Social penetration theory

The social penetration theory (SPT) proposes that, as relationships develop, interpersonal communication moves from relatively shallow, non-intimate levels to deeper, more intimate ones.[1] The theory was formulated by psychologists Irwin Altman and Dalmas Taylor in 1973 to understand relationship development between individuals. Altman and Taylor note that relationships "involve different levels of intimacy of exchange or degree of social penetration". SPT is known as an objective theory as opposed to an interpretive theory, meaning that it is based on data drawn from experiments and not from conclusions based on individuals' specific experiences.[2]

SPT states that the relationship development occurs primarily through self-disclosure, or intentionally revealing personal information such as personal motives, desires, feelings, thoughts, and experiences to others. This theory is also guided by the assumptions that relationship development is systematic and predictable. Through self-disclosure, relationship development follows particular trajectory, moving from superficial layers of exchanges to more intimate ones.[1] Self-disclosure is the major way to bring a relationship to a new level of intimacy. SPT also examines the process of de-penetration and how some relationships regress over time and eventually end.[3]

Assumptions

SPT is based on four basic assumptions.[4]

- Relationship development moves from superficial layers to intimate ones.

- For instance, on a first date, people tend to present their outer images only, talking about hobbies. As the relational development progresses, wider and more controversial topics such as political views are included in the conversations.

-

- Interpersonal relationships develop in a generally systematic and predictable manner.

- This assumption indicates the predictability of relationship development. Although it is impossible to foresee the exact and precise path of relational development, there is certain trajectory to follow. As Altman and Taylor note, "People seem to possess very sensitive tuning mechanisms which enable them to program carefully their interpersonal relationships."[1]

-

- Relational development could move backward, resulting in de-penetration and dissolution.

- For example, after prolonged and fierce fights, a couple who originally planned to get married may decide to break up and ultimately become strangers.

-

- Self-disclosure is the key to facilitate relationship development.

- Self-disclosure means disclosing and sharing personal information to others. It enables individuals to know each other and plays a crucial role in determining how far a relationship can go, because gradual exploration of mutual selves is essential in the process of social penetration.[1]

Self-disclosure

The self-disclosure is a purposeful disclosure of personal information to another person.[5] Disclosure may include sharing both high-risk and low-risk information as well as personal experiences, ideas, attitudes, feelings, values, past facts and life stories, and even future hopes, dreams, ambitions, and goals. In sharing information about themselves, people make choices about what to share and with whom to share it. Altman and Taylor believe that opening inner self to other is the main route to reach to intimate relationships.

As for the speed of self-disclosure, Altman and Taylor were convinced that the process of social penetration moves quickly in the beginning stages of a relationship and slows down considerably in the later stages. Those who are able to develop a long-term, positive reward/cost outcome are the same people who are able to share important matches of breadth categories. The early reward/cost assessment have a strong impact on the relationship's reactions and involvement, and expectancies in a relationship regarding the future play a major role on the outcome of the relationship.

Disclosure reciprocity

Self-disclosure is reciprocal, especially in the early stages of relationship development. Disclosure reciprocity is an indispensable component in SPT.[4] Disclosure reciprocity is a process in which when one person reveals personal information of a certain intimacy level, the other person will in turn disclose information of the same level.[6] It is two-way disclosure, or mutual disclosure. Disclosure reciprocity can induce positive and satisfactory feelings and drive forward relational development. This is because as mutual disclosure take place between individuals, they might feel a sense of emotional equity. Disclosure reciprocity occurs when the openness of one person is reciprocated with the same degree of the openness from the other person.[4] For instance, if someone was to bring up their experience with an intimate topic such as weight gain or having divorced parents, the person they are talking to could reciprocate by sharing their own experience.[7]

Onion metaphor

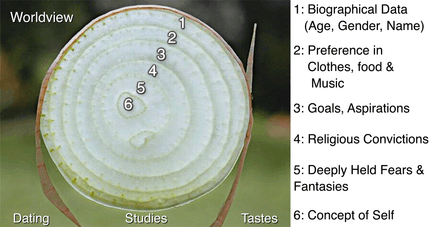

SPT is known for its onion analogy, which implies that self-disclosure is the process of tearing layers or concentric circles away.[4] The onion denotes various layers of personality. It is sometimes called the "onion theory" of personality. Personality is like a multi-layered onion with public self on the outer layer and private self at the core. As time passes and intimacy grows, the layers of one's personality begin to unfold to reveal the core of the person. Three major factors influence self-revelation and begin the process of the onion theory, which are personal characteristics, reward/cost assessments, and the situational context.[8]

Stages

The development of relationship is not automatic but rather occurs through the skills of partners in revealing or disclosing first their attitudes and later their personalities, inner character, and true selves. This is done in a reciprocal manner. The main factor that acts as a catalyst in the development of relationships is proper self disclosure. Altman and Taylor proposes that there are four major stages in social penetration:

-

- Exploratory affective stage

- Individuals start to reveal the inner self bit by bit, expressing personal attitudes about moderate topics such as government and education. This may not be the whole truth as individuals are not yet comfortable to lay themselves bare. This is the stage of casual friendship, and many relationships do not go past this stage.

-

- Affective stage

- Individuals are getting more comfortable to talk about private and personal matter, and there are some forms of commitment in this stage. Personal idioms, or words and phrases that embody unique meanings between individuals, are used in conversations. Criticism and arguments may arise. A comfortable share of positive and negative reactions occurs in this stage. Relationships become more important to both parties, more meaningful and more enduring. It is a stage of close friendships and intimate partners.[4]

-

- Stable stage

- The relationship now reaches a plateau in which some of the deepest personal thoughts, beliefs, and values are shared and each can predict the emotional reactions of the other person. This stage is characterized with complete openness, raw honesty and a high degree of spontaneity.[4]

- De-penetration stage (optional)

- When the relationship starts to break down and costs exceed benefits, then there is a withdrawal of disclosure which causes the relationship to end.[9]

