Sparring

Sparring is a form of training common to many combat sports. Although the precise form varies, it is essentially relatively 'free-form' fighting, with enough rules, customs, or agreements to minimize injuries. By extension, argumentative debate is sometimes called sparring.

Differences between styles

The physical nature of sparring naturally varies with the nature of the skills it is intended to develop; sparring in a striking art such as Chun Kuk Do will normally begin with the players at opposite sides of the ring and will be given a point for striking the appropriate area and will be given a foul for striking an inappropriate area or stepping out of the ring. Sparring in a grappling art such as judo might begin with the partners holding one another and end if they separate.

The organization of sparring matches also varies; if the participants know each other well and are friendly, it may be sufficient for them to simply play, without rules, referee, or timer. If the sparring is between strangers, there is some emotional tension, or if the sparring is being evaluated, it may be appropriate to introduce formal rules and have an experienced martial artist supervise or referee the match.

In some schools, permission to begin sparring is granted upon entry. The rationale for this decision is that students must learn how to deal with a fast, powerful, and determined attacker. In other schools, students may be required to wait a few months, for safety reasons,[1] because they must first build the skills they would ideally employ in their sparring practice.

Sparring is normally distinct from fights in competition, the goal of sparring normally being the education of the participants.

Use and sport

The educational role of sparring is a matter of some debate. In any sparring match, precautions of some sort must be taken to protect the participants. These may include wearing protective gear, declaring certain techniques and targets off-limits, playing slowly or at a fixed speed, forbidding certain kinds of trickery, or one of many other possibilities. These precautions have the potential to change the nature of the skill that is being learned. For example, if one were to always spar with heavily padded gloves, one might come to rely on techniques that risk breaking bones in one's hand. Many schools recognize this problem but value sparring nonetheless because it forces the student to improvise, to think under pressure, and to keep their emotions under control.

The level of contact is also debated, lighter contact may lead to less injuries but hard contact may better prepare individuals for competition or self-defense. Some sport styles, such as sanda, taekwondo, tang soo do, Kyokushin kaikan, kūdō, karate, kendo, and mixed martial arts use full contact sparring, though some of them, such as taekwondo (WT) and kendo make use of full-body protective gear.

Brazilian Jiu Jitsu

Brazilian Jiu Jitsu sparring is full contact and injuries are rare as it does not involve striking but rather forcing the opponent to submit using grappling techniques.

MMA

There is much controversy in mixed martial arts about the benefits of full contact sparring vs career threatening injuries. Former Ultimate Fighting Championship fighter Jamie Varner came to an early retirement because he had much head trauma in full contact sparring.[2]

UFC former welterweight champions Robbie Lawler and Johny Hendricks don't do full contact sparring.[3]

Names and types

Sparring has different names and different forms in various schools. Some schools prefer not to call it sparring, as they feel it differs in kind from what is normally called sparring.

- In Western fencing, including historical fencing, the combat is called in English "free play," "sparring," the "assault," or simply "fencing," depending on the form of fencing studied.

- In Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu sparring is commonly called rolling.

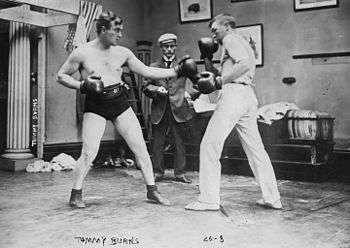

- In boxing, sparring is commonly called sparring.

- In capoeira, the closest analogue to sparring is jogo (playing in the roda).

- In Chinese martial arts, sparring is usually trained at first as individual applications, eventually combined as freestyle training of long, medium and short range techniques. See sanshou, pushing hands.

- In many Japanese martial arts, a grappling-type sparring activity is usually called randori.

- In judo, this is essentially one-on-one sparring.

- In most forms of aikido it is a formalized form of sparring where one aikidoka defends against many attackers.

- In karate, sparring is called kumite (組手)[4], see also randori.

- In kūdō is called sparring

- In taekwondo, sparring is called kyorugi by the World Taekwondo Federation (WTF) or matsogi by the International Taekwon-Do Federation (ITF).

- In the WTF, the majority of the attacks executed are kicking techniques, whereas the ITF encourages the use of both hands and feet. The ITF does not always spar with head guards, but it is known to occur in some organizations practicing this form.

- In silat, the act of sparring may either be referred to as berpencak or bersilat. Another form of competition is silat pulut in which the pracitioners take turns reversing each other's moves.

- In the Indian martial art, Shastarvidya, sparring is done in the form of martial games called Sonchi. The level changes from indicating strikes, to touches and in advanced level, landing full contact blows. However, caution is always maintained in order to avoid any kind of injury or trauma.

See also

References

- "Why Are White Belt Fighters So Dangerous?".

- Hauser, Steve (24 March 2015). "Former UFC fighter Jamie Varner warns young fighters: Too much sparring can lead to early retirement". Bloody Elbow. Retrieved 10 August 2017.

- Matthew Ryder (16 March 2014). "Johny Hendricks vs. Robbie Lawler: How Safe Sparring May Change Contact Sports". Bleacher Report. Retrieved 10 August 2017.

- Stewart, John (Nov 1980), "Kumite: A Learning Experience" (PDF), Black Belt magazine: 28–34, 91