South Great George's Street

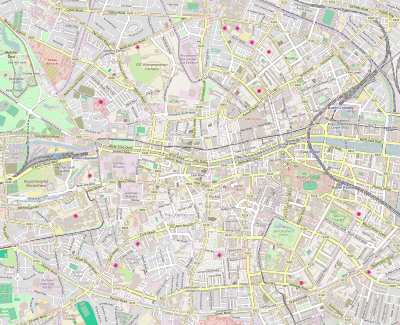

South Great George's Street is a street in Dublin, Ireland.[1]

| |

| |

| Native name | Sráid Sheoirse Mhór Theas (Irish) |

|---|---|

| Namesake | St. George's Church |

| Length | 300 m (1,000 ft) |

| Width | 18 metres (59 ft) |

| Location | Dublin, Ireland |

| Postal code | D02 |

| Coordinates | 53.342792°N 6.264444°W |

| north end | Dame Street |

| south end | Aungier Street, Stephen Street |

| Other | |

| Known for | George's Street Arcade, The George gay community, restaurants |

History

.jpg)

The area is associated with Early Scandinavian Dublin; four burials excavated near South Great George's Street were also associated with domestic habitations, suggesting that the deceased had been members of a settled Norse community and not the fatalities suffered by a transient raiding party. It is thought that South Great George's Street follows the course of an early medieval route – or possibly even the eastern boundary of a longphort, assuming that there was a naval encampment along the eastern shore of the Black Pool at some stage in the settlement's early history.[2]

The street was originally called George's Lane and takes its name from a church dedicated to Saint George, which stood here in 1181. The church was rebuilt in 1213 and stood until 1586.

The Castle Market was held here in the 18th century. The Dublin Lying-In Hospital was founded on George's Lane in 1745, the first maternity hospital in Great Britain or Ireland; it would later become the Rotunda Hospital. In 1765, George's Lane hosted the first exhibition by the Society of Dublin Artists.[3]

In the 1780s, the street was rebuilt by the Wide Streets Commission and renamed South Great George's Street (the name distinguishes it from North Great George's Street, located on the Northside).

During Queen Victoria's infamous 1849 visit, shortly after the Great Famine, a pharmacist on South Great George's Street flew a black flag with a crownless harp and black banners with the words "Famine" and "Pestilence"; these were removed by the Dublin Metropolitan Police.[4]

The South City Markets (today George's Street Arcade) opened in 1881.[5][6][7] Bewley's café opened in 1894.

In the 20th century the street became popular with homosexuals, despite homosexuality being illegal.[8] The George, Dublin's premier gay bar, opened in 1985 and has become a centre of the LGB community.[9] The Dragon, a rival, opened in 2006.[10]

Cultural depictions

South Great George's Street appears several times in the work of James Joyce:

He paid twopence halfpenny to the slatternly girl and went out of the shop to begin his wandering again. He went into Capel Street and walked along towards the City Hall. Then he turned into Dame Street. At the corner of George’s Street he met two friends of his and stopped to converse with them. He was glad that he could rest from all his walking. His friends asked him had he seen Corley and what was the latest. He replied that he had spent the day with Corley. His friends talked very little. They looked vacantly after some figures in the crowd and sometimes made a critical remark. One said that he had seen Mac an hour before in Westmoreland Street. At this Lenehan said that he had been with Mac the night before in Egan’s. The young man who had seen Mac in Westmoreland Street asked was it true that Mac had won a bit over a billiard match. Lenehan did not know: he said that Holohan had stood them drinks in Egan’s.

He left his friends at a quarter to ten and went up George’s Street. He turned to the left at the City Markets and walked on into Grafton Street.

He had been for many years cashier of a private bank in Baggot Street. Every morning he came in from Chapelizod by tram. At midday he went to Dan Burke’s and took his lunch—a bottle of lager beer and a small trayful of arrowroot biscuits. At four o’clock he was set free. He dined in an eating-house in George’s Street where he felt himself safe from the society of Dublin’s gilded youth and where there was a certain plain honesty in the bill of fare. His evenings were spent either before his landlady’s piano or roaming about the outskirts of the city. His liking for Mozart’s music brought him sometimes to an opera or a concert: these were the only dissipations of his life.

[…]

One of his sentences, written two months after his last interview with Mrs Sinico, read: Love between man and man is impossible because there must not be sexual intercourse and friendship between man and woman is impossible because there must be sexual intercourse. He kept away from concerts lest he should meet her. His father died; the junior partner of the bank retired. And still every morning he went into the city by tram and every evening walked home from the city after having dined moderately in George’s Street and read the evening paper for dessert.

Three and eleven she paid for those stockings in Sparrow’s of George’s street on the Tuesday, no the Monday before Easter and there wasn’t a brack on them and that was what he was looking at, transparent, and not at her insignificant ones that had neither shape nor form (the cheek of her!) because he had eyes in his head to see the difference for himself.

Annie Sparrow's shop was located at 16 South Great George's Street.[13]

What also stimulated him in his cogitations?

The financial success achieved by Ephraim Marks and Charles A. James, the former by his 1d bazaar at 42 George’s street, south, the latter at his 6 1/2d shop and world’s fancy fair and waxwork exhibition at 30 Henry street, admission 2d, children 1d: and the infinite possibilities hitherto unexploited of the modern art of advertisement if condensed in triliteral monoideal symbols, vertically of maximum visibility (divined), horizontally of maximum legibility (deciphered) and of magnetising efficacy to arrest involuntary attention, to interest, to convince, to decide.

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to South Great George's Street, Dublin. |

References

- Kelly, Olivia. "Hotel approved for long-derelict South Great George's Street building". The Irish Times.

- Clarke, H. B. (2005). Irish Historic Towns Atlas, No. 11. Dublin: Royal Irish Academy. ISBN 1-874045-89-5.

- Gilbert, Sir John Thomas (February 23, 1861). "A History of the City of Dublin". J. Duffy – via Google Books.

- Dickson, David (November 17, 2014). "Dublin: The Making of a Capital City". Harvard University Press – via Google Books.

- "HP13 South Great George's St | Dublin City Council". www.dublincity.ie.

- "South Great George's Street - Market Buildings | Dublin city, Dublin, Building". Pinterest.

- "George's Street Arcade".

- "UVF had no need of British collusion for Dublin and Monaghan atrocities". Sunday Independent. Retrieved on 8 April 2007. "The Garda report found that the man was a 'homosexualist' and was in Dublin because he liked to frequent establishments in South Great George's Street popular with gay men at the time".

- "Street Style: South Great George's Street". June 17, 2014.

- "The George & The Dragon on the Market • GCN". GCN. May 28, 2014.

- "Dubliners, by James Joyce". www.gutenberg.org.

- "Ulysses, by James Joyce". www.gutenberg.org.

- "Libraries and Archive - 1899 and 1908 to 1915 Electoral Rolls". databases.dublincity.ie.