De-penetration

De-penetration is a gradual process of layer-by-layer withdrawal and it cause relationship and intimacy level to move backward and fade away. According to Altman and Taylor, when de-penetration occurs, "interpersonal exchange should proceed backwards from more to less intimate areas, should decrease in breadth or volume, and, as a result, the total cumulative wedge of exchange should shrink".[1] A warm friendship between two people will deteriorate if they begin to close off areas of their lives that had earlier been opened. Relational retreat takes back of what has earlier been exchanged in the building of a relationship. Relationships are likely to break down not in an explosive argument but in a gradual cooling off of enjoyment and care. What is worth noting is that Tolstedt and Stokes finds that in the de-penetration process, the self-disclosure breadth reduces, while self-disclosure depth increases.[10] It is because when intimate relationship is dissolving, a wide range of judgments, feelings and evaluations, particularly the negative ones, are involved in conversations.[10]

Idiomatic communication in self-disclosure

Within the coming together and falling apart stages of a relationship, partners will oftentimes use unique forms of communication, such as nicknames and idioms, to refer to one another. This is known as idiomatic communication, a phenomenon that is reported to occur more often among couples in the coming together stages of a relationship.[11] Couples that find themselves falling apart reported that idiomatic communication, which can include teasing insults and other personally provocative language, overall have an adverse effect on the relationship as a whole. Therefore, this personalized form of communication acts more as a maintainer of a relationship and is not to be necessarily taken as a sign that a couple is moving upward or downward in their relationship trajectory.

Breadth and depth

Both depth and breadth are related to the onion model. As the wedge penetrates the layers of the onion, the degree of intimacy (depth) and the range of areas in an individual's life that an individual chooses to share (breadth) increases.

(1) Breadth

The breadth of penetration is the range of areas in an individual's life being disclosed, or the range of topics discussed. For instance, one segment could be family, a specific romantic relationship, or academic studies. Each of these segments or areas are not always accessed at the same time. One could be completely open about a family relationship while hiding an aspect of a romantic relationship for various reasons such as abuse or disapproval from family or friends. It takes genuine intimacy with all segments to be able to access all areas of breadth at all times.[12]

(2) Depth

The depth of penetration is a degree of intimacy. This does not necessarily refer to sexual activity, but how open and close someone can become with another person despite their anxiety over self-disclosure. Doing this will give the person more trust in the relationship and make them want to talk about deeper things that would be discussed in normal, everyday conversation. This could be through friendship, family relationships, peers, and even romantic relationships with either same-sex or opposite-sex partners.

When talking with one person over time, someone could make more topics to talk about so the other person will start to open up and express what they feel about the different issues and topics. This helps the first person to move closer to getting to know the person and how they react to different things. This is applicable when equal intimacy is involved in friendship, romance, attitudes and families.

(3) Relationship

It is possible to have depth without breadth and even breadth without depth. For instance, depth without breadth could be where only one area of intimacy is accessed. "A relationship that could be depicted from the onion model would be a summer romance. This would be depth without breadth." On the other hand, breadth without depth would be simple everyday conversations. An example would be when passing by an acquaintance and saying, "Hi, how are you?" without ever really expecting to stop and listen to what this person has to say is common. To get to the level of breadth and depth, both parties have to work on their social skills and how they present themselves to people. They have to be willing to open up and talk to each other and express themselves. One person could share some information about their personal life and see how the other person responds. If they do not want to open up the first time, the first person has to keep talking to the second person and have many conversations to get to the point where they both feel comfortable enough for them to want to talk to each other about more personal topics.

The relationship between breadth and depth can be similar to that used in technology today. Pennington describes in a study that

... With a click of the mouse to accept them as a "friend" roommates across the country can learn: relationships status (single, engaged, it's complicated), favorite movies, books, TV shows, religious views, political views, and a whole lot more if someone takes the time to fill out an entire Facebook profile[13]

Because of social media sites like Facebook, the breadth of subjects can be wide, as well as the depth of those using the platforms. Users of these platforms seem to feel obligated to share simple information as was listed by Pennington, but also highly personal information that can now be considered general knowledge. Because of social media platforms and user's willingness to share personal information, the law of reciprocity is thrown out the window in favor of divulging personal information to countless followers/friends without them sharing the same level of vulnerability in return. In cases like this, there is depth without much breadth.[13]

Barriers

Several factors can affect the amount of self-disclosure between partners: gender, race, religion, personality, social status and ethnic background. For example, Americans friends tend to discuss intimate topics with each other, whereas Japanese friends are more likely to discuss superficial topics.[14] One might feel less inclined to disclose personal information if doing so would violate their religious beliefs. Being part of a religious minority could also influence how much one feels comfortable in disclosing personal information.[15] In romantic relationships, women are more likely to self-disclose than their male counterparts.[16] Men often refrain from expressing deep emotions out of fear of social stigma. Such barriers can slow the rate of self-disclosure and even prevent relationships from forming. In theory, the more dissimilar two people are, the more difficult or unlikely self-disclosure becomes.

Stranger-on-the-train phenomenon

Most of the time individuals engage in self-disclosure strategically, carefully evaluating what to disclose and what to be reserved, since disclosing too much in the early stage of relationship is generally considered inappropriate, which can end or suffocate a relationship. Whereas, in certain contexts, self-disclosure does not follow the pattern. This exception is known as "stranger-on-the-train (or plane or bus)" phenomenon, in which individuals reveal personal information with complete strangers in public spaces rapidly.[4] For instance, on a night coach from London to Paris, two individuals sitting next to each other may start conversation very soon, and somehow a wide range of topics including controversial and very personal ones may be discussed. In such situations, self-disclosure is spontaneous rather than strategic. This specific concept can be known as verbal leakage, which is defined by Floyd as "unintentionally telling another person something about yourself".[17] SPT operates under the impression that the self-disclosure given is not only truthful, meaning the speaker believes what is being said to be true, but intentional.[17] Self-disclosure can be defined as "the voluntary sharing of personal history, preferences, attitudes, feelings, values, secrets, etc., with another person".[18] The information given in any relationship, whether acquaintance or a well-established relationship, should be voluntarily shared, otherwise it does not follow the laws of reciprocity, and would fall under the verbal leakage umbrella, or the stranger-on-the-train phenomenon.[17] It is still a puzzle why such instant intimacy could occur. Some researchers argue that revealing our inner self to complete strangers is deemed as "cathartic exercise" or "service of confession", which allows individuals to unload emotions and express deeper thoughts without being haunted by the potential unfavorable comments or judgements.[19] This is because people tend to take lightly and dismiss responses from strangers, who do not really matter in their lives. Some researcher suggests that this phenomenon occurs because individuals feel less vulnerable to open up to strangers who they are not expected to see again.[20]

Sexual communication anxiety among couples

The rate of sexual satisfaction in relationships has been observed to relate directly to the effective communication between couples. Individuals in a relationship who experience anxiety will find it difficult to divulge information regarding their sexuality and desires due to the perceived vulnerabilities in doing so. In a study published by the Archives of Sexual Behavior, socially anxious individuals generally attribute potential judgement or scrutiny as the main instigators for any insecurities in self-disclosing to their romantic partners.[21] This fear of intimacy, and thus a lower level of sexual self-disclosure within a relationship, is predicted to correlate to a decrease in sexual satisfaction.

