Specific performance

Specific performance is an equitable remedy in the law of contract, whereby a court issues an order requiring a party to perform a specific act, such as to complete performance of the contract. It is typically available in the sale of land law, but otherwise is not generally available if damages are an appropriate alternative. Specific performance is almost never available for contracts of personal service, although performance may also be ensured through the threat of proceedings for contempt of court.

| Equitable doctrines |

|---|

|

| Doctrines |

| Defences |

| Equitable remedies |

|

| Related |

Specific performance is commonly used in the form of injunctive relief concerning confidential information or real property. While specific performance can be in the form of any type of forced action, it is usually to complete a previously established transaction, thus being the most effective remedy in protecting the expectation interest of the innocent party to a contract. It is usually the opposite of a prohibitory injunction, but there are mandatory injunctions that have a similar effect to specific performance.

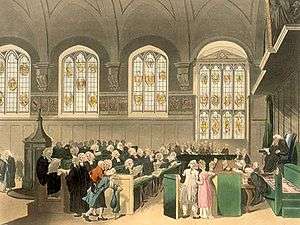

At common law, a claimant's rights were limited to an award of damages. Later, the court of equity developed the remedy of specific performance instead, should damages prove inadequate. Specific performance is often guaranteed through the remedy of a right of possession, giving the plaintiff the right to take possession of the property in dispute.

As with all equitable remedies, orders of specific performance are discretionary, so their availability depends on its appropriateness in the circumstances. Such order are granted when damages are not an adequate remedy and in some specific cases such as land (which is regarded as unique).

Exceptional circumstances

| Contract law |

|---|

|

| Part of the common law series |

| Contract formation |

| Defenses against formation |

| Contract interpretation |

| Excuses for non-performance |

| Rights of third parties |

| Breach of contract |

| Remedies |

| Quasi-contractual obligations |

| Related areas of law |

| Other common law areas |

An order of specific performance is generally not granted if any of the following is true:

- Specific performance would cause severe hardship to the defendant.

- The contract was unconscionable.

- Common Law damages are readily available or the detriment suffered by the claimant is easy to substitute, then damages are adequate.[1][2]

- The claimant has misbehaved (unclean hands).

- Specific performance is impossible.

- Performance consists of a personal service [3]

- The contract is too vague to be enforced.

- The contract was terminable at will (meaning either party can renege without notice).

- Note that consumer protection laws may disallow terms that allow a company to terminate a consumer contract at will (e.g. Unfair Terms in Consumer Contracts Regulations 1999[4])

- The contract required constant supervision.[5]

- Mutuality was lacking in the initial agreement of the contract.

- The contract was made for no consideration.

- Specific performance will not be granted for contracts which are void or unenforceable. The exception to this (in equity) is in relation estoppel or part performance.[6]

- Where an injunction to restrain an employee from working for a rival employer will be granted even though specific performance cannot be obtained. The leading case is Lumley v Wagner, which is an English decision.[7]

Additionally, in England and Wales, under s. 50 of the Senior Courts Act 1981, the High Court has a discretion to award a claimant damages in lieu of specific performance (or an injunction). Such damages will normally be assessed on the same basis as damages for breach of contract, namely to place the claimant in the position he would have been had the contract been carried out.

Examples

In practice, specific performance is most often used as a remedy in transactions regarding land, such as in the sale of land where the vendor refuses to convey title. The reason being that land is unique and that there is not another legal remedy available to put the non-breaching party in the same position had the contract been performed.

However, the limits of specific performance in other contexts are narrow. Moreover, performance based on the personal judgment or abilities of the party on which the demand is made is rarely ordered by the court. The reason behind it is that the forced party will often perform below the party's regular standard, when it is in the party's ability to do so. Monetary damages are usually given instead.

Traditionally, equity would only grant specific performance with respect to contracts involving chattels where the goods were unique in character, such as art, heirlooms, and the like. The rationale behind this was that with goods being fungible, the aggrieved party had an adequate remedy in damages for the other party's non-performance.

