano concerto.

It is sometimes difficult to determine exactly where Elmas’ themes begin. Looking at his first concerto, the first five measures are a short thematic idea shared between the orchestra and piano solo, only to then be developed into a full length theme that could possibly be considered Theme 1 instead of an introduction theme. In his Barcarolle No. 1, a 2-measure solo bass line in the piano has a nice rising arc, but remains in the tonic key for the first for measures. When it finally moves to the next chord, Bb major, a possible melody begins in the treble clef, but this is the dominant key, and the left hand accompaniment started four measures earlier.

Compositions

Piano with orchestra

- Piano Concerto No. 1 in G minor, 1882

- Piano Concerto No. 2, 1887 (published 1923 or earlier)[5]

- Piano Concerto No. 3, 1900

- Andante cantabile et rondo pastorale

- Youth Concerto (not orchestrated; dedicated to Anton Rubinstein)

String orchestra

- Nocturne No. 4

- Romance

Piano (selected)

- 1 Arabesque

- 2 Aubades, Ballade, 2 Chansons, 2 Chants, Complainte,[6] Eglogue, Elégie,[7] Idylle, Ode, Romance, Sonnet, Stances[8] (all dedicated to Victor Hugo)

- 2 Ballades

- 2 Barcarolles

- 2 Berceuses

- 2 Boleros

- 5 Dances Armeniennes

- 6 Etudes (dedicated to Franz Liszt) (published 1884 by Wetzler of Wien)[9]

- 1 Fantaisie

- 1 Fantaisie – Mazurka

- 2 Impromptus

- 1 Impromptu – Mazurka

- 1 Marche Funèbre

- 27 Mazurkas

- 7 Nocturnes

- 6 Polonaises

- 1 Polonaise – Fantaisie

- 25 Preludes

- 1 Rondo

- 2 Scherzos

- 4 Sonatas (no.1 in B minor published 1923 or earlier[5])

- 9 Valses

Chamber music

Vocal music

- L'Arménie Martyre

- Offrande

References

- Բրուտյան, Ցիցիլիա։ Սփյուռքի հայ երաժիշտները։ «Հայաստան» հրատարակչություն, Yerevan, 1968, pp 240 – 248.

- see also de:Anton Door

- Rapin, Simone. A propos d'Aimée Rapin, peintre sans bras. Édition Musée de Payerne, Payerne, 1977.

- http://www.geneve-tourisme.ch/?rubrique=0000000166&lang=_eng

- Hofmeisters Monatsberichte. Leipzig: Friedrich Hofmeister. May 1923. p. 74. Retrieved June 14, 2014.

- fr:Complainte

- fr:Élégie

- Stanza

- Hofmeisters Monatsberichte. Leipzig: Friedrich Hofmeister. July 1884. p. 184. Retrieved June 14, 2014.

- Hofmeisters Monatsberichte. Leipzig: Friedrich Hofmeister. July 1923. pp. 110–111. Retrieved June 14, 2014. Collection of publications of Elmas works released in 1923 by Steingräber-Verlag of Leipzig, some co-published with Schlesinger of Berlin ("e. Schl.").