Rewards and costs assessment

Social exchange theory

Social exchange theory states that humans weigh each relationship and interaction with another human on a reward cost scale without realizing it. If the interaction was satisfactory, then that person or relationship is looked upon favorably. But if an interaction was unsatisfactory, then the relationship will be evaluated for its costs compared to its rewards or benefits. People try to predict the outcome of an interaction before it takes place. Coming from a scientific standpoint, Altman and Taylor were able to assign letters as mathematical representations of costs and rewards. They also borrowed the concepts from Thibaut and Kelley's in order to describe the relation of costs and rewards of relationships. Thibaut and Kelley's key concepts of relational outcome, relational satisfaction, and relational stability serve as the foundation of Irwin and Taylor's rewards minus costs, comparison level, and comparison level of alternatives.

A major factor of disclosure is an individual calculation in direct relation to benefits of the relationship at hand. Each calculation is unique in its own way because every person prefers different things and therefore will give different responses to different questions.

An example of how rewards and costs can influence behavior is if an individual were to ask another individual on a date. If they accept, then the first individual has gained a reward, making them more likely to repeat this action. However, if they decline, then they have received a punishment which in turn would stop them from repeating an action like that in the future. The more someone discloses to their partner, the greater the intimacy reward will be. When the individuals involved in the relationship hold positive values in this calculation, intimacy proceeds at an accelerated rate. In the relationship, if both parties are dyad, the cost exceeds the rewards. The relationship then will slow considerably, and future intimacy is less likely to happen. The basic formula in which some can process this in most situations is: Behavior (profits) = Rewards of interaction − costs of interaction.

This means that people want to maximize their rewards and minimize their costs when they are in a relationship with somebody. According to Altman and Taylor, relationships are sustained when they are relatively rewarding when the outcome is positive and discontinued when they are relatively costly (when the outcome is negative).

Outcome = Rewards − Costs

A positive result will in return result in more disclosure.

Comparison level

The first standard that we use to evaluate the outcomes of a situation is comparison level (CL). As defined by Thibaut and Kelley, CL is the standard by which individuals evaluate the desirability of group membership. A group is defined as "two or more interdependent individuals who influence one another through social interaction". In this instance, the group refers to a dyadic relationship, but it can really be extended to any type of group. "A person's comparison level (CL) is the threshold above which an outcome seems attractive". That is, when groups fall above the CL they are seen as being satisfying to the individual, and when they fall below the CL they are seen as being unsatisfying. We take an average of outcomes from the past as a benchmark to determine what makes us happy or sad so that we may develop the threshold, or comparison level, in which an outcome appears attractive. Past experiences shape one's thoughts and feelings about developing relationships, and in this way, an individual's CL is very much influenced by these previous relationships.

Comparison level of alternatives

A person's CL is the threshold above which an outcome appears attractive. CL only predicts when we are satisfied with membership in a given relationship, or group. Therefore, Thibaut and Kelley also say that people use a CL for alternatives to evaluate their outcomes. Basically, CL for alternatives is determined by "the worst outcome a person will accept and still stay in a relationship." As such, comparison level for alternatives is a better predictor for whether or not a person will join or leave a relationship, or group. However, even if a relationship is unhealthy, a person might choose to remain in it because it is better than what they perceive the real world to be. Trends and sequences are one of the major factors when evaluating a relationship.

Applications

Interpersonal communication

The value of SPT initially lies in the area of interpersonal communication. Scholars have been using the concepts and onion model to explore the development of counter-sex/romantic relationships, friendships, parent-child relationships, employer-employee relationships, caregiver-patient relationships and beyond. Some of the key findings are described as follows.

Researchers have found out that in parent-child relationships, information derived from the child's spontaneous disclosure in daily activities was most closely connected to generating and maintaining their trust in parents, indicating the importance of developing shallow but broad relationships with children through everyday conversation rather than long-lasting profound lectures (Kerr, Stattin & Trost, 1999). Honeycutt used the SPT model, along with the Attraction Paradigm, to analyze happiness between married couples. While the SPT model believes that relationships are grounded on effective communication, the Attraction Paradigm believes that relationships are grounded on having shared interests, personality types, and beliefs. The results showed that having a perceived understanding of each other can lead to happiness between married couples. While the research notes that it looks only at perceived understanding and not actual understanding, it shows the importance of relationship development. The more that partners in a relationship interact with each other, the more likely they are to have a better understanding of each other.[22] Scholars also use this theory to examine other factors influencing the social penetration process in close friendships. As Mitchell and William (1987) put it, ethnicity and sex do have impact on the friendship foster. The survey results indicates that more breadth of topics occurs in penetration process in black friendship than white.[23] Regarding the caregiver-patient relationship, developing a social penetrated relationship with institution disclosed breadth and depth information and multiple effective penetration strategies is critical to the benefits of the patients (Yin & Lau, 2005). Nurses could apply the theory into daily interactions with patients, as doctors could in their articulations when consulting or announcing.

Gender-based difference in self-disclosure

Research demonstrates that there are significant gender differences in self-disclosure, particularly emotional self-disclosure, or expressing personal feelings and emotions, such as "Sometimes, I feel lonely to study abroad and to be away from my family."[6] Emotional self-disclosure is at core of intimate relationship developments, because unlike factual (descriptive) self-disclosure, or sharing superficial self-relevant facts, such as "I'm studying abroad in Japan", it is more personal and more effective to cultivate intimacy.[24] Emotional self-disclosure makes individuals "transparent" and vulnerable to others.[6] According to previous studies, females are more socially oriented, whereas males are more task-oriented, and thus females are believed to be more socially interdependent than males.[25] This is one of the reasons that contributes to the gender difference in self-disclosure. In a friendship between females, emotional attachments such as sharing emotions, thoughts, experiences, and supports are at the core, while friendships between males tend to focus on activities and companionship.[6] Overall, women's friendships are described as more intimate than men's friendship.