In the United States, Article 2 of the Uniform Commercial Code displaces the traditional rule in an attempt to adjust the law of sales of goods to the realities of the modern commercial marketplace. If the goods are identified to the contract for sale and in the possession of the seller, a court may order that the goods be delivered over to the buyer upon payment of the price. This is termed replevin. In addition, the Code allows a court to order specific performance where "the goods are unique or in other proper circumstances", leaving the question of what circumstances are proper to be developed by case law. The relief of Specific Performance is an equitable relief which is usually remedial or protective in nature. In the civil law (the law of continental Europe and much of the non English speaking world) specific performance is considered to be the basic right. Money damages are a kind of "substitute specific performance." Indeed, it has been proposed that substitute specific performance better explains the common law rules of contract as well, see (Steven Smith, Contract Law, Clarenden Law ).

In English law, in principle reparation must be done in specie unless another remedy is ‘more appropriate’.[8]

Legal Debate

There is an ongoing debate in the legal literature regarding the desirability of specific performance. Economists, generally, take the view that specific performance should be reserved to exceptional settings, because it is costly to administer and may deter promisors from engaging in efficient breach. Professor Steven Shavell, for example, famously argued that specific performance should only be reserved to contracts to convey property and that in all other cases, money damages would be superior.[9] In contrast, many lawyers from other philosophical traditions take the view that specific performance should be preferred as it is closest to what was promised in the contract.[10] There is also uncertainty arising from empirical research whether specific performance provides greater value to promisees than money damages, given the difficulties of enforcement.[11]

See also

| Judicial remedies |

|---|

| Legal remedies (Damages) |

| Equitable remedies |

|

| Related issues |

|

- Damages

- Equitable remedy

- Tort

- Clyatt v. United States, 197 U.S. 207 (1905) no specific performance on employment contracts

- Beswick v Beswick

- Tamplin v James

References

- Dougan v Ley [1946] HCA 3, (1946) 71 CLR 142, High Court (Australia).

- Loan Investment Corporation of Australasia v Bonner [1969] UKPC 33 [1969] NZPC 1, [1970] NZLR 724, Privy Council (on appeal from New Zealand).

- Patrick Stevedores Operations No 2 Pty Ltd v Maritime Union of Australia [1998] HCA 32, (1998) 195 CLR 1 (4 May 1998), High Court (Australia).

- (c)making an agreement binding on the consumer whereas provision of services by the seller or supplier is subject to a condition whose realisation depends on his own will alone, http://www.legislation.gov.uk/uksi/1999/2083/schedule/2/made

- Co-Operative Insurance Society Ltd v Argyll Stores (Holdings) Ltd [1997] UKHL 17, [1998] AC 1, House of Lords (UK).

- Goldsbrough, Mort and Co Ltd v Quinn [1910] HCA 20, (1910) 10 CLR 674, High Court (Australia).

- Lumley v Wagner [1852] EWHC J96 (Ch), (1852) 64 ER 1209, High Court of Chancery (England and Wales).

- Beswick v Beswick [1967] UKHL 2, [1968] AC 58, House of Lords (UK) per Lord Pearce.

- Shavell, Steven (2005-11-01). "Specific Performance versus Damages for Breach of Contract". Rochester, NY. SSRN 868593. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Shiffrin, Seana (2007-01-24). "The Divergence of Contract and Promise". Rochester, NY. SSRN 959211. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Arbel, Yonathan A. (2015-01-16). "Contract Remedies in Action: Specific Performance". West Virginia Law Review. SSRN 1641438. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help)

Sources

- A Kronman, ‘Specific Performance’ (1978) 45 University of Chicago LR 351

- S Schwartz, ‘The Case for Specific Performance’ (1979) 89 Yale Law Journal 271

- I Macneil, ‘Efficient Breach of Contract: Circles in the Sky’ (1982) 68 Virginia LR 947