In addition, there is a gender difference regarding to topics revealed. Men tend to disclose their strengths. On the contrary, women disclose their fear more.[6] Both men and women are prone to disclose their emotions to the same-sex friends more, but women are prone to reveal more than men to both same-sex as well as cross-sex friends.[20] What is worth noting is that according to a research conducted among Pakistani students, women extensively disclose their feelings, while emotions such as depression, anxiety and fear are more likely being disclosed to male friends, because men are perceived as more capable to deal with such emotions.[6]

Self-disclosure in the LGBT community

Minority groups especially have a unique way of creating closeness between each other. For example, lesbian friendships and intimate relationships are reliant on mutual self-disclosure and honesty.[26] Both parties must expose themselves for an authentic and genuine relationship to develop. The problem is that for many lesbians, this process is not always as simple as it may seem. Exposing one’s sexual orientation can be a difficult and grueling process and because of this, many lesbians avoid disclosing their true identities to new acquaintances.[26] This leads these individuals to turn to their family members or already existing social support systems, which may lead to a strain in those relationships and a smaller social support system.[26]

Because of these difficulties, lesbians will limit who they choose to surround themselves with. A lot of these women involve themselves in groups that are solely made up of only lesbians or groups that are only made up of heterosexual women to avoid their true lesbian identity.[26]

Authentic communication is built on honest self-disclosure. This part of the relationship process lies heavily on exposing one’s personal values and self-concept.[26] When a relationship is being created, innermost thoughts and feelings are shared and trust is built. It can be difficult for lesbian individuals to open-up about their sexual identities, because of the fear of being rejected or losing special relationships.[26]

A study was done to examine self-disclosure among LGBT youths. Through a series of interviews, a group of LGBT youths described their coming out experiences. They told the interviewers about who they chose to disclose their sexual orientation to and whether the disclosure had a positive or negative effect on their relationships.[27]

Results showed that more youths disclosed their sexual orientation to their friends than to their parents. A number of participants chose to disclose their sexual orientation to their teachers. Results also showed both positive and negative reactions. Some youth expressed de-penetration in their friendships after coming out, as well as de-penetration in their sibling relationships. Some participants expressed experiencing other reactions beside positive and negative. There were invalidated reactions, where a participant’s sexual orientation was dismissed as a “phase” and neutral reactions, where the recipient of the disclosure informed the participant that they were already aware of their sexual orientation. Some participants expressed having mixed and evolving results. For example, a participant who identified as a transgender male said that his mother was initially fine with his sexual orientation, which at the time was a lesbian woman, but had a negative reaction when he later came out as transgender. A few participants mentioned that they had initially received negative reactions from friends and family after coming out, but that as time went on, their sexual orientation came to be accepted and the relationships remained intact.[27]

LGBT professionals often feel anxiety about disclosing their sexual orientation to their colleagues. Professionals who chose to disclose their sexual orientation have had mixed reactions in how it has affected their relationship with their colleagues. Some had had positive reactions, strengthening their relationships and their overall job satisfaction, while others have had the opposite experience. They feel that disclosing their sexual orientation hurt their professional relationships and their overall job satisfaction. The atmosphere of one’s office can influence their decision to disclose their sexual orientation. If their colleagues are themselves LGBT or if they have voiced support for the LGBT community, the more likely they are to disclose their sexual orientation. If they have little to no colleagues who are openly part of the LGBT community or if there is no vocal support, the less likely they are to come out.[28]

Patient self-disclosure in psychotherapy

Patient self-disclosure has been a prominent issue in therapy, particularly in psychotherapy. Early studies have shown that patients' self-disclosure is positively related to treatment outcomes.[20] Freud is a pioneer in encouraging his patients to totally open up in psychotherapy.[20] Many early clinical innovations, such as lying on the couch and therapist's silence, are aimed to create an environment, an atmosphere, that allows patients to disclose their deepest self, and free them from concerns facilitating conscious suppression of emotions or memories.[20] Nonetheless, even with such efforts, as Barry A. Farber puts it, in psychotherapy "full disclosure is more of an ideal than an actuality."[20] Patients are prone to reveal certain topics to the therapists, such as disliked characteristics of self, social activities, as well as relationship with friends and significant ones; while tend to avoid discussing certain issues, such as sexual-oriented experiences, immediately experienced negative reactions (e.g feeling misunderstood or confused) due to conscious inhibition.[20]

In psychotherapy, patients have to deal with the tension between confessional relief and confessional shame all the time.[20] It has been shown that the length of therapy and the strength of the therapeutic alliance, the bond between the patient and the therapist, are two major factors that affect self-disclosure in psychotherapy.[20] As SPT indicates, the longer patients spent time with their therapists, the broader becomes the range of issues being discussed, and more topics are marked with depth.[20] The greater the depth of the discussions, the more likely the patient feels being vulnerable. Therefore, the trust built over time among the patient and the therapist is essential to reach a mode of deep discussion. To strengthen the alliance, cultivating a comfortable atmosphere for self-disclosure and self-discovery is important.[20]

Patient/therapist self-disclosure

The condition of patients’ with eating disorders have been shown to improve with therapist self-disclosure. In 2017, a study was conducted and 120 participants (95% were women) were surveyed.[29] For the purpose of the study, appropriate therapist self-disclosure was defined as sharing positive feelings towards participants in therapy and discussing one's training background.

The results found that 84% of people said their therapist disclosed positive feelings to them while in therapy.[29] The study found that when therapists disclosed positive feelings, it had a positive effect on the patient's eating problems.[29] Eating disorders generally got better with therapist self-disclosure. When the therapist shared self-referent information to the patient it created trust and the patients perceived the therapist as being more "human." Patients with eating disorders saw the therapist disclosure as a strengthening therapeutic relationship.[29] However, personal self-disclosure of the therapist‒sexuality, personal values, and negative feelings‒was considered inappropriate by patients.[29]

Self-disclosure and individuals with social phobia

Social phobia, or social anxiety disorder (SAD), is a disorder in which individuals are experienced with overwhelming levels of fear in social situations and interactions. Individuals with social phobia tend to adopt strategic avoidance of social interactions, which makes it challenging for them to disclose themselves to others and reveal emotions. Self-disclosure is the key to foster intimate relationship, in which individuals can receive needed social supports. Close friendship and romantic relationship are two major sources for social supports, which have protective effect and play a crucial role in helping individuals with social phobia to cope with distress.[30] Due to the profound impacts of the anxiety disorder, it has been found that late marriage or staying unmarried for the lifetime is prevailing among population with social phobia.[30] This is problematic, because being unable to gain needed social supports from intimate ones further confines the social phobic in the loneliness and depression that they have been suffering from.[30] In response to the problem, Sparrevohn and Rapee suggest that improving communication skill, particularly self-disclosure and emotional expression, should be included in future social phobia treatment, so the life quality of individuals with social phobia can be improved.[30]

Server-patron mutual disclosure in restaurant industry

As social penetration theory suggests, disclosure reciprocity induces positive emotion which is essential for retaining close and enduring relationships. In service industry, compared with securing new customers, maintaining long-term relationships with existing customers is more cost-effective.[25] Therefore, engaging with current customers is a crucial topic in restaurant industry. Hwang et al. indicates that mutual disclosure is the vital factor for establishing trust between customers and servers.[31] Effective server disclosure, such as sincere advice about menu choices and personal favorite dishes, can elicit reciprocity of information exchange between servers and customers. The received information regarding to the taste and preference of the customers then can be used to provide tailored services, which in turn can positively strengthen customers' trust, commitment and loyalty toward the restaurant.[25]

Hwang et al. suggest that server disclosure is more effective to evoke customer disclosure in female customers, who are more likely to reveal personal information than their male counterparts.[25] In addition, studies have shown that factors such as expertise (e.g. servers' knowledge and experience), customer-oriented attribute (e.g. listening to the concerns from the customers attentively), as well as marital status influence mutual disclosure in the restaurant setting. Expertise is positively correlated to both customer and server disclosure.[31] Server disclosure is only effective in inducing disclosure and positive feelings from unmarried patrons who are more welcome to have a conversation with the servers.[31]

Organizational communication

The ideas posited by the theory have been researched and re-examined by scholars when looking at organizational communication. Some scholars explored the arena of company policy making, demonstrating that the effect company policies have on the employees, ranging from slight attitudinal responses (such as dissatisfaction) to radical behavioral reactions (such as conflicts, fights and resignation). In this way, sophisticated implementation of controversial policies is required (Baack, 1991). Social penetration theory offers a framework allowing for an explanation of the potential issues.

Media-mediated communication

Self-disclosure in reality TV

Reality TV shows are gaining popularity in the last decades, and the trend is still growing. Reality TV is a genre that is characterized with real-life situations and very intimate self-disclosure in the shows. Self-disclosure in reality show can be considered as self-disclosure by media characters and the relationship between the audience and the media character is parasocial.[32]

In reality show, self-disclosure are usually delivered in the form of a monologue, which is similar real-life self-disclosure and gives the audience the illusion that the messages are directed to them.[32] According to social penetration theory, self-disclosure should follow certain stages, moving from the superficial layers to the central layers gradually. Nonetheless, rapid self-disclosure of intimate layers is a norm in reality TV shows, and unlike in interpersonal interactions, viewers prefer early intimate disclosure and such disclosure leads to liking rather than inducing uncomfortable feeling.[32] Heavy viewers are more accustomed to the norm of early intimate disclosure, because provocative stimuli and voyeuristic are what they are searching for in such shows.[32]

Computer-mediated communication

Computer-mediated communication (CMC) can be thought of as another way in which people can develop relationships. The Internet has been thought to broaden the way people communicate and build relationships by providing a medium in which people could be open-minded and unconventional and circumvent traditional limitations like time and place. (Yum & Hara, 2005)

Some theorists find this concept impossible and there are barriers to this idea. Since there are risks and there is usually more uncertainty about whether the person on the other side of the computer is being real and truthful, or deceitful and manipulative for one reason or another there is no possible way to build a relationship. A lack of face-to-face communication can cause heightened skepticism and doubt. Since this is possible, there is no chance to make a long-lasting and profound connection.

However, there are other researchers who have found that self-disclosure online tends to reassure people that if they are rejected, at least it’s more likely to be by strangers and not family or friends; thus, reinforcing the desire to self-disclose online, rather than face-to-face. (Panos, 2014)[33] Not only are people meeting new people to make friends, but many people are meeting and initiating romantic relationships online. (Yum & Hara, 2005) In another study, it was found that "CMC dyads compensated for the limitations of the channel by making their questions more intimate than those who exhibited face-to-face" (Sheldon, 2009).

Celebrity's self-disclosure on social media

Social media has turned to be a crucial platform for celebrities to engage with their followers. On social medias, the boundaries between interpersonal and mass communication is blurred, and parasocial interaction (PSI) is adopted strategically by celebrities to enhance liking, intimacy and credibility from their followers.[34] As Ledbetter and Redd notes, "During PSI, people interact with a media figure, to some extent, as if they were in an actual interpersonal relationships with the target entity."[34] For celebrities, professional self-disclosure (e.g. information as to upcoming events) and personal self-disclosure (e.g. emotions and feelings) are two primary ways to cultivate illusory intimacy with their followers and to expand their fan bases. What is worth noting is that unlike in real-life interpersonal relationship, disclosure reciprocity is not expected in parasocial interactions, although through imagined interactions on social medias, followers do feel they are connected to the media figures.[24]

Social networking

Self-disclosure has been studied when it comes to face-to-face interactions. Since social networking sites are relatively new phenomena, there are not as many studies done about how people disclose information online compared to a one-on-one interaction. There have been surveys conducted about how social networking sites such as Facebook, MySpace, Twitter, LinkedIn, hi5, myyearbook, or Friendster affect interactions between human beings. On Facebook, users are able to determine their level and degree of self-disclosure by setting their privacy settings (McCarthy, 2009).[35] People achieve the breadth via posting about their everyday lives and sharing surface information while developing intimate relationships with great depth by sending private Facebook messages and creating closed groups.

The level of intimacy that one chooses to disclose as part CMC depends on the type of website they are using to communicate. Disclosing personal information online is a goal-oriented process. If one’s goal is to build a relationship with someone, they would likely disclose personal information over instant messaging (IM) and on social media. It is highly unlikely that they would choose to share that information in a website that is used for online shopping. With online shopping, the goal is to make a purchase and not to build a relationship. Thus, the individual would share only the information needed (i.e. name and address) in order to make a purchase. In disclosing information over IM and in social media, the individual is much more selective in what they choose to disclose.[36]

There was a study done about the connection on how couples or other romantic relationships have trust, commitment, and affection towards each other and the amount of self-disclosure each person gives to the one another. There are several criteria to the study. One important is how the couple met. If they met before talking over the Internet, they are more likely to reveal personal information due to the higher levels of trust. According to Rempel, Holmes, & Zanna (1985) the best way to be able to trust someone is to be able to foretell or calculate how another person will act or react to any given information. In other words, we are more probable to release information about ourselves if we can predict the behavior of the other person.

"The hyperpersonal perspective suggests that the limited cues in CMC are likely to result in over attribution and exaggerated or idealized perceptions of others and that those who meet and interact via CMC use such limited cues to engage in optimized or selective self-presentation". (Walther, 1996) In other words, there could be deceitful or dishonest intents involved from people on the Internet. There is the possibility that someone could mislead another person because there are more opportunities to build a more desirable identity without fear of persecution. If there is no chance of ever meeting the person on the other end of the computer, then there is a high risk of falsifying information and credentials.

Other theorists such as Rubin and Bargh say that because of the blockade of the computer, it increases how likely people are to be true and honest about themselves. There is also the idea that there will not be any fear of consequences for less than respectable decisions made in the past. Computer-mediated communication has also been thought to even speed up the intimacy process because computers allow individual communication to be more, rather than less, open and accommodating about the characteristics of the person or persons involved. Both ideas and types of theories can be proven and disproven, but it all depends on how an individual uses and or abuses computer-mediated communication.

Research has also been done to see what types of people tend to benefit most from online self-disclosure. The "social compensation" or "poor-get-richer" hypothesis (Sheldon, 2009) suggests that those who have poor social networks and social anxiety can get more benefit by disclosing themselves freely and creating new relationships through the Internet (Sheldon, 2009). We can see from this that those who may be more introverted are more likely to disclose information on the internet. They find that it is a safe space, and it takes away the factor of having to speak in front of groups of people. However, other research has been done to prove that extraverts are more likely to disclose information online. This brings in the "rich-get-richer" hypothesis (Sheldon, 2009) that states that "the Internet primarily benefits extraverted individuals...[and] online communication...increases the opportunities for extraverted adolescents to make friends... [the research concluded that] extraverted individuals disclosed more online than introverted" (Sheldon, 2009).

Online dating

Some scholars posit that when initiating a romantic relationship, there are important differences between internet dating sites and other spaces, such as the depth and breadth of the self-disclosed information taken place before they go further to one-on-one conversation (Monica, 2007).[37] Studies have shown that in real life, adolescents tend to engage in sexual disclosure according to the level of relationship intimacy, which supports the social penetration model; but in cyberspace, men present a stronger willingness and interest to communicate without regarding the current intimacy status or degree (Yang, Yang & Chiou, 2010).[38] There are also many counter-examples of the theory that exist in romantic relationship development. Some adolescents discuss the most intimate information when they first meet online or have sex without knowing each other thoroughly. Contrary to the path stated by SPT, the relationship would have developed from the core – the highest depth – to the superficial surface of large breadth. In this way, sexual disclosure on the part of adolescents under certain circumstances departs from the perspective of SPT.

Gibbs, Ellison, and Heino conducted a study analyzing self-disclosure in online dating. They found that the desire for an intimate FtF relationship could be a decision factor into how much information one chose to disclose in online dating. This might mean presenting an honest depiction of one’s self online as opposed to a positive one. Having an honest depiction, could turn off a potential date, especially if the depiction is seen as negative. This could be beneficial, however, as it would prevent the formation of a relationship that would likely fail. It could also cause the potential date to self-disclose about themselves in response, adding to the possibility of making a connection.[39]

Some individuals might focus more on having a positive depiction. This might cause them to be more selective in the information they disclose. An individual who presents themselves honestly could argue that disclosing their negative information is necessary as in a long-term relationship, one’s partner would eventually learn of their flaws. An individual who presents themselves positively could argue it is more appropriate to wait until the relationship develops before sharing negative information.[39]

In a separate study, Ellison, Heino, and Gibbs, analyzed specifically how one chose to present themselves in online dating. They found that most individuals thought of themselves as being honest in how they presented themselves and that they could not understand why someone would present themselves dishonestly. To say that most people deliberately deceive people in how they present themselves in online dating is not true. Instead they are presenting an ideal self. An ideal self is what one would like themselves to be as opposed to what they actually are in reality. One could justify this by believing that they could become their ideal self in the future. Some users might present themselves in a way that is not necessarily false, but not fully true either. For example, one could say that they enjoy activities such as scuba diving and hiking, but go several years without partaking in them. This could come across as misleading to a potential date who partakes in these activities regularly. Weight is a common area in which one might present an ideal self as opposed to an honest self. Some users might use older pictures or lie about their weight with the intention of losing it. For some individuals, they might present themselves in a way that is inaccurate but is truly how they see themselves. This is known as "foggy mirror" phenomenon.[40]

Blogging and online chatting

With the advent of Internet, blogs and online chatrooms have appeared all over the globe. There are personal bloggers and professional bloggers – those who write blog posts for a company they work for. Generally, those who blog on a professional level don’t disclose personal information. They only disclose information relative to the company they work for. However, those who blog on a personal level have also made a career out of their blogging – there are many who are making money for sharing their lives with the world.

According to Jih-Hsin Tang, Cheng-Chung Wang, bloggers tend to have significantly different patterns of self-disclosure for different target audiences. The online survey which involved 1027 Taiwanese bloggers examined the depth and breath of what bloggers disclosed to the online audience, best friend and parents as well as nine topics they revealed.[41] Tang and Wang (2012), based on their research study on the relationship between the social penetration theory and blogging, discovered that "bloggers disclose their thoughts, feelings, and experiences to their best friends in the real world the deepest and widest, rather than to their parents and online audiences. Bloggers seem to express their personal interests and experiences in a wide range of topics online to document their lives or to maintain their online social networks." As we can see, blogging is another medium that we can use to understand social penetration theory in today's world. Regarding online chat, research conducted by Dietz-Uhler, Bishop Clark and Howard shows that "once a norm of self-disclosure forms, it is reinforced by statements supportive of self-disclosures but not of non-self disclosures".[42]

See also

References

- Altman, I. & Taylor, D. (1973). Social penetration: The development of interpersonal relationships. New York: Holt.

- Ayres, Joe. (2009). "Uncertainty and social penetration theory expectations about relationship communication: A comparative test". Western Journal of Speech Communication. 43. . 10.1080/10570317909373968.

- West, Richard L.; Turner, Lynn H. (2019). Introducing Communication Theory: Analysis and Application, Sixth Edition. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Education. p. 173. ISBN 978-1-259-87032-3.

- West, Richard (2013). Introducing Communication Theory-Analysis and Application, 5th Edition. McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0073534282.

- Howard, S. (2011). A Primer on Communication and Communicative Disorders. (1st Edition). "a Primer on communication studies, Howard, S. (2001)".

- Sultan, Sarwat; Chaudry, Huma (2008). "Gender-based Differences in the Patterns of Emotional Self-disclosure". Pakistan Journal of Psychological Research. 23: 107–122.

- Jiang, L. Crystal; Bazarova, Natalya N.; Hancock, Jeffrey T. (2013). "From Perception to Behavior: Disclosure Reciprocity and the Intensification of Intimacy in Computer-Mediated Communication". Communication Research. 40: 125–143. doi:10.1177/0093650211405313.

- Infante, D. A., Rancer, A. S., & Womack, D. F. (1997). Building Communication Theory.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- "Changing Minds, Straker, D (2002-2013)".

- Tolstedt, Betsy E.; Stokes, Joseph P. (1984). "Self-disclosure, intimacy and the de-penetration process". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 46: 84–90. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.46.1.84.

- Dunleavy, Katie Neary, and Melanie Booth-Butterfield. “ Idiomatic Communication in the Stages of Coming Together and Falling Apart.” Communication Quarterly, vol. 57, no. 4, 2009, pp. 416–432

- "Social Penetration, Straker, D (2002-2013)".

- Pennington, N. (2008). Will you be my friend: Facebook as a model for the evolution of the social penetration theory. Conference Papers—National Communication Association, 1.

- Cahn, Dudley D. (1984). "Communication in Interpersonal Relationships in Two Cultures: Friendship Formations and Mate Selection in the U.S. and Japan". Communication. 13: 31–37.

- Croucher, Stephen M.; Faulkner, Sandra L.; Oommen, Deepa; Long, Bridget (2010). "Demographic and Religious Differences in the Dimensions of Self-Disclosure Among Hindus and Muslims in India". Journal of Intercultural Communication Research. 39: 29–48. doi:10.1080/17475759.2010.520837.

- Horne, Rebecca M.; Johnson, Matthew D. (2018). "Gender Role Attitudes, Relationship Efficacy, and Self-Disclosure in Intimate Relationship". The Journal of Social Psychology. 158: 37–50. doi:10.1080/00224545.2017.1297288.

- Floyd, K. (2011). Interpersonal Communication (2nd ed.). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Education.

- Griffin, E. A., Ledbetter, A., & Sparks, G. G. (2015). A First Look at Communication Theory (9th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Education.

- Hensley, Wayne E. (1996). "A Theory of the Valenced Other: the Intersection of the Looking-glass-self and Social Penetration". Social Behavior and Personality. 24 (3): 293–308. doi:10.2224/sbp.1996.24.3.293.

- Farber, Barry A. (2003). "Patient Self-Disclosure: A Review of the Research". Journal of Clinical Psychology. 59 (5): 589–600. doi:10.1002/jclp.10161. PMID 12696134.

- Montesi, Jennifer L.; Conner, Bradley T.; Gordon, Elizabeth A.; Fauber, Robert L.; Kim, Kevin H.; Heimberg, Richard G. (2012). "On the Relationship Among Social Anxiety, Intimacy, Sexual Communication, and Sexual Satisfaction in Young Couples". Archives of Sexual Behavior. 42 (1): 81–91. doi:10.1007/s10508-012-9929-3. PMID 22476519.

- Honeycutt, James M. (1986). "A Model of Marital Functioning Based on an Attraction Paradigm and Social-Penetration Dimensions". Journal of Marriage and the Family. 48 (3): 651–659. doi:10.2307/352051. JSTOR 352051.

- Hammer, M. R; Gudykunst, W. B (1987). "The influence of ethnicity and sex on social penetration in close friendships". Journal of Black Studies. 17 (4): 418–437. doi:10.1177/002193478701700403.

- Kim, Jihyun (2016). "Celebrity's Self-disclosure on Twitter and Parasocial Relationships: a Mediating Role of Social Presence". Computers in Human Behavior. 62: 570–577. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2016.03.083.

- Hwang, Jinsoon; Han, Heesup; Kim, Seongseop (2014). "How Can Employees Engage Customers? Application of Social Penetration Theory to the Full-service Restaurant Industry by Gender". International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management. 27 (6): 1117–1134. doi:10.1108/ijchm-03-2014-0154.

- Degges-White, S (2012). "Lesbian Friendships: An Exploration of Lesbian Social Support Networks". Adultspan Journal. 11: 16–26. doi:10.1002/j.2161-0029.2012.00002.x.

- Varjas, Kris; Kiperman, Sarah; Meyers, Joel (2016). "Disclosure Experiences of Urban, Ethnicity Diverse LGBT High School Students: Implications for School Personnel". School Psychology Forum. 10: 78–92.

- Marrs, Sarah A.; Staton, A. Renee (2016). "Negotiating Difficult Decisions: Coming Out versus Passing in the Workplace". Journal of LGBT Issues in Counseling. 10: 40–54. doi:10.1080/15538605.2015.1138097.

- Simonds, L. M., & Spokes, N. (2017). "Therapist self-disclosure and the therapeutic alliance in the treatment of eating problems". Eating Disorders. 25 (2): 151–164. doi:10.1080/10640266.2016.1269557. PMID 28060578.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Sparrevohn, Roslyn M.; Rapee, Ronald M. (2009). "Self-disclosure, emotional expression and intimacy within romantic relationships of people with social phobia". Behaviour Research and Therapy. 47 (12): 1074–1078. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2009.07.016. PMID 19665694.

- Hwang, Jinsoo; Kim, Samuel Seongseop; Hyun, Sunghyup Sean (2013). "The role of server-patron mutual disclosure in the formation of rapport with and revisit intentions of patrons at full-service restaurants: The moderating roles of marital status and educational level". International Journal of Hospitality Management. 33: 64–75. doi:10.1016/j.ijhm.2013.01.006. hdl:10397/20378.

- Tal-Or, Nurit; Hershman-Shitrit, Michal (2015). "Self-Disclosure and the Liking of Participants in Reality TV: Self-Disclosure in Reality TV". Human Communication Research. 41 (2): 245–267. doi:10.1111/hcre.12047.

- Panos, Dionysis (2014). "I on the Web: Social Penetration Theory Revisited". Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences: 185–205. doi:10.5901/mjss.2014.v5n19p185.

- Ledbetter, Andrew M.; Redd, Shawn M. (2016). "Celebrity Credibility on Social Media: A Conditional Process Analysis of Online Self-Disclosure Attitude as a Moderator of Posting Frequency and Parasocial Interaction". Western Journal of Communication. 80 (5): 601–618. doi:10.1080/10570314.2016.1187286.

- McCarthy, A. "Social penetration theory and facebook". Retrieved 22 November 2012.

- Attrill, Alison (2012). "Sharing Only Parts of Me: Selective Categorical Self-Disclosure Across Internet Arenas". International Journal of Internet Science. 7: 55–77.

- Whitty (2008). "Revealing the 'real'me, searching for the 'actual'you: Presentations of self on an internet dating site" (PDF). Computers in Human Behavior. 24 (4): 1707–1723. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2007.07.002.

- Yang, M.L; Yang,C.C; Chiou,W.B (2010). "Differences in Engaging in Sexual Disclosure Between Real Life and Cyberspace Among Adolescents: Social Penetration Model Revisited". Current Psychology. 29 (2): 144–154. doi:10.1007/s12144-010-9078-6.

- Gibbs, Jennifer L.; Ellison, Nicole B.; Heino, Rebecca D. (2006). "Self-Presentation in Online Personals: The Role of Anticipated Future Interaction, Self-Disclosure, and Perceived Success in Internet Dating". Communication Research. 33: 152–177. doi:10.1177/0093650205285368.

- Ellison, Nicole; Heino, Rebecca; Gibbs, Jennifer (2006). "Managing Impressions Online: Self-Presentation Processes in the Online Dating Environment". Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication. 11 (2): 415–441. doi:10.1111/j.1083-6101.2006.00020.x.

- Tang, Jih-Hsin; Cheng-Chung Wang (2012). "Self-Disclosure Among Bloggers: Re-Examination of Social Penetration Theory". Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking. 5. 15 (5): 245–250. doi:10.1089/cyber.2011.0403. PMC 3353741. PMID 22489546.

- B, Dietz-Uhler; Bishop Clark C; Howard E (2005). "Formation of and Adherence to A Self-disclosure Norm in an Online Chat". Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking. 8 (2): 114–120. doi:10.1089/cpb.2005.8.114. PMID 15938650.

Further reading

- Thibaut, J. W. & Kelley, H. H. (1952). The social psychology of groups. New York: John Wiley & Sons.

- Altman, I.; Vinsel, A.; Brown, B. (1981). Dialectic conceptions in social psychology: An application to social penetration and privacy regulation. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology. 14. pp. 107–160. doi:10.1016/s0065-2601(08)60371-8. ISBN 9780120152148.

- Berg, J (1984). "Development of friendship between roommates". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 46 (2): 346–356. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.46.2.346.

- Griffin, Em. (2009). A first look at communication theory. NY, Ny: McGraw-Hill. p. 114.

- Petronio, S. (2002). Boundaries of privacy: Dialectics of disclosure. SUNY Albany.

- Shafer, M. (November 18, 1999). Social penetration theory.

- Taylor, D.; Altman, I. (1975). "Self-disclosure as a function of reward-cost outcomes". Sociometry. 38 (1): 18–31. doi:10.2307/2786231. JSTOR 2786231. PMID 1124400.

- VanLear, C. A. (1987). "The formation of social relationships: A longitudinal study of social penetration". Human Communication Research. 13 (3): 299–322. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2958.1987.tb00107.x.

- VanLear, C. A. (1991). "Testing a cyclical model of communicative openness in relationship development: Two longitudinal studies". Communication Monographs. 58 (4): 337–361. doi:10.1080/03637759109376235.

- Werner, C.; Altman, I.; Brown, B. B. (1992). "A transactional approach to interpersonal relations: Physical environment, social context and temporal qualities". Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 9 (2): 297–323. doi:10.1177/0265407592092008.

- Yum, Y. K.; Hara, K. (2005). "Computer-mediated relationship development: A cross-cultural comparison". Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication. 11 (1): 133–152. doi:10.1111/j.1083-6101.2006.tb00307.x.

- Pennington, N. (2008). "Will You Be My Friend: Facebook as a model for the evolution of the social penetration theory". National Communication Association. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Sheldon, P. (2009). ""I'll poke you. You'll poke me!" Self-disclosure, social attraction, predictability and trust as important predictors of Facebook relationships". Cyberpsychology: Journal of Psychosocial Research on Cyberspace. 3 (2): article 1.

- Paul DiMaggio; Eszter Hargittai; W. Russell Neuman; John P. Robinson (2001). "Social Implications of the Internet" (PDF). Annual Review of Sociology. 27: 307–336. doi:10.1146/annurev.soc.27.1.307.

- Arun Jacob (November 11, 2009). "Social Penetration Theory".

- "Social Penetration Theory". ChangingMinds.org. Retrieved July 3, 2016.

- Chen, Yea-Wen (2012). "Measuring Patterns of Self-Disclosure in Intercultural Relationship". Journal of Intercultural Communication Research. 41 (2): 131–151. doi:10.1080/17475759.2012.670862.